Letters, Winter 2015

With Friends Like These

Those who advocate that Israel should make additional concessions to the Palestinians frequently warn that otherwise, world public opinion, especially in Europe, will turn against the Jewish state. Yet outgoing European Parliament (EP) member Leonidas Donskis, in your Fall 2014 edition (“Neither Friend nor Enemy: Israel in the EU”), presents a portrait of the EP which suggests that there are no Israeli concessions that will ever satisfy European opinion. What Donskis is saying is that, at heart, most members of the European Parliament do not really accept the legitimacy of Israel’s existence. If that is the case, then perhaps the time has come to stop pretending that more Israeli concessions will win Europe’s friendship. Plainly, they will not.

Moshe Phillips

Benyamin Korn

Members of the Board, Religious Zionists of America

New York, NY

Protective Edge

Professor Asa Kasher writes (“The Ethics of Protective Edge,” Fall 2014), “Human shields may be attacked together with the terrorists, but attempts should be made to minimize collateral damage among them, even though those who act willingly are, in fact, accomplices of Hamas. In all such cases, as much compassion as possible under the circumstances must be shown without aborting the mission or raising the risk to Israeli soldiers.”

I must respectfully disagree. Kasher acknowledges that the mission may go forward and that Israeli soldiers are not to be further endangered. But this gets muddled with his asserted obligation to treat willing unarmed military accomplices of Hamas with “compassion.” I believe that this confounds and distorts the moral and legal standing of those who are in effect unarmed combatants with that of “civilians.” The emblematic scene that captures this distinction was from a half-dozen years ago. In it the IDF have cornered a group of Palestinian fighters in a building. In order to aid their escape, a large group of unarmed Palestinian women loudly run in front of the exits of the building, thereby allowing the men inside to hide behind the women and escape. The IDF held its fire. There was no moral or legal requirement to do so.

These were unarmed women dressed in civilian clothes, but those are merely superficial distinctions. The core truth is that they were indeed combatants. If the IDF is correct in refraining from firing on unarmed combatants actively and voluntarily aiding the enemy in combat it is so for political reasons not moral ones.

Lloyd Cohen

Professor of Law, George Mason University School of Law

Arlington, VA

Professor Kasher makes interesting points, but it seems he misses two vital ones. First, the “roof knocking” is hardly a means of limiting civilian casualties in the course of achieving a military goal. That conclusion assumes that the combatants who may (or may not, for that matter) be in the building won’t hear the knock. The practical effect of this tactic and of the bombardment overall is retribution, which, if that was the goal, was successful in that some 44 percent of Gaza has been rendered uninhabitable.

Secondly, I’ve read that the “safe range” for firing in the vicinity of friendly troops is some 250 meters. As New Yorker, I put this in local terms, which means it’s about three city blocks. In an area as densely populated as Gaza, I can’t imagine these weapons can be used in a manner that a) kills combatants and b) limits damage to non-combatants.

Stephan Cotton

via jewishreviewofbooks.com

Asa Kasher Responds:

I thank Professor Cohen for his comment on my article. Two clarifications: First, there is a morally significant difference between “accomplices of Hamas” and certain “human shields.” The former are involved in creating or enhancing danger to Israeli civilians or troops, while the latter stay in the vicinity of terrorists in order to obstruct military activity. While the former may, or even ought, to be attacked as combatants, the latter are not combatants. However, if they are injured or killed in the fighting, their casualties ought not to be described as “collateral damage.”

Second, the women who facilitated the escape of terrorists were accomplices and should have been attacked. Holding fire under such circumstances was wrong: The mission had not been accomplished and the troops were jeopardized. Mission and force protection have priority over a distinction between combatants and accomplices.

Mr. Cotton makes several false assumptions. Military activity during Operation Protective Edge (and previous ones) was not retributive. It was defensive and pre-emptive. Houses were “rendered uninhabitable” only when they served Hamas as sites of production, storage, or launching of rockets over Israel, as well as command and control sites. (The figure of 44 percent of houses having been destroyed is, by the way, a conspicuous fabrication probably gained from some propaganda outlet.)

The “safe range for firing in the vicinity of friendly troops” is irrelevant when you attack a site in which both terrorists and their non-dangerous neighbors are present. Considerations of proportionality do not preclude causing collateral damage in Just War in either theory or practice. Such considerations were made by commanders during Operation Protective Edge and previous ones, as part of the Israeli military ethics I described in my article.

Strange Odyssey

Thank you to Allan Arkush for highlighting Jess Olson’s biography of Nathan Birnbaum and for including mention of the earlier essay by Robert Wistrich on this forgotten figure’s “strange odyssey” (“Zionism’s Forgotten Father,” Fall 2014). Birnbaum’s defection from Political Zionism and his critique of the emptiness of a movement solely rooted in European nationalism is still trenchant. Furthermore, Birnbaum’s embrace of the Agudas Yisroel toward the end of his life only heightens the irony of David Ben-Gurion’s miscalculation regarding Orthodox Judaism’s ability to endure in the Jewish State.

