Graven Images

“How on earth can I describe how we walked in my dream?” Franz Kafka wrote to his fiancée, Felice Bauer, in 1913. He continues:

When walking arm in arm, the arms touch in only two places, and each person preserves his independence; but as we walked our shoulders also touched, and our arms were in contact all the way down. But wait, I’ll draw it. This is arm in arm: [drawing]. But this is how we walked: [drawing].

How do you like my drawing? I was once a great draftsman, you know, but then I started to take academic drawing lessons with a bad woman painter and ruined my talent. Think of that! But wait, one of these days I’ll send you a few of my old drawings, to give you something to laugh at. These drawings gave me greater satisfaction in those days—it’s years ago—than anything else.

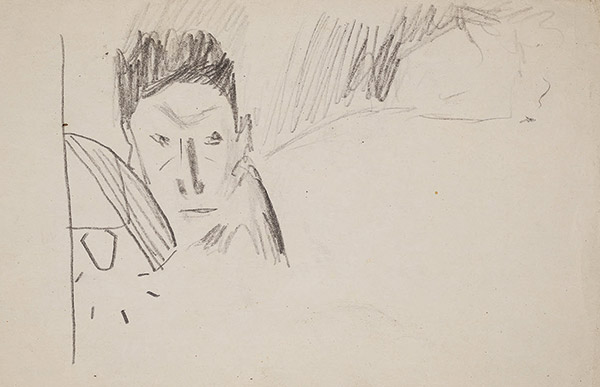

Aware of what writing can and cannot do and of the difference between saying and seeing, Kafka embedded drawings and doodles in the margins of his manuscripts and diaries, in the inside cover of a Hebrew vocabulary notebook, and in letters to the women of his life—including Felice Bauer, Milena Jesenská, and his favorite sister Ottla. He rendered pencil portraits of his mother, Julie; of his cousin Martha Löwy reading; and of his lover, Dora Diamant (sketched on the last page of his last story, “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk”).

Until now, we’ve had only forty of Kafka’s sketches. Even those, because of the sporadic and arbitrary way in which they appeared as occasional appendices to the texts, were seen as mere curiosities. They passed virtually unnoticed by his exegetes (one exception: the brilliant French scholar Jacqueline Sudaka-Bénazéraf). The rest lay dormant and inaccessible for decades in a fifty-two-page sketchbook and nineteen archival folders.

A sensational new book now reveals these hitherto hidden artworks for the first time. It features 150 pages of drawings (some 240 individual illustrations), handsomely reproduced in full color and in their original sizes, together with a catalogue raisonné and admirably researched descriptions by Pavel Schmidt. The book’s editor, Swiss literary scholar Andreas Kilcher, calls this “the last great unknown trove of Kafka’s works.”

The unlikely Kafkaesque story of how Kafka’s drawings have finally been made public, as though retrieved from a geniza almost a century after his death, is worthy of a book in itself (full disclosure: I wrote it). It is the story of a then-unrecognized writer, endowed with genius, whose last wish was betrayed by his closest friend; a wrenching escape from Nazi invaders as the gates of Europe closed; an alleged love affair between exiles stranded in Tel Aviv; and a cultural contest that came to a head in Israel’s Supreme Court.

