Yosl Bergner’s Jewish-Israeli Genius

I have known the painter Yosl Bergner for something like 65 years, since he and his new bride Audrey visited my family in Montreal when I was just emerging from childhood. For the last three decades, my husband Len and I have visited the Bergners in their now-famous home and studio in Tel Aviv almost every year. So it was with a sense of real personal joy that I participated in the public festivities around Yosl’s 95th birthday last spring, an age he will reach in October. Long an icon of the Israeli art scene, Yosl reports that he is no longer considered contemporary—pronouncing the word “achshavi” with the merriment of one who knows the difference between trendiness and talent. This was all the more reason to celebrate his genius, though our private conversation often turns to family ruminations more readily than to our common interests in literature and art.

When we visited him in 2000, shortly after my mother died, I braced myself and asked Yosl, “Do you think your father and my mother were having an affair?” Yosl answered, “Halevai!” If only! This was vintage Yosl: exploding the anxiety of my question with laughter by implying that any such consummated liaison could only have benefited both parties. It also described Yosl’s relation to his father, which was what psychologists call “parentification,” in which the child takes on the role of the parent. Yosl’s father, Melekh Ravitch, was reputed to be a great womanizer, but Yosl had figured out that the problem lay in the other direction. His father was too uncomfortably repressed and had never found his natural place in the world. Though my subject here is the child, not the parent, I came to know Yosl by trying to understand relations between him and his father, which included relations between his family and mine.

Melekh Ravitch, pen name of Zekharye-Khone Bergner (1893–1976), was one of the most prolific Yiddish poets and essayists of his generation. Before the First World War the writer Yitzhok Leybush Peretz (I.L. Peretz) in Warsaw was the acknowledged central figure in the constellation of Yiddish literature, but when Peretz died in 1915 the position was unclaimed until Ravitch moved from Vienna to Warsaw in 1921 and took up the administrative aspects of that role. He compensated for his reduced literary stature—no one again ever loomed as large as Peretz—by dedicated and methodical effort. Between 1924 and 1934 Ravitch served as executive secretary of the Association of Jewish Writers and Journalists (Fareyn fun Yidishe Literatn un Zhurnalistn in Varshe), where he organized, among many other initiatives, a speakers’ bureau that sent Yiddish poets and writers to Jewish communities in Polish towns.

In 1941, propelled by the Second World War, Ravitch landed in Montreal, Canada, where he assumed an analogous function in the local literary community. The Jewish Public Library, established in 1914, badly needed a new infusion of energy which Ravitch supplied, just as the institution supplied him with a center of operations and a helpmeet—its librarian, Rokhl Eisenberg—who eventually became his second wife. Among his other accomplishments, Ravitch organized lectures and programming for the Yiddish community that expanded with the arrival of refugees after the war. He also became one of the mainstays of the Yiddish daily newspaper Keneder Odler (Canadian Eagle) and turned the Yiddishe Folksbibliotek into what Yiddish calls an adres—a central meeting point for Yiddish culture.

This is the world in which I grew up. My mother, Masha Roskies (heroine of my brother David’s memoir Yiddishlands), had also hit the ground running when our refugee family landed in Montreal in October 1940. Although the rest of the extended Roskies family gravitated to the prestigious area of the city known as Westmount, Mother moved us closer to the immigrant and Yiddish-speaking Jews and institutions like the Jewish Public Library. As soon as Ravitch came on the scene, Mother threw her prodigious energies behind him and his projects, including raising money for the publication of his books. Mother did this through a system of prenumerantn, subscribers who bought advance copies of the book to subsidize its publication. Once the book appeared, she organized a literary evening in its honor. Although this did not solve the problems of wider distribution, it worked well for local poets and writers such as I.J.Segal, Ida Maze, and Mordecai Khosid. But Ravitch was preeminent and Mother felt especially responsible for him.

