Stirring the Pot

In his response to my essay “In the Melting Pot,” Jack Wertheimer refers to some of the encouraging trends among the non-Orthodox that he explores in detail in The New American Judaism, a surprisingly upbeat book that can give pause even to pessimists like me. He then proceeds to describe—somewhat more emphatically than he does in that volume—the inimical environment within which Jews who commit themselves to their religion must now operate. In view of the overall situation, Wertheimer believes that a great deal of work needs to be done on all fronts to sustain Jewish life in America, from refusing to normalize intermarriage, to mobilizing philanthropic resources more effectively for the benefit of the Jewish community, to strengthening Jewish education.

I am not entirely in agreement with Wertheimer’s assessment of the external threats facing Jews in the United States who wish to affirm their religious identity. For one thing, I am not sure that what he characterizes as elite culture’s hostility to religion is as potent as he seems to believe it is. But I do not wish to engage him on this issue here, since it is a little too remote from the theme of my essay. To his positive recommendations, on the other hand, I have no objections. But I would like to correct him in one respect. I did not call, as he suggests, for a segregated communal life. I did not, in fact, call for anything at all but only indicated what I consider to be the preconditions for Jewish survival. When I said that I could not envision the continued existence, over a long period of time, of any Jewish community that did not have a more or less segregated way of life, I had in mind not so much Kiryas Joel as something like the degree of separation from the rest of the world that Modern Orthodox Jews today, by and large, seem able to maintain. I agree, however, that it is unrealistic to expect that any communities that have moved beyond this kind of separatism will ever revert to it.

Edieal Pinker would not want this to happen, even if it were possible. He wants the Orthodox to be less insular and to assume greater responsibility for the Jewish education of their liberal co-religionists. Of the latter, he reassures us, there will still be in 2043 at least 3.1 million and perhaps more. This reflects some numerical decline, but it is not too discouraging. But what if you look further into the future—as Pinker himself has, together with his colleague Steven M. Cohen? An article that appeared in the Forward in mid-June reports their projection that the “Reform/Conservative community . . . will likely drop from around 3.5 million adherents to a low of 1.5 million adherents over the next eight decades.” And if it remains this strong, it will only be through the large-scale recruitment of “defectors” from Orthodoxy. Despite such losses, Cohen and Pinker argue, the Orthodox will outnumber all other American Jews by the end of the 21st century. These statistics do not, in short, disconfirm my sense of things, nor do they militate in any way against the sort of Orthodox engagement with other Jews that Pinker wishes to see enhanced.

Perhaps Pinker has Erica Brown in mind, either because he knows her or because he has heard about her extraordinary work as a Modern Orthodox educator in the Washington, D.C. area. Not too long ago, I myself read an article in Moment magazine that referred to an informal study group in which she leads such prominent Washingtonians as David Brooks, Jeffrey Goldberg, and David Gregory through Jewish texts. This reminded me of a lecture that Gerson Cohen gave in New York, six years after the graduation speech from which she quotes. Cohen, a great historian of the golden age of Spain, shared with his audience a vision of the Jewish future in the United States that included, at its apex, circles in Washington in which Jewish poets, philosophers, and courtiers—people familiar with the ways of the world but also learned in Hebrew and Judaism—ate, drank, and exchanged ideas about literature and current events in elegant surroundings—just as they had in the Granada of Shmuel Ha-nagid. We may not have anything today that more closely resembles Cohen’s dream than Erica Brown’s classes with important media figures. But to judge from what she has written in response to my essay, they are a far cry from what she usually encounters outside of the Orthodox world. What she says about the charred bottom of the melting pot will stick with me.

Unlike my other respondents, David Biale, for understandable reasons, is unconcerned with religious rejuvenation, but he does identify ways in which contemporary America could inject new vitality into Jewish life. While he does not exactly call the ever-increasing rate of intermarriage a blessing, he suggests that it could both benefit the Jewish “gene pool” and lead to the Jews’ deeper integration into American society. He does this without pointing to any notable deficiencies in our preexisting gene pool or explaining why the integration we had achieved by, say, 1970, when the intermarriage rate was still rather low, was insufficient.

