The Hunter

In my sophomore year of college, I took a class called The Jewish American Novel. I was hoping it would acquaint me with a culture I’d spent much of my youth trying to deny. I grew up in a town in Illinois, where, on the playground, appearing exactly the same as everyone else was a matter of social survival. This was not Jesse Jackson’s Hymietown; this was the United States. We studied the greats in that class, Bellow and Roth, the red-brick Brooklyn of Delmore Schwartz, the Molochs of Allen Ginsberg. Most of the classic types were represented: the worriers and clowns, the big thinkers and survivors. But left out was the sort of Jew that mattered most to me, the Jew who’s trying to pass.

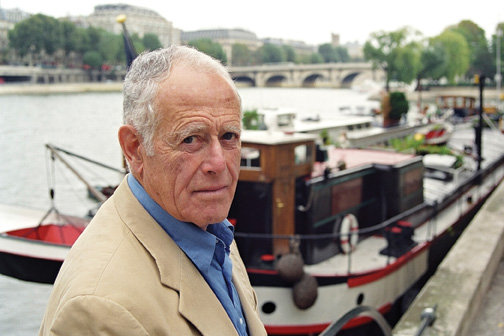

James Salter changed his name from Horowitz for the same reason the Turks renamed Constantinople: He liked it better that way. His career, which began with spare war stories in the mid-1950s, has culminated, just now, with his magnum opus, All That Is, an autumnal novel that caps a stunning body of work. More than any other artist’s, Salter’s career, intentionally or not, has perfectly described the situation of many American Jews, who feel at once free and not free, liberated from Judaism yet stubbornly defined by it. Salter speaks to all those who intermarried and joined the club, donned white bucks and seersucker, who, lost in Sag Harbor and Hilton Head, have spent years trying to slip the shackles as Houdini, né Weiss, slipped his shackles before the multitudes. Between Salter’s most elegant lines, I can still hear Horowitz scream. Neither Bellow nor Roth, it’s Salter—defined by what he’s left out—whose art depicts the Jew who has tried to dissolve the ancient in the American quotidian but still feels a pang of difference.

Life is contingent. In the summer of 1942, James Horowitz, having graduated from Horace Mann in Riverdale, where he was a third stringer on a high school football team that starred Jack Kerouac, was working “on a farm in Connecticut, sleeping on a bare mattress in the stifling attic,” as Salter wrote in his memoir, Burning the Days, killing time until the fall, when he was to enroll at Stanford. Then, a kid who’d been accepted to West Point failed the physical exam, and another kid failed the written exam, opening a spot for the second name on the waiting list: Horowitz. He wanted to continue on to California, but his father, George, had graduated first in his class from West Point in 1918, and, fathers being fathers . . .

It’s instructive to look at Horowitz before he matriculated—“Seventeen, vain, and spoiled by poems, I prepared to enter a remote West Point,” Salter wrote. “I would succeed there, it was hoped, as [my father] had”—as you would not be seeing that young man again.

He went in shaggy; he came out sheared. He went in dreamy; he came out steely, realistic, remorseless, and fascinated by machines. What do they do to a plebe at the Academy? They line him up, shout him down, run him, humiliate him, punish and break him, burning away the eccentricities that make him unique. Horowitz resisted for a time, turning up, each Friday, for a synagogue service conducted by a local rabbi. Whereas church services were part of the schedule, attending Friday night meant separating yourself from the group, coming back alone, not wanting to explain. “After an hour of services, eternal and unconnected to the harsh life we were leading, we marched back to barracks where everyone was studying or preparing for the next morning’s inspection,” Salter wrote much later. “I felt uncomfortable about having been gone. Though no one ever said a word, I felt, in a way, untrue. In the end I dropped out and went to chapel with the Corps.”

In short, they broke him, then remade him in the image of the rest. The Jewish thing was driven inside, where it remains in hiding, occasionally spilling out between the lines. “Of course, you cannot drop out—you may perhaps try—and I became part of neither one group nor the other, but it seemed to me that God was God, as the writings themselves said, and what essentially distinguished me was an ingrained culture, ages deep, which in any case I wanted to put aside.”

This quote is interesting for what it says, but also for when: It was written many years after the fact, in a memoir published in 1997. Salter had obscured his background for much of his career. So here was a man in his 70s grappling, not with “all that is” but with all that had been put aside. Even so, you still hear the words—the truth of the biography—catch in his throat. He’s like an old le Carré spy who still can’t break cover even decades after the game ended.

