Poland’s Jewish Problem: Vodka?

According to a famous Yiddish ditty the Gentile is, to his very core, an alcoholic. By contrast, in the tune’s alternating refrain we “learn” that the Jew is, by definition, genetically sober, studious, and pious:

Shiker iz der Goy (the Goy is drunk)

Shikker iz er (a drunk is he)

Trinken miz er (he must drink)

Vayl er iz a goy (because he’s a Goy)

Nikhter iz der Yid (the Jew is sober)

Nikhter iz er (sober is he)

Lernen (in some versions, Davenen) miz er (he must learn, or pray)

Vayl er iz a Yid (because he is a Jew)

“Shikker iz der Goy” is one of the most popular and least charitable Jewish folk songs of all time. Its stanzas depict the respective hangouts of the Goy and the Yid, namely the tavern and the beit midrash. Its two alternating refrains, “explaining” these polar opposites by way of ethnic, even racial, determinism, reflect long-held and broadly shared biases about the sharply contrasting relationships to alcohol maintained by Gentiles and Jews. The myth of Jewish sobriety was employed by Jews to comfort, flatter, and elevate themselves above the debauched, drunken, and at times violently anti-Semitic Eastern European peasantry. But a far more sinister and predatory version of the fable of Jewish sobriety flourished for centuries among anti-Semites, particularly the temperance-preaching Catholic clergy: It was the Jews’ calculated sobriety that enabled them so effectively to operate a vast monopoly over the lucrative liquor trade by intoxicating and then exploiting innocent and inebriated Christian peasants. These contrasting stereotypes remained widespread, particularly in Poland, for centuries; they persisted through the purported demise of the Jewish liquor monopoly—inaugurated by an array of highly restrictive laws in the 1830s and 1840s aimed at shutting down the ubiquitous Jewish-run taverns. This governmental policy only intensified throughout the Russian Empire—including the so-called Congress Kingdom of Poland—in the 1860s, with the emancipation of the serfs, who, it was hoped, might seriously compete with the Jewish-run liquor business. That never happened.

A mere two decades later, with the Jewish mass flight to America, these same prejudices crossed the Atlantic. The self-comforting myth of Jewish temperance was held by many Jewish immigrants to these shores—more than a few of whom went right back into the liquor businesses of their European forebears, as Marni Davis’ illuminating recent study of the disproportionate role of American Jews during prohibition, Jews and Booze, richly documents. At that time, again paradoxically enough, accusations of the calculated and manipulative sobriety of the Jews inflamed the anti-Semitic rhetoric of the American Christian temperance movement, reaching an ugly apogee during the Prohibition era, when so many Jewish owners of illegal speakeasies and unlicensed taverns, to say nothing of bootleggers, did indeed make their fortunes.

Glenn Dynner’s erudite, meticulously researched, and refreshingly original new book, Yankel’s Tavern: Jews, Liquor, & Life in the Kingdom of Poland, begins by almost entirely demolishing these particular ethnic myths. He ends with a powerful polemic against the modernist biases and misconceptions held by three generations of his academic predecessors regarding 19th-century Polish-Jewish social and economic history, in which the Jewish liquor trade played such a vital role.

Dynner disagrees with the many historians who have tended to accept at face value the exaggerated claims on the part of both legislators in Congress Poland and a tiny elite of Polonized Jews that they had actually succeeded in weaning Jews away from their professional and economic addiction to alcohol by encouraging them to farm, fight for their country, and study in Polish-Jewish academies. He argues that such efforts had almost no lasting impact on the vast majority of Polish Jews. Jewish farmers commonly established drinking holes on their land; Jewish soldiers, upon discharge, could not find more lucrative work than that which the tavern offered; and graduates of so-called rabbinical schools, established by radical Jewish Polonizers, were never taken seriously by either the Orthodox or the Enlightenment intellectuals and thus could find no pulpits to occupy.

Yankel’s Tavern highlights the remarkable resilience of the Jewish saloons that dotted the countryside and the towns of Congress Poland, despite decades of concerted official efforts to shut them down. Indeed, at the very center of Dynner’s book lies the thesis that the Jewish liquor-vending business managed to survive—despite all the legislative and judicial attempts to crush it—thanks to a variety of ingenious ruses devised by aristocratic landowners and their Jewish arendars, or lessees, so many of whom operated lucrative taverns.

Dynner begins his crisp narrative with a vivid portrait of the Jewish-operated “inns,” from late feudal times through the last two decades of the 19th century. His most important finding—supported by painstakingly extensive research in both Polish and Jewish archives—is that Jewish distillers and tavern-keepers served a critically important economic role in Poland, despite the many bans, taxes, and residential restrictions burdening them.

