Where Abraham Walked

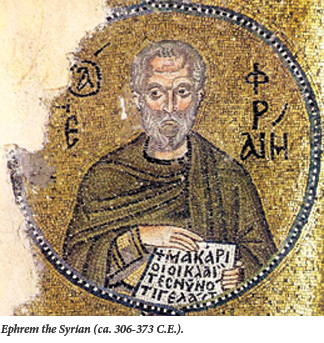

In the 4th century, Ephrem the Syrian, a Christian poet, teacher, and Church Father, dedicated these lines to a local holy man named Abraham who stirred memories of the biblical patriarch:

May ten thousand tongues give praise for our country,

Where Abraham and his sons walked,

Sarah, Rebecca, Leah, and Rachel too,

Even the heads of the tribes of Israel.

The verses evoke a Christianity profoundly aware of its Jewish matrix. Local sites of ritual remembrance made the narratives of scripture part of everyday life for Ephrem and his fellow Syrian Christians. Not far from his hometown of Nisibis (Nusaybin in modern-day Turkey), the city of Harran claimed the biblical Abraham as a resident. Christian pilgrims to the city prayed at a church they believed was built on the foundations of Abraham’s house; before returning home, they would fill souvenir vials from the well where Sarah watered the flocks.

For Ephrem, the name of Abraham expressed a bond between the land and two Mesopotamian communities that were brothers, neighbors, and rivals. Despite (or because of) this sometimes bitter rivalry, both often named their sons in honor of their father, Abraham. And both shared not only the Bible but also a language, Aramaic, a language that is only now breathing its last.

Aramaic is an umbrella term that includes an array of local forms of the language. Some of these forms may only have been spoken and have left no written evidence. Others, such as the dialects of Nabataea, Palmyra, and Hatra, are known almost exclusively from inscriptions. Still others, like the Aramaic preserved in the Dead Sea Scrolls or that of the Talmud have rich literary traditions. Syriac, the language Ephrem spoke, is most closely related to the Babylonian Aramaic of the Talmud (the Bavli). In fact, in recent research, Yifat Monnickendam argues convincingly for evidence of “mutual discourse” between Ephrem and the rabbis in matters relating to marriage, adultery, and divorce.

Jesus was, of course, an Aramaic-speaking Jew, as were many early converts to Christianity, and Syriac is not far from the Aramaic dialect he spoke. The Christians of Syria, Iraq, Iran, and Lebanon are ethnic Semites who belong to the Syriac family of churches, not to the Greek (or Byzantine) tradition. Syriac tradition is the only fully articulated expression of Christianity that preserves the Aramaic language and worldview of Jesus and his disciples, untouched by the influence of classical philosophy that dominated Christian thought in the West. Will it last?

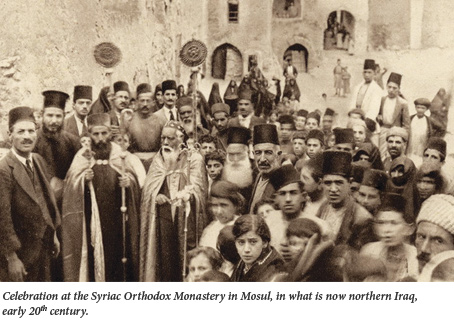

The 20th century saw the slow decline of the Jewish and Christian Aramaic-speaking communities of Syria; this century is witnessing their death, now drastically hastened by the violence that has engulfed Syria since March 2011. Syria’s ruling Assad family, members of the Alawite sect, a minority offshoot of Shiite Islam who constitute twelve percent of the population of Syria, have held power for more than forty years. They have done this in part by creating a coalition of fear, binding its Kurdish, Druze, Ismai’li, and Christian minorities together by promising to protect them from a takeover by Sunni fundamentalists. (In 1992, Hafez al-Assad permitted Syrian Jews to emigrate to the United States, France, or Turkey—provided they bought a face—saving round-trip ticket. Only two hundred or so Jews remain in Syria today).