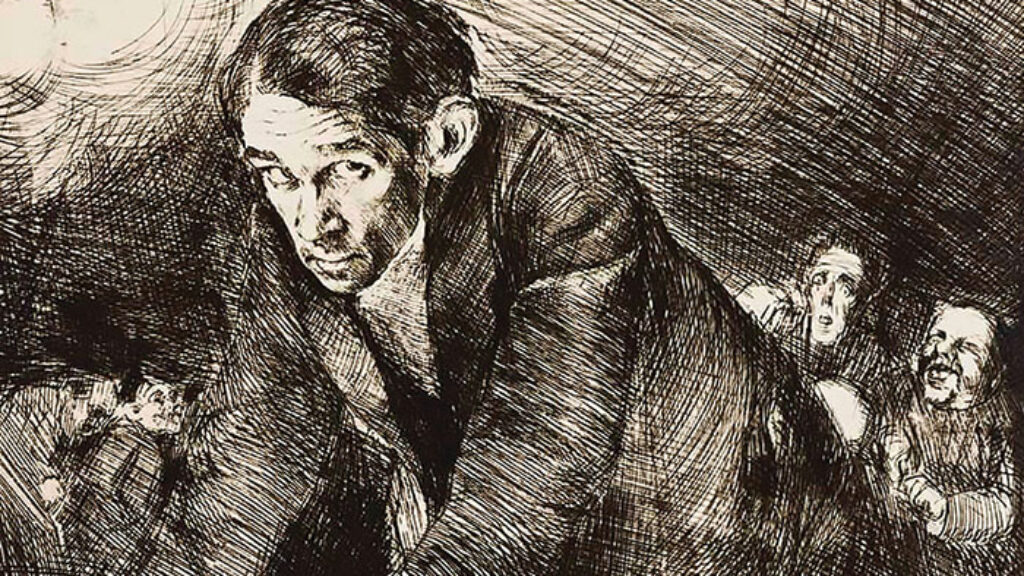

The story begins with the meeting of two law students in Prague in 1902. Max Brod, fascinated by the sketches that Kafka drew in his class notes, asked if he might cut them out and save them. From the beginning, Brod treated Kafka with what he conceded was “fanatical veneration.” “We completed each other,” Brod said, “and had so much to give one another.” They began going to the movies together. In a delightful book called Kafka Goes to the Movies, Hanns Zischler describes what Kafka’s eye absorbed from silent cinema: the poses (or pauses) of suspended movement. Kafka’s novels, Theodor W. Adorno remarked to Walter Benjamin, “are the last, disappearing textual links to silent film.”

Kafka took art seriously. He enrolled in courses in art history, subscribed to art journals, and owned and annotated books by the German Jewish art historian Oscar Bie. He got to know the Austrian artist Alfred Kubin, who would later illustrate Kafka’s short story, “The Country Doctor.” Together with Brod, he visited museums in Prague and Paris. At the Louvre, he skillfully copied a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci and made two virtuoso likenesses of the Borghese Gladiator, a Hellenistic sculpture.

Kafka drew throughout his life, from his law student days at Charles

University to his day job at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute to his

last tuberculosis-stricken months, when he could no longer speak. In his

book Conversations with Kafka, Gustav Janouch reports that more than once he came upon Kafka in the act of

drawing, and each time the writer ripped up the paper. At last Kafka let him

glimpse a page or two. “You really didn’t need to hide them from me,” Janouch

said. “They’re perfectly harmless sketches.” “Oh no!” Kafka replied. “They are

not as harmless as they look. These drawings are the

remains of an old, deep-rooted passion.”

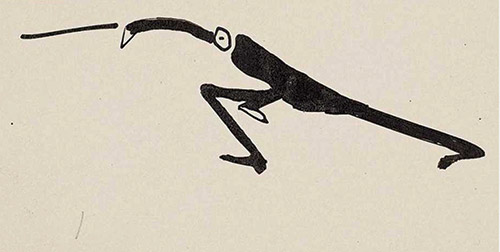

All the while, Kafka tempered that passion with his own version of the biblical prohibition against making graven images. He begged his publisher, Kurt Wolff (to whom Brod had introduced him), never to depict his most famous creation. “The insect itself cannot be depicted,” he cautioned Wolff in a 1915 letter about the cover design of The Metamorphosis. “It cannot even be shown from a distance.”

Neither The Metamorphosis nor his few published stories had afforded Kafka fame, and he hadn’t completed a single novel. Brod would prove as popular and prolific as Kafka was not. His published work would run to almost ninety titles—twenty novels, poetry collections, religious treatises, polemical broadsides, plays, essays, translations, librettos, and biographies.