Previous historians have shown that the Polish nobility was as addicted to the Jewish tavern as its patrons were. Dynner, for his part, has demonstrated that this state of affairs continued well into the last quarter of the 19th century. He narrates in great detail how, in the end, the Jews in tandem with the Polish nobles who had for centuries entrusted them (and no one else) with the management of their inns and saloons managed to circumvent all governmental attempts to crush this most lucrative of businesses.

Dynner also devotes much attention to the role played by rabbis in issuing heterei-shutafut, legal fictions that allowed Jews to form partnerships with Gentiles so that their taverns’ activities would not be disrupted by Sabbaths and Jewish holidays. His explanation of the halakhic details of the rabbinical authorizations is, alas, too vague, and in a few instances, plainly wrong. Still, he does make the bottom-line case that scores of rabbis colluded with both the Polish nobility and their Jewish arendars in keeping the taverns open and viable.

Even more originally, in two separate chapters devoted to the complex histories of the Jewish alcohol trade in their very different urban and rural settings, Dynner portrays the Jewish tavern as a unique venue for Polish-Jewish social intermingling, from religious celebrations to lively, and at times dangerously contentious, drunken debates. In doing so, he effectively overturns the commonly held notion that Jewish-tavern keepers were a major source of anti-Jewish resentment on the part of Poles. Unfortunately, in these chapters Dynner tends too often to bombard his readers with eye-glazing, detailed data and scores of statistics that would have more wisely been consigned to his footnotes. Still, his major conclusions represent an important revision not only of popular prejudices and myths regarding this topic, but also of the standard history of the Jewish tavern business in the Russian Empire.

The opening words of “Shikker iz der Goy” are “Geyt der Goy in Shenkl arayn” (the Goy goes into the tavern). Of course, what it conveniently omits is that the Yid was there well before the Gentile, to open shop, ready and willing to ply Polish peasants with his home-made, kosher moonshine. Particularly surprising however is the large number of cases of Jewish alcoholism, which Dynner has gleaned from his major, private, Jewish (as opposed to official Polish) archival source, the more than five thousand petitions, or kvitlekh, presented to the non-Hasidic ba’al shem, Rabbi Elijah Guttmacher, a hitherto untapped resource that he discovered while toiling in the YIVO archives (described by Dynner in “Brief Kvetches: Notes to a 19th-Century Miracle Worker” in the Summer 2014 issue of this magazine).

The Guttmacher archive demonstrates that many Polish Jews not only frequented taverns but themselves imbibed frightening amounts of their brethren’s home brew, leading to widespread abuse that ruined many a Jewish life, marriage, and family. No small number of these petitionary notes to Guttmacher were written by women begging that their husbands stop their chronic drinking, and there are kvitlekh from more than a few men imploring the tzaddik to heal them of their alcoholism. There are also many requests to resolve disputes with the noblemen who owned the property of Jewish tavern-keeps and—most surprising—more than a few requesting a peaceful resolution to intra-Jewish conflicts about the leasing rights and government concessions offered, at times deliberately to raise the stakes, to more than one Jew by the same nobleman or government agent. A few samples give us a sense of Dynner’s rich find:

One Sarah bat Leah appealed to Guttmacher to heal her husband, Moses ben Reizel, of his chronic drunkenness. Moses, she attests is “always drunk, and he comes home and quarrels with his . . . wife. And he does damage and causes [material] losses and she has no rest when he comes home.”

Jonathan ben Feiga Reizel’s drunkenness had brought his household to the brink of starvation, and forced him to pull his children out of school for lack of tuition money. His wife, Liba bat Zela, beseeched Rabbi Guttmacher to “turn his heart so that he will no longer be a drunkard, for it has been several years since he became a drunkard.”

As for the men who visited Guttmacher to cure them of their alcoholism, here are two samples:

Solomon ben Reizel confessed that “he drinks a lot of liquor to the point that it makes him drunk, and because of this he has no domestic tranquility. And may God have mercy upon him and guard him so that he doesn’t drink anymore.”

Eizik ben Rachel, a widower, admitted that he “drinks more liquor than he needs, and then he beats his children, so he asks to give him a cure for this.”

Many petitioners to Guttmacher provide vivid evidence of Gentiles’ attempts to take over the Jewish-run taverns. But, as Dynner observes, “encroachments by fellow Jews occurred just as often, defying our nostalgic image of East European Jewish solidarity (or its anti-Semitic corollary, Jewish collusion).” Among the examples he cites is a long-running feud between the failing (and clearly superstitious) tavern-proprietor Aaron Hayyim ben Feigel and his new, successful competitor just down the road:

Aaron was afraid of Nathan because, he wrote, Nathan “always vexes me—may he not, God forbid, perform any sorcery against me.” For good measure, he slipped in a request for [Guttmacher’s] blessings over lottery ticket numbers 11,766 and 22,763.

