Red Rosa

In the second half of the 19th century, the Polish town of Zamosc produced two of the most extraordinary Jewish personalities of the age. The first was I.L. Peretz, the great Yiddish writer, best known to many readers for his bitter story “Bontshe the Silent.” In that tale, Bontshe is a modern anti-Job, a humble Jew who suffers an endless series of injuries and humiliations, but never raises his voice against God. When he dies and goes to heaven, even the prosecuting angel can find nothing to say against him, and the judge promises to give him anything he might desire. But all Bontshe can think to ask for is a hot buttered roll—whereupon the angels “hang their heads in shame at this unending meekness they have created on Earth.” Even in death, Peretz implies, Bontshe can’t grasp the lesson that the judge imparts: “You never understood that you need not have been silent, that you could have cried out and that your outcries would have brought down the world itself and ended it.”

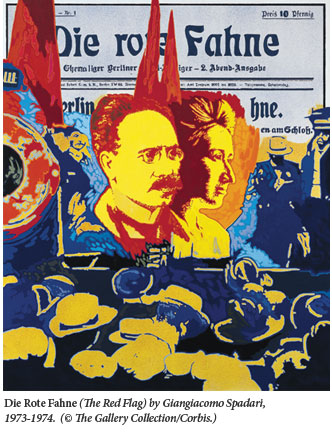

If there is one reader who might have agreed wholeheartedly with this critique of passivity, who would have understood the right of the poor to cry out and remake the world, it was the other famous scion of Zamosc, Rosa Luxemburg. Starting as a teenager, Luxemburg devoted her whole life to overthrowing capitalism in Europe. As a theoretician, orator, and activist, she rose to a leading position in the socialist parties of Poland and Germany, and came to embody the hope—and, to her opponents, the dread—of Marxist revolution. To Lenin, whom she admired and criticized, she was “the eagle of the revolution”; to the German right, she was “Red Rosa,” an anti-Semitic hate figure, good for frightening children. Her legend was sealed in January 1919, when she and Karl Liebknecht, her fellow leader of the radical-left Spartacus League, were assassinated by right-wing soldiers, with the connivance of Germany’s nominally socialist government.

To Hannah Arendt, who was greatly influenced by Luxemburg, her murder was “the watershed between two eras in Germany; and it became the point of no return for the German left.” With her death, it seemed in retrospect, the possibility of a humane and democratic communism in Germany was foreclosed. Indeed, from that day to this, whenever people want to rehabilitate communism from its legacy of dictatorship and mass murder, they are drawn to Luxemburg as a symbol of the path not taken. Thus Trotsky—who never got along with Luxemburg in her lifetime, perhaps because they were too similar—declared that his Fourth International, the organization he founded to combat Stalinism, would fight “under the sign of the three Ls”—Lenin, Luxemburg, and Liebknecht. After World War II, an influential group of anti-Soviet French Marxists named themselves “Socialism or Barbarism,” after a slogan used by Rosa Luxemburg in a pamphlet attacking World War I. She was a natural favorite of the New Left in the 1960s. Today, Germany’s Left Party, the organizational descendant of East Germany’s Communist Party, has an educational wing named the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. For PR purposes, this is a much better name from the German Communist past than, say, Walter Ulbricht.

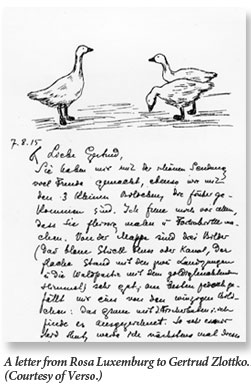

The Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung is now helping to produce a complete, 14-volume English edition of Luxemburg’s writings, of which The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg is the first installment. The book is not actually a comprehensive collected letters—that will apparently come later, and take up several volumes. Rather, The Letters is a compact introduction to Rosa Luxemburg, which, in the words of the editor Peter Hudis, “brings to life the depth and breadth of Luxemburg’s political and theoretical contributions as well as her original personality.”

