Faith in Doubt

Every Saturday last fall, dozens of men and boys, followers of Rabbi Yitzchak Tuvia Weiss, the aged Chief Rabbi of the ultra-Orthodox organization Edah ha-Hareidis, converged in anger on the Intel factory in Jerusalem to protest that company’s decision to keep production lines open on the Sabbath. The factory lies on a small campus that borders a Haredi, or ultra-orthodox neighborhood, and though etching computer chips is not particularly noisy, its operation was an affront to the devout observance of the day. Intel security ringed the grounds with razor wire, and police set up a perimeter, holding in the protesters who spat and cried, “Nazis! Nazis!” and “You Zionists caused the Holocaust!” Maxine Fassberg, general manager of Intel Israel, announced that if the protests at the factory continued, “the company will be forced to close it and may also decide to leave Israel,” taking with it 6,500 good jobs. That’s what happens, one blogger observed, when you put “Yentl Inside.”

The Jerusalem silicon kerfuffle was just one episode in last autumn’s harvest of religious conflict in Israel. Religious demonstrators showered rocks on cars making use of a city-owned parking lot, recently opened on the Sabbath. In November, a young woman was arrested for wearing a tallit, or prayer shawl, traditionally worn only by men, and carrying a Torah beyond the restricted zone that Israel’s Supreme Court has delegated for non-orthodox prayer at the Western Wall. That weekend, four thousand Israelis rallied in downtown Jerusalem, demanding to “take back the city for secular Jews” and put an end to the coercion of fundamentalist “Ayatollahs.” (My fourteen year old daughter, who herself can sometimes be found wrapped in a prayer shawl cradling a Torah scroll, traveled an hour to be among them.)

Everyday events in Jerusalem constantly force those of us who live in Israel to consider just what is the rightful place of religious convictions, and other strongly held beliefs, in the public square. This is the sort of question that Peter Berger and Anton Zijderveld set out to answer in their brief but ambitious new book, In Praise of Doubt: How to Have Convictions without Becoming a Fanatic. Berger has been an intellectual celebrity among sociologists and others since at least 1967, when he and Thomas Luckmann published an extraordinary book called The Social Construction of Reality. He is also a distinguished Lutheran lay leader. Zijderveld is a Dutch sociologist, philosopher, journalist, and political consultant. As an adviser to his country’s center-right Christian Democratic Appeal party, he insisted that Holland seek to better integrate Muslims, who in turn must seek to become better integrated. He is also an atheist.

Together, Berger and Zijderveld are a potent pair: two supple intellectuals, believer and non-, scarred by the tumultuous half-century over which their scholarly careers have stretched, who have witnessed the death and rebirth of fundamentalist Christianity, Islam, and Judaism in the very different contexts of the United States and Europe. They make a dream team for tackling perhaps the issue in the West today: how can people (and peoples) of diverging beliefs live together peaceably?

Nearly two decades ago, in a famously controversial essay “The Clash of Civilizations,” Samuel Huntington highlighted one of the most important ways in which this issue was taking shape: the rapid growth of a Muslim population in many European nations. In subsequent years, innumerable books have focused on the same situation, often drawing more apocalyptic implications than Huntington did.

In Zijderveld’s Holland, such prophecies gained plausibility when filmmaker Theo van Gogh was murdered by a twenty-six-year-old Moroccan- Dutchman named Mohammed Bouyeri. Bouyeri, who in thoroughly Dutch fashion, rode a bicycle, sidled up to van Gogh on a busy street, shot him several times, and then drew a machete and slit his throat. Afterwards, he placed a note on his victim’s chest, plunging a smaller knife between his ribs to hold it in place. Van Gogh’s offense had been to produce a film about the subjection of Muslim women. Writer Ian Buruma, who grew up in Holland and wrote a book about the murder, found in it “the end of a sweet dream of tolerance and light in the most progressive little enclave of Europe.”

That a grotesque act of intolerance might bring an end to tolerance itself is a conclusion that does not necessarily follow, but it does have a certain logic. Many Dutch citizens—like many citizens of other Western countries—concluded from the murder that Muslims were an unabsorbed and indeed unabsorbable minority. As they saw it, even after years in the most live-and-let-live of Europe’s great cities, Muslims in Amsterdam had soundly rejected this ethos, though it was the very ethos that accounted for the relative peace they themselves enjoyed in Europe.