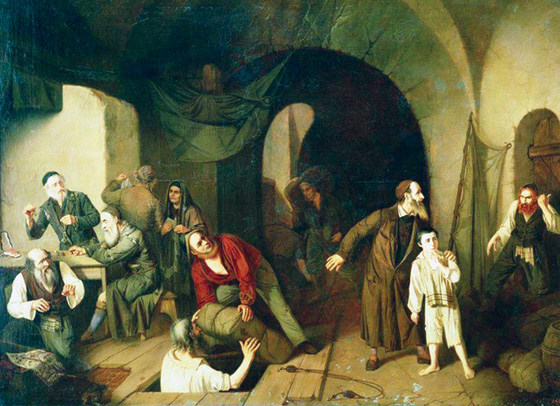

In response to the allegations that the exploitative and manipulative nature of Jewish temperance greatly exacerbated tensions between Poles and Jews, Dynner presents a far more complex, indeed paradoxical, reality. He illustrates how these rowdy, often very seedy drink-holes served to cement, rather than sour, the impossibly tense and intertwined lives of Poles and Jews. Dynner recounts how more than a small number of Polish peasants celebrated their most important life-cycle events, such as weddings and post-baptismal celebrations, at Jewish-run taverns. He offers evidence that a key factor in the success of rural Jewish taverns was the degree of their proximity to the village’s church, ironically observing, in the context of his narrative about two competing Jewish establishments in the Polish countryside, that “One tavern was too far from the local church, which meant that worshippers would not find a place to rest or find shelter during bad weather after services. Another was too close, an affront to the worshippers’ religious sensibilities.”

Of course, what so many Christian worshippers really sought following services was—more than rest and shelter—fun. The taverns’ Jewish proprietors were more than happy to oblige, not only serving booze, but commonly playing the fiddle to their drunken dancing—an image seared into the romantic Polish imagination by Adam Mickiewicz’s classic ballad, Pan Thaddeus, whose righteous Jewish innkeeper and decent musician, Yankel, inspired the title for Dynner’s book.

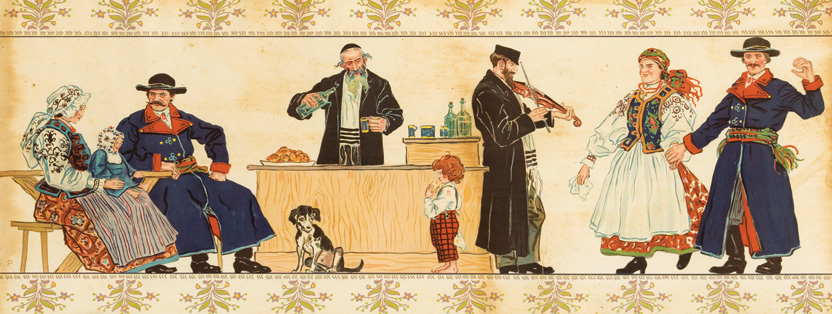

Jews too, we must remember, were regular clients of taverns, especially those that served as overnight roadside resting spots—a chain of kosher, Yiddish Motel 6s—and commingled with their Catholic patrons. After a few drinks, it was far from uncommon for both good-natured joking and animated debates to dominate a late night. The book includes some fine and revealing illustrations from Polish folk art of such commingling, often featuring the Jewish proprietor fiddling while his Catholic customers dance to both Slavic and Yiddish tunes.

There is a widespread prejudice, enduring to this day among many Polish historians, as well as in popular Polish collective memory, that during their two insurrections against tsarist rule (1830 and 1863), Jews constituted a vastly disproportionate number of spies, smugglers, and informants for the tsar and that they accommodated and fed countless Russian soldiers in their taverns. In shattering this myth, Dynner has done remarkably precise accounting, based on official legal records, of the relative number of Jews and Poles convicted, or merely accused, of spying, smuggling, and informing against the insurrectionists, and concludes that, “Surprisingly, such lists contain a sizeable majority of Polish Christian names.” Despite the statistical realities that Dynner has uncovered in the archives, he forlornly, if powerfully, observes: “The suspected Polish Christian spies have been effaced from Polish national history and memory, leaving only a residual memory of accused Jews. If Poland was the ‘Christ among the Nations,’ Jews were supposedly its Judas.”

In fact a surprisingly large number of Jews chose to fight alongside their “fellow Polish” insurrectionists. Moreover, there was strong support for the Polish side in many rabbinical and Hasidic circles. Aside from confirming that the court of the Kotsker Rebbe was a stronghold of staunch support for both Polish insurrections, a matter of common knowledge to this day among both Hasidim and the historians of Hasidism, Dynner cites what he terms “a most extraordinary Hasidic tradition regarding the tzaddik, Samuel Abba of Żychlin”:

And the mouth of our rabbi of blessed memory used to constantly utter that the bringing of the Messiah by our tzaddikim depended on this [Polish restoration]. Because first, the Polish state had to have its autonomy restored as a reward for granting permission to exiled Israel to come and settle in its land, and for receiving [Israel] with open arms . . . after its expulsion from Germany and other lands, . . . and allowing it to raise the banner of Torah and Hasidism, to the extent that all of our rabbinic authorities from the Shulhan arukh and all of our masters of Hasidism emerged from the innards of the Polish state.

