Harlem on His Mind

There is nothing quite like a controversial exhibition to draw a crowd, generate headlines, and foment anxiety. Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968, the ambitious blockbuster of a show mounted by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1969, accomplished all that—and then some. Ask any curator which exhibition has stood the test of time as a touchstone of cultural politics, a cautionary tale of what can go wrong, and the answer, invariably, is Harlem on My Mind.

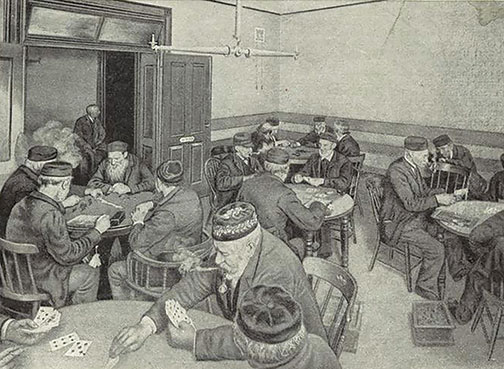

Intended to “create an awareness that didn’t exist,” the exhibition drew on the latest technological innovations to bring Harlem to life. Seven hundred images of its residents going about their daily business, culled from the file cabinets of James Van Der Zee, a longtime Harlem photographer, were projected at a fast clip; an equal number of large-scale photographic murals—today de rigueur, back then an arresting novelty—hung on the walls. To heighten the effect of what Allon Schoener, the show’s curator, described as “electronic theater,” music was piped into the galleries, creating a “dynamic, pulsating environment.”

Harlem on My Mind did more than pulsate. It rocked, throwing the art world for a loop, disturbing New York’s Jews, alienating and angering many segments of the African-American community, and upsetting the city’s equilibrium, especially along Fifth Avenue where dueling constituencies—the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, the Jewish Defense League, and the John Birch Society, among them—stood their ground and protested. Art critics damned the exhibition for having politicized the mighty Met and for mistaking sociology for art, the Jews cried foul at the anti-Semitic tone of one of the catalog essays, while African Americans derided the enterprise from start to finish as the equivalent of an “urban plantation” and as a “staggering display of honky chutzpah.” Within a few months’ time, Harlem was on everyone’s mind.

Although the exhibition did not figure in Jeffrey S. Gurock’s first book, When Harlem Was Jewish, 1870–1930, which was published in 1979, or in the dissertation that midwifed it, I suspect that it was also on his mind. How could it not? When it came to thinking about that uptown neighborhood, about issues of transition and of cultural ownership, Harlem on My Mind raised the stakes. Gurock’s book raised them even higher. Consider its title. I suppose you could argue that it was intended as a descriptive, even literal, account of the story that unfolded within its pages: Once upon a time, long before it emerged as the “cultural capital of Black America,” Harlem was a Jewish neighborhood, through and through. But When Harlem Was Jewish strikes me now, as it had when I first encountered it, as a rebuke, perhaps even as a gesture of defiance, against those who had written the Jews out of Harlem’s history. Gurock puts the Jews on the scene as early as the post-Civil War era, credits them with having developed much of the neighborhood’s building stock, and maintains that by the early 20th century the uptown enclave rivalled the Lower East Side, its downtown counterpart, in its density, collective Jewish identity, and historic import. Harlem, he tells us, was the “second largest concentration of East European immigrants in the United States.”

Since the publication of When Harlem Was Jewish, the field of American-Jewish history has come into its own. Urban history, too, has matured, as have the associated fields of urban planning, American studies, and African-American studies. In his new book, Gurock returns, or, as he likes to put it, “revisits” the urban ghetto of Harlem. The author, who teaches at Yeshiva University in uptown Manhattan, has read widely; he is familiar with, and mindful of, most of the latest studies and their preoccupations, but they are not what propel him. What animates his book is the oldest of historical motives: the imperative to remember. As the journalist and urban chronicler David W. Dunlap observed in 2002 in the New York Times, “On the map of the Jewish diaspora, Harlem is Atlantis . . . It is as if Jewish Harlem sank 70 years ago beneath the waves of memory, beyond recall.”

