Members of the Tribe

“You should be ashamed of yourself!” That’s what several unnamed callers from around the United States shouted over the phone at Michael Oren after the Forward carried a story about his behavior at a 2012 Christmas party at the home of legendary Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee and his wife, journalist and author Sally Quinn. The Forward’s reporter, Nathan Guttman, claimed that Oren had been seen “reaching for” the Christmas ham. But Guttman’s source, Mark Leibovich’s gossipy best-seller about the Washington elite, This Town, had only said that Oren had “hovered dangerously over the buffet table, eyeing” the ham.

(Courtesy of the author and Random House.)

If an Israeli ambassador to the United States can’t consume ham in public, he may still have to engage in something like pork-barrel politics. Oren tells us how he once had to field a call from Donald Manzullo, a Republican congressman from Illinois, who was outraged that 400,000 pounds of frozen carp from his district were not being unloaded in Israel. The U.S.-Israel free-trade agreement afforded Galilee carp farmers this protection, but Manzullo pushed hard, complaining not only to Oren but to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton:

“You think finding Middle East peace is hard,” Hillary blithely told reporters. “I’m dealing with carp!” Netanyahu called to question me, “What’s all this carp stuff?” I urged him to focus on Israel’s critical issues and leave the fish to me.

After the crisis was resolved through a one-time exception, Oren reports, “[a] now-composed Congressman Manzullo called to thank me and to ask, ‘Why do you Israelis need so much carp?’” Oren told the congressman that Passover was coming and carp is the main ingredient in gefilte fish.

Despite its serious subject, Michael Oren’s Ally includes a great haul of anecdotes. But this is not why the book received so much attention. What made its publication an event was what Oren said about the too-often misguided aims and detrimental impact of the Obama administration’s Middle East policy, especially its naïve and counterproductive manner of coping with the Iranian nuclear threat. Oren himself may or may not have been deeply involved behind the scenes in the development of Israel’s response to this policy, but even if, as Martin Indyk has claimed, he “was not really a witness to this particular chapter of history” but just someone “peeping through the keyhole,” this didn’t prevent his words from reverberating widely.

Even before it was officially released on June 23, Oren’s account of the years he served in Washington generated a great deal of controversy. On June 16, he published an op-ed on the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal entitled “How Obama Abandoned Israel.” The United States, he complained, as he had in his book, had repeatedly deviated over the past six years from its long-standing policy of close coordination with Israel. Worst of all, it had engaged in secret negotiations with Iran, Israel’s “deadliest enemy,” behind Israel’s back. The very next day, America’s ambassador to Israel, Dan Shapiro, derided Oren as “a politician and an author who wants to sell books” and whose account of recent events was utterly “imaginary.” Ambassador Shapiro couldn’t get Prime Minister Netanyahu to denounce Oren, but he did persuade Moshe Kahlon, the head of the party Oren now represents in the Knesset, to declare Ally a “personal memoir” that expressed neither his own viewpoint nor that of Kulanu.

After being interviewed about Ally by David Horovitz in The Times of Israel on June 18, Oren regretted (as he was running off to a meeting in the Knesset) that the discussion around his book had been too limited:

[W]e didn’t talk about Jews at all. There’s also a long section in the book about relations with the press. I really wrote so much of the book for the American Jewish community, to get in that discussion about us. (Sighs). Everything’s Obama and Bibi.

Oren wasn’t just complaining about the Horovitz interview, but about the overall response to his book. This is a complaint that has to be taken with a grain of salt, given Oren’s almost simultaneous admission that he rushed his book into print in order to solidify opposition within the United States to a bad deal with Iran.

What effect Ally and the innumerable reviews of the book by prominent pundits and veteran policy analysts (and even reviews of all the reviews) had on the summer’s debate over the Iran agreement is hard to measure. It does seem clear, however, that Oren’s critical observations about American Jews produced nothing more than temporary bursts of indignation. In a way, this aspect of the book and its reception is just another footnote to David Ben-Gurion’s run-in with American-Jewish Committee President Jacob Blaustein back in the early fifties. The prime minister urged the young Jews of America to make aliyah and Blaustein responded in high, almost biblical dudgeon that “[t]he future of American Jewry, of our children and of our children’s children, is entirely linked with the future of America.” But Oren’s Zionism, while fervent, does not turn on Ben-Gurion’s brand of “negation of the diaspora,” and it is worth thinking about its distinctive, and even distinctively American, features.

