It’s Spring Again

As everyone knows, April is the cruelest month, though even English majors sometimes forget why the poet said so. What’s wrong with lilacs coming out of the dead land? Something to do with a then-repressed Christianity and a bad marriage (or vice versa), a disinclination to have the spring rain stir dull roots, or anything else. Although, like Joseph Epstein in these pages, and Edward Mendelson in some others, I am inclined to think that after the Holocaust, T.S. Eliot mostly repented of his anti-Semitism, I still prefer Cole Porter (“I love you/Hums an April breeze”).

Of course, the specifically Christian backdrop of Eliot’s lines is the New Testament account of Jesus’ resurrection in springtime. Curiously, when, 50 or so lines later, Eliot gets to the famous tarot card stanza, “the hanged man” card is supposed to represent Jesus, along with Frazer’s pagan man-god, who must be slain and replaced so that the world can be renewed. I suppose that it is just a coincidence that the rabbis’ old polemical description of Jesus was “the hanged one.”

The backdrop, in turn, of the Christian belief in resurrection is not merely, or mainly, pagan. It is a central, and unsettling, dogma of rabbinic Judaism that, as the second blessing of the Shemoneh Esrei states, God “sustains the living with kindness and revives the dead with great mercy.” At the end of this blessing, there is even a whiff of spring: “Who is like you, lord of power, and who is similar to you, O King, who brings death and revives life, and causes salvation to sprout,” which sounds a little like the return of those lilacs that Eliot dreaded.

The connection between springtime and the messianic resurrection of the dead is even clearer in the haftarah for the Sabbath that falls in the middle of Passover. The prophetic reading the rabbis chose is Ezekiel’s vision of the revival of the dry bones:

I prophesied as I had been commanded. And while I was prophesying, suddenly there was a sound of rattling, and the bones came together, bone matching bone. I looked and there were sinews on them, and flesh had grown, and skin had formed over them; but there was no breath in them. Then he said to me, “Prophesy, O mortal! Say to the breath: thus said the LORD God: Come, O breath, from the four winds, and breathe into these slain, that they may live again.” I prophesied as He commanded me. The breath entered them, and they came to life and stood up on their feet, a vast multitude. (Ezekiel 37: 7–10)

A startling painting on the walls of the ancient synagogue at Dura Europos depicts this scene. There one finds some 2nd-century Jews who have, until recently, been dead and who look very surprised to have been reconstituted and revived. Alongside them are various body parts—heads, arms, legs—that have yet to be re-membered, as it were. (ISIS has apparently looted the original archaeological site of Dura Europos near the Euphrates, but the paintings remain, at least for now, in the National Museum of Damascus.)

Of course, the plain meaning of Ezekiel’s vision is that it is an allegory, indeed one that God himself interprets:

And He said to me, “O mortal, these bones are the whole House of Israel. They say, ‘Our bones are dried up, our hope is gone; we are doomed.’ Prophesy, therefore, and say to them: Thus said the LORD God: I am going to open your graves and lift you out of the graves, O My people, and bring you to the land of Israel.” (Ezekiel 37: 11–13)

This prophecy of national renewal is, of course, why Chapter 37 of Ezekiel was chosen to read on Passover. And yet, as Jon D. Levenson showed in his Resurrection and the Restoration of Israel, the promise of Israel’s revival was not held entirely distinct from the promise of an actual revival of the dead at the end of times.

Certainly, by the early rabbinic period, when the Dura Europos synagogue was built, resurrection of the dead was a literal belief. Rabbi Yochanan, who lived in the 3rd century, requested that he be buried in clothes that were neither black nor white, since he didn’t know whether he would be standing with the righteous or the wicked at the final judgment after his resurrection. When the Talmud speaks of “the world to come” (olam ha-ba) it is an interesting question as to whether it was generally referring to the eschatological world Rabbi Yochanan anticipated or the kind of disembodied afterlife with whose conception we are now more familiar.