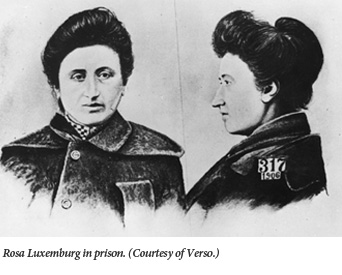

In approaching Luxemburg through her private correspondence, rather than through her economic works like The Accumulation of Capital or her numerous articles and speeches, the editors of The Letters are continuing an old tradition. Luxemburg’s posthumous legend began to take shape in 1920, with the publication of Briefe an Freunde (“Letters to a Friend”). This small book consisted of 22 letters written to Sophie Liebknecht, Karl’s wife, during the years 1916-1918, which Luxemburg spent in prison as an anti-war agitator. “Whoever knows only Rosa Luxemburg the fighter and the scholarly author,” the publisher claimed at the time, “does not yet know all sides of her.” These letters revealed the inner Rosa, “the richness of the inexhaustible wellsprings of her heart.”

Many of those letters to Sophie Liebknecht are included in the new Letters, and they go a long way toward explaining the reverence in which Luxemburg continues to be held by so many. Shut up in virtual isolation, physically ill, spiritually devastated by a world war that had destroyed Germany’s socialist movement, Luxemburg finds courage and love in the little glimpses of nature she is allowed:

What I see from my window is the men’s prison, the usual gloomy building of red brick. But looking diagonally, I can see above the prison wall the green treetops of some kind of park. One of them is a tall black poplar, which I can hear rustling when the wind blows hard; and there is a row of ash trees, much lighter in color, and covered with yellow clusters of seedpods (later they will be dark brown). The windows look to the northwest, so that I often see splendid sunsets, and you know how the sight of rose-tinted clouds can carry me away from everything and make up for all else.

Luxemburg’s letters from prison are, in fact, so resolutely cheerful and gentle that they can become cloying. There is a solemn whimsy in her devotion to animals, for instance, that puts the contemporary reader helplessly in mind of Disney cartoons: “Recently I sang the Countess’ aria from Figaro, about six [titmice] were perched there on a bush in front of the window and listened without moving all the way to the end; it was a very funny sight to see.” Yet coming from “Red Rosa,” this kind of thing struck the first readers of her letters with the force of a revelation. Here was a revolutionary who loved flowers and birds, and Hugo Wolf’s Lieder, and the poems of Goethe. This Luxemburg offers the strongest possible contrast with Lenin, who famously said, “I can’t listen to music too often . . . it makes you want to say stupid nice things, and stroke the heads of people who could create such beauty while living in this vile hell. And now you must not stroke anyone’s head: you might get your hand bitten off. You have to strike them on the head, without any mercy.”

Gender surely plays a role in the idealization of Luxemburg. Though she never had children, she was often maternal about animals—above all, her cat Mimi, which she doted on. (“Poor Mimi . . . impressed Lenin tremendously,” she writes after a visit in 1911. “She also flirted with him, rolled on her back and behaved enticingly toward him, but when he tried to approach her she whacked him with a paw and snarled like a tiger.”) Indeed, her tenderness towards animals can sound like another face of her compassion for the poor and oppressed. The connection is almost explicit in a letter she wrote to Sophie in December 1917, describing the arrival at her prison of a military wagon pulled by water buffaloes:

The soldier accompanying the wagon, a brutal fellow, began flailing at the animals so fiercely with the blunt end of the whip handle that the attendant on duty indignantly took him to task, asking him: Had he no pity for the animals? “No one has pity for us humans,” he answered with an evil smile, and started in again, beating them harder than ever . . . [the buffalo had] precisely the expression of a child that has been punished and doesn’t know why or what for . . . No one can flinch more painfully on behalf of a beloved brother than I flinched in my helplessness over this mute suffering.

Reading The Letters, however, it becomes clear that Luxemburg would have been hugely, and rightly, offended to be thought of as merely compassionate. That mute buffalo might be her version of Bontshe the Silent, but she herself was anything but meek. On the contrary, she was more like Peretz’s judge, urging the workers of the world to turn it upside down.