Not content with violence perpetrated against its citizens, the Assad family, in collusion with Russian profiteers, systematically transformed a once breathtakingly beautiful country into cities dominated by gray, Soviet-style, concrete apartment blocks, further erasing its historical culture. The end of this regime, now all but inevitable, will be mourned by few. However, if events following the collapse of other Arab dictatorships are any indication, the fall of Bashar al-Assad will usher in a period of civil war and prolonged sectarian violence.

While the toll this will exact on the Syrian population as a whole will be unspeakable, it is likely to put an end to what is left of the beleaguered Christian minority. Christians throughout the Arab world know all too well of this fate. Anti-Christian violence following the fall of Saddam Hussein sent more than a million Christians into flight; many of those unable to escape died in raids on their neighborhoods and churches. Within days of Hosni Mubarak’s fall from power, violence against the Coptic Christian minority surged; there is evidence that Egyptian police stood by as churches and Christian businesses were plundered. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that we are witnessing the disappearance of Christianity from the very lands of its origin. And with the disappearance of Christian communities from the Middle East, the remnants of a culture and language even older than Christianity are also close to extinction.

The New Testament records the spread of Christianity to the Greek-speaking regions of Syria and Asia Minor, but there is no parallel account of the missionary impulse that took the faith eastward into Aramaic-speaking Mesopotamia, which Syriac speakers call Aram Beth Nahrin. The new faith followed ancient trade routes that linked Jerusalem to the Aramaic-speaking Jewish communities of Babylonia. Ethnic, cultural, and linguistic bonds between Judaism and Christianity continued in Aramaic-speaking western Asia long after the two faiths parted ways in the Greco-Latin West.

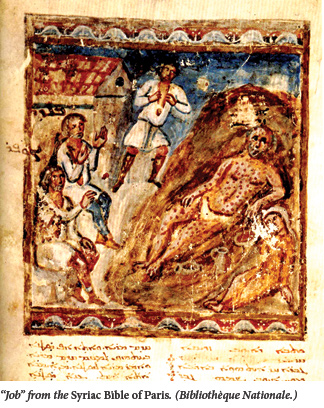

Evidence of ongoing Jewish-Christian interactions survives in a remarkable literary artifact known as the Peshitta Old Testament. The Peshitta Old Testament is a direct translation of the Hebrew Bible into Syriac. It is the product of many translators working over a period of several centuries. However, the five Books of Moses, known as the Pentateuch, were almost certainly translated by Jews in order to make it accessible to fellow Jews who no longer understood Hebrew. Because of the similarities between Hebrew and Aramaic, these translators made a point not simply to choose words that echoed the original Hebrew, but to preserve the rhythm and cadence of the Hebrew text wherever possible.

Remarkably, the Syriac-speaking Christians who continued the work of translation demonstrated deep familiarity with the intricacies of the Hebrew text, a phenomenon that has no known parallel in any other form of early Christianity. The only explanation is that these later translators were either converts from Judaism or members of Christian communities that preserved close cultural and linguistic ties to their Jewish origins.

Beginning in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, the various forms of Aramaic in use across western Asia began to be replaced by Greek, and eventually disappeared from use. Syriac represents not only an exception to this phenomenon, but a total reversal of it. By the early 4th century, Syriac had spread westward beyond the Euphrates and into western Syria; by the 5th, it was the common language of Christian culture throughout the region. Syriac provided a common literary medium for the spread of Christianity, while Christianity guaranteed the survival of Syriac. As a Syriac proverb has it: The pot found its lid.

With the coming of the Muslim Arabs in the 7th century, Syriac Christians faced a new challenge. Christians and Jews living under Islamic rule were regarded as “People of the Book.” Their possession of a revealed scripture meant that they were accorded, at least in theory, a degree of tolerance (though this should not be overstated). The immediate consequence for Syriac Christians was that they were no longer subject to political and military reprisals from rival Christians of Byzantium.

However, Syriac Christian culture was threatened by the growing dominance of the Arabic language. Syriac was not only spoken by a large majority of Christians who found themselves living under Muslim rule, it was also the language of a literary culture that had flourished since the time of Ephrem. Within a hundred years of the Muslim conquests, Syriac was displaced as the language of everyday life in Dar al-Islam, “the House of Islam.”

