Religion and Politics: A Response to Shlomo Riskin

Intellectual history is rich in ironies, and Judaism is no exception. The first person to set out in systematic fashion the principles of Jewish faith was Moses Maimonides. He was then accused of lacking Jewish faith. His books were burned, first by Jews, then by non-Jews. Wherever in his writings he sets out these principles, he includes belief in the resurrection of the dead. Yet he was accused of denying belief in the resurrection of the dead. So intense was the pressure that he felt obliged to write an entire treatise in defense of his position.

He makes a wry comment in the opening paragraph of the treatise. He says that however hard you strive to make your position clear, it will be misunderstood, and that applies to God himself. There can hardly be a clearer statement of monotheism than the first line of the Shema, “Hear, O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is one.” Yet, Maimonides notes, Christians take this very verse as evidence of the trinity. After all, it mentions God three times: the Lord, our God, the Lord. Therefore God is three-in-one. He adds, “If this is what happened to God’s proclamation, it is much more likely and to be expected to happen to statements made by humans.”

I am no Maimonides, but I am also no stranger to the experience of having my writings misunderstood. So I am grateful to Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, not only for his warm review of my book Not in God’s Name: Confronting Religious Violence (“Religion and Power,” Summer 2016), but also for the opportunity to correct his misunderstanding of it.

He attributes to me views he knows that I, like him a Religious Zionist, do not hold. He suggests that I believe Jews and Judaism embrace powerlessness. Not only do I not believe this, I cannot understand how, after the Holocaust, any Jew could believe it. A thousand years of the Jewish experience of powerlessness in Europe added to the vocabulary of humanity words like disputation, expulsion, forced conversion, inquisition, auto-da-fé, ghetto, and pogrom. That is not a fate one would wish on anyone.

One of the turning points of modern history was the Evian Conference convened by President Roosevelt in July 1938. Representatives of 32 nations gathered in the French spa town, knowing that a terrible fate was about to befall the Jews of Europe. Not one opened its doors. At that moment Jews knew that they had not one square inch of the earth’s surface they could call home in the Robert Frost sense as the place where, when you have to go there, they have to let you in. Lacking power, Jews lacked defensible space. That must never happen again.

But Israel, the land and state, is more than a refuge and a home. From the first recorded syllables of Jewish time—God’s words to Abraham in Genesis 12—Jewish history has taken the form of a journey to, or life within, the land God called holy. It is the leading theme of the Mosaic books. Genesis is about the promise of the land: seven times to Abraham, once to Isaac, three times to Jacob. The other books from Exodus to Deuteronomy are about the journey to the land.

The Torah is not a set of instructions for the salvation of the soul. It is about the creation of a society that would constitute a protest against empires and imperialism, a living alternative to hierarchy and hubris, dramatized in the Torah in the form of the Tower of Babel and Egypt of the pharaohs. It would aim at—to use the late Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein’s resonant phrase—societal beatitude. That requires a land and self-governance; in short, it presupposes power. In the course of their almost four thousand years of history, during which Jews have lived in every country under the sun, only in Israel have they ever enjoyed this ability to create their own society in the light of their highest ideals.

Judaism never advocated powerlessness, but it did protest attributing religious significance to power. Power, in Tanakh, is the prerogative of God alone, which He delegates to human beings but under strict conditions. Judaism was unique in the ancient world in separating political from religious authority. The king was not a priest. The priest was not a king. Prophets were mandated to criticize both. The king had no ecclesiastical role. Monarchy was divested of its sacred aura. Nor did the king have any special privilege in interpreting legal texts. In a recent study, Michael Walzer, the Princeton political philosopher, called biblical Israel an “almost democracy.”

This separation of powers was breached by the later Hasmonean kings, who combined monarchy with the high priesthood. The Talmud records the rabbis’ protest: “Let the crown of kingship be enough for you. Leave the crown of priesthood to the descendants of Aaron.” The devastating mixture of religion and power created incurable rifts within the Jewish people, leading to two of Judaism’s greatest disasters, the Great Rebellion against Rome and the Bar Kokhba revolt.

The politics of Judaism is unique in that Israel as a body politic had not one foundational moment but two. There was the social contract, described in 1 Samuel 8, which turned a loose confederation of tribes into a single nation under the sovereignty of a king. Before that, though, there had been the social covenant, entered into at Mount Sinai, that constituted the people as an eida under the sovereignty of God.

In contemporary terms, the contract created a state; the covenant created a society. The contract was about power; the covenant was about collective moral responsibility. This duality had fateful consequences. It meant that even when Jews lost the contract, they still had the covenant. Even when they lost their land, they still kept their identity and responsibility, expressed by the sages in the principle kol Yisrael arevin zeh bazeh, “All Jews are sureties for one another.” No one need idealize this fact. It was still exile; it was still powerlessness; but it showed that Judaism could survive the loss of power.