This is, without doubt, a powerful assertion, but not nearly as extraordinary as Dynner suggests. After all, Polish-Jewish literature and collective memory are replete with similar salutations, and even sacralizations, of Poland, going back to the 13th-century reign of Bolesław the Pious, who first issued a charter to Jews fleeing violence in the Germanic lands that offered unprecedented legal and religious protection, as well as quasi-autonomy for their kehillot and their courts. The sacralization of Polish cities, towns, and villages reached unprecedented heights with the rise of Hasidism and the intimate association of its rebbes, to this day, with those locales. And yet, despite the long history of profound Jewish gratitude to Poland, and attachment to it, as well as all the new evidence Dynner has uncovered regarding Jewish support for Polish independence, he concludes with wonderment that “it is difficult to explain Jewish motivations for supporting a Polish cause that promised them so little.” I am less surprised.

Radical Jewish Polonizers and, later, modern historians of both Polish and Russian Jewry have maintained that the modernization of the Jews under the rule of Alexander II (1855–1881) effectively put an end to Jewish tavern-keeping by opening to Jews new, “normalized,” and less seedy careers, from fighting Polish insurrectionists to farming Russian land. Dynner contends, in his last and most forcefully argued chapter, that all of the efforts to integrate the Jews—from farming and schooling to soldiering—were, without legal emancipation and economic normalization, doomed. He concludes with a stern cautionary note to today’s historians: “By magnifying a vanguard of Polonized Jews at the expense of the traditionalist majority, we run the risk of writing ourselves into the Polish Jewish past.”

In the end, as Dynner plainly explains, it all came down to the nobility’s perennial fear of change, as well as simple inertia. He wryly observes that “the momentum of traditional practices and beliefs overcame any [modern] nationalist indignations. They [the Polish nobles] preferred to deal with Jews, just as before.” And so he concludes this fine study explaining the capacity of Jewish taverns to re-emerge and re-constitute, indeed reinvent, themselves after every imaginable attempt to crush them with this blunt assessment:

In the end, Jewish tavernkeeping survived because so few of the key players in the liquor trade—nobles, Jews, and peasant customers—could fathom why the state should have been so opposed to it.

And so it was, until the catastrophic events triggered by the Russian pogroms of the 1880s, when the lucrative historical Jewish economic collaboration with the Polish and Russian magnates came crashing down, less like a house of cards than a torrent of whiskey from broken barrels falling off the back of the balegoleh’s wagon.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Forget Remembering

Rutu Modan’s graphic novel The Property explores the uneasy coexistence of love and death.

Religion, Power, and Politics: An Exchange

Rabbi Riskin's review of Rabbi Sack's latest book ignited a discussion on the role of power in Judaism.

My Father, Milton Himmelfarb

Personal reflections on the legacy of a sui generis Jewish American sociographer and essayist.

Wandering Jews

Jews have been travelers since God told Abraham to get up and go. How deeply has this constant motion been imprinted on the Jewish psyche?

gwhepner

SOBER JEWS MUST PRAY OR LEARN

Davenen miz er, the sober Jew must pray,

is what is said in many versions

Of Shikker iz der goy. Another way

some versions read, containing Gershon’s

preference, Lernen miz er, meaning learning

is what the sober Jew must do.

Interestingly, in neither version earning

a livelihood is what a Jew

appears to focus on, since both the davener

and lerner focus with their soul and

heart upon the Aibisher, Governor

to whom the answer while in Poland.

[email protected]

daized79

How does an author, in good conscience, turn Yonasan into Jonathan ben Feiga Reizel and Schlomo into Solomon ben Reizel, call a Polish Jew "bat" anything (Liba bat Zela), and then turn around and keep the name as Eizik ben Rache (not Isaac)? And Samuel Abba? Oy!

As to Poland in the Jewish mind, don't forget po-lin = here we will rest.

I have also read articles on the amount of Yiddish and Hebrew in Polish that seems to have arrived via the criminal class of both (probably in these taverns). The article says the inns were kosher--did they serve kosher meat to the Poles as well? Pricey...

gdynner

How to render Hebrew names was, indeed, a very tough call. I opted for English equivalents whenever possible in order to ease the task of less familiar readers. Yiddish names were kept in the original Yiddish to distinguish them from Hebrew. "Bat" (daughter of) was in the original documents.

-the author