As it happens, Peretz makes one fleeting, and highly revealing, appearance in the biography of Luxemburg by Elzbieta Ettinger. A Polish socialist named Radwanski paid a visit to Luxemburg, and mentioned that he had taught himself Yiddish in order to communicate with the Jewish workers. Her response was furious: “Here is another madman, another goy who learned the Yiddish jargon.” This led to a denunciation of “literature in jargon,” and in particular “Peretz, that lunatic, who has the temerity to insult Heine with translation from the beautiful German language to that old-Swabian dialect, corrupted by a smattering of Hebrew words and garbled vernacular Polish.”

This disdain for Yiddish as a “jargon” was typical of the educated Jewish bourgeoisie of Luxemburg’s generation. She was born in 1871 as Rozalia Luksenburg, the youngest daughter of an assimilated Jewish family. Her mother, Lina Loewenstein, could allegedly trace her family line through seventeen generations of rabbis, all the way back to the 12th-century commentator Zerachya Halevi. But Lina’s sacred texts were Goethe and Schiller, and the children were raised speaking Polish, not Yiddish. In Warsaw, where the family moved when she was two years old, Rosa attended a Russian-language gymnasium.

Already as a young girl, Luxemburg was involved in underground socialist politics. She once chided the ten-year-old daughter of a comrade, “At your age I didn’t play with dolls, I made the revolution.” This may have been an exaggeration, but only a slight one: she was only eighteen when she had to flee Poland to escape arrest. (The story goes that she won over the border guard by saying that she was running away from her family, who were trying to prevent her from converting to Catholicism.) From 1889 until the end of her life, Luxemburg lived in exile—first in Switzerland, where she helped found a small Marxist party called the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL), then in Germany, where she became a leader of the much bigger and more influential Social Democratic Party (SPD).

The Letters offers a wonderfully intimate view of Luxemburg as a young intellectual and politician on the rise. In her ambitions and hesitations, she could be any young man or woman from the provinces, newly arrived in the big city. In 1898, writing to Leo Jogiches, her lover and fellow SDKPiL leader, Luxemburg boasted of her triumphs in socialist Berlin:

Incidentally, I’m making a very big impression here—at least on my landlady—and what is most astonishing, everyone sees me as being extraordinarily young, and they’re amazed that I’m already so mature . . . I feel as though I have arrived here as a complete stranger and all alone, to “conquer Berlin,” and having laid eyes on it, I now feel anxious in the face of its cold power, completely indifferent to me.

The anxiety she kept to herself; it was her preternatural confidence that impressed the leaders of the SPD. Young, foreign, and female, still uneasy with the German language, Luxemburg made her name with blistering articles in the Party press and speeches at Party congresses. From the beginning, she fought for the two principles that defined her political creed. The first was her commitment to revolution, which put her at odds with the reformist tendencies in the rather staid SPD. In a series of articles, she savaged Eduard Bernstein, the “revisionist” socialist who argued that reforming capitalism was more important than overthrowing it. History, Luxemburg remained certain to the end, was on the side of the workers’ revolution—even though the revolution, like the Messiah, kept on not coming. Her very last article, published in January 1919 after the failure of the Spartacus uprising in Berlin, declared: “The whole road of socialism—so far as revolutionary struggles are concerned—is paved with nothing but thunderous defeats. Yet, at the same time, history marches inexorably, step by step, toward final victory!”

Luxemburg’s second principle, a corollary of the first, was that class always trumped nation as a political force. Nationalism, she insisted, was a purely bourgeois ideology, which the proletariat could never really share; the workers’ only loyalty was to the international working class. This belief pitted the SKDPiL against the much more popular Polish Socialist Party (PPS), which combined socialism with a commitment to the independence of Poland. Luxemburg’s doctoral thesis, The Industrial Development of Poland, used economics to argue that Polish independence was actually impossible, thanks to the interdependence of the Polish and Russian economies. “The struggle for the restoration of Poland [is] hopelessly utopian,” she wrote in 1905. The only solution to Polish problems was “a socialist system that, by abolishing class oppression, would do away with all forms of oppression, including national, once and for all.”

