Letters, Summer 2015

Otherwise than J

As soon as I started reading Ruth R. Wisse’s review of J: A Novel (“Coming with a Lampoon,” Spring 2015), I put it down to read the novel first. In both Jacobson’s earlier The Finkler Question and Kalooki Nights, as I recall them, there is scant awareness by his characters of Judaism or the Jewish people; in J this state of affairs reaches its apogee as the name of the religion or the people cannot even be uttered, let alone recalled.

I found myself reading from the perspective of an oleh. Jacobson’s world is bleak; the larger world is brutish, unmoored, something less than human. The Js, those to whom “IT HAPPENED, IF IT HAPPENED” are merely reflections of those to whom they themselves are, literally, not.

Frankly, Kevern’s decision not to participate in the renewal of the Js just so they could be annihilated again makes some sense to me. The state of a people whose self-awareness is merely a reflection of others is probably not worth sustaining. The answer, it seems to me, lies in true self-renewal and national renewal, which, of course, is the Zionist project. Jacobson is sardonically funny, internally consistent, and at the end of the day, the frog in increasingly hot water that he allegorizes. That might be the way he wants it, but to me it is a clarion call to be otherwise.

Douglas Altabef

Rosh Pina, Israel

Internalized Guilt

Clearly a major element in the passion motivating Americans to support BDS is the simple frustration of having no realistic alternatives to concretely influence Israeli policies toward the Palestinians (“Climate of Opinion,” Spring 2015). Another element is the internalized guilt people feel about the fact that we ourselves (pretty much no matter where we now call home) are living on lands that were taken from indigenous native populations by means of lies, legal trickery, brutality, and genocidal policies that are historically undeniable. Nothing can be done to change the facts of history, but I suggest that we deal with this guilt by transforming it into righteous indignation aimed at what we perceive (rightly or wrongly) to be similar instances of unfair treatment.

Daniel Liechty

Normal, IL

Alvin H. Rosenfeld Responds:

Most Americans do not, in fact, support boycotts, institutional divestment, or sanctions (BDS) against Israel. Among those who do, many seem driven by passions that far surpass normal criticism of Israeli policies. As Professor Mahmood Mamdani of Columbia University has said “the Palestinian challenge is to persuade the Jewish population of Israel and the world that, just as in South Africa, the long term security of a Jewish homeland in historic Palestine requires the dismantling of the Jewish state . . .Jews can have a homeland in historic Palestine, but not a state.” Needless to say, the overwhelming majority of Israelis and their friends abroad will not be quick to endorse such eliminationist arguments. Nor will they be persuaded by arguments about indigenous peoples: Jews have claimed residence in Israel for a very long time and do not see themselves as alien intruders. Now in its 67th year, Israel is in many ways a strong and thriving country, and most Israelis and their many friends abroad feel no need to apologize for its existence.

Were Arendt and Herzl Wrong About France?

I carefully read and reread Steven Englund’s essay on the Dreyfus affair (“An Affair as We Don’t Know It,” Spring 2015), and, while there is to admire in his review of the new novel about Dreyfus, I felt a sense of letdown by his revisionist thesis. Professor Englund says: “Édouard Drumont, the only important French anti-Semite, was certainly a rhetorical force to be reckoned with at home throughout the years of the Affair, with his incendiary denunciations of the ‘big Jews and their accomplices’ who ought to be court-martialed and executed.”

Has Englund not heard of Maurice Barrès, who, according to Frederick Brown in his important book The Embrace of Unreason, said “That Dreyfus is guilty, I deduce not from the facts themselves, but from his race”? The professor is being led by his revisionist thesis and not by the historical facts when he argues: “But Drumont was a political pariah who was viewed as a corrupt monomaniac. The few dozens of secondary and tertiary French anti-Semites who trailed after him were largely immature adolescents, a handful of failed artists, some police spies, and a plethora of accomplished hucksters and embezzlers. What is remarkable is how this farrago of frauds has mesmerized so many historians who have taken them for what they said they were.”

Were Renoir and Degas minor painters? These two anti-Dreyfussards took out their Jew-hatred on their impressionist colleague Camille Pissarro. From all accounts they made his life miserable with disgusting Jew-baiting. One of the few French painters to side with Dreyfus was Claude Monet. These are not quibbles. It is not Hannah Arendt who was wrong when she argued that the Dreyfus affair was the time when social anti-Semitism in France entered the political sphere, and it was not Theodore Herzl who was wrong when he saw in the Affair the beginning of the end of Jewish life in Europe.

Jacob Arnon

via jewishreviewofbooks.com

Steven Englund Responds:

I thank Mr. Arnon for taking the time to write, and hasten to reassure him I have not only heard of Maurice Barrès, but read Frederick Brown’s book. The pair indeed go together, like Tweedles Dum and Dee. Without Brown, Drumont and Barrès would presently lose the hold they have on received opinion; while Brown, without their articles and books to endlessly reread, would be obliged to look at other sources and think more critically about his evidence.

The point I tried to make in my review is not that Drumont and Barrès are not appalling anti-Semites—this is very old news—but rather that when you put them into perspective by considering the whole of the Dreyfus Affair and what energized it, their importance is far less than is constantly rehearsed in old-fashioned treatments such as Frederick Brown’s.