In contrast to their Greek-speaking counterparts in the monasteries of Jerusalem who embraced Arabic, Syriac Christians resisted this trend and continued to use Syriac as the language of worship and ecclesiastical affairs. Once Arabic had penetrated everyday life to the point where Syriac was no longer intelligible to their congregations, the churchmen conceded the use of Arabic for worship, but only if the texts were first transliterated into the characters of the Syriac alphabet. The strategy was more symbolic than real: although the priest was reciting the public parts of the liturgy in Arabic, the texts from which he was reading were written in Syriac characters.

The inventors of this coded language called it “Gershoni,” a term derived from Gershom, the first-born son of Moses. According to the interpretation of Exodus 2:22, the name refers to the fact that Moses was a “sojourner” (ger) “there” (sham). The interpretation was well suited to the growing sense among Syriac Christians that they had become strangers in their own land. Just how deeply this was felt may be judged by the fact that Gershoni remained in use until the 1970s.

Aramaic survived into the 20th century in the neo-Aramaic dialects spoken by Christians and Jews who lived in a vast region that encompassed what is now southeastern Turkey, northern Iraq, and northwestern Iran. The Jewish Aramaic dialects of Bohtan, Sanandaj, Urmi, Challa, together known as lishan didan (“our language”), were in common use until the 1950s. The Jews of Iraqi Kurdistan who found safe haven in Israel in the 1950s spoke a form of Aramaic with especially close affinities to Syriac. Syriac remains, for now, the everyday language in three villages northeast of Damascus: Ma’lula, Bax’a, and Jubb’adin. Ma’lula is predominately Christian, but the inhabitants of Bax’a and Jubb’adin are Muslims.

Ephrem is called a Father of the Church for his contributions to Christian doctrine during the formative period of its development, but he never really fit in that mostly Greco-Roman company. The Church Fathers used the abstract language of philosophy. Ephrem was a Semite who wrote exclusively in Syriac and abhorred philosophical rationalism. For Ephrem, this approach “sowed fields of death.” Poetry was the antidote to rigid doctrinal language; only it was sufficiently allusive to speak of divine realities.

Writing early in the 5th century, Jacob, bishop of the Syrian city of Sarug, celebrated Ephrem’s identification with the land and its culture: “[Ephrem] made a sweet spring of blessed water flow throughout our country . . . He is the crown of the Syrian nation . . . and among all Syrians, the master orator. “

Ephrem’s called his poems madrashe, the Syriac equivalent of the Hebrew midrash, a term that suggests teachings drawn from scripture. He set his madrashe to popular Syrian folk melodies and introduced them into the Sunday liturgy of his community. The strategy was more successful than perhaps even Ephrem imagined: his madrashe have remained a staple of Syriac worship, albeit in truncated form, to our own day.

Whatever the course of events in Syria, the Christian culture that had its origins there will not entirely disappear, but it will be profoundly diminished. A remnant may survive as strangers in their own land. Those who are able to emigrate will join diaspora communities across the globe. They will continue, at least for a time, to sing snatches of Ephrem’s madrashe, though with little comprehension. What had been a living tradition will become a set of historical artifacts, preserved largely in exile.

Suggested Reading

Ungoverning the Western Wall

After more ugly clashes at the Western Wall, two Israeli political scientists make a radical proposal.

Inside or Outside?

After the discoveries of the Cairo Geniza and the Dead Sea Scrolls, scholars of Judaism slowly began to reconstruct the 400-year period separating the latest parts of the Hebrew Bible from the earliest rabbinic compilations.

A Party in Boisk

The bodily joy a group of Boiskers took in fulfilling the commandment to study Torah is still surprising, and that may have something to do with the Torah they chose to study.

Friendship?

Margot takes in the whats and wherefores of Judaism but is never quite able to grasp the why: why someone would wish to be Modern Orthodox and live a life according to the strictures of traditional Jewish law.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In