If Brod obsessively collected anything that Kafka put his hand to, Kafka, in contrast, felt the impulse to shred everything. Brod once described his closest friend as “even more indifferent, or perhaps better, more hostile to his drawings than he was to his literary production. Anything that I didn’t rescue was destroyed. I had him give me his ‘scribblings,’ or I rescued them from the wastebasket.”

At Kafka’s untimely death in 1924, Brod discovered a note in his desk that mentioned the drawings. “Dearest Max, My last request: Everything I leave behind me . . . in the way of diaries, manuscripts, letters (my own and others’), sketches and so on, to be burned unread.”

Rather than obey Kafka’s last message, Brod dedicated himself with singular passion to saving the manuscripts and to rescuing Kafka for posterity. He edited and published Kafka’s three unfinished novels—The Trial, The Castle, and Amerika—and followed these with his selections from Kafka’s diaries, letters, and aphorisms. He published several of Kafka’s sketches in his 1937 biography of Kafka. To the degree that Kafka’s reputation rests on texts he neither completed nor approved, the Kafka we know is a creation of Brod—in fact, his most enduring creation. Knowingly or not, we see Kafka Brodly.

In March 1939, fleeing at the last moment from the Nazi occupation of Prague to Palestine, Brod carried a single cracked-leather suitcase stuffed with loose leaves of Kafka’s manuscripts: journals, travel diaries, sketches, letters, and thin black notebooks in which Kafka had earnestly practiced his Hebrew. Brod left his own manuscripts in a trunk to be shipped later.

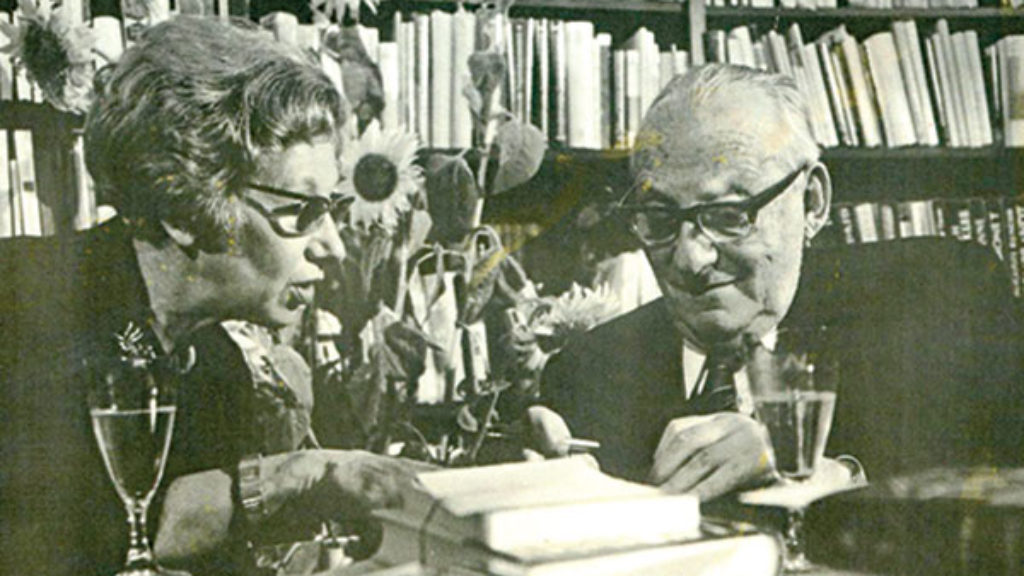

Three years later, Brod met Ilse Hoffe, twenty-two years his junior, a fellow refugee from Prague to Tel Aviv who would serve as his secretary and intimate friend for the next twenty-six years. It was at Brod’s suggestion that Ilse took the Hebrew name Esther, and it was at his urging that she agreed to help him transcribe and organize the papers he had rescued from their hometown. He sensed that she could understand how the manuscripts served as the slackened cord that threaded together his present to the bygone world of his past. Several mornings a week, Esther Hoffe would come to Brod’s apartment in Tel Aviv, a couple of blocks from the beach, to work on Kafka’s manuscripts. Hoffe received no regular salary for her years of work. Instead, Brod gave all his Kafka papers to Esther.