Gurock’s account is not only a valentine to Jewish Harlem and a celebration of what its author calls its “transcendent significance”; it is also a buoy. Taking his cue from Dunlap, Gurock is determined to keep Harlem’s Jewish history from oblivion. This concern fueled the pages of his first book, too, where he proudly noted that When Harlem Was Jewish “constitute[s] the first major effort to accord a measure of historical recognition to an until-now forgotten community’s history.” At the time that volume was published, there was still a fighting chance that visual clues to the neighborhood’s Jewish past might endure. In the 1970s and 1980s, walking tours of “Jewish Harlem” remained a going concern, a popular Sunday morning pursuit. There was what to see: here and there, Stars of David, the Ten Commandments, and a cornerstone marked 5668. Since then, vestiges of the Jewish presence have grown scant. As gentrification proceeds apace and Harlem increasingly becomes the destination of well-heeled and white New Yorkers, many of the churches that had once been synagogues have now been torn down to make way for apartment buildings with all the latest amenities.

Saddened and alarmed by this recent turn of events, Gurock seeks to set the record straight once again lest a new generation of readers forgets anew. Harlem, he writes, “kept its shelf life and is now worthy of appraisal because what started among its Jews in the streets and institutions uptown did not stay in the neighborhood . . . Harlem’s Jewish story speaks to the past and present and augurs to presage the future of American Jews.” A second justification for taking another look at Harlem’s Jewish history is the “wealth of new knowledge,” the availability of new sources made possible by digitization. A third is the prospect that the neighborhood might once again be home to a community of Jewish residents. The book’s subtitle, its Introduction, and its penultimate chapter, with their explicit references to “revival” and “renewal,” say as much. “I write about Harlem and its Jews, certain that a new generation of readers, beginning with those who have once again moved ‘uptown,’ desires to know…how Jewish Harlem rose,” Gurock explains.

Whatever its motivations, The Jews of Harlem does not so much reframe as amplify. It expands the contents, not the theoretical landscape, of the earlier work. Gurock sticks to the script, but goes deeper. His first book, riding on the crest of the academy’s (blessedly short-lived) fascination with quantitative methods, was awash in charts, graphs, and tables. His latest one is oriented around anecdote. Details, not metrics, enliven the text.

Many of the stories it tells reflect a more inclusive approach toward the past, featuring an enlarged cast of characters, institutions, and historical phenomena. Sephardi Jews, absent from the narrative the first time around, now figure more prominently, as do rent strikes, kosher meat strikes, and bakers’ strikes, as well as shul politics galore. Gurock vividly chronicles the ways in which tradition ran aground on newly acquired notions of taste and decorum. He writes of a committee of laymen who, finding the rabbi’s sermons too “boring,” insisted the clergyman “simplify” them, lest those in the pews continue to “rush to the door like from a fire,” when he spoke. In another telling instance, a Harlem synagogue decided to charge an admission fee for Sabbath morning services. When word got out of an ensuing melee between those who had tickets and those who had none, the congregation was publicly upbraided. “The menorah over the entrance of the synagogue [should] be renamed and the Sign of the Dollar over the broken tablets of the Ten Commandments be substituted,” chided the Hebrew Standard, an influential Jewish newspaper. The Jews of Harlem also pays close attention to the increasingly fraught relationship between African Americans and American Jews, setting it in within the aisles of Blumstein’s department store on 125th Street and the projectionist’s booth at the Lafayette Theatre on 132nd Street and Seventh Avenue. And, yes, several pages are given over to a discussion of Harlem on My Mind.

What stays with you long after you have finished this book is Gurock’s steadfast devotion to his subject. Not too many of us have either the opportunity or the inclination to turn things over and over again. We would do well to follow his example.

