If This Is a Man

The unexpected news of the passing of Primo Levi on April 11, 1987 shocked not only his family and friends but also readers of his work around the world. Levi’s death, the result of a fall down the narrow stairwell of his apartment building in Turin, was officially pronounced a suicide. In part because he left no message behind, some of his close friends doubted that he had killed himself. Others, including his biographers, have agreed with the verdict of suicide, an issue to which I shall return. One matter is beyond dispute: In the large and still growing corpus of literature written in response to the Nazi genocide of the Jews, Levi has become canonical. The reasons for this are amply displayed in The Complete Works of Primo Levi, a handsomely produced three-volume gathering of almost everything Levi wrote, edited by one of his most distinguished English translators, Ann Goldstein.

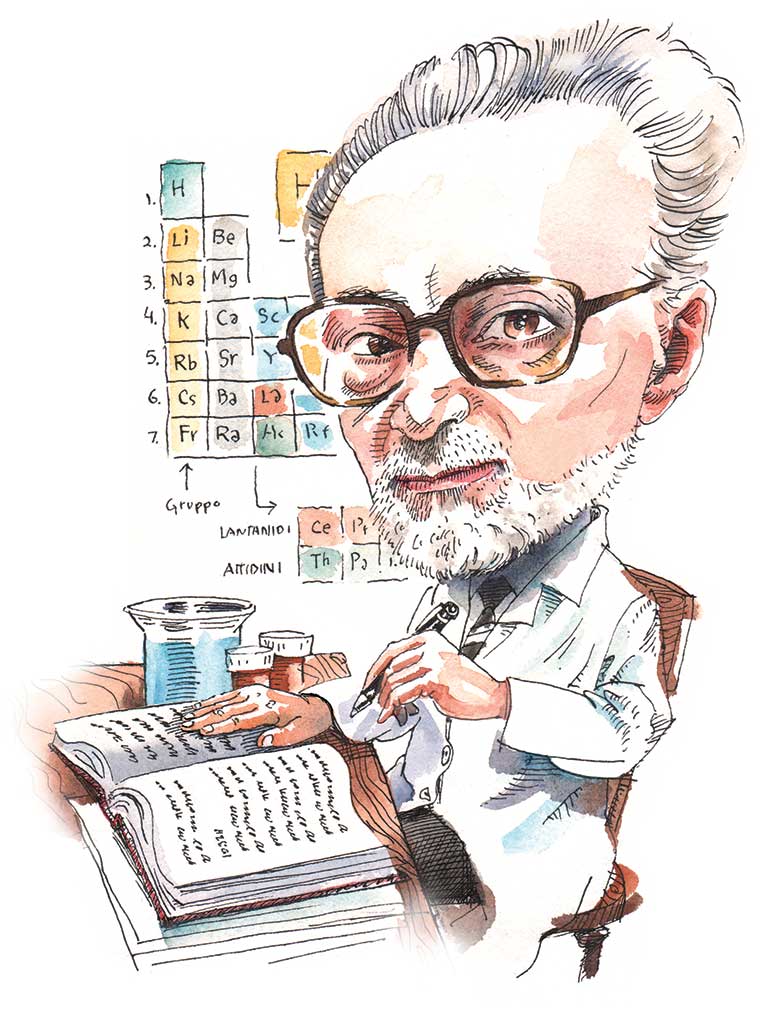

Totaling more than 3,000 pages, this large collection will generously reward all of the time that readers can devote to it. What they will discover will be both familiar and new: The three volumes present 14 of Levi’s books previously published in Italian, but some of the material is appearing for the first time in English. Thirteen of these books have new English translations, one of which, Stuart Woolf’s rendering of Levi’s Auschwitz memoir, Se questo è un uomo, appears in a partially revised translation and with a new title: If This Is a Man instead of Survival in Auschwitz. The breadth of Levi’s literary range in these pages—memoirs, essays, novels, short stories, poetry, science fiction, newspaper articles, book prefaces and forewords, book and film reviews—is striking. Equally striking is the variety of subjects covered: not only the Shoah but science, technology, language, work, games, the mysteries of the universe, literary and political questions, aspects of the Jewish tradition, and more. A Cartesian by nature and a scientist by training, Levi had an endlessly curious, probing mind. He often claimed that he was first and foremost a chemist and not a professional writer, but anyone who reads Levi with care will be moved by the sober lucidity, subtlety, concision, and analytical power of his prose. As Saul Bellow put it, “In Levi’s writing, nothing is superfluous and everything is essential.”