In 1947, in the first of two “gift letters,” Brod explicitly included Kafka’s drawings in his gift to Hoffe. A year later, he mentioned his intention to publish “a large number” of drawings “as a Kafka portfolio.” In 1952, Brod sold two of Kafka’s drawings to the Albertina Museum Vienna. The rest he placed in safe-deposit boxes in Zurich during the Suez Crisis of 1956. From then until his death in 1968, Brod refused repeated requests to publish or exhibit the drawings or even show them to scholars. Did he shield the drawings because he had given them to Hoffe? Because he wished to compensate for his transgression of Kafka’s last instruction? Because he feared that their mysterious singularity would dissipate in a public gallery? He did not say.

When Esther Hoffe died in 2007, the National Library of Israel contested her right to pass them on to her daughters, Eva and Ruth. Esther Hoffe had betrayed Brod’s 1961 will, it claimed, much as Brod had betrayed Kafka’s. In that will, Brod asked that his literary estate be placed, at Esther’s discretion, with “the library of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem [since renamed the National Library of Israel] or the Municipal Library of Tel Aviv or another public archive in this country or abroad.” Since Hoffe had failed to do so, the library argued, Kafka’s manuscripts reverted to the Brod estate, which, in accordance with his will, should be deposited with the library.

During the eight-year trial, the National Library portrayed Kafka as a touchstone of modern Jewish cultural achievement and portrayed Israel itself as the heir of the diaspora’s achievements. As David Blumberg, chair of the board of the National Library, put it: “The library does not intend to give up on cultural assets belonging to the Jewish people.” Eva Hoffe was not persuaded. “Natan Alterman’s archives are in London; Yehuda Amichai’s are in New Haven,” she told me, referring to two of Israel’s most beloved poets. “By what law must a Jewish writer’s archives stay in Israel?”

In summer 2016, the Supreme Court of Israel ruled against her. Eva Hoffe died, heartbroken and destitute, two years later. A month after her death, a team from the National Library was at last granted entry to retrieve manuscripts from the Hoffe apartment on Tel Aviv’s Spinoza Street. In April 2019, a Swiss court recognized the Israeli verdict and granted permission for the manuscripts Brod had deposited in Zurich to be shipped to Jerusalem.

And what treasures did this geniza yield?

The most astonishing revelations in this book include a Chaplinesque figure tripping along with a walking stick; fencers and dancers leaping and lunging from supple lines; acrobats vertiginously balancing on a ladder that rests not on the ground but on the outstretched feet of another acrobat; a figure in Rodin’s classic thinker pose, but twisted into the letter “K”; a desolate man lost in a huge bed, beneath which lingers a pair of slippers; a grimacing drinker leaning over his glass; a man fastened hand and foot to a torture apparatus with four poles (like a scene from Kafka’s most harrowing story, “In the Penal Colony”); a jockey, whip raised, crouched on a tormented racehorse, almost cubist in its rendering; figures seeking admittance to an imposing gate; and a comically flattened self-portrait.

Most are undated and untitled. Occasionally, Kafka supplied captions: “supplicant and distinguished patron,” “bather viewed from the bridge,” “pitiable servants,” “ancient dancer,” “scenes from my life” (on the back of a postcard addressed to Ottla). More often, Brod added the titles: “grotesque couple,” “man at window with curtain,” “junior waiter and chubby-cheeked girl.”

