King James: The Harold Bloom Version

Although a self-avowedly compulsive reader, Harold Bloom, our age’s most venerable yet still most provocative literary critic, has more of a writer’s sensibility. Key concepts in his work that are not immediately transparent to most readers of books—”belatedness,” “the anxiety of influence,” literary “contamination,” the “agonistic” relationship of texts—need no explanation for those who write them. Few ambitious authors have not known the discouraging feeling that everything has already been said; that they will never find their own voice; that the voices of other authors they have loved and learned from keep creeping into it. From the fierce and usually secretive competition between a writer and his predecessors, Bloom has fashioned a critical vocabulary.

Even Bloom’s central notion of “strong misreading” has more to do with writing. “Weak misreading,” as he calls it, is common and of little interest; the consequence of inexperience, mental laziness, psychological resistance, or conformity to received opinion, it is what the modernist New Critics with whom the young Bloom studied sought to educate against. Unlike other postmodernists, Bloom has remained loyal to the New Critics’ belief in objectively richer and poorer ways of writing and reading, and in universal criteria of literary evaluation. He made an impassioned plea for these criteria in his The Western Canon; his forsaking of the New Criticism’s methodology of close textual analysis, rather, would seem to have stemmed from his own sense of belatedness. Having arrived on the scene when there seemed little to add to the discussion of strong reading, he turned to strong misreading instead.

Strong misreadings are rare, and occur, according to Bloom, when vigorous and original minds take possession of literary texts or traditions for their own purposes by creatively distorting them, seizing on possibilities of interpretation that ordinary strong readers would reject as implausible. Such forceful appropriations are a new talent’s or generation’s way of clearing a space for itself, an antidote to the anxiety of influence. To resort to a psychological metaphor of which Bloom is fond, the sons become the fathers of their literary progenitors by recasting them in their own image. An example Bloom has given of this is what he takes to be rabbinic Judaism’s strong misreading of the Bible, which robbed it of its primal power while laying a foundation for the grand edifice of rabbinic thought.

Not to be outdone by the rabbis, Bloom, a lifelong admirer of the Bible, aimed for his own strong misreading of it in The Book of J, published in 1990. His point of departure is 19th-century source criticism and its division of the Pentateuch into different strands of authorship known as J (for “Jehovistic”), E (for “Elohistic”), P (for “priestly”), and so on. Bloom proposed a reconstruction of the J-narrative as a literary account of Hebrew origins written by a wittily intellectual woman at King Solomon’s court. Her main protagonist, treated by her with cool irony, is an impulsively masculine God whose “leading quality is not holiness, or justice, or love, or righteousness, but the sheer energy and force of becoming.” That J never meant her Jehovah to be taken as seriously as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam proceeded to do—that the world’s great monotheistic religions were founded on a somewhat whimsical literary fiction—is for Bloom an irony that not even J would have been capable of.

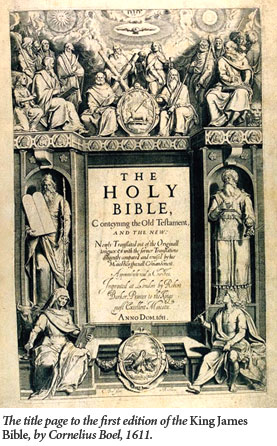

Now, Bloom has returned to the Bible with a book on the King James translation of it, written for the latter’s 400th anniversary. Its title taken from a verse in Isaiah, where it refers to a refuge from the summer sun (for Bloom, it also serves as a metaphor for the Bible’s overwhelming influence on Western civilization), The Shadow of a Great Rock includes an introduction on “the Bible as literature” and chapters on all of its major and some of its minor books, as well as on parts of the New Testament. Each chapter is short and consists of one or more representative passages from the King James followed by a brief commentary. Sometimes these commentaries contain the kind of startling Bloomian aperçus that, casually vaulting over contexts, genres, and historical periods, have the capacity to jolt us into new perspectives. Thus, after quoting the King James rendition of David’s elegy for Jonathan in the first chapter of Samuel II, Bloom continues:

Poet and musician, usurper and anointed monarch, alternately ruthless and expediently compassionate, David anticipates Hamlet as masterpiece of contraries. Like Hamlet, he inspires our love yet does not return it. Hamlet is the hero of Western consciousness and disputes with David the crown of personality, but David is also a religious figure, which may make him even more complex.