The friendship between Masha and Melekh resulted in my older brother Benjamin and, somewhat later, me being sent to him for private lessons in literature. I would hike to Ravitch’s rented room, where as a strict vegetarian he kept some fruit and vegetables on the windowsill and lived what seemed a monastic existence. This impression of asceticism was reinforced by the fact that he drank no alcohol, not even wine on Pesach. It was further supported by the personality of Rokhl, an ideological communist who was both a superb librarian and one of the most rigid persons I had ever met. Ravitch seemed to me a self-disciplinarian who could have used an indulgent and fun-loving helpmeet rather than the starchy woman he had chosen. Yosl, however, thought her lovely when he met her and she became his stepmother, and it is possible that my impression of Rokhl was influenced by Mother’s competitive dislike.

We were honored to have Ravitch and Rokhl join us annually for Passover Seder, and my own family still sings “Ki lo noeh” (For to Him Praise Is Proper) to the melody that Ravitch introduced at my parents’ table some 70 years ago. But what I recall most vividly was the explanation he gave one year for the concluding song “Chad gadyo” (The One Kid). He said that if you looked at the sequence of crime and punishment as it is arranged in the layered stanzas of the song, the cat was guilty for eating the kid but the dog then justified in biting the cat; the stick was guilty and the fire innocent. Continue the scheme of guilty and innocent in the ascending order through water, ox, butcher, and Angel of Death and—here was the crux of the matter!—the Holy One was guilty for killing the Angel of Death.

Ours was a dinner table of open discussion, and argument was encouraged. But this idea of evil at the top of the pyramid was one of the most perverse things I had ever heard from an adult, and I felt sorry that Ravitch felt impelled to pit himself so unequally against God. If our guest wanted to spare animals by not eating their flesh, why not show some respect for God who, according to the haggadah, had Himself alone led us out of Egypt? Being something of a skeptic myself, I also wondered whether Ravitch knew how much extra anxiety it cost my mother to prepare his special Passover vegetarian meals.

The complicated feelings I harbored for Melekh Ravitch made it that much more delightfully exciting to meet his son and new daughter-in-law during their stay in Montreal in 1949–1950. Yosl and Audrey brought brightness and joy into our Yiddish world. I emphasize the “Yiddish” because Audrey, who was Australian and not Jewish, immediately began studying Yiddish with her father-in-law, and this is the language we mostly spoke when we were all together. Yiddish, the repository of our Jewishness, was in those days burdened with grief. Every refugee-survivor who visited our home in the immediate post-war years brought fresh details of murdered family members, friends, and former neighbors. What a contrast between them and this vivid and beautiful young couple—Yosl and Audrey, both artists—who existed wholly in the realized present. They seemed untouched by misery and content to be.

Were they frustrated by lack of proper working conditions? Probably. Were they concerned about the future and less serene than they appeared? Undoubtedly. But their presence confirmed for us the value of our Jewish inheritance in a way that our parents had not been able to do. It was one thing for Melekh Ravitch to tout the greatness of I.L. Peretz and to take pride that Peretz had once praised his writing. But it was Yosl’s illustrations of the Peretz stories that proved how important—how fascinating—Peretz really was.

Illustrations to All the Folk Tales of Itzchok Leibush Peretz, published by Hertz and Edelstein, Montreal. Courtesy of

the artist.)

Yosl’s illustrations of Peretz’s Folkstimlekhe geshikhtn (Tales in the Folk Manner) were displayed at the Workmen’s Circle building in Montreal and published with introductions in Yiddish and English. In the exhibition catalogue Yosl provided the captions for the paintings and drawings, as he later did for his Kafka series, so that we know the specific moments in each story that the work is bringing to life. His favorite subject seems to have been Peretz’s well-known figure, Bontshe Shvayg, or, Bontshe the Silent—the porter toting back-breaking loads through streets crowded with people who never hear “how his spine cracks under the weight of his burden.”

But at least one of Yosl’s paintings of the Bontshe story goes against Peretz’s obvious intention. You may recall that although no one in the story heeds Bontshe’s agony on earth, his death is greeted in heaven by cascades of appreciation for his saintliness and forbearance. At the end of his perfunctory heavenly “trial,” where the prosecutor says that it is now his turn to remain silent, Bontshe is told that in recompense for his earthly travails he may ask for anything—anything at all. Bontshe replies with a smile: “Nu, oyb azoy vil ikh take ale tog in der fri a heyse bulke mit frishe puter.” “Well, if so, every morning I want a hot roll with fresh butter.” Thus does Peretz expose a heavenly scheme that cannot compensate the sufferer who has never learned to demand his due. The prosecutor’s bitter laughter indicts the culture that created such passivity, and the heavenly court hangs its head in shame.