Though it was years before he took the pen name, Horowitz became Salter at West Point. That’s where he assumed a new identity, a military cast of mind, learned to love neat hierarchies and the importance of rank. From his first publication, he’s been obsessed by physical trials, feats of endurance, heroic acts. Critics attribute it to the influence of Hemingway, but it really comes from the Academy: It’s the ideology that filled the vacuum when he switched from Friday night to Sunday morning, because “[t]he most urgent thing was to somehow fit in, to become unnoticed, the same.”

In 1944, Horowitz was sent to Pine Bluff, Arkansas for Army Air Corps flight training; he would eventually become a pilot in the Air Force, then in its golden age. By 1950, he was a flyboy out of Tom Wolfe, buzz cut in the cockpit, screaming over Europe. The military supplied him with material, history, and myth, a lore that predated him and would continue long after he was gone. Salter’s work is crowded with vainglory: immortal, imperishable, unconquerable.

Looking back, after a distinguished lifetime of avoidance, he wrote:

We were [stationed] not far from Dachau, the ash-pit. One of them. I had seen its flat ruins. That Otto Frank, Anne Frank’s father, had served as an officer in the German army in the First World War, I may not have known, but I was aware that patriotism and devotion had not saved him or others. They might not save me, though I swore to myself they would. I knew I was different, if nothing else marked by my name. I acted always from two necessities; the first was to be like everyone, and the second—was it foolish?—was to be better than other men. If I was to be despised I wanted it to be by inferiors.

In 1952, he volunteered for a fighter wing and was sent to Korea, which was then at war. For several months, he operated at the tip of the spear, flying jets above the frozen 38th parallel, waste places and factories, the Yalu curving toward the Yellow Sea. It gave him a real-world credibility that would eventually make him an oddball in the literary world, where no one does anything but go to parties, read, and write. He led squadrons, flew as a wingman, tumbling through the sky, chasing the Russian MiGs that howled from the north. He made a study of “aces,” pilots in possession of the mysterious thing. But there still was a sliver of the old poem-saturated Horowitz, dreaming of the perfect phrase.

His first novel, The Hunters, was a story of American pilots in Korea. He’d written it at night, in a notebook (stashed, one is tempted to say, beside his Judaism). Fly all day; report all night. The book appeared under the name James Salter in 1956. He later described the pseudonym as a necessary precaution. “It was essential not to be identified and jeopardize a career—I had heard the sarcastic references to ‘God Is My Copilot’ Scott. I wanted to be admired but not known.” He claimed he chose Salter because it “was as distant as possible from my own name.” But it seems no mistake that he chose an old Anglo-Saxon name, a Christian name first used to identify musicians who played the psaltery, a medieval harp. He’s always had a taste for pedigree. “A name is a destiny,” he wrote. “It is the first of all poems. Even after death it keeps its power; even half-buried in newsprint or dirt, something catches the eye.”

Salter suffered from a disease diagnosed by the early Zionists, for whom a Jewish nation—what if Horowitz had been flying a Mirage over Sinai instead of an F-86 over the Yalu?—was the cure. Simply put, Salter believed what they told him at West Point—about the world and about himself. He internalized it, then shaped himself around this conception. If he wanted to be a great pilot and a great American writer, he could not do it named Horowitz. It’s the same mentality that turned Bernard Schwartz into Tony Curtis. And it’s the reason why, for many of us, the famous first line of Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March—“I am an American, Chicago born . . . ”—is so liberating.

Perhaps surprisingly, this internal conflict does not weaken Salter as a writer but deepens and complicates him. In this, he is akin to Isaac Babel, the great writer of the Russian revolution, a Jew who rode with the Cossacks in the war between the Reds and the Whites. It’s the telegraphic prose style as well as the dilemmas buried deep but still visible. Here’s another Jew riding through the goyishe countryside, dressed like a soldier. In one of Babel’s famous stories, “My First Goose,” the narrator, a bespectacled intellectual, finally earns the respect of his comrades by slaughtering a destitute family’s goose.

I caught up with it and bent it down to the ground; the goose’s head cracked under my boot, cracked and overflowed. The white neck was spread out in the dung, and the wings began to move above the slaughtered bird . . . ‘The lad will do all right with us,’ one of [the Cossacks] said, referring to me, winking and scooping up some cabbage soup in his spoon.

For Salter, initiation came in the air, riding the wing of a laconic hotshot.