But what then were Holland, Europe, and the West to do? How could they accept a large minority that rejects the very openness that makes room for such a minority? On the other hand, given their own vaunted commitment to tolerance-uber-alles, how could they not? This paradox of tolerance left many Europeans

convinced that they faced a problem that had no solution.

Not so, write Berger and Zijderveld. The paradox of tolerance is a product of misunderstanding the nature of belief itself, and what it can and should be. We tend to recognize only two sorts of belief, one relativist and one absolutist. In the relativist mode “not only is the religious ‘other’ accorded respect, and conceded freedom to believe and practice in ways different from one’s own, but the ‘other’ world view is … embraced as a harbinger of valid truth.” In the absolutist mode, only one truth is recognized; the believer must either “attempt to impose a creed on everyone” or leave them “to go to hell.”

The meeting of these two sorts of believers is bound to be an unhappy one, Berger and Zijderveld observe, but this is because both modes of belief are dysfunctional in ways that mirror one another: “The danger of relativism to a stable society is an excess of doubt, the danger of fundamentalism is a deficit of doubt.” Planting a shiv in a filmmaker’s chest is a sign of too much certainty, and wringing ones hands about whether or not clerics ought be allowed to fill their congregants with such confidence is a sign of too little.

Both sides would benefit, Berger and Zijderveld write, by finding a “middle ground”, which incorporates a proper measure of “doubt—a basic uncertainty that isn’t prepared to let itself be crushed by belief or unbelief, knowledge or ignorance.” For true believers, a little extra doubt might dilute the righteous certainty that makes it possible to stab directors and fly jets into skyscrapers. For relativists, a doubt of doubt itself—and of the I-say-tomayto-you-say-tomahto approach that an excess of doubt breeds—might make it possible to pull the weeds of fundamentalist hatred before they come to dominate the soil. “Doubt,” Berger and Zijderveld conclude, “is the hallmark of democracy, just as absolute truth (alleged and truly believed) is the hallmark of every type of tyranny.”

Berger and Zijderveld are right, of course. Belief without doubt is cruel and doubt without belief is feeble. They back their assertions with arguments drawn from political, social, and epistemological theory, but one suspects that the source of their perspective is above all their own surpassing Menschlichkeit. For the sort of doubt they call for, and the sort of humility it produces, are above all the crucial active ingredients in basic human decency.

“The meaning of the dignity of humankind comes to be perceived at certain moments of history,” Berger and Zijderveld observe. Once perceived, they continue, the notion that people deserve to be treated with respect and granted autonomy is almost universally “assumed to be intrinsic to human beings always and everywhere.” On this foundation, it is possible to build political, legal, economic, and social institutions that allow people to believe very different things with passion and sincerity, but without the dangerous “quality of certainty.” Taken together, what these institutions look like is liberal, free-market democracy. Michel Foucault once noted that often, while thinking something through, though “sure of having traveled far, one finds that one is looking down on oneself from above.” This is the case for In Praise of Doubt, and in itself this is not an unsatisfactory result. Berger and Zijderveld validate liberal democracy at a time when it seems to need it.

But still, doubt and moderation are virtues with which one cannot take issue, yet they alone cannot achieve what Berger and Zijderveld expect of them. In Praise of Doubt is a book about politics that focuses almost entirely on what people believe and almost not at all on what they do and how they live.

Some years ago, one of the two large dairies in Israel launched a line of yogurt for kids with a dinosaur motif. Everything had dinosaurs. Each flavor had a dinosaur; the print ads showed dinosaurs and the radio spots aired reptilian growls in the background. The Haredi community was quick to complain that this was causing their children to ask troublesome questions about the age of the world. I asked then-Knesset Member Avraham Ravitz, himself a Haredi, how he could be so sure that dinosaurs hadn’t once walked the earth. He laughed and said that he wasn’t sure at all. In fact, he had no problem believing in dinosaurs.

The real problem with the yogurt was threefold. First of all, not all God-fearing parents were religiously sophisticated enough to explain away the apparent contradiction between the prehistoric origins of dinosaurs according to carbon dating and the relative freshness of all creation according to the Torah. This might undermine not only the children’s still-naïve faith, but, even more crucially, their respect for their parents. Finally, even for those who could explain the matter to their children, who wants to have complicated exegetical discussions over breakfast? Who needs the headache? So the Haredim demanded that the dinosaurs disappear, and by the next week there was not a trace of them to be found on supermarket shelves or billboards. But the issue was not belief, and neither was it a dogmatic deficit of doubt. The issue was what gets discussed around the breakfast table.