It did not escape anyone’s notice that Luxemburg, like Jogiches and most of the other leading figures in the SDKPiL, was Jewish, or that this might have something to do with her and their failure to share in the national aspirations of most Poles. In The Letters, it’s possible to trace the fallout of an especially vicious campaign that was launched against her in 1910, when a Polish newspaper used obscene anti-Semitic rhetoric to discredit the SDKPiL. Luxemburg’s party, the paper said, was “tied by race and family to the rest of the Jews; these purely anthropological ties are so strong that anyone who dares to question the ideology of any Jew is immediately confronted by an alliance of a Talmud Jew, a socialist Jew, and a liberal Jew.”

In response, Luxemburg solicited letters of support from leading Western European socialists. Writing to a Belgian party leader, she explains, “the entire liberal, progressive press has abandoned itself to an all-out orgy of anti-Semitism . . . As you see, it is a Dreyfus case in miniature.” Yet in the articles Luxemburg herself wrote about the Dreyfus Affair, it is striking how consistently she refused to view the case in Jewish terms. In an 1899 article about the Affair, for instance, she describes “militarism, chauvinism-nationalism, anti-Semitism, and clericalism” as “direct enemies of the socialist proletariat.” Even explicit anti-Semitism, it appears, cannot really be directed against the Jews, only against the proletariat; class, not nation or religion, is the only genuine reality. (The editors of The Letters comically share this willed blindness: a footnote explaining the Dreyfus Affair does not use the word “Jewish” even once, and defines the anti-Dreyfusards simply as the “chauvinistic camp of reaction backed by the big bourgeoisie.”)

To read The Letters closely, in fact, is to see how dramatically wrong the anti-Semitic slander against Luxemburg was. Not only did she not represent a secret alliance between religious, liberal, and radical Jews, she was actually much more hostile to Jewishness, in any form, than she was to other expressions of nationhood, especially Polish ones. Writing to Jogiches about a visit to Upper Silesia in 1898, she rhapsodizes about Poland in terms that are anything but scientifically Marxist:

The surroundings here have made the strongest and most emphatic impression: cornfields, meadows, woods, broad expanses, and Polish speech and Polish peasants all around. You have no idea how happy it all makes me. I feel as though I’ve been born anew, as though I have the ground under my feet again. I can’t get enough of listening to them speak, and I can’t breathe in enough of the air here!

Compare her reaction to “Polish speech” with her reaction to “Yiddish jargon,” and you can gauge Luxemburg’s profound discomfort with everything Jewish. This hostility crops up again and again in The Letters. For instance, when she visits a resort in 1904, her pleasure at encountering “a genuine [party] comrade, a living and breathing one from Berlin,” turns to pain when she discovers that “unfortunately, he was also an even closer comrade in the sense of the faith of our fathers.” (“In such cases our forefathers’ custom would have been to utter a brief mazel tov,” she adds wryly.)

This disdain had political consequences as well as personal ones. Early on, when Luxemburg’s SDKPiL was a minor party whose leaders were mostly in exile, the Jewish Bund was one of the biggest socialist parties in Eastern Europe. Other Russian and Polish party leaders wanted to make an accommodation with the Bundists; Luxemburg disagreed, in accordance with her internationalist views. But there is more than principle at work in her unusually abusive descriptions of Bund leaders as “rabble” and “the shabbiest of political horsetraders.” That last word, the editors of The Letters note, is a translation of “Schacherpolitiker,” but they don’t explain that schacher was a word with strong anti-Semitic connotations, and had been used as such by Marx in his notorious essay “On the Jewish Question.”