Peretz had written the Bontshe story in 1894, during the formative years of the Jewish labor movement. Interpreting it more than half a century later, Yosl shows the scrawny hero behind a white festive table that holds candlesticks, kiddush cup and pitcher, an open manuscript, and a single roll. Some details in the painting suggest the celestial setting, but bearded Jews have replaced the angels (though one of them has the suggestion of wings). In visual parody of the Last Supper, they surround a Jesus-like Bontshe who is elevated above them. The eyes of the men are closed or hooded, as though they were concentrated inward in contemplation. They are together yet each is alone. Two of the Jews are in prayer shawls, and one in the background has just lit two Sabbath-cum-memorial candles that are the only glowing items in the picture. The Polish Jews who once stood accused of ignoring Bontshe had themselves been consigned to their unmarked graves. It was time for the Jewish artist to take back their last supper from Christian art. Whereas Peretz highlights the unmet expectations of divine justice, Yosl offers the ending Peretz might have offered the Jews of Europe had he updated the story in 1950.

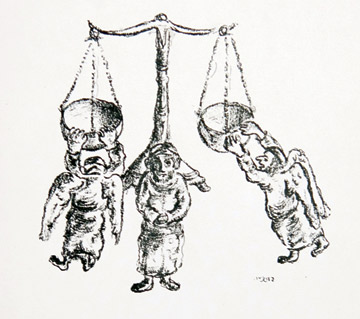

Yosl’s Peretz exhibition, which apparently sold pretty well, persuaded his father that he was a real, working artist. The Montreal poet I.J. Segal said, “Bergner naturalized that which Peretz had idealized,” but there were also works in which Yosl rendered in a comic vein that which Peretz had issued as protest. Peretz’s “Di dray matones” (The Three Gifts) is a parable about Judaism’s most sacred values. The three Jews in the story are brutally murdered and die as martyrs for nation, morality, and faith. When I studied this story in Jewish day school, it left indelible images in my mind of thieves thrusting the knife into the Jew who would not give up his sack of earth from Eretz Yisroel, the girl dragged by horses through the streets with her skirt pinned into her flesh to protect her modesty, and the Jew running the gauntlet twice to retrieve his fallen yarmulke. Yosl, however, chose to illustrate the sentence, “The good and evil deeds of the soul balanced each other exactly,” through a swinging scale with three delightful angels, two of them hanging on for dear life to their afterlife. Let me always remember the story that way! All of which is to say that when Yosl took over I.L. Peretz from his father, he claimed full ownership of the material, as a master rather than apprentice.

Years later, Yosl did the same with Kafka, whom Ravitch began translating into Yiddish in 1924. Yosl was proud that his father had been the first Yiddish writer to recognize Kafka’s genius, and the illustrations he did for Ravitch’s book were part of the Kafka series that cemented his international reputation. Yosl himself felt a powerful artistic affinity with Kafka, and he adapted the style of Kafka’s marginal line drawings for his Kafka works. Nonetheless, I don’t feel in Yosl the angst that Kafka conveys, and—at least for me—this is much to Bergner’s advantage. Kafka did not feel at home in his German language, did not feel at ease in his bourgeois home, did not love and honor his insensitive father, did not feel comfortable in his own skin. In a widely quoted image from a letter to his friend Max Brod, Kafka describes Jews “with their hind legs fastened to the Jewish traditions of their fathers and with their forelegs getting no ground under their feet. The despair thus ensuing translates into inspiration.” Yosl understood such anxiety, but he had already found his footing and was moving forward. Part of this was thanks to Ravitch, who was content to have his son become an artist—as long as he did not give him too much competition—and Yosl, who is a terrific storyteller, obliged his father by choosing another medium for his art. (Happily, his friend Ruth Bondy transcribed some of Yosl’s stories in a collection that was published in the 1990s in both Hebrew and English.).