Reading bound proofs of Don DeLillo’s Zero K, forthcoming this spring, got me thinking about resurrection. The novel is about a damaged, diffident middle-aged man named Jeffrey whose father, Ross Lockhart, is a world-bestriding billionaire. Lockhart funds a secret compound where, to quote Scribner’s copy, “death is exquisitely controlled and bodies are preserved until a future time when biomedical advances and new technologies can return them to a life of transcendent promise.”

The compound, with its “blind buildings, hushed and somber, invisibly windowed,” in an undisclosed desert location is somewhere between Google headquarters and the secret desert lair of a Bond villain. Its inhabitants (who include a depressed monk and a philosophical Jew named Ben Ezra, though this is really an allusion to the famous Browning poem) are somewhere between fellows of a think tank, say the Santa Fe Rand-Hartman Institute, and New Age cultists. Lockhart’s younger second wife Artis has terminal cancer and is preparing to die, or rather to enter a technologically controlled limbo between life and death while awaiting revival. Ross has brought a skeptical Jeffrey here to say goodbye to his stepmother, and perhaps to him as well.

“The body will be frozen. Cryonic suspension,” he said.

“Then at some future time.”

“Yes. The time will come when there are ways to counteract the circumstances that led to the end. Mind and body are restored, returned to life.”

“This is not a new idea. Am I right?”

“This is not a new idea. It is an idea,” he said, “that is now approaching full realization.”

Jeffrey’s question is about earlier crackpot versions of cryonics (“‘People enroll their pets,’ I said.”), but DeLillo is well aware of the ancient resonance of this idea. His father says:

“Faith-based technology. That’s what it is. Another god. Not so different, it turns out, from some of the earlier ones. Except that it’s real, it’s true, it delivers.”

“Life after death.”

“Eventually, yes.”

“The Convergence.”

“Yes.”

“The Convergence” sounds like DeLillo’s version of futurologist Ray Kurzweil’s “Singularity,” when, in the very near future, we will transcend “our version 1.0 biological bodies.”

DeLillo has always had an apocalyptic streak (“Everybody wants to own the end of the world” are the italicized first words of the novel), but what interests me more is his attempt to think through what it would really mean for a person to imagine, hope, and plan for an actual bodily resurrection. One of the compound’s philosophico-scientific gurus is speaking:

“The dormants in their capsules, their pods. Those now and those to come.”

“Are they actually dead? Can we call them dead?”

“Death is a cultural artifact, not a strict determination of what is humanly inevitable.”

. . . “We will colonize their bodies with nanobots.”

“Refresh their organs, regenerate their systems.”

It is to believe that one—at least if one is a billionaire—need never succumb to that final winter, that it will be possible for memory, technology, and desire to stir those dull human roots (“Enzymes, proteins, nucleotides”) with spring rain and revive the dead.

On the whole, the life after death of Zero K is a real resurrection, a promise that revived bodies will emerge from their capsules; it is an Ezekiel-Kurzweilian vision. However, like the actual futurologists, whom DeLillo has apparently studied closely, his characters sometimes offer a different vision of human life 2.0. This is a vision of a disembodied mind that can be downloaded and preserved in any number of substrates; as long as the software and content are preserved, the hard—or wet—ware is a matter of indifference. The tension between these ideas, the world to come in which we have and need our bodies and the world to come in which we don’t, is also not new.

It was, in fact, the distinction between an embodied and a disembodied afterlife that animated one of the greatest theological controversies of medieval Judaism. In his Commentary to the Mishnah, Maimonides included the resurrection of the dead as one of the 13 principles of faith. But his purely spiritual account of the world to come, where, to quote one of his favorite talmudic passages, “there is no eating and no drinking . . . and the righteous . . . bask in the radiance of the Shekhina,” seemed to make such a resurrection pointless. If one is already a bodiless spirit communing with the divine intellect in an endless seminar on physics and metaphysics, and this is the summit of human attainment, why would one want to be re-encumbered with a body? And how could one’s body be revived anyway, given Maimonides’ scientific assertion that

decay and decomposition are natural and inevitable processes?

