Minhag America

This “short history” of the synagogue in America is concise, fairly comprehensive, and the first of its kind. Marc Lee Raphael, a distinguished historian of American Judaism, has not only made use of much of the standard scholarly literature but has rummaged through countless boxes of materials of the kind seldom studied with care: synagogue bulletins, governing board minutes, and rabbis’ sermons in 125 locations throughout the United States. San Francisco, Omaha, and St. Louis get their due along with the more frequently discussed synagogues of Brooklyn, Savannah, Philadelphia, and other major cities. Raphael’s gracefully written book draws on all of these sources to offer a remarkably compact synoptic story, one that contributes a great deal to a full accounting of the American synagogue. (Some readers will regret the absence of footnotes in a work of such abundant scholarship.)

Other institutions have arisen over the years to make strong claims on this country’s Jews. For example, from the late 19th century through the early decades of the 20th century, landsmanshaften, or hometown fraternal organizations, built communal relationships among Eastern European immigrant men, and often their families. These organizations filled their members’ lives with meetings and activities, as well as serving as mutual aid societies. But like many other ethnic organizations, they rarely attracted a third, or even a second, generation.

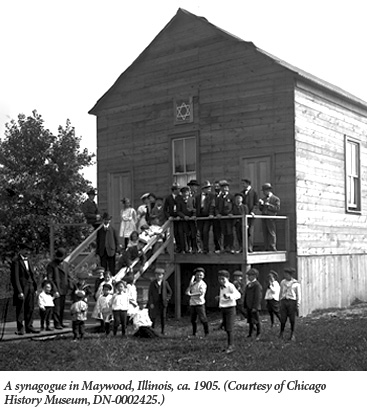

Yet synagogues continue to flourish. They have proven to be flexible—some would argue entirely too flexible—institutions that respond to, and on occasion, lead cultural, religious, and generational change. Still, as Raphael emphasizes more than once—but does not make it his aim to explain—synagogues have never succeeded in attracting the majority of American Jews.

By the early days of the Republic, there were already six synagogues in the United States. They were all Sephardic in their ritual and organization, as Raphael points out, even though the majority of their members were Ashkenazim, primarily from Germany. It was not until the 1820s that groups of Ashkenazim broke away from the established synagogues and started new ones in which their own communal customs would be maintained. Before long, however, many of these very customs fell victim—in the veteran synagogues as well as the ones created by 19th-century immigrants—to the passion for reform or reforming that gripped American Jewry.

This took place even within those synagogues that remained Orthodox. From the end of the 18th century onward, in all American synagogues, there was, for instance, a new concern with “decorum.” The Hungarian-born rabbi Bernard Illowy, who served in synagogues from New York to New Orleans, and who was aptly called “a valiant champion of Orthodoxy,” is reported to have aspired to “a decorous and beautiful service . . . that could more than vie with that of any Temple in the land,” and repeatedly railed against the “indecorous scramble and rush to get out” of the synagogue “before the last echoes of the [closing hymns] had died away.” On occasion, the issue of decorum even rose to the level of constitutional importance. “The 1851 constitution of the newly formed Emanu-El of San Francisco, in Article IV, Section 3 (with its articles and sections, like so many others, it imitated the structure of the U.S. Constitution), required the trustees to ‘promote order and decorum during divine service.'”

This took place even within those synagogues that remained Orthodox. From the end of the 18th century onward, in all American synagogues, there was, for instance, a new concern with “decorum.” The Hungarian-born rabbi Bernard Illowy, who served in synagogues from New York to New Orleans, and who was aptly called “a valiant champion of Orthodoxy,” is reported to have aspired to “a decorous and beautiful service . . . that could more than vie with that of any Temple in the land,” and repeatedly railed against the “indecorous scramble and rush to get out” of the synagogue “before the last echoes of the [closing hymns] had died away.” On occasion, the issue of decorum even rose to the level of constitutional importance. “The 1851 constitution of the newly formed Emanu-El of San Francisco, in Article IV, Section 3 (with its articles and sections, like so many others, it imitated the structure of the U.S. Constitution), required the trustees to ‘promote order and decorum during divine service.'”

