The Future Past Perfect

In 1941 Stefan Zweig, the prolific genre-jumping Austrian writer, wrote to Manfred and Hannah Altmann, his wife Lotte’s brother and sister-in-law, about his impressions of Bahia, Brazil:

You cannot imagine what it means to see this country which is not yet spoiled by tourists and so enormously interesting—today I was in the huts of the poor people which live here practically from nothing (the bananas and mandiocas are growing round) and the children go like in paradise—the whole house with ground did cost them six dollars and so they are proprietors for ever. It is a good lesson to see how simply one can live and comparatively happy-a lesson to us all, who will loose every thing and are not enough happy now by the thought how to live then.

Zweig’s mistakes in grammar and spelling reflect the fact that the letter, like all those compiled in Stefan and Lotte Zweig’s South American Letters, were written in English to avoid being seized by censors in Great Britain where the Altmanns lived.

Zweig was in South America on a spectacularly crammed lecture tour that extended from August 1940 to January 1941. In addition to composing a slew of talks—and translating them, with Lotte’s help, up and down their polyglot scales between French, English, Yiddish, and Spanish—Stefan worked on various articles and drafted a hybrid travelogue-history book to be called Brasilien—Land der Zukunft (Brazil—Land of the Future). After a long period of declining spirits due, above all, to the war, but also to Lotte’s chronic asthma, and Stefan’s notorious “black liver” (his term for depression), the tour injected the Zweigs with a shot of Copacabana’s sparkling élan.

Among the many merits of this compelling, carefully edited volume is the insight it provides into a problem confronting all refugees from Nazi-dominated Europe: How might one begin conceiving a new vision of home while “the old country” went up in flames? They also tell the melancholy story of how, barely a year after the euphoric Bahia letter, Stefan and Lotte committed suicide in Petropolis, above Rio.

Zweig never relinquished his dream of Brazil as paradise. However, he came to feel that the Europe he carried inside himself was too vast to squeeze through those lushly overgrown gates. The narrative of these letters plays out like a protracted riff on Franz Kafka’s response to Max Brod’s question about whether hope might exist somewhere outside our own botched world: “Plenty of hope,” Kafka smiled. “Only not for us.”

The bulk of this compact volume consists of letters by Stefan and Lotte to Hannah and Manfred, presented in two batches: the first written during the busy tour alluded to above, the second beginning in August 1941, when the Zweigs returned to Brazil, and ending with the couple’s death in February 1942. The letters reveal Stefan in a rarely documented, familial mode. He worries about the Altmanns’ well-being, imploring them to make free use of everything the Zweigs have left behind from the house itself to “all clothes, underwear, linnen, overcoats and also whatever we have there.” And he devotes himself to reassuring the Altmanns that Lotte is flourishing in Brazil.

A persistent, lazy tradition of Stefan Zweig’s biographers dismisses Lotte as a passive shadow of the Great Writer. This collection allows Lotte’s own voice to tell a different story. The letters reveal Lotte, who was 27 years Zweig’s junior, as a forceful, cultivated person in her own right. In the midst of organizing their laborious travel, assisting with his frenetic production of lectures, and balancing a plethora of practical arrangements for her scattered family members, we see her closely observing the customs and characters encountered over the course of their wanderings. In an aside to her brother and sister-in-law about the American family caring for their daughter she writes, “They are very American, kind, gay and without any imagination beyond their own scope . . . somehow the life of the average American is always a rush . . .” The edge to her tone seems to fit the tall, elegant figure with strongly etched features and a flair for fashion that emerges in photographs.

Hardly an observation on Brazil’s beauty passes Lotte or Stefan’s pen without triggering guilt at their improbable good fortune. Confessing at one point to the difficulty they experience even writing Hannah and Manfred in the midst of reading news-stories about “the furious attacks on England,” Stefan describes how “ashamed” they feel “to have here such a perfect life. To look out our windows is simply a dream, the temperature is superb . . . the people spoil us in every possible way, we live quietly, cheaply and the most interesting life—really happy would it not be for you and all the friends and the great misery of mankind.” There is a dazed, blinking quality to Zweig’s delight throughout these letters.

Ernst Feder, a Berlin-born journalist writing for a Rio daily, claimed that no other writer, native or foreign, enjoyed Zweig’s popularity in Brazil, adding that it was impossible to enter any house in the country without finding several of his books, no matter the size of its library. Allowing for an element of hyperbole in Feder’s assessment—he was a good friend of the Zweigs and one of the last to see the couple alive—there’s no question that Zweig was a literary superstar in both Brazil and Argentina. Zweig’s short fictions and long historical biographies, flickering with secrets, abrupt intimacies, and intricately filigreed erotic fantasy, struck home on the continent long before his arrival.

