The Secrets of the Efod

A century and a year before the expulsion of 1492, the Jews of Christian Spain had to contend with a less famous catastrophe. An unexpected explosion of popular anti-Jewish violence left thousands dead and whole communities destroyed. It also produced a novel subgroup within Spanish society comprising Jews who saved themselves from Christian mobs by accepting baptism. Among these conversos was the scholar, physician, and moneylender Isaac ben Moses, also known as Profayt Duran Halevi, who lived in the small Jewish community of Perpignan in northernmost Catalonia. Following his baptism in 1391 or perhaps early 1392, Duran took on the name of Honoratus de Bonafide—in public. But in private he continued to write in Hebrew under the pen name Efod.

As Maud Kozodoy explains in her well-conceived and skillfully wrought new book, the acronym Efod comes from the first letter of amar (said) and the initials of the author’s pre-conversion name, Profayt—since in Hebrew peh and feh are vocalizations of the same letter—Duran. This was the way Duran had always signed his marginal glosses, but in Hebrew efod is also the name for a garment worn by the high priest that had been associated in some rabbinic sayings with atonement for the sin of idolatry. As Kozodoy shrewdly remarks, the name Efod was itself such a “symbolic garment” for Duran. Under this name, he issued a series of Hebrew writings, including two anti-Christian polemics, in the dozen or so years following his conversion.

Kozodoy aims to solve what she takes to be the main puzzle of Duran’s life: “how to understand his literary production in the context of his forced baptism.” How did it happen, for instance, that some of the most brilliant anti-Christian polemics of the late Middle Ages were written by an (at least public) Christian? As her book’s subtitle indicates, she tackles such questions through recourse to the familiar category of identity, but not in any sort of faddish way. Secret Faith is a work of meticulous archive-based biography and cross-disciplinary intellectual history. Duran was a polymath whose interests included mathematics, astronomy, astrology, medicine, philosophy, Hebrew language, biblical exegesis, and, of course, anti-Christian polemics. This imposes considerable demands on a scholar, and Kozodoy does not shrink from them, even when a plunge into technical specifics is required, as in the case of Duran’s treatise on the Jewish calendar, replete as it is with “epicycles,” “eccentrics,” and more.

Kozodoy rightly lays stress on Duran’s rationalism as a key not only to his intellectual personality but religious identity. She describes some of his conventional Maimonidean allegiances and devotes a short chapter to Duran’s commentary on The Guide of the Perplexed. Along with many of his intellectual contemporaries, Duran did not, however, follow Maimonides in his famous denigration of “stupid astrologers.” Indeed, not long after his baptism, he became a court astrologer to Joan I of Aragon—the previous holder of this position, a Jew, having died in the riots that brought about Duran’s conversion. Kozodoy suggests, on the evidence of his writings, that Duran’s rationalism buttressed his Jewish pride and fortified his ongoing allegiance to Judaism after his conversion. Indeed, he seems to have identified rationality with Judaism, and she shows how this conviction informed what are by far Duran’s most daring works: two brilliant and innovative polemics in which he subjected Christianity to theological ridicule and an exacting historical critique.

Duran wrote the first of his anti-Christian books about three years after his conversion. It takes the form of an epistle addressed to one of his contemporaries who was a genuine Jewish convert to Christianity. Here the innovation lies not so much in the work’s contents but in its form, especially the “barbed biblical allusion[s]” with which Duran pointed out the folly of an educated Sephardi Jew abandoning a faith in harmony with reason to embrace one at odds with it. Nearly all sections of the “letter” begin with the ironic address that came to serve as its title, Al Tehi Ke-avotekha (Be Not Like Your Fathers). In each, Duran continues in this ironic vein, showering praise on his addressee’s abandonment of the religion of his ancestors while in fact condemning it. In contextualizing this work, Kozodoy adds yet another layer of irony, cautiously but plausibly suggesting that Duran’s literary models for this work were, in fact, Christian.