Why decorum should have become a matter of such great concern is a question upon which Raphael does not reflect at length, but notes only that it may have been “spurred on by the protestantization of American Judaism” or been “just a general response” to the aesthetics of 19th-century culture. Perhaps he regards this issue, like the question of women’s place in the synagogue, as one that would necessitate historical and cultural interpretation of the kind for which there is no room in “a short history.” The reader, however, regrets the absence of a deeper engagement with the meaning of acculturation for Jews in this period, since what was really at stake both with respect to decorum and to gender was the question of how Jews shaped their culture to fit the norms and behavior of white, Christian Americans.

Proceeding at very different speeds, most of the mid-19th-century synagogues were on a trajectory pointing toward “Reform Judaism.” But when could they be said to have arrived there? “The rabbi and historian Leon Jick has suggested that ‘worship with uncovered head’ was the ‘hallmark of Reform,'” Raphael observes, “but dozens of UAHC congregations still required men to wear hats in 1879.” In 1894, a Reform rabbi was so thoroughly committed to the Americanization of his Chicago synagogue that he not only tossed out its ark, but also gave the Torah scroll to the University of Chicago Semitic Library, never planning to read from it again. Raphael has a striking, even disturbing, number of such anecdotes. His own criterion takes a cue from the historian Marsha L. Rozenblit, and highlights the moment when a congregation abandoned the traditional, fixed liturgy in favor of a truncated new prayerbook as the “mark of a full-fledged Reform congregation.”

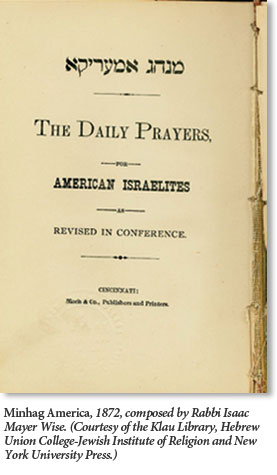

The 19th-century Reform leader Isaac Mayer Wise named his prayerbook Minhag America because he aspired to construct a liturgy that would serve as the “custom” of all American Jews. But by the beginning of the 20th century, the arrival in the country of masses of Eastern European Jews, who were anything but Reform-minded, had clearly obviated the possibility of such an outcome. Solomon Schechter, who came to America with the hope of fortifying a Conservative Judaism that would serve as the umbrella for all synagogues and Jews not officially represented by the Reform movement—his “Catholic Israel”—saw his hopes dashed too. Up until the Great Depression, Jews continued to build synagogues where rabbis promoted visions for the Jewish future that were distinguished by greatly different orientations toward matters ranging from the language of prayer to prayerbooks to Zionism.

The 19th-century Reform leader Isaac Mayer Wise named his prayerbook Minhag America because he aspired to construct a liturgy that would serve as the “custom” of all American Jews. But by the beginning of the 20th century, the arrival in the country of masses of Eastern European Jews, who were anything but Reform-minded, had clearly obviated the possibility of such an outcome. Solomon Schechter, who came to America with the hope of fortifying a Conservative Judaism that would serve as the umbrella for all synagogues and Jews not officially represented by the Reform movement—his “Catholic Israel”—saw his hopes dashed too. Up until the Great Depression, Jews continued to build synagogues where rabbis promoted visions for the Jewish future that were distinguished by greatly different orientations toward matters ranging from the language of prayer to prayerbooks to Zionism.

Raphael passes over the period of World War II rather quickly, noting only that “nearly everywhere, congregational bulletins and trustees’ minutes have little to say” about the war. The important political activities in which Jews were engaged during the war, he correctly observes, “were largely organized outside the synagogues of America.” But his narrative slows down when he comes to the postwar period, marked by the mass movement of urban Jews to what he calls “the real suburbs”—not marginally exurban zones but “newly developing areas, beyond city borders, that were reachable mainly by train and automobile.”

This migration (and not only of Jews) was due, Raphael provocatively argues, to the movement of “blacks into previously white neighborhoods.” And where the Jews went, the synagogues soon followed. With the notable exceptions of synagogues in Chicago’s Hyde Park, and Philadelphia, urban Reform temples and Conservative synagogues were transplanted to new suburban locales, where they constituted the core of their movements’ unprecedented growth. How ironic it was, then, that the dominant theme of Reform rabbinic Friday night sermonizing during this period, including that of some Southern rabbis, was civil rights and racial injustice.