Levi’s first and deservedly much-praised book, If This Is a Man, is a memoir of the 11 months he spent as a Jewish prisoner in Auschwitz, “a name without significance for us at that time.” In Night, his own first book, Elie Wiesel struck a similar note: “‘Auschwitz.’ Nobody had ever heard that name.” If, today, the name registers with disturbingly gruesome significance, it is, in no small part, owing to books such as Levi’s and Wiesel’s, which opened the eyes of millions of readers to the atrocious reality of life and death in the most notorious of the Nazi camps. In contrast to Night, which raises profound theological questions, Levi’s memoir centers on the Nazis’ brutally systematic assaults on the human condition, or what is left of it when virtually everything human is stripped away:

Nothing belongs to us anymore; they have taken away our clothes, our shoes, even our hair; if we speak, they will not listen to us, and if they listened, they would not understand. They will take away even our name; and if we want to keep it, we will have to find in ourselves the strength to do so, to manage somehow so that behind the name something of us, of us as we were, remains.

If This Is a Man is an elaboration of this human reduction—of “life on the bottom”—and of what it took to endure such radical deprivation and still retain some semblance of humanity. Many inmates lost a saving link to their innermost being and were annihilated in spirit before they were physically destroyed. Levi was fortunate and survived. His calmly drawn but riveting memoir of what it took to do so is a moral and literary achievement of the highest order.

He wrote the book out of a strong personal need—as an act of “interior liberation”—but also with the aim of informing his family, friends, and the general public about the sufferings that he and millions of others underwent in the vast Nazi camp system. The book’s tone is reflective, not admonitory; all the same, he wanted his readers to see in the death camps “a sinister signal of [a] danger” that might recur. As he wrote in his last book, The Drowned and the Saved, “It happened once and it can happen again. This is the heart of what we have to say.”

He never left off saying it, but he said much else as well. In the last 40 years of his life, while raising a family and working for most of those years as a chemist and manager of a paint and varnish factory, Levi was an astonishingly productive writer.

The Complete Works does not include Levi’s Auschwitz Report, a slim volume that Levi wrote with Dr. Leonardo De Benedetti, at the request of Russian authorities, about conditions in the camp in 1945. Also omitted is The Search for Roots, a personal anthology of 30 literary sources, with commentary, that Levi put together at the request of his Italian publisher, Einaudi, to reveal the works that had an important influence on his writing. Among others, Levi cites The Book of Job, Paul Celan’s famous poem “Todesfuge,” Hermann Langbein’s Menschen in Auschwitz, and Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers, all of which are notable for highlighting themes of victimization and injustice. Otherwise, readers will find here virtually everything that Levi published in his lifetime: The Truce, a brilliantly rendered picaresque account of his adventures during the long and circuitous journey back home through the war-ravaged countries and decimated Jewish communities of Eastern and Central Europe; his two novels, The Wrench, a celebration of the dignity of work, and a story about Jewish partisan fighters during the war called If Not Now, When?; The Periodic Table, a work in a creative category all its own, which figuratively aligns elements of the periodic table with historical and autobiographical episodes; several collections of essays, commentaries, short stories, and poetry; and The Drowned and the Saved, a somber and acutely perceptive series of essays on the reality and meanings of Auschwitz written four decades after Levi’s liberation from the camp. For those who want to read more selectively and focus only on the “essential” Levi, a case can be made that Levi’s first and last books—If This Is a Man and The Drowned and the Saved—will remain indispensable for anyone who feels compelled to come to grips with “what man’s presumption made of man in Auschwitz.”

The name of this camp has become emblematic of the Nazi genocide as such, so its specific historical significance is worth recalling. Simply put, Auschwitz was the largest single site of mass killing in human history. Of the approximately 1.1 million people murdered there, some 90 percent were Jews. The enormity of that crime defied understanding to most of those who witnessed it, but in his first book Levi was able to evoke its madness, cruelty, and near-incomprehensibility with compelling clarity. He viewed the Nazi slaughter as “the central event, the scourge” of the 20th century, but he managed to write about it, astonishingly, in a tone of measured and civilized restraint. That tone changes radically in his last book, The Drowned and the Saved. Reading it, one sees that Levi’s narrative and analytic powers remain intact, as do the humane intelligence and refined moral imagination that are the signature of everything he wrote. But in place of his characteristically calm and temperate voice there are flashes of anger and accusation that are rarely seen in the earlier writings. Moreover, and disturbingly, many of these sharply negative accusations are directed at himself.