To repeat: The Dreyfus Affair turned on other matters than just “the Jewish Question,” and French political anti-Semitism was not a major movement even in the Third Republic, let alone in Europe. I cited a good deal of evidence, much of it new, whereas Mr. Arnon’s points are wearily familiar. I strongly urge him to read Grégoire Kauffmann’s biography of Drumont, Laurent Joly’s study of the Action Française, and, above all, Bertrand Joly’s revisiting of the political history of the Dreyfus Affair. If he does so, Mr. Arnon will not come to believe that the France of the belle époque loved Jews (though French Jews very much loved France, as German Jews loved the Kaiserreich, and Austrian Jews adored “der alte Kaiser”), nor that there were no virulent anti-Semites there, as elsewhere. He may, however, come to see that these questions did not drive either the Affair or French history to the degree he has been led to believe.

La Juive

I am grateful for Mitchell Cohen’s wide-ranging article (“Going Under with Klinghoffer,” Spring 2015). However, it missed the valuable opportunity to compare Klinghoffer with the 1835 opera La Juive (The Jewess) by Jacques Fromental Halévy, which had a place in the standard repertoire until the ascent of Nazism a century later. Both operas focus on the predicament of an unjustly accused Jewish protagonist faced with death. In La Juive, Eléazar responds to his sentence by withholding information from his tormentor to achieve symbolic vengeance. For this act Eléazar was often called “the Shylock of Grand Opera,” instead of being granted the status of heroic martyr.

Though biased against Jews in music, Wagner admired the score of La Juive and, in fact, quoted it in his music. One cannot fail to note the parallel opening scenes of Siegfried and La Juive, both beginning with a rhythmic hammering on a smith’s anvil. It is even more ironic that Wagner borrowed a theme from this work to portray the anger of the Nordic war god Wotan, a character who gained new resonance during the Nazi era. One doubts Klinghoffer will become part of the standard repertoire for a century, but it is chilling to think that Jews could still be victimized musically after all that happened since Wagner.

Larry W. Josefovitz

Beachwood, OH

Top Dog

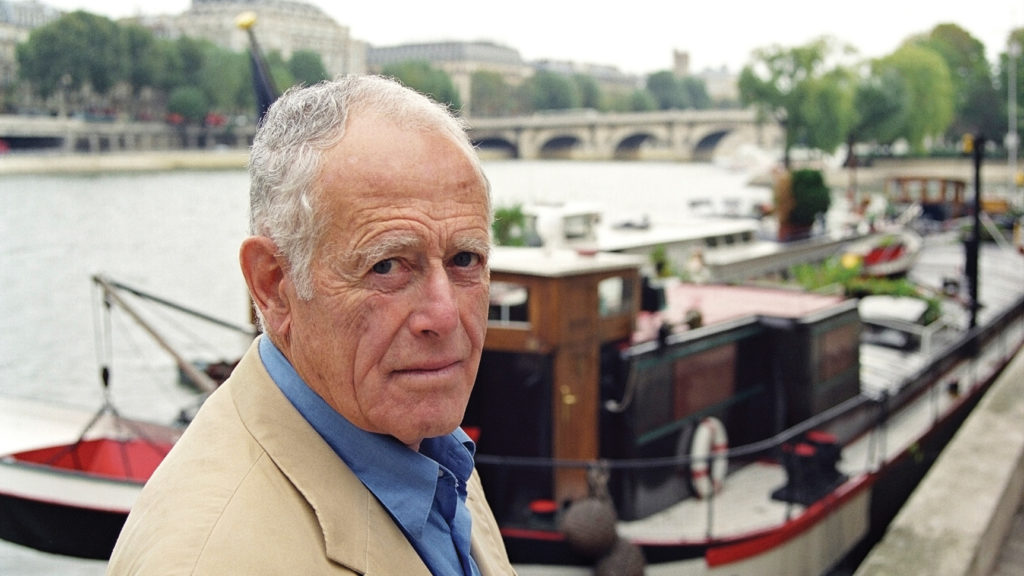

I enjoyed Abraham Socher’s discussion of the latest Saul Bellow books (“Live Wire,” Spring 2015). It took me back to the times when I saw the great man walking to campus with his angled hat and silk foulard. Surely, he would have been glad to know of the continuing high-level attention that is paid him. Still, I wonder. There was a time when novelists seemed central to American culture and the fact that we had the top dog or dogs (Bellow, Roth, Malamud) seemed central to American Jewry. Is either the case anymore?

Tilda Oppenheim

Chicago, IL

Suggested Reading

Torah and the Thermodynamics of Life: An Interview with Jeremy England

Hailed by some as the next Darwin, immortalized as a character in a Dan Brown novel, Jeremy England discusses religion and science, his background, and his intellectual influences.

Love in the Shadow of Death

This is a sad story, one that begins with Sarah Wildman’s discovery among the papers of her grandfather, a physician in Massachusetts, of a file of letters dating back to 1939–1942.

The Hunter

James Salter has been justly celebrated as a composer of gorgeous prose, and his new late-life novel All That Is confirms his reputation as a writer's writer. How much of his artistic vision is predicated on being James Salter rather than James Horowitz?

Disgruntled Ode

For a young daydreamer, nothing is more beautiful than the unspoken, which becomes the focus of desire. And the Jewish unspoken of my childhood was so vast that, within it, the imagination could reach near-spiritual proportions.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In