Whereas Kafka’s father had transitioned from Yiddish to German and downplayed his Jewishness in becoming a respectable Czech burgher, Ravitch after the First World War moved culturally in the opposite direction. He left his native German and Polish languages to speak Yiddish and moved from Vienna into the heart of Jewish Warsaw. As the son of such a father—one who rebelled against the bourgeois ideal by becoming a Yiddish writer—Yosl could legitimately take up a career of art. Yosl was born into the kind of creative and cultural security that Kafka craved and raised in a household so unorthodox that he was ready for a stable marriage and a routine of hard work. When Yosl and Audrey later settled in their cozy neighborhood of Tel Aviv, they were the ones to thwart developers because they wanted to preserve things just as they are.

We are accustomed to rebellions of sons against fathers, but Yosl came at modernism from the other side: Ravitch the modernist may have dulled for his son some of the novelty of novelty. Unlike earlier Yiddish writers like Mendele Mokher Seforim and Sholem Aleichem who adopted homey pen names for their informal storytelling style, Ravitch chose for himself the pen name Monarch—King—Melekh. He appears to have done this without an iota of irony. One can well understand the aesthetic impulse for such a move. Yiddish was the lingua franca of the Jewish masses, but the modern writer intended to liberate the language and its speakers from their mundane associations. Why not a royal Yiddish? Why not a majestic Jewry and an author who believed in his elevated mission? Moreover, Ravitch demonstratively declared himself a follower of Spinoza rather than the rabbis. With Uri Zvi Greenberg, Peretz Markish, and I.J. Singer he formed the literary gang Khaliastre (Gang) and violated as many conventions as expressionism allowed. In defiance of the Jewish ideal of modesty, Ravitch wrote Nakete Lider, Naked Poems, which Yiddish scholar Avrom Novershtern calls “one of the most representative achievements of the modernist revolution in East European Yiddish poetry.”

For his part, Yosl seems never to have been tempted to work on a heroic scale. His good-natured eroticism he ascribes to having beheld in childhood the buttocks of their Polish maid. It finds expression in the ripe bisected apples that he has been painting much of his career. Yosl loved the homey realities that Ravitch was trying to transcend, and he domesticated what Ravitch tried to make exotic. His work was accessible to the Jewish street, to the uncultivated eye. The subtle thinking, parody, symbolism, and iconography in his paintings are conveyed in a manner that is welcoming rather than alienating.

Yosl holds nothing back in his art or himself. He is known to oblige café owners, art dealers, friends, and practically anyone who appeals to him with drawings, illustrations, and autographed souvenirs. When it came to choosing a signature for his work, Yosl tried out several, but like his close friend, the late Yiddish writer Yosl Birshteyn, he became known by the diminutive Yosl, which he sometimes signs in Yiddish.

Father and son likewise differed in their concepts of home. World travel was one of the great dreams of Ravitch’s generation of Yiddish writers, just as it is for Israelis today and for similar reasons: Worried about their potential parochialism and belittled for their civilizing virtues, they needed to seek out presumably broadening culture abroad. Ravitch traveled the world. In 1937 he published Kontinentn un okeanen (Continents and Oceans), a book of lyrics, poems, and ballads described as “Asiatic, African, European, Australian, Oceanic, Pacifist, and Ideational (patsifistishe un ideishe), Vegetarian, Jewish and Enclosed in Four Walls (Yidishe un in-fir-ventishe).” The best-known of these poems, “Tropical Nightmare in Singapore,” confesses that in all the seven worlds and on all the seven seas, “The singer, the king, is always alone.”

Vayl af ale zibn veltn

Un af ale yamen zibn

Iz der zinger, der meylekh

Aleyn af der velt geblibn.

Yet he continues to try to escape this solitude in ways that have failed him before.

Thankfully, Ravitch also realized there was something practical at stake in leaving Poland in the 1930s. He was able to bring his family to Australia so that they were spared the fate of those who remained under Stalin and Hitler. Yosl, his sister Ruth, and their mother, as well as Melekh’s brother Hertz Bergner, took refuge in Australia before the war. Yosl studied painting at the National Gallery School in Melbourne, joined the Australian Army at the outbreak of World War II, and served for its duration before returning to Australia to establish himself as a painter. He and Audrey could have settled in Australia or Canada or perhaps in the United States, but after that year in Montreal they moved to Israel, first to the artists’ colony in Safed and then to Bilu Street, named for the pioneers who left Russia for Palestine in the early 1880s.