Maimonides had an answer for this, albeit one that was unsatisfying and arguably insincere (at least his opponents thought so). An omnipotent God, who can perform miracles, can and will revive the dead in the messianic era, because He promised that He would do so. But then they will die again and return to their superior bodiless existence. In short, spring will return one final glorious time, and then disappear forever. If Maimonides had walked into the Dura Europos synagogue, he probably would have walked right back out again.

Of course, such an austere vision of the afterlife would be wintry comfort for Ross and Artis Lockhart, who, for all their hubris, simply do not want to lose—and can’t really imagine losing—their bodies, and hence their selves.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Idea of Abrahamic Religions: A Qualified Dissent

What is "Abrahamic" about Judaism, Christianity, and Islam?

Yiddish Genius in America

The great Yiddish poet Jacob Glatstein wrote two autobiographical novels and envisioned a third, set in America. Why didn’t he write it?

One State?

Sari Nusseibeh's recent book is a new formulation of an old proposal.

Indispensable Man

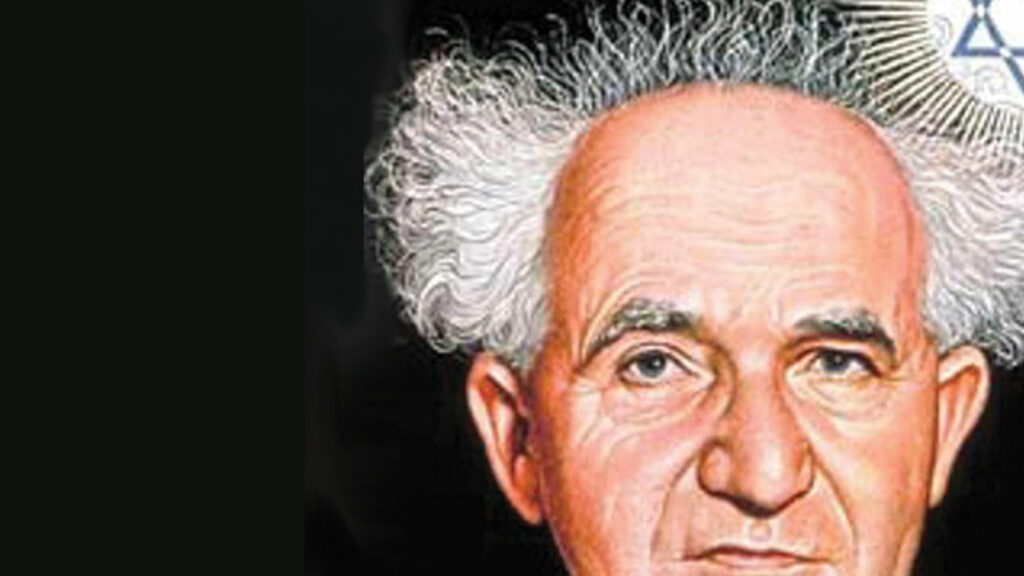

In his effort to cut David Ben-Gurion down to size, Tom Segev blames him for failures that were not his and gives him insufficient credit for his achievements. A closer examination of the historical record reveals a greater man than the one Segev attempts to dissect.

David Z

I find the Dura Europa painting fascinating for the clothing alone. It appears to my untrsined eye medieval European. Not sue what I thought Second Century Syrian Jews wore, but not that...

Also ironic that it is in ISIL hands. The assortment of limbs and heads seems a post-ISIL happening. I wonder how usual it was for people to be buried dismembered like that.

grigalem

@David Z

First of all the painting is not in ISIS's hands. Learn to read.

Second, I don't think you have a clue what "irony" means.