This turned out to have consequences that went far beyond Judaism. Rabbi Riskin quotes in his review Eric Nelson’s fine study The Hebrew Republic. I urge him to re-read it, since the point it makes is precisely the one I make in Not in God’s Name, namely that it was the Hebrew Bible that inspired figures such as John Milton and John Locke to formulate the ideas—among them republicanism and the doctrine of toleration—that led to the free societies of the modern world. Nelson points out, for example, that it was the sharp critique of monarchy to be found in Midrash Devarim Rabbah and the Torah commentary of Rabbeinu Bachya that were key influences on Milton. Through their studies of the Hebrew Bible and the rabbinic literature, the Christian Hebraists learned to separate civil power from religious authority.

The person who saw this most clearly and described it most lucidly was Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America. Coming from Catholic France where religion had power and was widely resented, he was astonished to find that in America, where it had no power, it had enormous influence. To understand this, he questioned many clergymen. He discovered that religious leaders “seemed to retire of their own accord from the exercise of power, and that they made it the pride of their profession to abstain from politics.” They knew that politics is divisive, and therefore if religion became involved in politics, it too would be divisive. Tocqueville’s conclusion was that the more democratic a society is, the more dangerous it becomes “to connect religion with political institutions.” Rabbi Riskin knows this and has personally suffered from the politicization of Judaism in the current state of Israel.

I have made these points at length in several books, among them The Politics of Hope, The Home We Build Together, and my book on the challenges facing Jews and Judaism in the 21st century, Future Tense, and they have been made by other minds far greater than mine. To repeat: I am a Religious Zionist. I have never argued for a disempowered, de-territorialized Judaism, and I never will. But neither will I defend the toxic mix of religion and politics that has been the downfall of every culture that embraced it: Judaism in the late Second Temple period, Christianity in the 16th and 17th centuries, and radical political Islam today.

It was the Judaic understanding of the difference between religion and power—transmitted to the West by the Christian Hebraists, Puritans, and political philosophers of the 16th and 17th centuries—that led to the “new birth of freedom” in England and America after a century of religious wars. No other culture to my knowledge has ever produced this kind of liberty, resting as it does on Divine sovereignty, social covenant, social contract, the moral limits of power, and the separation of civic and religious authority. Now that parts of the world are again engulfed in religiously motivated war and terror, shall we not share with others those transformative insights? And shall we not remind ourselves of the danger of mixing religion and politics even in Israel?

Politics divides. Religionized politics and politicized religion divide absolutely.

Rabbi Riskin’s original article can be found here.

His rejoinder to Rabbi Sacks can be found here.

Suggested Reading

Unfinished Rock

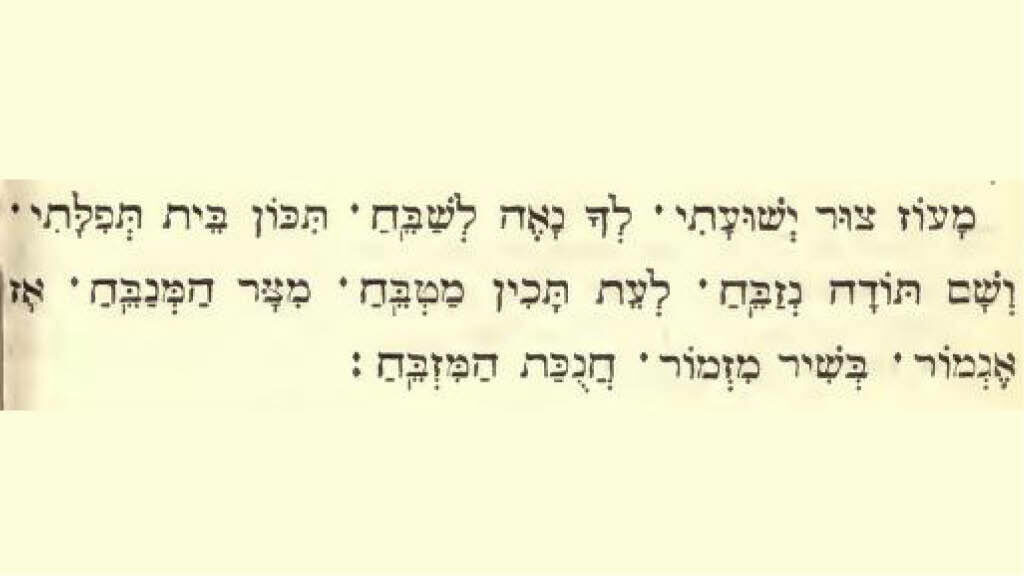

Why is the last stanza of Ma'oz Tzur unlike all other stanzas?

Where Abraham Walked

Preserved for centuries by Syrian Christians, spoken-Aramaic is now breathing its last.

Fanny and Hilde

If Court Jews provided economic services, the salon women provided cultural ones that were rarely available to rulers and other nobles in the stuffy environs of aristocratic society.

MAD Maus

A look inside the making of Art Spiegelman's classic graphic novel about the Holocaust.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In