Ravitch and Rokhl tried joining them in Israel but they soon returned to Montreal. Yosl and Audrey stayed: impossible to visit with them without realizing how embedded they are in their neighborhood of Tel Aviv and their community of writers and artists, as though theirs was the cultural hub that Ravitch had dreamed of creating. Though for a couple of decades, with his friend the writer and playwright Nissim Aloni, Yosl cultivated an image of bohemian inebriation, he was always more the loyal friend, responsible husband and father, loving son, and citizen. In 1978, Yosl and his friend the neighborhood barber won the lottery jackpot, so that he was able to buy the small building adjoining his home to use as a studio. There people still drop by to discuss their marital problems, artistic disputes, and bureaucratic snafus.

I lost touch with Yosl and Audrey for several years after they left Montreal, but in 1957 my husband Len and I spent the summer in Israel as newlyweds and visited them at the urging of Melekh Ravitch. They had just made the move from Safed to Tel Aviv and told us that Ravitch had “given” us two paintings of theirs as a wedding gift. We were to choose one of Yosl’s and one of Audrey’s and take them back with us to Montreal. It felt like robbery, but they insisted on carrying out Ravitch’s wish (parentification again).

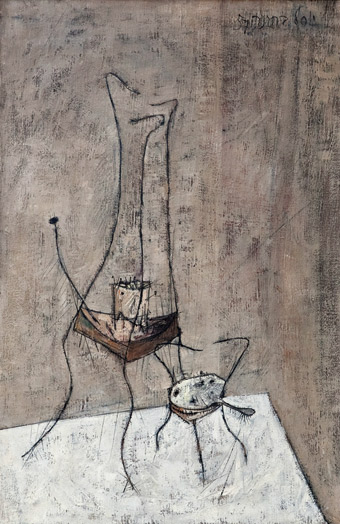

Audrey gave us a wonderful landscape of Safed. Yosl brought out several canvasses and asked us to choose from among them. He was then painting what I called his “refugees,” household objects—a lamp, a grater, dented cups and pitchers—objects that had been subjected to neglect or plunder, bearing unmistakable resemblance to the people with whom such domestic items were associated. The paintings reminded me of the friends of my parents we met that summer who were not olim, that is, immigrants who had ascended to the land of Israel, but rather pleytim, refugees who had come seeking shelter. Frightened that we might select something too valuable for him to part with, we finally chose a painting Yosl called Mother and Child. The two unfamiliar items in the painting—identified for us as primus camp stoves—were scrawnier versions of the anthropomorphic household items in the other works. When I said this was the one we wanted, Yosl said he was glad we had not gone for one of the brighter works.

It is hard to be a refugee. If I did not know this well enough from my own experience in childhood, I learned it from the people we met in Israel that summer. One family had lost all their wealth and standing. One couple had lost a son. A man had lost his wife and child; his only surviving image of them was the photograph that my mother had sent him from the album she had salvaged from Europe. In our travels we saw signs everywhere of building, blossoming, and reclamation, but Yosl’s paintings of neglected objects showed what was really going on among the new arrivals. He said, “Whatever colors I pour into the canvas, they come out gray,” which certainly wasn’t true of all his work.

Our Mother and Child is both topical and ageless. The stoves recall a precise phase in the history of the Yishuv of Palestine, reminders of deprivation that was practically over by the late 1950s. Yet animation of objects is a modern form of abstraction that expresses an essential humanity. The painting was humorous and at the same time deeply affecting. This was every mother who had rescued her child and hoped to keep holding its hand in the absence of a recognizable world. Mother and child is a familiar subject of Western art; here it is stripped to the basics, yet emotionally charged to the limit. Much of Yosl’s work is simultaneously plain and sublime, reduced and amplified, self-critical and self-confident.