In one of the later chapters of Ally, after complaining about American-Jewish journalists and their frequently censorious coverage of Israel, Oren tells us that he

could not help questioning whether American Jews really felt as secure as they claimed. Perhaps persistent fears of anti-Semitism impelled them to distance themselves from Israel and its often controversial policies. Maybe that was why so many of them supported Obama, with his preference for soft power, his universalist White House seders, and aversion to tribes.

While this clearly echoes a long tradition of Zionist criticism of exilic Jewish spinelessness, it can be best understood, I think, as the kind of criticism that would inevitably cross the minds of Jews who came to Zionism by a very particular route. For Michael Oren belongs to a fairly small, unusual, but surprisingly influential group of American-Jewish baby boomers, one composed of individuals for whom Israel has been at the vortex of their existence for most of their lives. While some of them, like Oren, have made aliyah and become Israelis, most have remained in the United States, or at least gravitated back to it. And these people, too, vary in the degree of their attachment to Israel. For some, Israel is a component of their broader sense of Jewish identity, and remains a country to which they are strongly tied but which does not preoccupy them, except at times of emergency. For others, it is a place with which they became disenchanted, either through headlines or experiences, but from which they cannot even begin to sever themselves. For yet others, it remains the home where they for one reason or another did not succeed in making themselves at home.

In an interview in May with The Atlantic writer Jeffrey Goldberg, who figures prominently in Ally and definitely belongs to this group, President Obama almost seemed to cast himself as a member, too. The president reminisced about how he came to know Israel on the basis of images of the “kibbutzim, and Moshe Dayan, and Golda Meir” and how they inspired him to feel “that not only are we creating a safe Jewish homeland, but also we are remaking the world. We’re repairing it.” Obama does hold a Seder at the White House, and Goldberg has publicly labeled him the first Jewish president, but still the use of the first-person plural was astonishing, if for no other reason than that no one ever saw Moshe Dayan as a symbol of tikkun olam. What Obama failed to recognize, and certainly would not identify with if he did, is the way in which swashbuckling Israeli war heroes like Dayan used to mesmerize many American Jews, including Goldberg, who once jokingly described his younger self as “the Moshe Dayan of the Howard T. Herber Middle School” in Malverne, Long Island.

Other individuals who figure importantly in Ally, including, above all, Michael Oren himself, could also have described themselves as schoolboy Moshe Dayans. The New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman wrote in his first book, From Beirut to Jerusalem, that “high school for me,” in Minneapolis, between 1968 and 1971, “I am now embarrassed to say, was one big celebration of Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War.” Jonathan Pollard, the intelligence analyst who has spent three decades in prison for spying for Israel (and, as I write, is scheduled to be released on parole this November), was in high school in South Bend, Indiana in 1967. Years later he reported how astounded and emotionally intoxicated he had been by “the sight of Jewish tanks encamped on the banks of the Suez Canal and our paratroopers praying at the newly liberated Western Wall in Jerusalem.” The Six-Day War overwhelmed Michael Oren, too. A mere 12 years old at the time, he remembers his parents in West Orange, New Jersey murmuring about the danger of a second Holocaust, but above all how such worries were dispelled by “the miracle”—paratroopers dancing before the Western Wall in Jerusalem, “our paratroopers.”

Exhilaration at the outcome of the Six-Day War was, of course, widespread enough among American Jews, but their previous childhood experiences made it especially intense for Goldberg, Pollard, Oren, and other members of their particular sub-tribe, for they had each been victims of juvenile anti-Semites. When he was 11, Goldberg was frequently beaten up by “representatives of the more physical races: red-faced Irish kids, a cackling bucktoothed German boy, and the occasional Italian, the sort who took up smoking even before they grew underarm hair, and who blew up cats with M-80s.” Jonathan Pollard attended schools in which there were very few other Jews and, according to the report of Wolf Blitzer in his Territory of Lies, anti-Semitic bullies constantly beat him up, from elementary school through high school. Michael Oren grew up in a working-class neighborhood in West Orange, New Jersey, where he was the only Jewish kid on his block, and “rarely made it off the school bus without being ambushed by Jew-baiting bullies.” When he was in high school, his synagogue was bombed. The remedy for such anti-Semitism was what Goldberg was elated to see on his bar mitzvah trip to Israel: “Jews with guns, and not just .22s, but Uzis and M-16s and bigger guns than these . . . A Jewish tank!”

In high school and afterwards, Goldberg immersed himself in Zionist literature and dreamed of becoming an Israeli soldier, but it was only after a couple of years that he “dropped out of Penn and bought a one-way ticket to the Promised Land.” Following a stint on a kibbutz, he enlisted, went through basic training, and eventually became a military policeman at a prison full of Palestinians, as he recounted in his 2006 book, Prisoners.