To dismiss Nathan Birnbaum as erratic and unpredictable is to misunderstand his journey, a journey that all Jews face today in the search for Jewish authenticity.

Eli Kavon

via jewishreviewofbooks.com

Cobwebs Cleared

Paul Reitter’s piece on Stefan Zweig (“Like an Elevator,” Fall 2014) was wonderful. For too long Zweig’s actual literary output has been ignored in attempts to make him a representative or exemplar of something that upsets the particular angry critic of the moment. But all those novellas do deserve to be re-read in their beautiful new editions from Pushkin Press and NYRB Classics. With the cobwebs cleared, readers can see these books for what they are: fantastic, compact, and powerfully insightful stories of individual psychology, of ambivalent and conflicting desires empathetically dissected.

Barak Bassman

Ardmore, PA

On Mediocrity and Memory

I “discovered” the Holocaust in 1962 by reading Exodus when I was 12 years old. It had a tremendous effect on me as it sunk in that my family too would have been victims if my grandparents hadn’t immigrated to America. For years I sought out books about the Holocaust—Night, The Painted Bird, and Anne Frank’s diary being among the most memorable—but by 1980 I’d stopped. Maybe becoming a mother had made me too sensitive, but I could no longer bear another description of the death camps, the packed trains, the gas chambers, and the myriad stories of those who’d somehow survived. So I tend to agree with Amy Newman Smith (“Killer Backdrop,” Summer 2014). There are far too many mediocre Holocaust books. Yes, many people found love in the ashes, but Holocaust romance as a genre is obscene. But I can also see Erika Dreifus’ point (“Killer Backdrop: A Response and Rejoinder,” Fall 2014): If authors don’t keep writing Holocaust fiction, the time may come when no one will remember it.

Maggie Anton

via jewishreviewofbooks.com

Suggested Reading

No Greater Love

The Israeli music scene is bringing together world-class Israeli jazz and classic Sephardic liturgical music. Voilà!: the jazz piyyut.

Red Light, Green Light

Shadow Strike by Yaakov Katz, the editor-in-chief of the Jerusalem Post, tells for the first time the full story of the discovery of al-Kibar, the ensuing diplomacy with Washington, and the planning and execution of the Israeli air attack that destroyed the Syrian nuclear reactor.

Poland Is Not Ukraine: A Response to Konstanty Gebert’s “The Ukrainian Question”

Dovid Katz explores what it means to be a “good guy” and a “bad guy” in his response to Konstanty Gebert’s article on Ukraine and its Jews.

Missing Notes

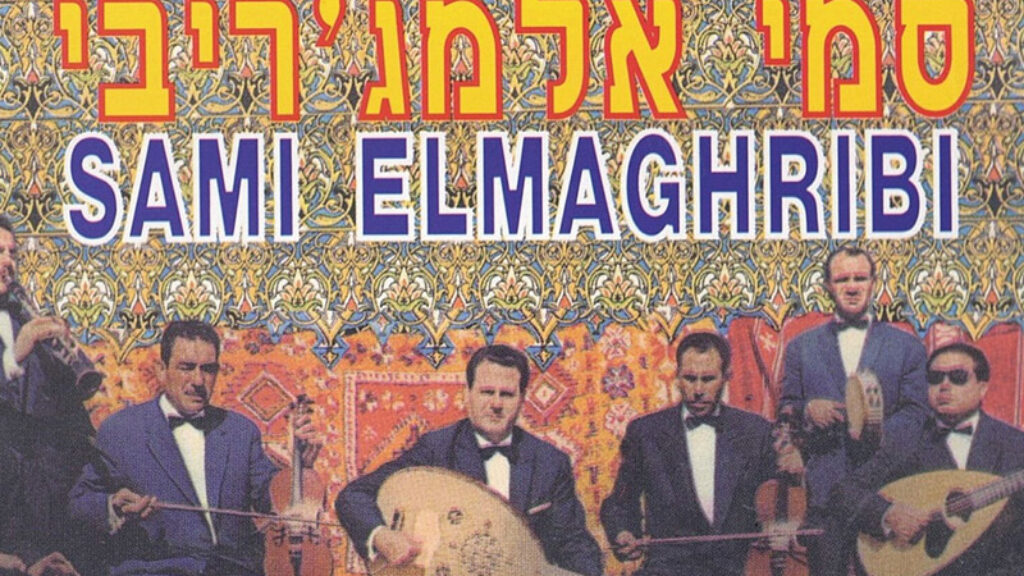

There was a time when Jewish artists set the tone for North African music, but now only echoes remain.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In