David as the counterpart of Hamlet—well, of course! But too often in The Shadow of a Great Rock, Bloom seems merely to be turning the pages of the Bible as quickly as he can, as when, after calling the book of Ruth possibly its “most beautiful work,” he quotes a lengthy passage from the biblical critic Herbert Marks; makes the questionable assertion that “the name Ruth means a ‘friend'” (this is based, as far as I can determine, on his having read somewhere that in the Christian Syriac Bible the name is Re’ut) and the even more dubious claim that Boaz “can be interpreted as ‘strength’ in the particular sense of ‘shrewdness'” (the would-be grasp of Bloom’s Hebrew more than once exceeds its reach in this book); makes a passing reference to Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale”; and concludes with another long quote from a poem by Victor Hugo. This is the purest of paddings for not even the thinnest of garments.

The Shadow of a Great Rock, on the whole, is a disappointment of the sort often caused by occasion-linked books that are written in a hurry under outer rather than inner compulsion. It has a jerrybuilt quality and much of its contents are rehashed from The Book of J. Anyone wishing to read Harold Bloom on the Bible, in fact, would do better to go straight to The Book of J, which is a brilliant if eccentric tour de force. The real shadow in Bloom’s new book is cast by it.

But the problem with The Shadow of a Great Rock goes beyond that and pertains to the King James Bible (KJB) itself. This is because, as a critic, Bloom is preeminently concerned with strong misreadings, which is how he would like to view the King James, too—yet if a translation is the closest possible perusal of a text that there is, the KJB’s must be considered an extremely strong “reading” and not a misreading at all.

Bloom, to be sure, contends otherwise. “The aesthetic experience of rereading the ‘Old Testament’ of the KJB,” he writes in his introduction, “is altogether different from that of . . . the Hebrew text. There is a baroque glory in the KJB and a marvelously expressionistic concision in [the Hebrew Bible]; the contrast is nearly total.” And a few pages further on: “The KJB is an English Protestant polemic against contemporary Catholic and ancient Jew alike. Accept that, and its errors are themselves fascinating.” In both form (its “baroque glory”) and content (its “errors”), Bloom’s argument goes, the KJB, while pretending to be close to the Hebrew original, is a radical departure from it.

This argument, however, which Bloom never pushes very hard or very far, fails to withstand scrutiny, not because it necessarily requires us to regard as duplicitous the KJB’s claim, in its 1611 dedication to King James, to be “more exact” than any previous Bible translation (strong misreadings need not be consciously so), but because there is little to support it. The KJB not only had exactness as its goal (its entire mode of production was geared to it), but managed to achieve it to an impressive extent.

The KJB was produced by committees—six of them all told, of which three, comprising twenty—five members, worked on the Hebrew Bible. All twenty-five were fluent in Latin and many in Greek, and among them were also six competent Hebraists and three Arabists. (The KJB was the first Bible translation to recognize the relevance of other Semitic tongues to an understanding of biblical Hebrew.) Each committee had before it, apart from the Masoretic text and its rabbinic commentaries, the Greek Septuagint, Jerome’s Latin Vulgate, the German Bible of Martin Luther, and the Wycliffe, Tyndale, Coverdale, Bishops’, and Geneva Bibles in English, and each carefully compared them all, frequently borrowing verses from one or the other (especially from Tyndale) or creating pastiches from several. Far from aspiring to a bold originality, the KJB’s translators were cautious and conservative, checking and rechecking their accuracy at every step as befitted men entrusted with God’s word. This is not, as a general rule, how strong misreadings come into being.

Moreover, despite Bloom’s assertion that the KJB, as attested to by its “errors,” is a “Protestant polemic” against ancient Judaism, one would be hard-pressed to point to more than a handful of possible examples, all challengeable. One that Bloom gives is the prophecy of the downfall of the king of Babylon in Chapter 14 of Isaiah, where we read in the King James, “Hell from beneath is moved for thee to meet thee at thy coming . . . How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning!” And Bloom comments: “Hell is a Christian idea; the Hebrew says she’ol, akin to Homeric Dis or Hades, while . . . ‘Lucifer’ in the Hebrew is helel [ben-shachar], the shining morning star Venus.”