Levi’s commentary on the duty to remember, but also memory’s sometimes fallacious and unreliable character, is masterful. The same is true of what he has to say about a range of other subjects in The Drowned and the Saved: “useless violence”; the advantages and disadvantages of being an intellectual in the Nazi camps; the role of Germans as perpetrators and bystanders and the post-war legacy of German responsibility; the possibilities of atonement and forgiveness after Auschwitz; and, most tellingly, complicity and the morally ambiguous “gray zone” of life in the camps. Here he brought his thinking to a stunning, but also troubling, level of closure. In these chapters it becomes clear that, toward the end of his life, Levi was beset by acute feelings of guilt, shame, futility, and failure. His original plan was to write a sociological study of camp life, but what he ended up with was a self-portrait of a man struggling with the anguish of his own survival:

Do you feel shame because you are alive in the place of someone else? A person more generous, sensitive, wise, useful, and worthy of living than you? You cannot exclude the possibility [. . .] It’s just a supposition [. . .] that each is a Cain to his brother, that each of us [. . .] has betrayed his neighbor and is living in his place. It’s a supposition, but it gnaws at you; it’s nesting deep inside like a worm [. . .] it gnaws, and it shrieks.

As his meditation on the shame of survival deepens, Levi rapidly moves from supposition to accusation and even self-indictment: “Maybe I was alive in someone else’s place, at someone else’s expense. I might have supplanted him, killed him. Those who were ‘saved’ in the camps were not the best of us, the ones predestined to do good, the bearers of a message. [. . .] Those who survived were the worst. [. . .] The best all died.”

Levi was, of course, being much too hard on himself. In looking back at his time in Auschwitz, he discovered no transgressions that would justify such a harsh self-indictment. Nor has anyone else uncovered any evidence of such behavior. But, as Levi’s writings at the end of his life make painfully clear, not everyone who managed to outlast the deprivations and terrors of the Nazi camps emerged free of disabling feelings of guilt and shame, what he called “the survivors’ disease.”

He describes such suffering in recalling Lorenzo, an Italian civilian worker in Auschwitz who helped to keep him alive by regularly giving him part of his daily food rations and other small acts of kindness. Levi wrote about Lorenzo briefly in If This Is a Man and later more fully in the moving biographical sketch, “The Return of Lorenzo.” When Levi reconnected with Lorenzo after the war, he found “a weary man [. . .] a weariness from which there was no recovering. [. . .] [H]is margin of love for life had narrowed, had almost disappeared. [. . .] He had seen the world, he didn’t like it, he felt it was going to ruin; living no longer interested him. [. . .] He was confident and consistent in his rejection of life.” As Levi presents Lorenzo, he had had enough of life, withdrew into solitude, and chose the terms of his own death.

Did Levi succumb to a similar affliction? The entry for April 11, 1987 in the chronology of his life in The Complete Works concurs with the official judgment, listing his death as a suicide. In his last year, Levi was contending with severe depression, some other complex medical issues, unrelieved domestic worries, a diminution of his energy and creativity, and an accumulation of other concerns that were wearing him down. He was fond of the Yiddish expression Ibergekumene tsores iz gut tsu dertseyln (troubles overcome are good to tell), but Levi was unable to overcome all of his tsores. The details of this time are poignantly set forth in the final chapters of Ian Thomson’s fine biography, and they make a strong case that by the time he died Levi had reached the limits of his endurance. He said as much in a distressed phone call to Elio Toaff, the chief rabbi of Rome, on the morning of his death. I myself received the following letter from him just two days earlier:

Dear Alvin,

Thank you for your letter of March 13, and for the fine essay enclosed. Yes, in fact we have been out of touch for a while: it is my fault, or at least mine was the missing link. My family has been struck twice, and things at home are going pretty badly: my mother, 92, is in a bed paralyzed for ever, I came home yesterday from a hospital where I underwent a serious surgical operation; but mainly, as a consequence of all the above, I am suffering from a severe depression, and I am struggling at no avail to escape it. Please forgive me for being so short; the mere fact of writing a letter is a trial for me, but the will to recover is strong. Let us see what the next months will bring to all of us, but my present situation is the worst I ever experienced, Auschwitz included.