By the mid-1930s, Zweig had been leading a nomadic existence for some time. Estranged from his first wife, Friderike, and convinced that Austria was doomed, he insisted that she sell the former archbishop’s hunting lodge on a hill overlooking Salzburg where the couple had lived and entertained for almost two decades. He abandoned the desk once belonging to Beethoven on which he’d written many of his best-known books, and began selling off his vast collection of rare manuscripts. Foregoing his beloved Paris out of fear that there he would merely “drift into some corner of émigrés,” he moved to London and wrote at the British Museum. Although Zweig tried to persuade himself that England might serve as a permanent alternative to Austria, he lacked the deep gratitude for British values of rational moderation that so moved his friend Sigmund Freud. Whereas Freud made of England’s “sober industriousness” a supreme civilized ideal, Zweig had a taste for cultures with less well-regulated passions. England’s grey skies and emotional reserve left him more prone to fidget than to sublimate.

Given his stellar reputation there and his hunger for some warmer national clasp, we might expect Zweig to have been ready for a love affair with Brazil. In fact, he sailed to South America expecting to find a “hot and unhealthy climate” in which stagnation alternated with “political unrest, and desperate financial conditions.” The entire continent, he imagined, would prove “badly governed, and semi-civilized,” one more tropical backwater for “desperate immigrants and settlers.” But upon arriving in Rio, Zweig received what he called “one of the most powerful impressions of my whole life.” Amidst “one of the most magnificent landscapes in the world,” he found that Brazil offered “quite a new kind of civilization.” Along with “courage and generosity in all modern things”—immediately tangible in Rio’s thoughtful city planning—there were suggestive “traces of a well-preserved ancient culture.” Everywhere he turned, colorful, beguiling surprises gave Zweig “a rush of joy and beauty.” His European arrogance vanished like “so much superfluous luggage.” By the end of his first visit, Zweig was convinced that he’d gazed “into the future of the world.”

Above all else, Brazil seemed to have solved the dilemma of racial and religious coexistence. “Whereas our old world is more than ever ruled by the insane attempt to breed people racially pure, like race-horses and dogs,” he wrote, “the Brazilian nation for centuries has been built upon the principle of a free and unsuppressed miscegenation, the complete equalization of black and white, brown and yellow.” It is easy to see why his emotions were stirred. The image of an exiled Jew drinking in the scene of racially mixed young people parading through Rio’s “orderly, clean-lined architecture” as blood purity was being elevated to cultic supremacy across Europe is poignant. On his first trip to Brazil Zweig had written Friderike, “Brazil is unbelievable, I could howl like a dog at the thought of having to leave.”

When Stefan and Lotte Zweig departed on his second South American junket, in the summer of 1940, Europe was at war. They were both exhausted from the constant moving about. The apparent annihilation of the European humanist values for which he’d worked his whole life jeopardized Stefan’s psychology, even as Lotte’s physical health deteriorated. Zweig’s depression was such that he wrote one friend, “things look so frightful . . . a well-aimed torpedo-shot would to my mind be the best answer.”

Zweig’s letters evoke the nightmarish wartime hurdles to border-crossings, which compelled them to lug about “a whole bag of different papers” including passports, English and Brazilian health certificates, luggage tickets, air tickets, fingerprints, photographs, and lecture invitation tickets. If one document got mislaid, it became impossible, he wrote, to “go forward or backward.” He described himself as “formerly [a] writer, now expert in visas.”

Nonetheless, once again Brazil worked its magic. If possible, his presence with Lotte by his side inspired an even more effusive adulation than the previous trip elicited. Already in his first letter from Rio, Stefan wrote the Altmanns, “Unfortunately I am afraid that Lotte will loose her modesty here since she is always with ambassadors, ministers, photografed in all newspapers.” Within a couple of weeks of arriving, he was invited to deliver a lecture in Sao Paolo that would pay all their expenses for a month in one swoop. “I have no material worries,” he announced, “as the lectures in Uruguay, Argentine, Chile are equally well paid.” In one letter Lotte describes a 24-hour period in which a conference and a book-signing in Rio precede an address before a men’s luncheon and an introduction at a “Jewish charity affair.”

