Jews, Revolutionism, and Doublethink

In her memoir of Russian intellectual life under Stalin, Hope Against Hope, Nadezhda Mandelstam recalls that her husband Osip had “an occasional desire . . . to come to terms with reality and make excuses for it. . . . At such moments, he would say that . . . he feared the Revolution might pass him by if, in his short-sightedness, he failed to notice all the great things happening before our eyes.” She immediately explains that this mood can’t just reflect one person’s psychiatric stress since it was so widely shared. “It must be said that the same feeling was experienced by many of our contemporaries, including the most worthy of them, such as Pasternak.” Her most-quoted sentence follows:

My brother Evgeni Yakovlevich used to say that the decisive part in the subjugation of the intelligentsia was played not by terror and bribery (though, God knows, there was enough of both), but by the word “Revolution,” which none of them could bear to give up. It is a word to which whole nations have succumbed, and its force was such that one wonders why our rulers still needed prisons and capital punishment.

This phenomenon of “revolutionism,” a love and veneration for revolution not as a mere means but as an end in itself, had already been recognized in Mikhail Gershenzon’s famous 1909 anthology, Landmarks: A Collection of Articles on the Russian Intelligentsia. But, of course, Gershenzon and his contributors could not know how revolutionism would evolve during and after the revolution. For convenience, we can distinguish three kinds of revolutionism: the prerevolutionary embrace of terrorism and wholesale destruction, a second sort experienced during the Russian Revolution itself and its immediate aftermath, and a third predominating after the new regime was established.

Nadezhda Mandelstam was describing the third type of revolutionism, on which I intend to focus, but of course this phenomenon would not have been possible without the experience of the revolution itself. When the Bolsheviks overthrow the provisional government in November of 1917, Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago muses, “This unprecedented thing, this miracle of history, this revelation comes bang in the very thick of the ongoing everydayness . . . Only what is greatest can be so inappropriate and untimely” as revolution, he notes. But he soon recognizes that he has allowed words and abstractions to blind him, and he envisions the consequences: “Was it possible that he must pay for that rash enthusiasm all his life by never hearing, year after year, anything but these unchanging, shrill, crazy exclamations and demands, which became progressively more impractical, meaningless, and unfulfillable as time went by?”

What entranced Zhivago was an experience of time that anthropologist Victor Turner famously called liminality: a moment of transition when all definitions are in flux and everything seems possible. It is easy enough to see how revolution could seem like such a moment. To use Engels’s famous phrase, this was the leap from the kingdom of necessity to the kingdom of freedom—with freedom here meaning not the power of the individual to do what he likes but of the collective to reshape all life. As Trotsky argued, “Communist life will not be formed blindly, like coral islands, but will be built consciously . . . Life will cease to be elemental.”

Trotsky confidently predicted that all nature would be transformed, or as he put it, “nature [itself] will become ‘artificial.’ . . . In the end, he [man] will have rebuilt the earth, if not in his own image, at least according to his own taste. We have not the slightest fear that this taste will be bad.” Idealists speak of the eternal poetry of earth, but, Trotsky instructs, “the poetry of earth is not eternal. . . . [M]an in Socialist society will command nature in its entirety, with its grouse and sturgeons.” Human beings will even redesign and improve their own bodies: “The human race will not have ceased to crawl on all fours before God, kings, and capital, in order later to submit humbly before the dark laws of heredity and a blind sexual selection.” People will become stronger, more beautiful, more intelligent. “The average human type will rise to the heights of an Aristotle, a Goethe or a Marx. And above this ridge new peaks will rise.” The effect of such revolutionism was, in fact, unprecedented environmental degradation. During the revolutionary period, it led to the death of millions.

Since liminality cannot go on forever, someone will eventually impose a new everyday reality. Natural and social laws return with a vengeance. Revolutionaries continue to say you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs, but as the economist Aron Katsenelinboigen would reply, we can see the broken eggs—the millions dead—but where is the omelet?

“It turns out,” Zhivago tells Lara, “that those who inspired the revolution aren’t at home in anything except change and turmoil . . . For them, transitional periods, worlds in the making, are an end in themselves . . . they don’t know anything but that . . . they are incompetent. Man is born to live, not to prepare for life. Life itself, the phenomenon of life, the gift of life is so breathtakingly serious! So why substitute this childish harlequinade of immature fantasies, these schoolboy escapades?”

Once a regime is firmly established, the third kind of revolutionism takes hold. We can recognize it by the special kind of blindness it induces. The point is not just that people unwittingly, or even wittingly, close their eyes to every disconfirmation. No, they also make a virtue of the very act of blinding themselves! The ability to do so became a special Bolshevik virtue. In Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry stories, the autobiographical narrator Lyutov struggles to keep his faith in the revolution despite all evidence to the contrary. The soldiers’ constant, and often sincere, use of terms such as treason and counterrevolution to justify unnecessary brutality raises an obvious question: Is it reasonable to expect “wild beasts with principles” to rule with compassion? The question applies even more to professional revolutionaries. Babel’s stories trace the efforts of his fictional counterpart not to see what he sees and to treat his doubts as shortcomings.