Biale faults me for failing to recognize the impact of the great expansion of Jewish studies on the university level since the time we both entered the field decades ago. While I would agree that this impact is both considerable and, as Biale himself observes, hard to measure, I do not see any reason to think that hundreds of professors transmitting knowledge of Jewish culture to tens of thousands of Jewish (and other) students have significantly altered the overall situation or can do so in the future. For one thing, I doubt that there is anywhere a campus where more than a small minority of Jewish students has taken a significant number of courses in Jewish studies. I suspect, but cannot prove—since there are, as far as I know, no reliable statistics—that on most campuses most Jewish students have taken no such courses or perhaps one. Those who do take courses in Jewish studies usually find themselves in classrooms where the professors properly disavow any attempt to cultivate or alter their students’ Jewish identities. This does not prevent them from inadvertently doing so, of course, but is their impact always positive? Are there not plenty of people teaching about the Jews, and plenty of ways of teaching about them, that are as likely to weaken students’ previous commitments as to nurture them or cultivate new ones?

According to Biale, I have fallen “into the trap of defining an authentic culture as one that involves total immersion” and have therefore failed to take seriously any Jews who define their Jewishness differently from the Orthodox. In response to this charge, I can only say I take such people very seriously. I have written extensively about dozens of them. I just don’t feel that any of them have thus far shown that their individual solutions to what Ahad Ha’am called “the problem of Judaism” provide a usable road map to a Jewish future, in the diaspora, at any rate. I’m not really satisfied by the Orthodox answers, either—but I recognize their power and durability.

In his response to my essay, Biale offers no new recommendations, but he does give voice to a couple of hopes. One is that “globalized” Israelis who reject “ethno-nationalism” and favor a “secular, multicultural Israel” will somehow ally themselves with secular American Jews “to guarantee the future of both.” The other is that the experience of resistance to Donald Trump’s policies will draw American Jews into the kind of solidarity with the downtrodden that will remind them of whom they once were and what authentic “liberal Jewish values” really are, and perhaps galvanize them into becoming standard-bearers of a non-Orthodox American Jewish future.

I think that Biale is pinning one of his hopes on the wrong kind of Israelis. For what is there to inspire people like the ones he describes to reach out to their increasingly distant relatives overseas other than the kind of “ethno-nationalism” that they tend to eschew? It seems to me that they are much more likely to ignore us or to be tempted to come and live alongside American Jews (and to assimilate at least as quickly as we do) than they are to build bridges to us.

Biale’s hope that the current political situation in the United States will energize liberal Jews is more realistic. It is already giving those Jews who see a strong link between their Jewish values and their opposition to Trump a new sense of purpose. But will it inspire more marginally Jewish liberals to reclaim their ethnic identities in the way that some young Jewish revolutionaries in Russia rejoined the Jewish people after the pogroms of 1881–1882? I doubt it. Things would be different, no doubt, if Trump’s program were an anti-Semitic one. But as long as it isn’t, I don’t think that more than a few of the idealists Biale has in mind are going to take Yiddish classes in the evening, to say nothing of heading back to shul. I think Biale is grasping at straws.

Missed the earlier items in this symposium? Start with Allan Arkush’s original piece, then look at responses from four leading Jewish thinkers:

- Jack Wertheimer, whose new book is the occasion for Arkush’s piece

- David Biale, whose work figures in Arkush’s essay

- Edieal Pinker, who weighs in with a new statistical analysis

- Erica Brown, who speaks movingly about the charred remains of Jewish culture that cling to the bottom of the American melting pot

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Swimming in an Inky Sea

Ilana Kurshan, a hyper-literary, ideologically egalitarian, hopeless romantic (in her words), doesn’t fit the typical profile of a Daf Yomi participant.

Leviticus on the Fourth of July

Biblical narratives and imagery have played a surprisingly large, even outsized, role in the formation of the American national consciousness and institutions.