Though Argentina never captured his heart the way Rio did, the Zweigs were a sensation there too. At his first lecture, more than three thousand people attended; police had to intervene to reign in the crowds. Before he reached the lectern, the first thousand seats for the next address had been sold. In Montevideo, Stefan reported, “even the W.C. and bidet are full of flowers for Lotte.” It would have been difficult not to be intoxicated, especially since Zweig’s works were now banned in Austria and Germany.

In Brazil: Land of the Future, Zweig initially appeared to slip into a patronizing tone. He acknowledged that Brazilians evidence “more indolence in the way of living; under the imperceptibly relaxing influence of the climate people develop less impetus, less vehemence.” Then comes the twist. “In short,” Zweig declares, the Brazilians possess “less of just those qualities which nowadays are tragically overestimated and praised as the moral values of a nation.” He goes on to deplore the use of statistics to gauge quality of life. “Judging by these figures the most cultivated and most civilized peoples would seem to be those who have the strongest impetus to production, the maximum consumption, and the greatest sum in individual wealth.” Things get mistier as he tries to identify an alternative measure. He settles for invoking a “peaceful way of thinking” and “humane attitude,” but his main point is that “the highest form of organization has not prevented nations from using just this power solely in the interest of bestiality.”

It is easy to characterize this as a familiar European quest after prelapsarian tropical innocence. Some of this is certainly there, along with a few cringe-inducing allusions to smiling Negros at work in the fields. Yet the tribute Zweig pays to cities like Rio and Sao Paulo is subtler. What he finds most moving in Brazil is ultimately neither the floral vistas, nor the happy laborers, but the way the culture evokes, at least for him, the relaxed, graceful cosmopolitanism that nurtured his own artistic production. As his friend and literary executor Richard Friedenthal noted, Zweig came to believe that the “ancient and old-fashioned virtues of European cultured society . . . gentleness, tolerance, appreciation of spiritual values” had found a “last refuge” in Brazil.

A brief intermediary section of Stefan and Lotte Zweig’s South American Letters treating the time between their two trips to Brazil shows how New York punctured their South American buoyancy. Manhattan revolted Zweig “with its luxury-shops, its ‘glamour’ and splendour—we Europeans remember our country and all the misery of all the world too much.” He found the refugee community even more unbearable. Zweig has sometimes been maligned for neglecting his fellow Jewish émigrés, but these letters refute the charges by showing just how arduously he worked on their behalf to procure support and essential traveling papers. But the correspondence also shows how psychically flayed he felt by the sense that it was never enough. While staying in New Haven, Zweig describes his relief at getting away from all the people “now crowded in New York—the whole Vienna, Berlin, Paris, Frankfurt and all possible towns.”

Notwithstanding his wretchedness in New York, months of indecision regarding their next move ensued. “America has its advantages—libraries, possibilities of income etc—But Brasil—beauty, quiet life, cheap,” he wrote. Finally, Zweig made up his mind to return to “the land of the future.” But in his last letter from New York to Hannah and Manfred, it’s clear how reduced his expectations had become. “Our hearts are not light at all . . . Lotte is physically much better now and perhaps we will have in Brazil a better time: only if this nomadic life would come to an end, I would like to live in a Negro hut in Brazil if I should know if I could stay there.” The Zweigs’ final return to Brazil in August 1941 again supplied a measure of therapeutic calm. Yet, for the first time, Stefan was not swept up by Rio’s charm. Days after arriving, he wrote the Altmanns that he could not continue without books or a home. “We remain Europeans for ever,” he wrote, “and will feel everywhere strangers.” What went wrong?

It is never, of course, the same to set up residence somewhere as it is to ponder a place’s platonic advantages from hotel rooms and airplane cabins. Ongoing headaches with their Brazilian identity documents forced Zweig to recognize that the country had its own bureaucracy. More disturbingly, his Brazil book was being attacked locally for showcasing the country’s exoticism without paying due tribute to its modern achievments. Rumors that he’d been paid by the Vargas dictatorship to write the book further tormented him. Portuguese also defeated the Zweigs. For all their linguistic facility and diligent study, it proved one tongue too many. It can’t have helped matters that once Vargas resolved to throw his country’s fortunes onto the side of the Allies his government banned German newspapers, seized German books, and made it illegal to speak German in public.

Mostly, the Zweigs were simply worn out. In letter after letter, Zweig makes clear that he no longer believes he can outlast the war. The German invasion of the Soviet Union provoked Zweig to write the Altmanns that the war situation would only “become worse and worse for our mankind,” and that “while a younger generation would no doubt live to see better times, I with my ‘three lives’ feel that my generation has become superfluous.”