Never looking at me, absorbed by the instruments in front of him and by something in his thoughts, sometimes watching the world of dark forest that swept beneath us, hills and frozen lakes, he was gauging my desire to belong. It was a baptism. This silent angel was to bring me to the place where, wet and subdued, I would be made one with the rest . . . Afterwards he said not a word to me. The emissary does not stoop to banter. He performs his duty, gathers his things, and is gone. But the snowy fields pouring past beneath us, the terror, the feeling of being for a moment a true pilot—these things remained.

One should note the term baptism: a new name, a new faith. And you sit and eat the goose with the Cossacks.

Then there’s the point of view: For Babel, it was from horseback, an unusual position for a Jew. It’s about freedom and movement as much as perspective. “An orange sun is rolling across the sky like a severed head,” writes Babel. “[A] gentle radiance glows in the ravines of the thunderclouds and the standards of the sunset float above our heads. The odour of yesterday’s blood and of slain horses drips into the evening coolness.” For Salter, writing only a few years later, it’s not horseback but the cockpit of a jet fighter at thirty thousand feet, a point of view once reserved for God: “We crossed Gibraltar, like a pebble far below, and then brown, hard Spain. We were going home with new airplanes, the first of those that could routinely fly faster than the speed of sound.”

The Hunters was a hit. It sold and sold. It was purchased by Hollywood, where it was turned into a film starring Robert Mitchum. Just like that, a new road opened before Salter. He had been career military, on the Pentagon path. He would forsake all that, go the Hemingway, which was Paris and publication parties and off-season resorts. He made the decision at thirty-two. No matter what else you might think of Salter, you have to acknowledge his bravery: To give up a career of rank and insignia for literature takes guts. He later wrote about wandering the Pentagon, in uniform, looking for someone who would accept his resignation. Then he went home and cried. When he told a friend what he had done, the friend said, “You idiot!”

In the mid-1960s, he began working on the book that would become his artistic breakthrough. It was like nothing he’d ever done: a chronicle of an affair, a young American and a French girl, their story narrated by a third-party voyeur. Everything is in retrospect, years later, a strange run of towns and restaurants, escapades in bed.

Over the crown of western hills we sail beneath a brilliant sky of clouds shot through with sunlight and began the descent to town . . . And then those great, lineal runs through neighborhoods I knew nothing of, making straight for the perfect square which marked the city like a signet.

His writing had matured, clipped and beautiful but also a threat. It gets in your head and comes out your mouth. The odd comma, the odd beat: “September. It seems these luminous days will never end. The city, which was almost empty during August, now is filling up again. It is being replenished. The restaurants are all reopening, the shops.”

Salter is obsessed with light—it pours down, fills up, lingers. After light, darkness. After life, death. In this way, his books are about nothing and about everything. A Sport and a Pastime can be read allegorically. It’s boy meets girl, but it’s also the writer fantasizing about a world he can never truly possess, not the Paris of hotel lobbies but the impenetrable towns of bourgeois France. It’s a fever dream, a poem of unrequited love. Critics heard an echo of Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Henry Miller. Americans abroad, enraptured by foreign places. To me, it’s less Hemingway than Herzl—with his Christmas tree and fantasy of seamless assimilation. Salter is Herzl before Dreyfus, or whatever made him a Zionist, grasping at a mirage, always going but never arriving, always outside, humping through the exile. If you wear just the right coat, strike just the right pose, assume just the right name . . .

“They drive through the streets of an unknown town,” he writes in A Sport and a Pastime.

The rain pours down like gravel. In the green light of the instrument panel he feels as homeless, as desolate as a criminal. Gently she wipes his wet cheeks with her fingers. They have nowhere to go. They are strangers here, the doors of the town are closed to them. Suddenly he is filled with intimations of being found somehow, of being seized and taken away. He doesn’t even have a chance to talk to her. They are separated. They are lost to each other. He tries to cry out in this coalescing dream, to tell her where she should go, what she should do, but it’s too complicated. He cannot. She is gone.

The manuscript was rejected by his publisher. It was such a departure. And it was boring. And it was about nothing. And it was pornographic. It was then turned down by just about every other publishing house in New York, until it was finally put out by George Plimpton and The Paris Review. The ensuing trajectory of the novel describes the arc dreamed of by every author whose book has tanked: Three hundred copies sold the first year, three thousand sold the second, ten thousand the third, and so on. In 1995, it was republished by the Modern Library, a rare honor. It’s now rightly considered a classic.