Best wishes for your summer trip in Europe, and warmest regards to all your dear family and to you.

Primo

Before I could reply, Levi was gone.

When he heard the news, Elie Wiesel said “Primo Levi died at Auschwitz forty years later.” What role should knowledge of Levi’s end play in understanding and assessing his writing? Ian Thomson argues that “Levi and his books are not one and the same. If anything, his suicide reminds us that the life of the artist does not run parallel to his art.” Sam Magavern, author of a book-length critical study of Levi, agrees with Thomson, arguing that Levi’s severe depression was probably biochemical in origin and should play no role in the interpretation of his work. Carole Angier, another Levi biographer, similarly argues that “Primo Levi’s death was personal. It was a tragedy, but it was not a victory for Auschwitz.”

On the other hand, in her powerful reading of The Drowned and the Saved, Cynthia Ozick limned the presence of camp-inflicted rage in Levi’s work and described his book “as the bitterest of suicide notes.” Ferdinando Camon, who knew Levi and interviewed him at length, agreed, writing that his death had to be “backdated to 1945. It did not happen then because Primo wanted (and had to) write. Now, having completed his work [. . .] he could kill himself. And he did.” But if he did, how might such a death shape a reader’s understanding of Levi’s profound humanism? At the time Leon Wieseltier wrote despairingly that Levi “spoke for the bet that there is no blow from which the soul may not recover. When he smashed his body, he smashed his bet.”

In an essay in the Boston Review, Diego Gambetta carefully sifted through these diverse opinions, concluding that what put Primo Levi most at risk was the writing itself:

[W]riting about the experience of the camp, rather than being a cathartic process, makes life much harder to live. The detailed revisiting of appalling atrocities and infinite human misery wears the writer out and [. . .] makes him increasingly suicidal. [. . .] [I]f Levi’s death were a suicide, his gesture would leave the value of his work intact. He would have succumbed not to Nazism, but to an altogether different thing: the high personal cost of bearing witness to the Holocaust by writing about it.

These arguments have gone on for almost 30 years now and are likely to continue. Inasmuch as they go to the heart of who Primo Levi was and how one is to read and derive meaning from his writings, they are likely to remain serious concerns for future readers.

Likewise debated and also unresolved is the question of whether or not Levi is to be regarded as primarily a “Jewish writer.” In Italy, this has not been an issue, but his reception in America has been different. For example, in a lengthy and overwhelmingly negative review essay that appeared in Commentary soon after the American publication of If Not Now, When? Fernanda Eberstadt faulted Levi for having “a tin ear” for Judaism and only scant knowledge of the Jews he depicted. She derided the book as hackneyed, leaden, sentimental, and propagandistic—in sum, a failure. Levi was, she argued, simply incapable of representing Jewish experience at large in an informed way. Levi was hurt by the review and replied to it in a long letter to Commentary, reprinted in The Complete Works. In it he wrote, “I am implicitly accused of being assimilated. I am.” Ann Goldstein, who spent years editing these volumes and translated three of his books, said recently that Levi “wasn’t especially Jewish. He was probably Jewish in the way that people are here,” meaning Manhattan. She acknowledges that his wartime experiences awakened him more fully to his Jewish identity and that, in some of his writings, he touched on Jewish subjects, but she does not see him as a Jewish writer, an assessment that is not quite right either.

Primo Levi was born into a Jewish family in Turin that was well integrated into Italian society and culture but also kept its affiliation with the city’s Jewish community. A few Jewish holidays and rituals were maintained, but the Levis, like many Italian Jews of their generation, were not observant Jews. He had some early Hebrew schooling and became a bar mitzvah when he was 13, but he was never religious and, until the onset of the war years, his Jewish identity was marginal to the life he led. With the introduction of fascist Italy’s race laws of 1938, everything changed: “The race laws have stamped me like you stamp sheet metal; now I’m a Jew. They’ve sewn the star of David on me and not only on my clothes.” In December 1943, he was captured as a partisan and confessed to being a Jew. Deported to Auschwitz in February 1944, the incriminating brand of his birth became even more emphatic:

At Auschwitz I became a Jew. The consciousness of feeling different was forced upon me. Someone, for no reason in the world, decided that I was different and inferior: my natural reaction was, in those years, to feel different and superior. [. . .] In that sense, Auschwitz gave me something that has stayed with me. By making me feel Jewish, it inspired me to retrieve, afterward, a cultural patrimony that I hadn’t had before.