Luxemburg’s fullest statement on the Bund comes in a letter to a Polish comrade in 1901:

Well, now, to put it briefly, this entire “Bund” . . . what they deserve at the least is to have any upstanding, respectable person throw them down the stairs the minute they open the door (and for this purpose it is best to live on the fourth floor) . . . they are individuals who are made up of two elements: stupidity and cunning. They are incapable of speaking two words to anyone without having the concealed intention of robbing them (in a moral sense).

Luxemburg’s political career was defined, in large part, by her struggle against the PPS, but she never writes about the Polish socialists in such venomously personal terms. It is unmistakable that Jewishness—even in the anti-Zionist form of the Bund’s Jewish socialism—provoked in Luxemburg a visceral need to disassociate herself. Seen in this light, there is something more than simple humanitarianism at work in the famous lines she wrote from prison in 1917:

What do you want with this theme of the “special suffering of the Jews”? I am just as much concerned with the poor victims on the rubber plantations of Putumayo, the Blacks in Africa with whose corpses the Europeans play catch . . . Oh that “sublime stillness of eternity,” in which so many cries of anguish have faded away unheard, they resound within me so strongly that I have no special place in my heart for the [Jewish] ghetto. I feel at home in the entire world, wherever there are clouds and birds and human tears.”

The crowning irony is that these lines were addressed to Mathilde Wurm, who was Jewish, as were almost all of Luxemburg’s closest friends and party comrades: Leo Jogiches, and her later, younger lover Kostya Zetkin, and Luise Kautsky, and Sophie Liebknecht, and on and on.

According to Arendt, writing about Luxemburg’s “peer group” in Men in Dark Times, “these Jews . . . stood outside all social ranks, Jewish or non-Jewish, hence had no conventional prejudices whatsoever, and had developed, in this truly splendid isolation, their own code of honor.” Even today, there are many Jews who admire this definition of Jewishness as a universal humanism, which prides itself on indifference to specifically Jewish interests. But The Letters lends less support to Arendt’s view of Luxemburg than to the view of J.L. Talmon, who wrote that Luxemburg’s “all-pervasive revolutionary internationalism appears to me an expression of the Jewish malaise of an outsider.”

More, it represents a failure of empiricism—an inability to reckon with the factors that shape political and psychological reality, for Jews and non-Jews alike. This failure exacted a large toll on Luxemburg’s political work, and falsified her hopeful prophecies. She viewed the Eastern European proletariat in wholly idealized Marxist terms: “The highest idealism in the interest of the collectivity, the strictest self-discipline, the truest public spirit of the masses are the moral foundations of socialist society, just as stupidity, egotism, and corruption are the moral foundations of capitalist society.”

But this was the common people as it should be, not as it was. One might say that Luxemburg failed to connect her proletarian ideal with the real soldier she saw whipping a helpless buffalo—a man brutalized by the war that was supposed to have radicalized him. The same mistake is what allowed her to tell Sophie Liebknecht, in late 1917, that the Russian Revolution could not possibly be dangerous for the Jews: “As far as pogroms against Jews are concerned, all rumors of that kind are directly fabricated. In Russia the time of pogroms has passed once and for all. The strength of the workers and of socialism there is much too strong for that. The revolution has cleared the air so much of miasmas and stuffy atmosphere of reaction that a new Kishinev has become forever passé. I can sooner imagine pogroms against Jews here in Germany.” She was half right.

Suggested Reading

Lost Music

Jeffrey M. Green, Aharon Appelfeld’s translator for more than 30 years, remembers the beloved Israeli novelist.

Unfinished Rock

Why is the last stanza of Ma'oz Tzur unlike all other stanzas?

Summer of ’36

By 1936, Joseph Roth’s alcoholism was increasingly desperate, and his friendship with Stefan Zweig was frayed. But still that summer gave them an opportunity to recover something of their old friendship.

The Rebbe and the Professor

After the war, the great Jewish historian Salo Baron wrote to Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, for help with his work on the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction. As Hannah Arendt suggested in a side note to Baron, the commission probably wasn't “kosher” enough for Schneersohn, but their exchange illuminates a dark historical moment.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In