To escape Rio’s heat and crowds, the Zweigs moved into a bungalow in the Brazilian summer resort village of Petropolis. For a time, they cherished the quiet of their new life. Yet the seclusion they’d pined for soon turned lonely. Increasingly, they fretted away their hours waiting for the next mail delivery. Stefan yearned to launch a major new writing project, perhaps to finally complete his biography of Balzac or magnify his germinal study of Montaigne. The plaintive cry that he lacked the right books rings through his letters.

His mood began to careen like a streetcar off its tracks. One moment, he writes movingly of his and Lotte’s shared love for their new life, and the next he abruptly rails against her “damned asthma, which is somewhat better but every night there are one or two dialogues between her and a dog in a house far away.” Then he lurches again. “Alltogether I cannot tell you happy we are to have left New York where our life did not belong to us and we had all kind of problems, while here we live forgotten and forgetting the time, the world (but not you).” And yet he can’t stop gaping over the change that’s befallen him. At one point he breaks out, “I would not have believed that in my sixtieth year I would sit in a little Brazilian village, served by a barefoot black girl and miles and miles away from all that was formerly my life, books, concerts, friends, conversation.” Lotte struggled to comprehend Stefan’s “black liver,” but found little to grasp beyond the notion she took from their friends that his depression was “not an isolated case but was attacking—and leaving—the different European authors one after the other.”

Gradually, a new note creeps into the Zweigs’ letters. Their most vivid pleasures now involve rekindling the distant past. In a letter to her sister-in-law, Lotte describes teaching herself and the maid to make Palatschinken, Schmarren and Erdapfelnudeln and other ‘European dishes’ . . . My memory . . . is going back further and further.” As time closes in on the Zweigs, they spend their hours reading the classics, taking long walks with their fox terrier, stopping off at the nearby Café Elegante for coffee, and playing chess in the evenings. With their simple pleasures—the traditional Central European dishes at home, the old great books, the uneventful rhythm of their days—it’s as if Stefan and Lotte are striving to recreate a domestic version of the Austro-Hungarian “world of yesterday,” of which he had so evocatively written. But in the midst of heavy rains, tropical mold invades the house and won’t leave their clothes, books or papers alone. They’re kept awake nights by mosquitoes, fleas, spiders and little animals. A pair of snakes appears in their garden.

Zweig’s restrained, deeply moving suicide letter reads at times like a love note to Brazil. It begins with the announcement that “before parting from life of my own free will and in my right mind I am impelled to fulfill a last obligation: to give heartfelt thanks to this wonderful land of Brazil which afforded me and my work such kind and hospitable repose.” There has been much speculation about what, finally, snuffed out Zweig’s will to live. He killed himself just after watching Rio’s carnival, and the contrast between that riotous celebration and the depths into which most of the world was descending certainly gave a further jolt to his anguish. America’s entry into the war in December, coupled with the fall of Singapore, convinced him that there would soon be nowhere on earth free from the contagion of the conflict. But why, really, look for answers beyond the reasons he gave in his letter?

After declaring “every day I have learned to love this country more and more, and nowhere else would I have preferred to rebuild my life from the ground up” he finishes:

After one’s sixtieth year unusual powers are needed in order to make another wholly new beginning. Those that I possess have been exhausted by the long years of homeless wandering. So I hold it better to conclude in good time and with erect bearing a life for which intellectual labor was always the purest joy and personal freedom the highest good on earth . . . I salute all my friends! May it be granted them yet to see the dawn after the long night! I, all too impatient, go on before.

Lotte left no note. But her final letter to Hannah is equally clear. “Going away like this my only wish is that you may believe that it is the best thing for Stefan, suffering as he did all these years with all those who suffer from the Nazi domination, and for me, always ill with Asthma . . . Believe me it is best as we do it now.” President Vargas ordered a state funeral.

Two days after the suicide, the writer René Fülöp-Miller received a letter from Zweig. Zweig encouraged his friend to make a close study of Montaigne, and concluded by quoting him: “In life we are dependent on the will of others, but our death is our own affair. Reputation has nothing to do with it . . . Death is the great homecoming.”

George Prochnik is the author, most recently, of In Pursuit of Silence: Listening for Meaning in a World of Noise. He is completing a novel about Stefan and Lotte Zweig’s American exile.