Pollard too read voraciously about the Holocaust and Israel and made it to Israel to attend a summer science camp for gifted students at the Weizmann Institute, where he seems to have had a bad experience. He subsequently moved on to Stanford, where he convinced some of his amazingly gullible fellow students that he was a colonel in the Israeli Army and on the Mossad payroll, a fantasy which would have serious consequences for the American-Israeli alliance.

After a trip to Israel as a 15-year-old, Thomas Friedman read everything he could get his hands on about the country and befriended a Jewish Agency shaliach, “a sort of roving ambassador and recruiter,” who arranged for him to spend all three of his high school summers on a kibbutz. But he never seems to have contemplated aliyah. “I liked the way Israel made me feel,” he wrote, “as an American Jew—the pride it instilled in me and the way it stiffened my spine—but I was never convinced that having an Israeli identity could be an end in itself for me.” Instead of moving to Israel after high school Friedman went to Brandeis, stayed there until he graduated, and then obtained an M.A. in Middle Eastern studies at Oxford before making his way, famously, into journalism in Lebanon.

Friedman didn’t return to Israel again until 1984, when he became the Times’ correspondent in Jerusalem. He described the book that grew out of that posting, From Beirut to Jerusalem, as one about a

Jew who was raised on all the stories, all the folk songs, and all the myths about Israel, who goes to Jerusalem in the 1980s and discovers that it isn’t the Jewish summer camp of his youth but, rather, an audacious and still unresolved experiment to get Jews to live together in one country in the midst of the Arab world.

Michael Oren’s resemblance to Goldberg, Pollard, and Friedman goes beyond the early traumas and daydreams that they had in common. Like Friedman, Oren utilized his ties with Israeli emissaries in the United States to make his way onto a kibbutz after his first year in high school, and he repeated the performance in ensuing summers, marking the first steps in Michael Bornstein’s transformation into Michael Oren:

At eighteen I was on horseback rounding up cattle on the Golan Heights . . . Once wan and tender-looking, I became leathery and fit. No longer a stranger in my own land, I blended with my ancestors’ topography and conversed in their language.

Oren longed to become an Israeli—but not right away. Like Goldberg, Friedman, and Pollard, he attended an elite American university. He didn’t drop out of Columbia in the way Goldberg left Penn, since he felt that it would be best to finish his studies before joining the Israeli Army. When he eventually did so, he was determined to be a paratrooper, like the ones who had danced at the Wall in 1967, and he succeeded in becoming one. He fought in Operation Peace for the Galilee in 1982, but in September of that year he “left the hell of Lebanon” to continue to pursue Middle Eastern studies at the doctoral level in “idyllic Princeton.” After his PhD, Oren returned to Israel and led, most of the time, the precarious existence of a semi-employed academic until he published his history of the Six-Day War in 2002. Six Days of War, which was a best-seller in both America and Israel, changed his life:

For the first time, [my wife] Sally and I were able to buy a car that was not thirdhand and to give our three children rooms of their own. Overnight, I became a commentator on news programs, a frequent op-ed contributor, and a guest on The Daily Show and Charlie Rose. The lecturer once snubbed by academia was now a visiting professor at Yale and Harvard. And the editors who once rejected me with form letters now published two of my novels . . .

All of which set the stage for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s surprise selection of Oren, a man with no previous diplomatic experience whom he barely knew and who did not even belong to his party, as Israel’s ambassador to the United States in 2009. It was a job he had dreamed of since meeting as a 15 year old with Yitzhak Rabin, the hero who held it at the time.

By the beginning of the 21st century, only one of our four public school Moshe Dayans lived in Israel. It was never Friedman’s intention to do so, and Pollard, of course, obtained Israeli citizenship only after he was incarcerated in the United States for espionage. Goldberg had made aliyah, but returned to the United States, partly because he had fallen in love with an American woman who didn’t want to live in Israel, and partly because of what he called “the coarseness of life in Intifada Israel.” But even as Goldberg ironically admitted that America had in the end become his “Promised Land,” he remained committed to the historical and political claims of Zionism and “susceptible to the demands of blood and tribe.”