In his second polemical work, Kelimmat Ha-goyim (Shame of the Gentiles), Duran approaches contentious issues in the medieval Jewish-Christian debate in another novel way, this time methodological. To undermine contemporary Catholicism, he distinguishes between the original teachings of the primitive church as reflected in the New Testament and exegetical misrepresentations and theological distortions of them propounded in later patristic and medieval literature. He observes, for instance, that when Jesus spoke poetically, as was his wont, he said that he and his Father were one, by which he meant only that he had a special relationship with God. Misunderstanding their own scriptures, Duran explains, later Christians deified him.

Kozodoy’s investigation of this work is illuminating, but not entirely satisfying. As is the case with Al Tehi Ke-avotekha, her investigation of Kelimmat Ha-goyim unfolds in a part of her book devoted to “Science and Jewish Identity.” Here, however, the fit with the larger rubric is less snug. In fact, the work’s center of gravity and main innovations lie, as she indicates, in its historical awareness and astonishingly extensive use of Latin sources. Unfortunately, some of the more arresting historicizing insights, and various subtle touches that inform it, go unregistered. For example, Duran chalks up the abandonment of the Law on the part of early Christians to something like a marketing decision aimed at making the new faith appealing to converts who would find observance of the commandments (and circumcision) too onerous. In casting Jesus and his disciples as unattractive simpletons, Duran calls them, as Kozodoy notes, “pious fools.” It is worth adding that he invokes a talmudic category (hasid shoteh), in this way adroitly situating Christianity’s founders in a (proto-)rabbinic milieu while suggesting the dim view that the ancient sages would have taken of them.

There is a drawback to the focus on rationalism as well, for sometimes Duran’s historical approach reaches beyond purely philosophical critique. For instance, with regard to the doctrine of transubstantiation—the idea that the body and blood of Jesus were present in the consecrated bread and wine of the Eucharist—Duran himself notes that while it defies rational principles, Christians could simply cast it as a mystery beyond reason’s grasp. However, he goes on to argue that this central tenet of medieval Catholicism had no basis in the texts of the New Testament.

Finally, though Kelimmat Ha-goyim is an undeniably inventive and impressive work, Kozodoy could have been more critical in assessing the quality of some of its arguments. For example, Duran fails to offer a historically convincing explanation of reasons for the later perversions of Christianity’s message as preserved in the New Testament by those whom he calls “the deceivers.” Later polemicists, like the 17th-century Venetian rabbi

Leone da Modena, would improve on Duran in this respect, in part due to their more extensive familiarity with early Church history in its larger Greco-Roman setting.

Through his writings as Efod, Kozodoy observes, Duran sought expiation for his defection from Judaism and the sins he was compelled to commit as Honoratus de Bonafide. In the concluding part of her book, entitled “The Efod Atones for Idolatry,” Kozodoy explores Duran’s “reconception of Judaism under the pressures of his life as a converso.” She does so by delving deeply into several interlocking topics, including faith and reason, intention and deed, spirituality and eternal felicity, astrology, medicine, and magic. Her overall aim is to unpack Duran’s teaching regarding what he called “the true wisdom of the Torah.” Two key foci were his Bible-centered vision of Jewish spirituality and his emphasis on the central role of intention in spiritual attainment. It is not hard to see how these mesh with the sort of converso religion Duran and his ilk were forced to practice, since conversos were debarred from open observance of the commandments or openly studying rabbinic texts.

Duran presented his bibliocentric spiritual vision in the last of his works to survive, Ma’aseh Efod, which he completed in 1403. This study in Hebrew grammar came with a substantial introduction that Isadore Twersky brought to scholarly attention some four decades ago. Though it has been discussed with some frequency since, Kozodoy makes some important contributions to our understanding of Duran’s biblical scheme, in part by placing it in a converso context and in part by viewing some of its key ideas from a fresh angle. For example, Duran insists that “an occult virtue” (segulah) inheres in holy writ, imbuing scripture with salvific powers that allow those who engage with it to attain felicity, even if they do so with little or no understanding. Kozodoy shows that this amounts to a religious appropriation of ideas about magnets and medicines developed by philosophers and physicians working in Duran’s larger milieu, while also suggesting that his biblicism could have provided “hope and succor” to simple Jews, not to mention conversos caught in “a desperate and drastically altered historical circumstance.”