Yosl loves to retrieve lost objects. I associate his work with words like reclamation, repossession, and if you allow me—Yosl might not, inflated terminology does not suit him—redemption. Yet we would be leaving something out if we did not recognize that he is a rescuer, a redeemer. His uncle Monia, a year older than his father, had run off to Palestine in 1910 to transform himself into the pioneering Moshe Harari. Moshe/Monia wanted to be an artist. Restless in Palestine, he returned to Vienna to study art but could not find a balance between competing needs and ambitions. He shot himself and died a half year after Yosl was born, which meant that the child could not be named for its uncle though this would almost certainly have been the case had he been born a half year later. Yosl keeps in his studio a large photograph of his uncle in the adopted Bedouin style of the earliest Jewish watchmen, but he loves pointing out the contradictions in his uncle’s adopted identity—the laced black shoes peeking out from under the abaya and an elegant walking stick Moshe had carved with his initials. He also keeps his uncle’s paintbox near at hand in his studio.

An article that appeared in 1998 entitled “Israeli Art On Its Way to Somewhere Else” includes Yosl’s work among the Israeli art that seeks to undermine the Zionist spirit. The article says that some of Yosl’s works portray the pioneers “as a rabble of false idealists who descended on the land only to corrupt it with their presence,” that they “strip the first Jewish settlers on the land of their heroism.” No one can deny that there is in Israeli culture this tendency to debunk Zionist aspirations and national achievements, but though Yosl’s work has been included in exhibitions of that sort, I see in his interpretation of the pioneers, the halutzim, a very different impulse to capture the difficult and sometimes—as in the case of his uncle—impossible attempt to reconcile the urban sophistication of Europe with the elemental struggle for survival that marked the early years of the Yishuv.

Among some my favorite of his paintings are those of pioneers rendered in exceptionally rich “Renaissance” colors to suggest their incongruous adaptation to allegedly primitive kibbutz life. The Orchardists, in this vein, shows a formally dressed couple and several other suited men with caps crowded around a table where a skeletal but predatory white bird has descended beside three oranges and a samovar. Thanks to that samovar and the formal attire, some people thought the painting was called Tea Drinkers, which would make them tea-drinking orchardists, cultivated pioneers.

The typical Bergner halutz, with eyes that might have belonged to Monia Bergner, carries the ripe harvest that he has sown and reaped. This odd Jew with a Polish cap on his head bears not merely plants or food, but bikkurim, offerings of the land. He displays what the soil of the Land of Israel yields when it is lovingly cultivated. Just as Yosl and Audrey, perhaps paradoxically, brought Jewishness home to us in Montreal when I was a child, so they refreshed Israel with their unfettered spirit. Half teasing, I call them my favorite Zionists. Without his Australian wife, I don’t know whether Yosl could have felt as much at home as a confirmed Jew in the Land of Israel, but then I don’t know anyone who makes Yiddish or Israel feel more attractive than Audrey, who often still longs for her native Australia. Jewish life has always been enriched with such paradoxes. Just as the Israelites brought the bones of Joseph to rest in the Land of Israel, Yosl brought the spirit of his father’s brother Monia/Moshe to rest where he had found no rest. His work brings the “golus,” the diaspora, home; the gray and the green are his blue and white.

Israel’s dynamism ensures that artists go in and out of fashion, and some Israelis want their art to “move on,” in one direction or another. Many Bergner canvases undoubtedly draw on the traditions of European art and evoke the culture of the Jews of Eastern Europe. His second retrospective exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum in 2000 opened with childhood drawings that were preserved by his father, and even his paintings of pioneering Israel convey the persistent weight of the European past. Yet Yosl always tweaks the traditions in which he works. It would be strange if this painter who brought such buoyancy into the Jewish world should come to be associated with the pastness of the past. Israeli art will surely be richer if it absorbs its own traditions.

When all is said and done, and despite fantasies of both generations, I believe that relations between Yosl’s father and my mother remained chaste. Their adventure, like Yosl Bergner’s (may he enjoy long years), was in the making and enjoyment of art.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Wisdom and Wars

If it were fiction, Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom would be the greatest English war novel.

I, Terrorist

Whither the great anti-American novel?

Trilling, Babel, and the Rabbis

Part of Trilling's mystique came from the way he seemed "to be a Jew and yet not Jewish."

Out of the Ghetto

Are they for the Jewish state or against? A new book from Israel distills recent scholarship on the haredim.

firebird1878

This is beautiful. How can we thank the world for Ruth Wisse?