Salter is often said to be a writer’s writer. He’s more like a writer’s writer’s writer, unread by the public. Yet he goes on, page by page, a man with a message he knows will prevail in the end. He followed A Sport and A Pastime with Light Years, which many consider his greatest novel. He was living in New City, a suburb on the Hudson a few dozen miles above Manhattan. The novel tells the story of a seemingly perfect marriage as it comes apart. It’s about meals, cities, people, habits, worldviews, but its real subject is time, which does not exist and is also the only thing that matters. People age before your eyes, collapse like old houses, give up the ghost before they die. The book is a perfect example of the Salter aesthetic: The taut sentences and icy scenes are organized to spotlight Salter’s brilliant prose and, perhaps also, to disguise Horowitz. I wouldn’t keep harping on this if he didn’t try so hard to disguise it. Of all the Jewish writers of his generation, Salter might be most influenced by his Jewishness.

Somewhere, in just about every Salter book, you’ll find a seemingly anti-Semitic passage. It’s not just what he says, but the way his narrators seem to regard Jews: less as individuals than as instances of a type. In Light Years, it comes at the beginning, when introducing a main character, who was based on a friend and neighbor of Salter:

He was a Jew, the most elegant Jew, the most romantic, a hint of weariness in his features, the intelligent features everyone envied, his hair dry, his clothes oddly threadbare—that is it say, not overly cared for, a button missing, the edge of a cuff stained, his breath faintly bad like the breath of an uncle who is no longer well. He was small. He had soft hands, and no sense of money, almost none at all. He was an albino in that, a freak. A Jew without money is like a dog without teeth.

In the new novel, it comes near the end, when the protagonist finds himself among Jews:

As he sat there, Bowman was more and more conscious of not being one of them, of being an outsider. They were a people, they somehow recognized and understood one another, even as strangers. They carried it in their blood, a thing you could not know. They had written the Bible with all that had sprung from it, Christianity, the first saints, yet there was something about them that drew hatred and made them reviled, their ancient rituals perhaps, their knowledge of money, their respect for justice—they were always in need of it. The unimaginable killing in Europe had gone through them like a scythe—God abandoned them—but in America they were never harmed.

Why does Salter do it? It’s a question I’ve often considered—because I love his books, the best of which cast a spell that lasts for days. I’ve come up with three possible reasons. The first is that Salter always wanted to write his version of the great modern novel in the manner of Hemingway and Fitzgerald, whose books were riddled with the kind, country club anti-Semitism that went out of fashion after World War II. In emulating the old models, he’s taken the bad with the good, the movable feast but also the prejudice that gives the whole thing its neat tone of exclusion. It reminds me of a kid who copied a friend’s homework. In the middle of the page, without realizing what he was doing, he wrote, “continued on the back.” But perhaps that lets him off too easy, because Salter really does seem to harbor a variety of the anti-Semitism that suffused the army’s officer corps before World War II. To be Jewish is to be venal, weak, and grasping, and he is the poet of a certain kind of glorious American masculinity. Or maybe it’s just a diversion, meant to demonstrate that he’s not really Jewish. I mean, what Jew would write, “A Jew without money is like a dog without teeth.”

Whatever its source, such artifice and obfuscation can make Salter’s work, at its weakest, seem phony, a fancied depiction of a world that exists only in the minds of a small community of East Coast WASPs. In this mode, Salter most resembles Ralph Lauren, another name-changing Jew who internalized the lie and the fantasy. Like Lauren, né Lifshitz, Salter has drawn on an invented past to place himself at the center of an impenetrable world that is impenetrable only because it doesn’t exist. It’s a snipe hunt. It’s a joke. A guy told a guy who told a guy, and there you are, holding a burlap sack open in the forest and cooing like a dove. The result, in Salter’s case, is an art that is sometimes false. No one laughs in his books; no one wrestles, curses, or sweats. It’s a picture window in New Canaan where everything is just a little too perfect.

Salter’s new novel, All That Is, published when he was eighty-seven, is a masterpiece, a singular work that restates his entire oeuvre. He’s been working on it forever—his first novel in thirty years. The book is about what it feels like to be alive, captured through the life of Philip Bowman, a New York book editor whose story takes us from World War II to the day before yesterday. It’s beautiful and terrifying: beautiful because Salter can write like the wind, terrifying because it’s a life without rules or a code, where the only deities are human, the only immortality by daring act. God is gone, his place taken by roads a moment before sundown, love affairs, betrayals, hotels, beach grass, and houses by the sea (there are no oceans in Salter; just seas).