Michael Oren has the good fortune to be married to an American-born woman, Sally Oren, a colorful figure in her own right—she spent her teenage years at the heart of the 1960s psychedelic rock movement in San Francisco hanging out with members of the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane (who even wrote two songs about her)—who is happy to live in Israel. He is well aware of the hardships of Israeli life and by no means blind to the country’s faults, but he seems never to have felt any inclination to return to the United States. The best explanation for this is, I think, that he really is an unshakable idealist. But he’s a forgiving one, too. Oren would no more chastise his good friend and, as he takes care to note, fellow IDF veteran Jeffrey Goldberg for leaving Israel than he would anyone else. “I was,” Oren tells us,

the first Israeli ambassador to greet gatherings of Israeli immigrants to the United States. As one who had given up his U.S. citizenship to pursue an Israeli dream, it was strange to address those who, for financial or family reasons, had forfeited that dream to become Americans. But they remained avidly committed to Israel, and Israel, I believed, should embrace them.

Goldberg clearly passed Oren’s avidity test—he is the journalist quoted most frequently and most approvingly in Ally (and whose particular judgments Oren had ample grounds for calling into question, had he been so inclined). But so did Jonathan Pollard, the only person in his book whom Oren describes as having had a background similar to his own. “Pollard,” he writes, “roughly my age, was disconcertingly familiar. Like me, he suffered anti-Semitism as a youth, bore the burden of the Holocaust, and exulted in Israel’s rebirth.” And Pollard, like Oren, believed that “‘[t]here was no difference between being a good American and a good Zionist’” and that “‘American Jews should hold themselves personally accountable for Israel’s security.’”

Pollard, however, had made the unjustifiable decision to break the law, and consequently, instead of becoming “a free man in the Land of Zion,” became “federal inmate number 09185-016.” But if Pollard’s deeds were wrong, they did not place him beyond the pale, and Oren willingly performed his duty, as the Israeli ambassador, to seek the release from prison of “an Israeli citizen for whom the State took responsibility.” For a year, in fact, he tried unsuccessfully to meet with him in prison, but Pollard wasn’t interested. It is perhaps ironic that Pollard forfeited the opportunity to get together with the man who more than any of his American-born contemporaries had actually lived out his own youthful fantasies.

After Jeffrey Goldberg, Thomas Friedman is the journalist Oren quotes most frequently—and almost always disapprovingly. The ninth and last time he mentions Friedman he describes him as “so rarely right on Middle Eastern issues.” I don’t think it is just his misjudgments or his naїveté that irk Oren (he mentions his more or less like-minded fellow Times man Roger Cohen only once, after all) as much as Friedman’s lack of avid commitment to Israel, the kind of tribal solidarity one ought to expect from someone with his background. Of all of Oren’s references to Friedman the one that I think does the most to explain his antipathy is his account of a conversation after Friedman published a column in which he described the standing ovation Netanyahu received from Congress as “‘bought and paid for by the Israel lobby.’”

I called Tom the moment the article came online and urged him to retract it. “You’ve confirmed the worst anti-Semitic stereotype, that Jews purchase seats in Congress.” But Tom remained impenitent. “For every call I’ve received protesting, I’ve gotten ten congratulating me for finally telling the truth,” he said. “Many of those calls were from senior administration officials.”

Oren diplomatically refrains here from spelling out what he thinks Friedman had unwittingly revealed about himself in this conversation.

Oren is reported to have said that the non-Orthodox and intermarried Jews in the Obama administration “have a hard time understanding the Israeli character.” But one can’t help wondering whether Oren is capable of seeing the world through the eyes of a typical American Jew. He is, to be sure, well aware of the facts. He takes note, for instance, of the soaring intermarriage rates and the fact that fewer than a third of American Jews have ever visited Israel, but he seems to be constitutionally unable to grasp just how distant large sectors of the community now feel from Israel and just how fully they feel at home in the United States.

It’s not, of course, that he wants American Jews to feel anything other than at home here. Unlike many other Zionists, who have coupled analyses of diaspora Jews’ fears and behavior similar to his own with calls to recognize that the Gentiles will never accept them, Oren tells them that they can have their cake and eat it too. They can, precisely by being good Zionists, be better, more engaged citizens of the United States. As Oren learned in his adolescence, this is an argument that goes all the way back to Louis Brandeis. From the start, Oren’s own Zionism, like Brandeis’s, was tied up with American patriotism, because Israel and America both stood for freedom and democracy. Jeffrey Goldberg, in Prisoners, admits that his “Americanness is unconquerable,” and Oren could no doubt say the same of himself. He would never have dreamed of relinquishing his U.S. citizenship had this not been a requirement for the job he held in Washington, and it was by no means an easy thing for him to do. When he recounts, at the beginning of Ally, how he had to acknowledge officially that he would henceforth “become an alien with respect to the United States,” it is evident how bereft he felt.