At the same time, the rabbis of the Conservative movement, whose synagogues were the more common choice of religiously affiliated suburbanites during the first postwar decades, devoted their sermons to more specifically Jewish themes, utilizing more traditional Jewish texts. While a count of the people that postwar Reform rabbis quoted most often included “Matthew Arnold, Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Martin Luther King, and Hasidic rabbis,” Conservative rabbis were more likely to call upon the Talmud and Maimonides, as well as Martin Buber, Zacharias Frankel, and Franz Rosenzweig. But, on the whole, neither Reform nor Conservative rabbis preached, except on the High Holy Days, to more than a small percentage of their congregants.

At the same time, the rabbis of the Conservative movement, whose synagogues were the more common choice of religiously affiliated suburbanites during the first postwar decades, devoted their sermons to more specifically Jewish themes, utilizing more traditional Jewish texts. While a count of the people that postwar Reform rabbis quoted most often included “Matthew Arnold, Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Martin Luther King, and Hasidic rabbis,” Conservative rabbis were more likely to call upon the Talmud and Maimonides, as well as Martin Buber, Zacharias Frankel, and Franz Rosenzweig. But, on the whole, neither Reform nor Conservative rabbis preached, except on the High Holy Days, to more than a small percentage of their congregants.

The Orthodox had this problem too. Interestingly enough, Raphael can tell us little about what took place in their synagogues at this time, largely because few of them bequeathed to posterity anything remotely resembling an archive. But we do have the transcripts of many sermons, and they often show us rabbis who chastised “their congregants for lax synagogue attendance and lax observance—what Rabbi Simon Dolgin in Los Angeles called ‘indifference to Judaism’.” Those congregants who did show up were often asked to grapple with difficult rabbinic sources (“did very many of the congregants understand?—doubtful.”)

In his final chapter, “Reinventing, Experimenting, and Ratcheting Up,” Raphael brings the story of the American synagogue up to the present. His brief overview of the past four decades covers dramatic transformations, including the integration of women in unprecedented ways across the movements, the increasing acceptance of gays, and a dramatic shift away from “decorum” that focused on informality in prayer services. He also examines the redrawing of the denominational map, the growth of Reconstructionism, a remarkable resurgence in Orthodoxy, and the decline of denominationalism.

Given the breadth and brevity of Raphael’s survey of the most recent developments, there are inevitable omissions. Too little attention is paid to forces such as Lubavitch Hasidism and Aish HaTorah that are crucial for an understanding of this era. Raphael also overlooks Mechon Hadar, whose support for a halakhic, egalitarian, non-denominational Judaism has played a critical role in the recent development of independent minyanim. This organization’s commitment to training leaders of these groups suggests that it is developing a vision, if not a movement, that aims to provide an alternative to denominational synagogues.

Given the breadth and brevity of Raphael’s survey of the most recent developments, there are inevitable omissions. Too little attention is paid to forces such as Lubavitch Hasidism and Aish HaTorah that are crucial for an understanding of this era. Raphael also overlooks Mechon Hadar, whose support for a halakhic, egalitarian, non-denominational Judaism has played a critical role in the recent development of independent minyanim. This organization’s commitment to training leaders of these groups suggests that it is developing a vision, if not a movement, that aims to provide an alternative to denominational synagogues.

These omissions notwithstanding, The Synagogue in America offers a readable and concise history of the evolution of American Judaism in its synagogues, drawing on sources that allow a panoramic view. Raphael shows in detail how the nation’s religious pluralism has inevitably led to the development of the multiple Judaisms practiced within a wide range of synagogues. That 21st-century American synagogues have reformulated conceptions of decorum, prayerbooks, and theology, not to mention the meaning of acculturation, only underlines how dramatically these Judaisms are changing.

Suggested Reading

The End of Europe as We Know It?

Why does Europe, the late 20th century’s greatest success story, now look so chaotic?

Heart Work

As a successful young novelist, my father had literary friends who now included Angus Wilson, Frederic Raphael, John Wain, and Isaac Bashevis Singer. All came to tea in my nursery. Stanley Moss, my godfather, went on to make a fortune from art dealing.

Inerrant or Oblique?

John Barton has written a wonderful book about the Bible for believers and nonbelievers alike.

The Peculiar History of the Etrog

How an obscure Chinese fruit became a centerpiece of Sukkot and a symbol of Judaism.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In