Suggested Reading

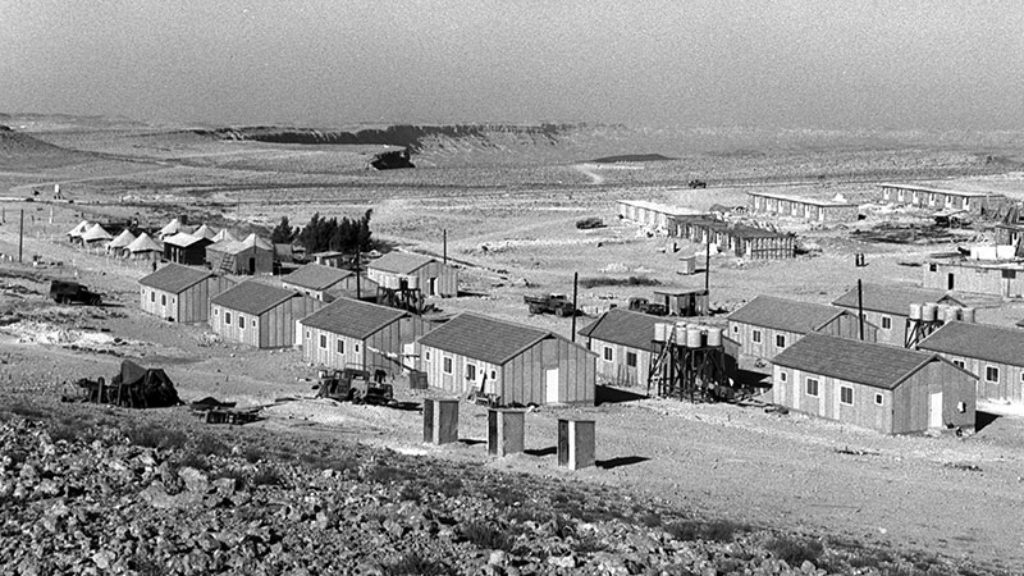

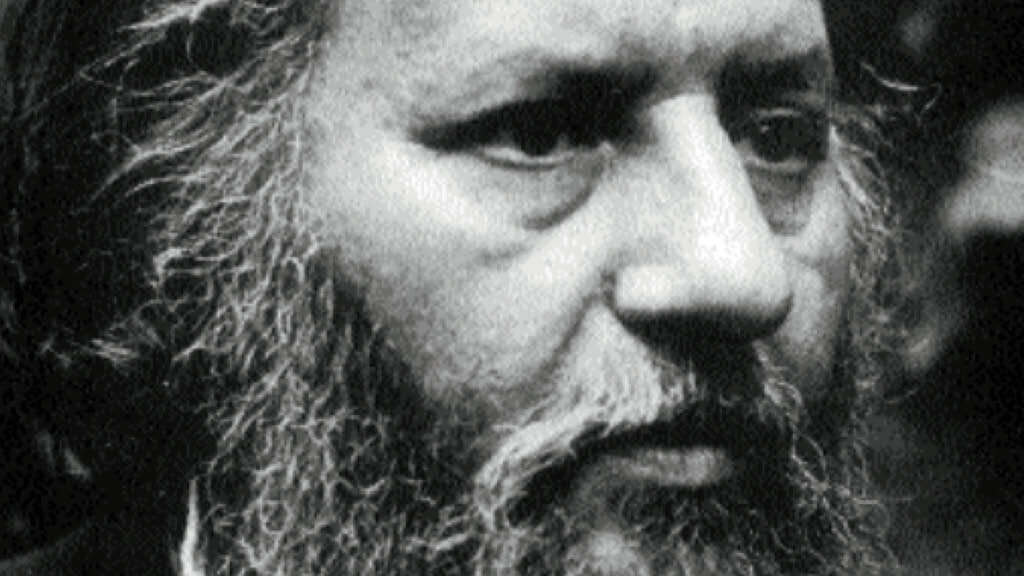

Seventy Years in the Desert

At the 1965 International Bible Contest, David Ben-Gurion posed some of the questions. He also asked two to the entire audience: “How many of you are ready to make aliyah to the Land of Israel?” And then, more specifically, “How many of you are ready to come and live with me in the Negev?”

Leapsniffing through the Vimveil: Avram Davidson’s Fantastic Fiction

Gods in fishbowls, men who are apes, and a Jewish dentist abducted by aliens: the fantastic fiction of Avram Davidson was almost as strange as his life.

Saladin, a Knight, and a Jew Walk Onto a Stage

Outside of Germany, Nathan the Wise is one of those works more often read than performed, and more often read about than actually read.

Dust-to-Dust Song

Nelly Sachs was 50 years old when she fled the Nazis with her mother in 1940. Few would have perdicted that she would receive the Nobel Prize for Literature twenty-six years later.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In