Something like this is true of the Intel factory. What bothers the zealous Jews screaming epithets is not so much the failure of secular high-tech workers to understand just how much God wants them to keep the Sabbath. It is rather that a factory operating in their own backyard—with cars and trucks coming in and out—prevents them from observing the Sabbath the way they want to observe it. Things more mundane than “belief” are at the heart of the conflict: the noises of lumbering trucks, the freedom to amble down roads with baby carriages, the possibility of escaping all signs of commerce for one day a week. And while Berger and Zijderveld are no doubt right that the righteous anger of the protesters would be nicely tamped if they were more given to humane self-doubt, there is no reason to think that this would resolve the fundamental conflict.

And what’s true in Jerusalem is true elsewhere. Conflict rarely coalesces around belief, emerging instead over behaviors, practices, and policies. Dampening the fires of belief rarely diminishes the sort of conflict Berger and Zijderveld, like the rest of us, find troublesome. Such conflict wanes not so much when people learn to doubt their own cherished beliefs, but when they learn to see beauty and value in the efforts of others to build lives of meaning and purpose and community, even when these lives are far from the ones they might wish to lead. But such appreciation tends not to grow across razor wire, amidst cries of “Nazis!” and “Ayatollahs!” Even in Jerusalem, perhaps especially in Jerusalem, such miracles might be too much to expect.

Suggested Reading

Neither Friend nor Enemy: Israel in the EU

After five years at the European Parliament, the author reflects on Israel's place in the discourse of the EU's chattering (and legislating) class.

Freud as Talmudist

We now understand Sigmund Freud as an anxious Jewish humanist, not the intrepid scientific investigator he thought himself to be. Does that help explain why his interpretations seem so talmudic?

Graven Images

“How do you like my drawing?” Franz Kafka wrote his fiancée Felice Bauer. He took art seriously, and now, finally, we can answer the question ourselves.

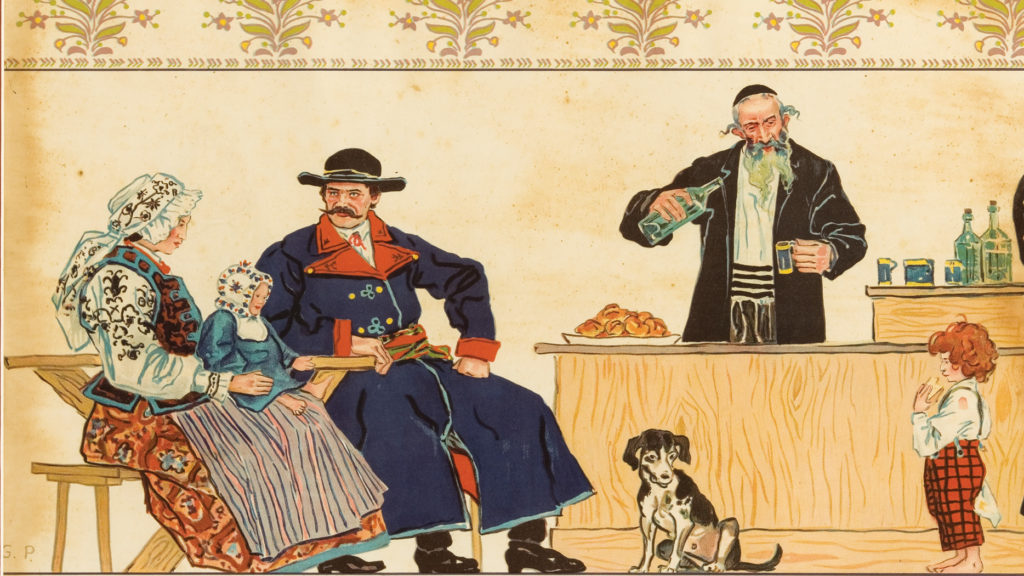

Poland’s Jewish Problem: Vodka?

Jewish-run taverns—rowdy, often very seedy drink-holes—served to cement, rather than sour, the impossibly tense and intertwined lives of Poles and Jews, as a new book by Glenn Dynner shows.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In