Suggested Reading

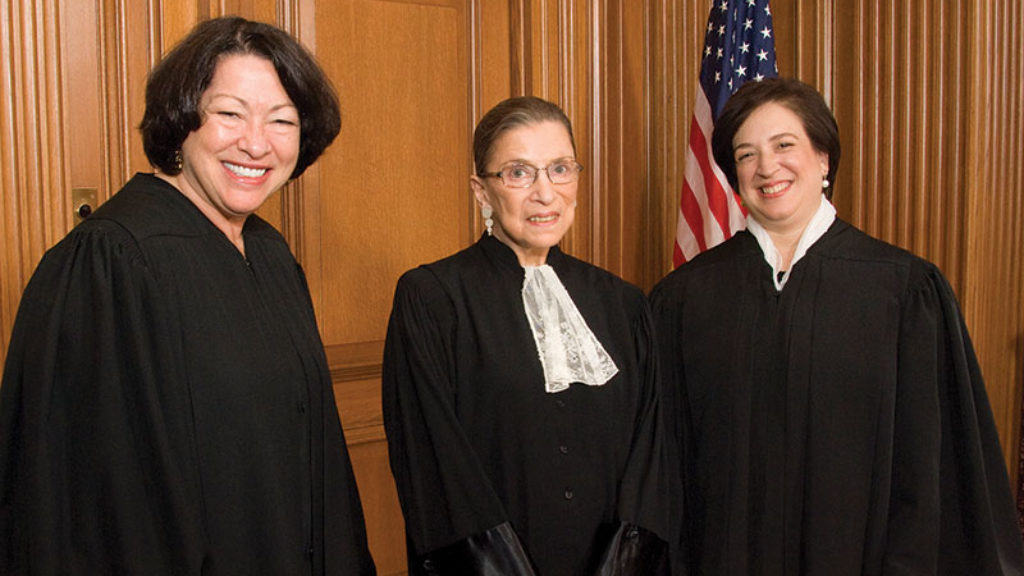

Great Jews in Robes

If Merrick Garland had been successfully confirmed for the seat now occupied by Neil Gorsuch, Jews would have been just one vote shy of constituting a majority on the court.

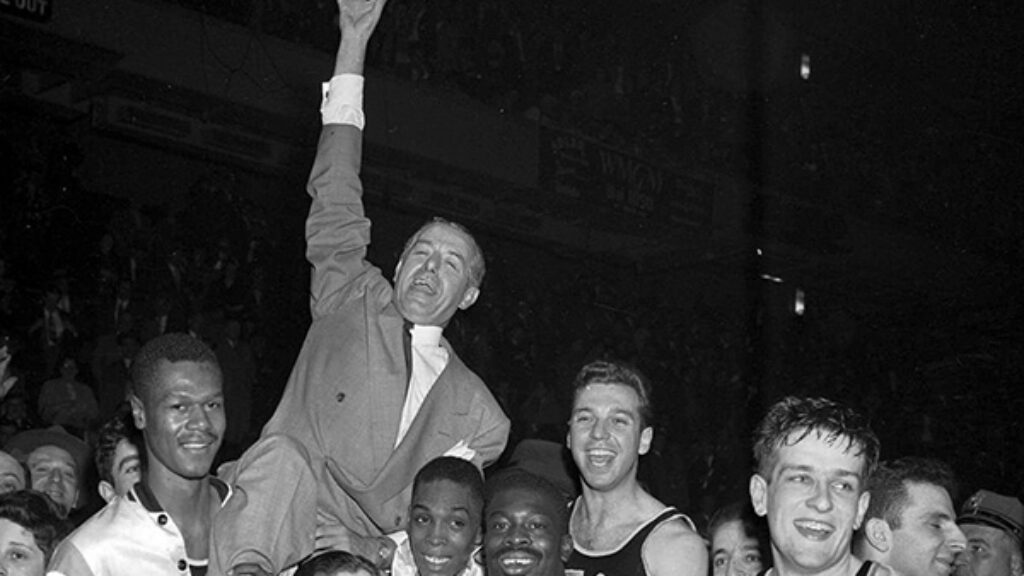

The Fix Was In

The 1951 basketball game that pitted CCNY, which fielded blacks and Jews, against the all-white University of Kentucky seemed less a meeting of schools than a clash of civilizations: old versus new, South versus North, prejudice versus tolerance.

The World is Round

The heckler’s guide to beating an antisemite.

Overturned Tables

Despite his incontestable Jewishness, Jesus never participated in a Seder as the Mishnah describes it any more than he intended for Judeans to abandon biblical law for the worship of God’s only begotten son.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In