During his time in the camp, Levi was thrown together with large numbers of Eastern European Jews. The Ashkenazi culture they represented was barely known to him, and much about it both baffled and intrigued him. As chronicled in The Truce, his many months of wandering through Eastern Europe opened his eyes to “an exploded, mortally wounded Jewish world.” Once back in Italy, he spent years investigating and paying tribute to the richness and nobility of that world. He taught himself Yiddish, picked up more Hebrew, and deepened his knowledge of Jewish folklore and folkways, Jewish humor, theater and music, and Jewish texts. References to the Bible and Talmud, the Passover haggadah and Shulchan Arukh, Sholem Aleichem and Isaac Bashevis Singer appear in The Complete Works; the title of If Not Now, When? is, of course, taken from Hillel’s famous saying in Pirkei Avot. He also wrote about Itzhak Katzenelson, Franz Kafka, Paul Celan, Léon Poliakov, and other Jewish writers. In sum, in the post-war decades Levi read and wrote his way into a Jewish cultural patrimony that was broader and richer than anything he had known in his early years. It shaped his sensibility as a man and author and also directed the response of many of his readers in ways that gratified him:

If This Is a Man has been read as a book written by a Jewish author…and as a result of having been defined as a Jewish writer, I actually became one. I accept, willingly, [the] description [of me] as a Jewish writer.

Like that of most truly great writers, Levi’s work was multifaceted, but he will inevitably be remembered as the writer who survived the Nazi genocide and dedicated much of the rest of his life to seeing that it be remembered. As he understood it and wanted others to understand it, that crime was like none other. He called it “a unicum” and did whatever he could to preserve and transmit its memory: “If we are silent, who will speak? . . . And so we must speak.” In remaining faithful to that injunction, Levi found his most lasting voice as a writer and fulfilled a fundamental Jewish imperative: zakhor.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Faith in Doubt

Can doubt provide the space that allows secular and religious Jews to coexist in Israel?

Letters, Fall 2019

Austro-Hungarian Eden?; The Diaspora Strikes Back!; In Performance There Is Problem; Tact, Truth, and Tercets; Mameloshn

The Kid from the Haggadah

A 1944 poem, translated by Dan Ben-Amos.

The Milchik Way

Katchor seems to take his cue from these menus with their meandering columns of dense text; their indirection parallels and feeds his own.

gwhepner

WHAT HAPPENED TO PRIMO LEVI WHEN HE COULD NO LONGER TALK OF TROUBLES HE HAD OVERCOME

There is a famous book that's by the ancient Roman doctor, Galen,

called Peri Alupias, “About Not Being Distressed.”

For overcoming distress, the solution that appeared to be the best

for Primo Levi, iberkumene tsores iz gut tsu dertseyln,

which in Yiddish means: it's good to talk of troubles one has has overcome,

only worked for him as long as he was able to write

as brilliantly as he did, for once he couldn't, he gave up the fight

for life he'd won in Auschwitz, giving up in order to be dumb.

Unable to tell all the world about his troubles he

perhaps found rest in silence, just like Hamlet, tragically.

[email protected]

gwhepner

WHAT HAPPENED TO PRIMO LEVI WHEN HE COULD NO LONGER TALK OF TROUBLES

HAD OVERCOME

There is a famous book that's by the great Hellenic doctor, Galen,

called Peri Alupias, “About Not Being Distressed.”

For overcoming distress, the solution that appeared to be the best

for Primo Levi, iberkumene tsores iz gut tsu dertseyln,

which in Yiddish means: it's good to talk of troubles one has has overcome,

only worked for him as long as he was able to write

as brilliantly as he did, for once he couldn't, he gave up the fight

for life he'd won in Auschwitz, giving up in order to be dumb.

Unable to tell all the worlkd about his troubles he

perhaps found rest in silence, just like Hamlet, tragically.

[email protected]