The longer you look at Kafka’s lines, the more calligraphic they look, like

dissolving handwriting or hieroglyphs or leaning letters in an illegible

language. (“Without a doubt,” writes Sudaka-Bénazéraf, “Kafka, linked to

connoisseurs of the Jewish tradition such as Hugo Bergmann, Felix Weltsch and

Max Brod, did not ignore the Zohar’s thesis that God created the world by means

of letters of the alphabet.”) Others are registered in jagged suggestive

strokes: angular, gesticulating stick figures with cartoonishly elongated

limbs, volumeless outlines with nothing underfoot. In his biography of Kafka,

Brod calls these figures “black puppets suspended from invisible threads.” I

prefer to think of them as fanciful depictions of the luftmensch, the

free-

floating, impractical “man of the air.”

Both types are rendered with spontaneity and restless movement that is free of any attempt to reproduce or ratify the real. Both speak a grammar of graphic simplicity—and of parodic humor. Like his stories and parables, Kafka’s drawings are unmistakably his: lean, enigmatic, incomplete, and above all fragmentary, as though they end before they can arrive, or can arrive only at an impasse, at what the Greeks called an aporia. The drawings drive toward that impasse with the same lucidity, the same intensity of utterance, as the texts.

The drawings collected in this book are complemented by an eloquent essay by the celebrity academic Judith Butler, professor of comparative literature at the University of California, Berkeley. Butler’s essay is in itself “performative,” to use a term she popularized, in drawing a line from Kafka’s texts to his drawings. It also rests on hypocrisy, for in referring to and commenting on the material that the National Library has now made freely available, the essay leaves unmentioned the suspicions Butler had expressed a decade ago, as the case wound its way through the courts. Were Israel to gain the contested manuscripts, she said then in the London Review of Books:

Kafka might be instrumentalised to overcome the loss of standing that Israel has suffered by virtue of its ongoing illegal occupation of Palestinian land. . . . If the National Library in Jerusalem wins its case, to have access to the unpublished and unseen materials of Franz Kafka one will have to defy the boycott and will have implicitly to acknowledge the Israeli state’s right to appropriate cultural goods whose high value is assumed to convert contagiously into the high value of Israel itself.

It is to Kafka’s credit that his drawings have now overcome Butler’s qualms—another instance of his posthumous power. More to the point, just as we owe our Kafka to Brod’s disobedience, we owe a debt of gratitude to the National Library for shedding new light on Kafka’s uncanny vision. Taken together, the rediscovered drawings gathered in this valuable volume will allow us to see how, for Kafka, word and image walk arm in arm.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Misreading Kafka

The Kafka myths, and the "myth-busters" who make them.

Kafka at Bedtime

Kafka continues to interest everyone from academics to Hasidic slam poets.

Lost from the Start: Kafka on Spinoza Street

Jerusalem-based writer Benjamin Balint has crafted a wise and eloquent study of Kafka around the eight-year battle in Israeli courts over Max Brod’s literary estate.

And the Heart Is Forever Broken

Amid the ferment of interwar Poland, two opposite motions guided Jews who followed the sometimes blinding torches that lit the way toward modern culture. The first surged outward. The second traveled inward.

gershon hepner

WHY GOD INVENTED LITIGATION

While the most illustrious, very Jewish, author Kafka, surely did not violate

the second of the Sinaitic Ten Commandments God gave Moses,

the preservation of these images which Max Brod, disobeying him, did not annihilate

illustrates “What man proposes and another man opposes”

may often lead to conflicts which don’t seem to be disposed of, and resolved, by God,

whose intervention hardly ever leads to lasting mitigation

of conflicts like the one involving texts and images that Kafka left to Brod,

which is the reason why most sadly God invented litigation.

Ruthie

The drawing captioned "Figure from Kafka’s sketchbook, ca. 1901–1907" in the article appears to me to be quite clearly the Hebrew letter "gimel", anthropomorphized. The text alongside it, "The longer you look at Kafka’s lines, the more calligraphic they look, like dissolving handwriting or hieroglyphs or leaning letters in an illegible language", seems to somewhat strengthen this interpretation. I wonder what text of Kafka's, if any, accompanied this particular graphic and whether others of his drawings can also be seen as being based on Hebrew letters. Just a thought...