Oren’s book has drawn a lot of attention for its portrayal of an Israeli-American relationship gone awry. But one should not overlook its remarkable conclusion. In one of the book’s few literary flourishes, Oren relates how on July 7, 2014, nine months after he had moved back to Israel and just before Israel’s 50-day war with Hamas, he and his wife attended a bar mitzvah party at a kibbutz in central Israel. In the midst of the celebration, they heard an air raid siren and ran for cover “under [a] corrugated awning,” waiting to see where the rockets would land:

I held Sally’s hand and glanced over my shoulder just as two Hamas rockets roared in. Then, with twin booms that rattled the tin overhang and shook the ground below, the missiles exploded. Iron Dome interceptors, developed by Israel and funded by the United States, scored perfect hits. For moments afterward, as we emerged into that uncertain night, the glow of those bursts hovered over us, beaming like kindred stars.

This star-spangled finale reflects both gratitude for what the Israeli-American relationship has been in the past and hope for what it can yet mean in the future. But it is also something of a cliffhanger. What will become of the relationship? Will it recover from the Obama-Netanyahu imbroglio? And what role will Michael Oren play in determining its fate? He’s only a Knesset member now, but there are people who envision a greater role for him. Shortly after the Israeli elections, his friend Jeffrey Goldberg mused online:

If Israel’s government were organized in a semi-sane way, then Oren would obviously be the country’s next foreign minister, or at least deputy foreign minister—or, at the very least, Adviser to the Prime Minister on Managing Relations With Other People.

Needless to say, that hasn’t occurred. But who knows? What Oren says of Jeffrey Goldberg’s life—after Fidel Castro telephoned him for an interview—is equally true of his own: It reads “like an excerpt from Ripley’s Believe It or Not,” or at least the fantasy of a certain kind of idealistic young Zionist who came of age a generation ago.

Suggested Reading

Revealer Revealed

Earlier this year, an email announcement of a publication made its rounds among scholars of Jewish studies. Written in the flowery Hebrew of the Eastern European Jewish Enlightenment, the advertisement proclaimed that the work would “reveal all secrets.”

A Cipher and His Songs

Avraham Halfi faced outward, a gifted comic performer, and inward, a lyric poet of resonant privacy.

Power and the Voice of Conscience: A Lost Radio Talk

On January 19, 1947 a young rabbi named Emil Fackenheim got behind a microphone to give a searing radio address about the Jewish refugees from Europe. He himself had been one only four years earlier.

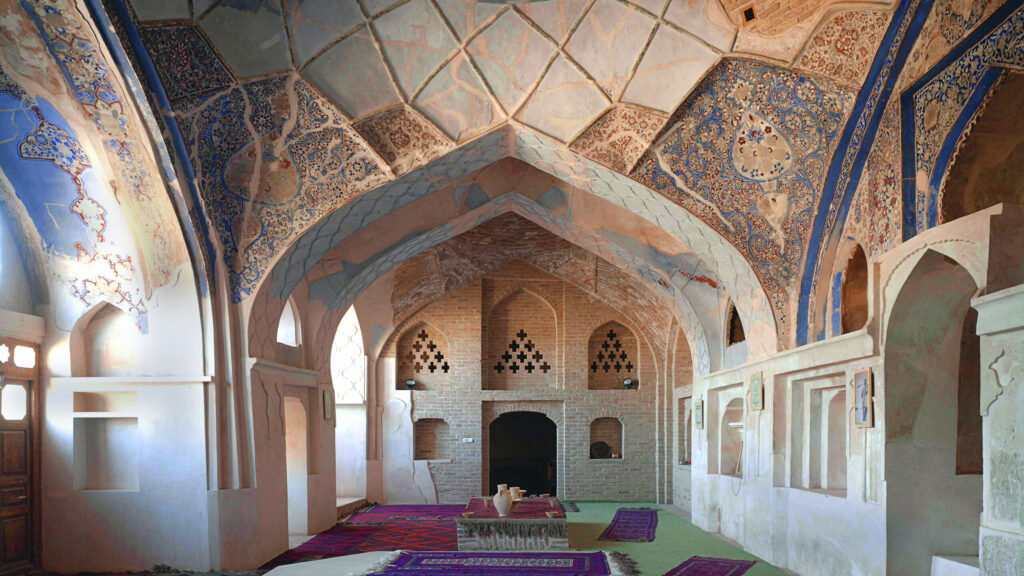

Now a Museum, the Synagogue was Meticulously Restored . . .

The synagogue is a mikdash me’at, a little sanctuary or temple. But what really makes a shul holy and how should they be remembered?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In