As regards Duran’s insistence on the centrality of intention to Jewish religious life, it was, of course, in part a response to the classical Christian charge that, in contrast to Christianity, Judaism is legalistic, valorizing outward observance over inner spirit. Late medieval Sephardic thinkers were especially sensitive to this allegation, and even as Duran denied the claim in principle, he not only acknowledged the phenomenon of rote observance of the commandments but regarded it as the reason for the Jewish people’s “being crushed by the sword and flame in captivity and shame again and again in the time of this great exile.” Tentatively but plausibly, Kozodoy suggests that Duran’s preoccupation with this theme intensified after 1391 as he read heavily in Christian literature including the Pauline epistles, with their stress on faith over “works” as the means to salvation.

Duran, Kozodoy tells us, remained a Christian until the end of his life:

Although it has been often thought that Duran returned openly to Judaism in his later years, we have no evidence that he availed himself of this route; instead, what we have is continuous evidence of a public life as a Christian even as, in his writings . . . he reveals an inner life as a Jew.

As Kozodoy observes, scholars have long wondered how the man who now called himself Honoratus de Bonafide could have written works in Hebrew at all, let alone anti-Christian polemics, without being targeted by the (papal) Inquisition. It may be, Kozodoy suggests, that in Duran’s day, long before the establishment of the infamous Spanish Inquisition in 1478, inquisitors did not yet pose a real threat to Judaizers. Nor is it clear, she says, that Duran was known to be writing as a Jew, let alone as Efod. Even accepting such points, one can certainly admire Duran’s courage in circulating, however circumspectly, works that risked his ruin, if not his life.

For all its virtues, Kozodoy’s book is not the final word on Duran, as I believe its author would be the first to acknowledge. In a study that will soon be published in a Festschrift in honor of Yosef Kaplan, Joseph Hacker presents startling new evidence of Duran’s presence in Italy in 1398, around the time to which Kelimmat Ha-goyim has been dated, and 1413, a decade after completing Ma’aseh Efod. This casts a very different light on Kozodoy’s claim that Duran’s post-1391 theology did not require conversos to engage in flight or in an immediate formal “return to Judaism.” Apparently, Honoratus de Bonafide more than once found himself in a situation where he could, like other forced converts, begin life anew as a professing Jew—and chose to return to Spain.

On another plane, for all its many accomplishments, Kozodoy’s synthetic approach necessarily precludes the comprehensive treatment that many of Duran’s works await. Thus, Kozodoy describes Ma’aseh Efod as “by far the most important of Duran’s writings,” but gives sustained attention only to its introduction. She at times discusses it as if it comprised the whole of the work, leaving the nature and extent of Duran’s contributions in the field of Hebrew language study (and some of their motivation) to her own future research, or that of others.

Still, such omissions are decisively outweighed by her book’s many virtues. In addition to those mentioned already, it should be added that Kozodoy’s study often draws fascinating internal connections between Duran’s works. He was, as Kozodoy writes, a “consummate master of multilayered allusion,” and even his most intelligent and literate readers have often been left feeling that something crucial has been missed. Kozodoy’s careful, subtle, and probing book sheds a great deal of light on one of the most perplexing figures in the history of the Jews of Spain.

Suggested Reading

Meanwhile, on a Quiet Street in Cleveland

Two Jewish kids from Cleveland created Superman. Why does the Man of Steel still fascinate us?

Leapsniffing through the Vimveil: Avram Davidson’s Fantastic Fiction

Gods in fishbowls, men who are apes, and a Jewish dentist abducted by aliens: the fantastic fiction of Avram Davidson was almost as strange as his life.