Bloom is right that the biblical she’ol denotes a shadowy underworld to which all descend after death rather than a place of future punishment, and that Lucifer is a Christian synonym for the Devil, whereas Isaiah’s helel ben-shachar, probably best translated as “bright son of the dawn,” has no such connotation. This does not add up, however, to a straightforward Christianization of an ancient Jewish text. To begin with, “Hell” and “Lucifer” are far from the King James’ inventions; as far back as John Wycliffe’s 14th-century Bible, the English language’s first, we have “Helle under thee is disturbed for the meeting of thi comyng” and “A! Lucifer, that risidist eerli, hou feldist thou doun fro hevene,” and subsequent English Bibles went along with this. Nor was Wycliffe being original, either. He was drawing on Jerome’s Latin, which has infernus subter conturbatus est in occursum adventus tui and quomodo cacedisti de caelo Lucifer qui mane oriebaris.

Yet Jerome, too, was not a flagrant Christianizer. Although infernus had come by his age to be a Latin noun meaning Hell in the Christian sense, it still retained its older adjectival meaning of “of the underworld,” as when Virgil refers in the Aeneid to a tree at the entrance to Avernus, the Roman Hades, as being Iunoni infernae dictus sacer, “considered sacred to the [goddess] Juno of the underworld.” The Vulgate’s infernus is thus ambiguous, referring either to a place like Hades or to a Christian Hell, rather than an outright mistranslation.

As for Lucifer, ancient Jewish commentators on Isaiah 14 indeed understood helel ben-shachar to be an epithet for the planet Venus, as is already evidenced by the pre-Christian Greek Jewish Septuagint’s Eosphoros, the Morning Star—literally, the “bearer of dawn.” Translating this literally himself, Jerome coined Lucifer from Latin lux, light, and fero, to bear; only later did it become a name for Satan in Christian tradition. Although the KJB’s translators could have chosen to de-Christianize the text by rendering helel ben-shachar as “morning star” (as was done by Luther) and she’ol as “underworld” or (as they actually did several verses further on) “grave,” they can hardly be accused of Christianizing it in the first place. This was simply not their practice, neither here nor elsewhere.

The question of the KJB’s “baroque” style is more complicated, since 17th-century English and 9th-to-2nd-century B.C.E. Hebrew cannot easily be compared. Although it can be maintained that the KJB’s tone is not always that of the Hebrew, whose highly inflected grammatical compactness it could not hope to match, the caveat must be added that, two or three thousand years later, the Hebrew’s precise tone is sometimes difficult to determine. Certainly, the KJB sought to get it right, aiming for simplicity when the Hebrew is simple and majesty when it is majestic. There is nothing “baroque” about “And Abraham rose up early in the morning, and saddled his ass, and took two of his young men with him, and Isaac his son,” while if there is a rhetorical elevation to “Speak ye comfortably to Jerusalem, and cry into her, that her warfare is accomplished, that her iniquity is pardoned: for she hath received of the Lord’s hand double for all her sins,” Isaiah’s Hebrew is rhetorically elevated, too. Are the two passages elevated in exactly the same way? There may be no answer to that (the question itself may be meaningless), but I can’t think of anywhere where the KJB re-orchestrates the music of the Bible to suit an agenda of its own.

At heart, one suspects, Harold Bloom knows all this, which is why The Shadow of a Great Rock has a somewhat perfunctory air. It is a book whose author set out to make a case and understood only when it was too late to turn back that he had none. Bloom is by temperament a strong misreader himself. The Hebrew Bible is a mine of riches for him. The King James version of it, considered solely as the fine and faithful translation that it is, is less so.

Suggested Reading

“I Will Not Speak to Dullards”

“Without leaving the Zoom lecture, I quickly pulled up the YIVO Encyclopedia entry on Leah Horowitz and sent it to my family WhatsApp group: ‘Any chance we’re related?’”

Zionisms Abound

Gil Troy and Allan Arkush on Troy’s new book, The Zionist Ideas.

The Bible’s Women in Medieval Ashkenaz

The Bible’s characters were everywhere in medieval Ashkenaz. Jews remembered them when they prayed, attended births and weddings, when they opened a haggada.

Friendship in the Fields of Moab

Naomi and Ruth have mourned together and are now setting off on the 50-mile journey from the plains of Moab to Bethlehem, toward an uncertain future—alone but side by side.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In