Evgenia Ginzburg’s celebrated memoir of life in the Soviet camp system, Into the Whirlwind, is a study in such doubts, and its most terrifying moments are the ones in which the prisoners are shown maintaining faith in the revolution. Even Ginzburg’s fellow prisoner Garey Sagidullin, whose last name had become a famous counterrevolutionary “ism,” insists to her that “I was and I remain a Leninist, I swear by my seventh prison.” Another prisoner needs to confide in someone after the horrors of interrogation and chooses Ginzburg as a fellow lifelong party member: “Sh-sh, Jenny dear, I don’t want the non-communists to hear me, they might get the wrong idea.” Yet another asks Ginzburg for help deciding whether to denounce a prisoner for concealing her jewelry: “It’s disgusting, but on the other hand, this is a Soviet prison and for all I know she may be a real enemy.” “And what about you and me, Katya?” Ginzburg asks, only to get the standard reply, “You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.”

Then there is Julia, who still believes that there really are millions of anti-Soviet agents. “Do you know what’s happening in the country?” she asks. “Treason! Appalling treason which has worked its way into every link of the party and government apparatus.” Ginzburg replies: “But if everyone is supposed to have betrayed one man, isn’t it simpler to think that he has betrayed them?” Julia went pale and said tersely, “I’m sorry, I made a mistake [talking to you].” Ginzburg also recalls her friend Olga, a person of “keen intelligence,” who shared her horror that “whole strata of the population were being ‘removed.’” Only after conversing with her for close to two years did Ginzburg discover, “on our way to [the prison camp] Kolyma . . . that in spite of everything, she worshipped Stalin” and wrote verses praising him. What is the mental mechanism that makes this possible? Ginzburg learns of one such mechanism grounded in Marxist-Leninist thought from “the conscience of the Party,” named Yaroslavsky:

He first explained to me the theory which became popular in 1937 that “when you get down to it, there is no difference between ‘subjective’ and ‘objective.’” Whether you had committed a crime or inadvertently “added grist” to another’s mill, you were equally guilty—even if you had not the slightest idea of what was going on.

Thus, when Ginzburg was accused of participating in Kirov’s assassination and proved that she was not even in Leningrad at the time, that made no difference because she was “objectively” guilty anyway. This makes it possible to know both one’s innocence and the party’s correctness at the same time. Of course, more generally speaking, the concept of “dialectical” reasoning allowed for self-contradiction. There is a famous story about Stalin asking his audience which is worse, the right deviation or the left? After dismissing both answers, he concludes: “both are worse.” It was just such dialectics that suggested George Orwell’s concept of “doublethink.”

Ginzburg describes how, as a dedicated Leninist with unshakeable faith in the party, she gradually began to entertain questions. “For the first time in my life I was faced by the problem of having to think things out for myself.” She was 30 years old, and she had not once thought things out for herself! Moreover, Ginzburg’s depiction of revolutionism and the doublethink it entails is so devastating that her admiring readers have tended to ignore the fact that she never quite frees herself from its coils. She remains a Leninist and retains her faith in the party. For her, the problem is Stalin, and that’s all. The idea that in a one-party state, with no law to restrain whatever the party does, a Stalin is not surprising never occurs to her.

She is also quite aware that according to Leninist doctrine, truth is whatever the party says it is and morality whatever the party finds expedient, while the assertion of any other standards is bourgeois “idealism,” if not “rotten liberalism.” When she tells an interrogator that she just wants to act according to conscience, he asks if she is some sort of Christian. When she replies, no, she just wants to be “honest,” “he gave me a lecture on the Marxist-Leninist view of ethics. ‘Honest’ meant useful to the proletariat and its state.” She never disputes that this is precisely what Leninism entails.

In chapter 39, she is still able to write, “And yet even now, after everything that had happened to us, would we have voted for any regime other than the Soviet, the one that had grown as close to us as our hearts and as natural as breathing? All I had—the thousands of books I had read, the memories of my youth . . . I owe to the revolution.” Does she really think she could not have read those books under the Mensheviks?

In her postscript to the first volume, written after Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization reforms, Ginzburg reaffirmed her unshaken faith in “the great Leninist truth.” How different is she from her friend Julia, who maintained the great Stalinist truth? Ginzburg has been clear that her Leninist beliefs entail her full approval of collectivization as one of the “basic points of the Party line.” Collectivization, of course, included “the liquidation of the kulaks as a class,” followed by the deliberate starvation of millions.

Earlier in the book, while suffering from mortal terror and indignation, Ginzburg exclaims “What d’you think you’re doing to people, to Communists, you devils?” Tellingly, Alexander Tvardovsky, the famed editor of Novy Mir, observed, “She only noticed that there was something wrong when they started jailing Communists. She thought it quite natural when they were exterminating the peasantry.” When her book ends, her affirmation of Leninism sounds to me like the end of 1984. She loved Big Brother.