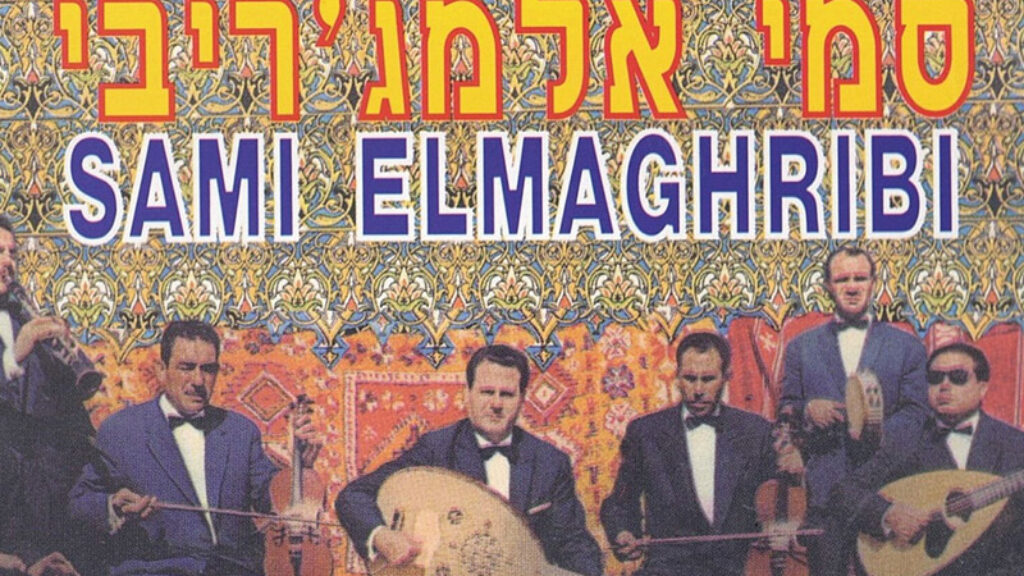

Missing Notes

There was a time when Jewish artists set the tone for North African music, but now only echoes remain.

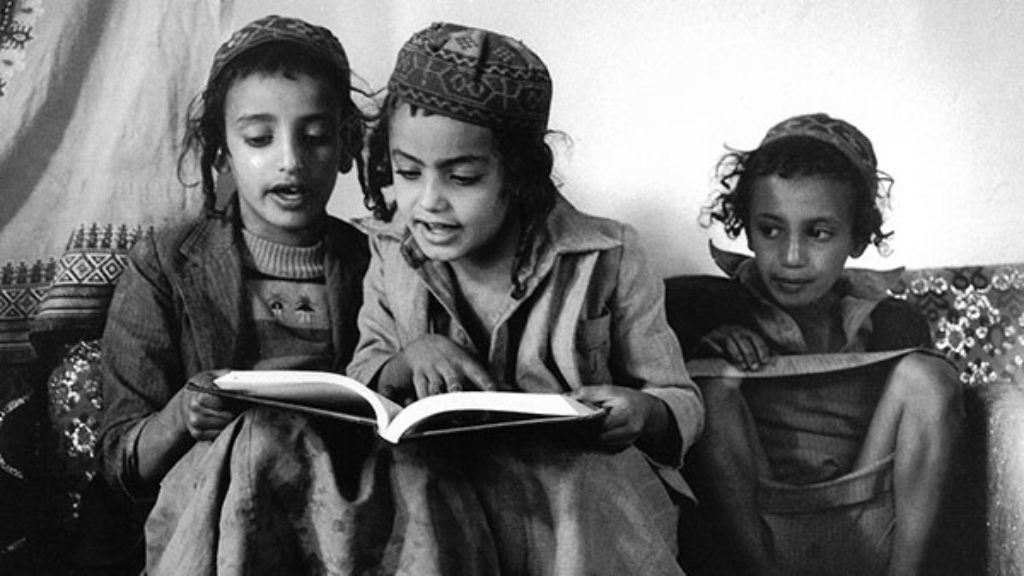

Visiting Yemen in the 1980s: A Photo Essay

"Sometimes one really does find that moment and the image seems to capture a person—this particular Jew, this particular way of life—but often one does not and feels the need to return, to try again." But in this case, there are no Jewish communities in Yemen to return to.

Andrew Gow

The reality in specific shuls may actually look different from the aggregate stats. In my community, I see a growing population of younger people who identify as Jewish and who are, by the standards of Conservative Judaism, halachically Jewish, either through maternal descent or through conversion. In my shul, there are as many kids of mixed origin as of maternal-AND-paternal Jewish origin, and perhaps a third of the former, in turn, are people of colour. In 30 years, my shul's membership might be smaller, but it will definitely be much more ethnically and culturally diverse. Only by welcoming the intermarried have we staved off the collapse of shul membership that would otherwise have happened already. Do these newcomers "dilute" Judaism? Well, that depends on which parts of Judaism one is discussing. Yes, many are growing up without much knowledge of traditional observance. But they are committed to Judaism as a "religion", and they will probably continue to be so, but rarely if ever eat a single item of Ashkenazi cuisine, and keep kosher only in the most notional of ways (if at all). They are becoming a different kind of Jews, protestantiform Jews, if you will. Their descendants will probably continue to practice this non-immersive form of Judaism, immersed in the surrounding culture but also always somewhat different from it. Eventually, Orthodox Jews may come to see and define them as not properly Jewish, and place them in the same category as Karaites or Samaritans, as is already happening regarding Reform Jews. Meanwhile, the mixed-origin and "protestantiform" Jews I know retain much more of Jewish practice (and arguably of Jewish values) than secular Israelis. They are more similar, oddly, to Mizrahi and Sfardi shomrei masoret than they are to hiloni of Ashkenazi descent. This is an odd coincidence, since many in both groups are people of colour.