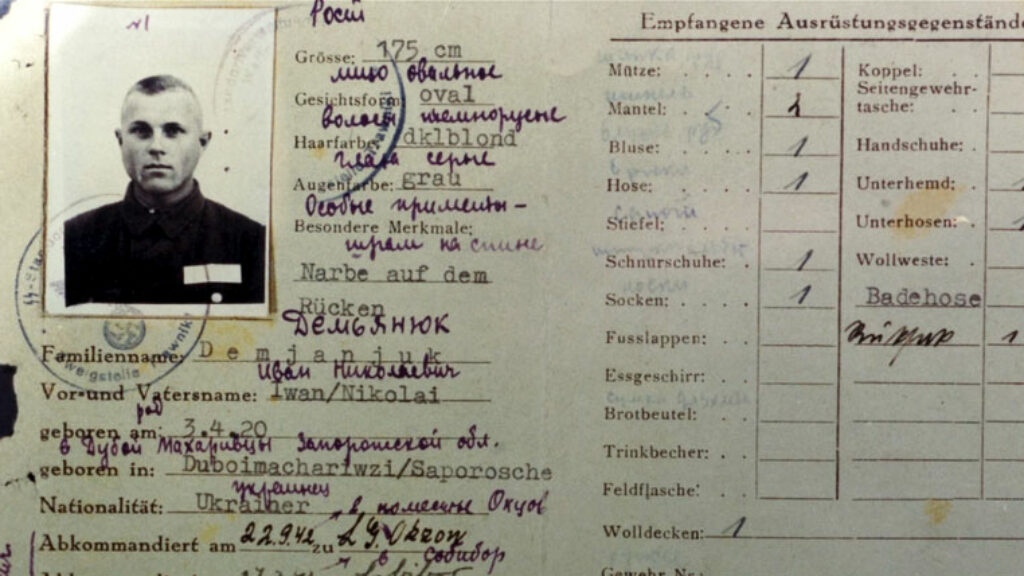

Ivan the Terrible?

A new miniseries from Netflix manages to maintain the tension of the long-decided, if not entirely resolved, case of John Demjanjuk.

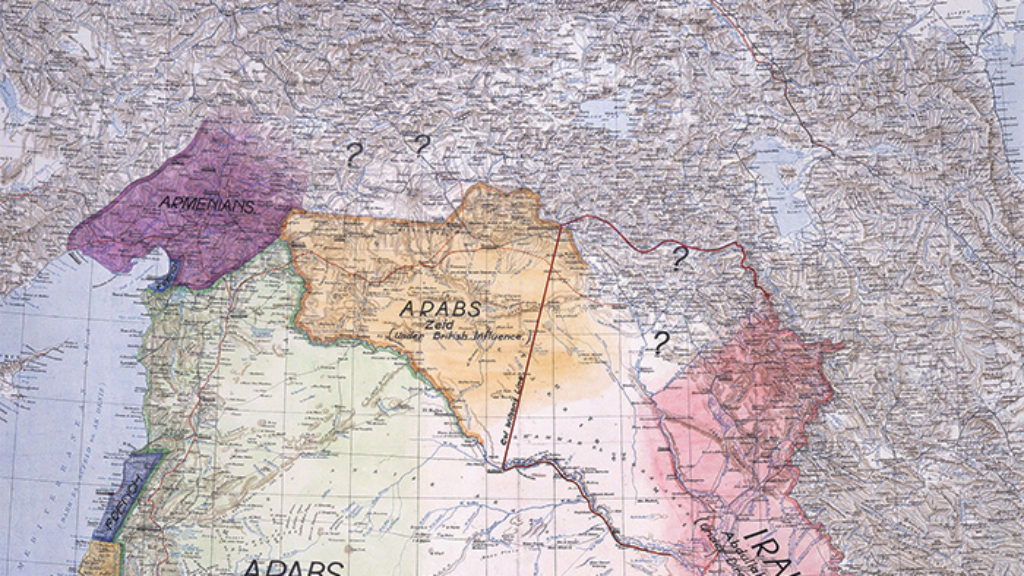

Chaim of Arabia: The First Arab-Zionist Alliance

Chaim Weizmann regarded his 1919 agreement with Emir Faisal as an epoch-making treaty. That didn’t turn out to be the case, but a century later an Arab-Zionist alliance may be reemerging.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In