In Vasily Grossman’s great novel Life and Fate, Krymov, a convinced party man, wonders how all those people who had helped Lenin create the party could have been spies? Krymov realizes that he sincerely believes contradictory things. Can it be, he asks himself, “That I am a man with two consciences? Or that I am two men, each with his own conscience?” This doubling of the conscience, which destroys the integrity of the person, is a crucial aspect of revolutionism.

Krymov also wonders why he and other party members had had nothing to do with the families of arrested comrades, while illiterate old ladies took in their orphans. “Were these old women braver and more honorable than old Bolsheviks?” He arrives at an insight similar to Nadezhda Mandelstam’s: “Fear alone cannot achieve all this. It was the revolutionary cause itself that freed people from morality in the name of morality . . . This was why it was right for a woman—because she had failed to denounce an innocent husband—to be torn away from her children and sent for ten years to a camp. People’s fear of death had been joined with the magic of the Revolution.”

Everyone I have discussed—the Mandelstams, Gershenzon, Pasternak, Trotsky, Babel, Ginzburg, and Grossman—was of Jewish background. Grossman explicitly wonders at how so many Jews became possessed by what he calls “the mystical worship and adoration” of revolution even at those times when the governing ideology demanded the persecution of Jews. This leads one to ask a terrible question: Were Russian Jews especially susceptible to revolutionism and doublethink? Either because of a history of persecution or the continuing resonance of the prophetic tradition? That would be unfortunate because whenever “the magic of revolution” divides the world into the good and the evil, Jews—as Babel notes in his 1920 Diary—will be subject to special violence.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

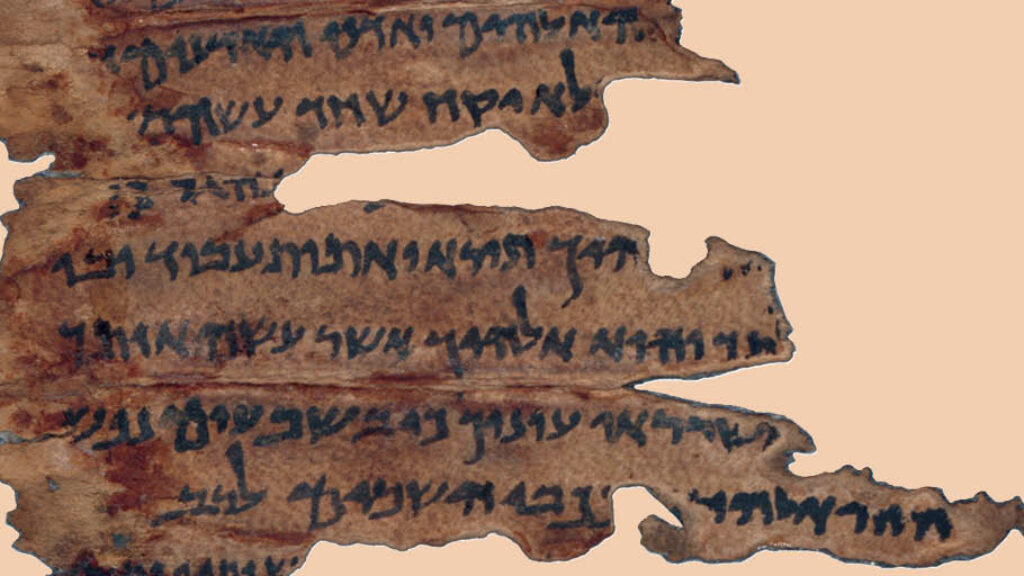

A Torah Exchange: Yonatan Adler Responds to Malka Simkovich

Yonatan Adler Responds to Malka Simkovich's review of his new book, "The Origins of Judaism: An Archeological-Historical Reappraisal

Sephardi Lives: From Ottoman Salonica to Rosario, Argentina

Singing women spark indignation in Salonica, a change of seasons in Argentina requires rabbinic expertise, and Jews in the Ottoman army get fat and happy.

America’s Jewish Bridegroom

Horace Kallen can be found in the ill-starred pantheon of prolific writers known for only one thing: one novel, one sonnet, one treatise, or, in his case, one idea. That idea is “cultural pluralism.”

Happy Is the People Who Knows the Blast

Rabbi Moshe Hayim Efrayim of Sudilkov learned Torah with his grandfather the Ba’al Shem Tov, who later visited him in dreams. In the Degel Machaneh Efrayim, he gave the shofar blast a radical Hasidic meaning.

Shirleyknupp

Astounding, to think that intelligent and educated people can be completely duped into believing such lies simply by desiring a false promise.

konige

Not at all. Intelligence is no proof against insanity, and without wishing to distinguish any particular ethnic group, members of one in particular are not infrequently gifted with unusually strong mental powers, which not infrequently trail off into insanity. History has demonstrated this many times over, and it hasn't gone unnoticed by the rest of the population.