At Salter’s age, one expects an artist to reconcile his written and his actual self. With All That Is, it’s clear this will not happen. Salter will never make room in his work for Horowitz. It is, in fact, the distance between that gives his work its candied, marzipan power. His novels capture the slipperiness of the world, where there’s no telling where reality ends and artifice begins. It’s the sensation you have when you see a beautiful girl vanish down a mysterious street in a foreign county, where the trolley cars clatter and the muezzins call the faithful as the bulls race between the high walls—a sensation that lasts right up to the moment when you actually chase down and talk to that girl.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Great Family Circle

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, “the father of modern Hebrew,” famously raised his own son to be the first child in almost 2,000 years to speak only Hebrew. When Itamar Ben-Avi grew up, he was fascinated by . . . Esperanto. Esther Schor’s new book on L. L. Zamenhof, his would-be universal language, and those who still speak it inspired Stuart Schoffman to revisit the oddly parallel careers of Ben-Yehuda and Zamenhof.

Sundowning

In Morningstar Heights, Joshua Henkin tells his story simply and directly, with a narrative economy that conceals much close observation and human understanding. These have always been the strengths of his work, though they are not the qualities best rewarded in contemporary American fiction.

In Brief, Spring 2012

Baseball, Beats, and Scandals in Satmar.

Not Just Hummus

Exploring Israel's culinary culture with two new, very different books about cooking. Jerusalem expats Yotam Ottolenghi and Sami Tamimi have put out a cookbook with remarkable fusions and creations inspired by the holy city, while Abbie Rosner explores the biblical cuisine of the Galilee.

farbsom

"Whatever its source, such artifice and obfuscation can make Salter’s work, at its weakest, seem phony, a fancied depiction of a world that exists only in the minds of a small community of East Coast WASPs. In this mode, Salter most resembles Ralph Lauren, another name-changing Jew who internalized the lie and the fantasy. Like Lauren, né Lifshitz, ..." Rich Cohen, beautifully captures my view of James Salter the novelist. While some of his paragraphs seem tantalizing the whole isn't.

Cohen's use of analogto to Isaac Babel is less convincing. Babel was a great artist and he didn't hide his Jewishness not even from the Cossacks. As a convinced Bolshevik, like Trotsky, he believed that antisemitism was a bourgeois phenomenon not applicable to Lenin's Russia. God were they wrong. I love Babel's art his short stories have what James Salter said of an Italian woman in "Burning the Days," (his only readable book) the "ring of truth."

jvandenburgh

Part of the greatness of both Isaac Babel and James Salter is their ability to be both of their time and yet transcend it and so create both a palpable sense of the era in which their characters are alive (with, yes, societal prejudices intact) and the language with which to speak this truth to future generations.

What those who accuse Salter of anti-Semitism ask is that he'd have made a better world than than this one is, a Rodney King one resembling some cornball Christian heaven where everyone simply gets along.

To judge James Salter on the basis, solely, of how good a Jew he is sounds strangely like what Hunter S. Thompson said about the boring-ness of baseball: A bunch of Jews arguing on a porch.

This isn't literary criticism, rather -- like the "feminist" critics who have accused Salter of thought crimes against women because of the actions of his characters -- it's extra to the work itself.

If you're a close reader of Salter, as I am (and I'm also a close reader of Babel) you find his positioning his characters to the side of any and all groups, including the most basic group, which is the heterosexual couple, in which these often tragic characters are trying to find respite from an existential loneliness.

I suggest everyone re-read the magnificent story "American Express,' which is about two men, lawyers, sons of lawyers (and Jewish) and money and woman and power and morality. It culminates in this astonishing line: "They were like thieves."

Morality in every great writer is complicated because that's how it is in real life.

farbsom

"What those who accuse Salter of anti-Semitism ask is that he'd have made a better world than than this one is..."

I don't know who Jvandenburgh has in mind, and I don't know what kind of question he is asking. For my part, I don't think of Salter as a great writer (his antisemitism has nothing to do with it. Dostoevsky was an antisemite and a great writer nonetheless. On the other hand Isaac Babel was a great writer no matter what one thinks of his private life. I usually don't bring up a writer's prejudices. In this case it is legitimate because I am responding to the reviewers assertion that Salter's antisemitism made him a great writer. I took issue with this strange and unproven view. Bringing up "ike the "feminist" critics who have accused Salter of thought crimes against women..." Doesn't prove anything except show that the letter writer needs to take refuge in irrelevant and trite comparisons.

litchick13

Superb review, thanks.

Sari Friedman

www.Sari-Friedman.com