Letters, Spring 2017

Uninspired Cousins and Jewish Excellence

As a footnote to Eric Cohen’s account of David Ben-Gurion as a young man (“Three Portraits of Jewish Excellence—at 29,” Winter 2017) and the paucity of attendees at his Zionist lectures in North America: My maternal grandfather, Nathan Green, was a first cousin of Ben-Gurion. (Green, not Gruen, was the name under which the family came to the United States from Płońsk in 1906.) My mother, the youngest of four children, was 12 years old when Ben-Gurion arrived in New York in 1915. She recalled that during his stay he was constantly “dragging”—to use her word—her father to one meeting or another. (Also, he wore “funny caps.”) Nathan was a Hebrew-school teacher and shamus of the local shul in Harlem. I don’t know whether he had any interest in Zionism, but neither he nor any of his children were inspired to make aliyah.

Raymond S. Hack

Coconut Creek, FL

Eric Cohen’s essay on Leo Strauss, Joseph Soloveitchik, and David Ben-Gurion at the age of 29 is an intriguing entry into the literature on adult personality development, the virtues and the inevitable messiness of even the most successful human lives.

Early on in his essay, Cohen writes that “if these three Jews sat together in a seminar room, they would surely disagree on many things, including the most ultimate things. But they all led lives of Jewish consequence.” This is undoubtedly true (though extreme partisans of each of their approaches might deny it), but it does leave me with a question that I’m not sure Cohen directly addressed. I take it that one of those ultimate things upon which they would have disagreed is the question of how a Jew should live in the modern world. But beyond that deep theological, political, or theological-political problem, did they share anything distinctively Jewish? Should we merely describe each of them as bringing their different (and universal) human capacities to the modern Jewish predicament, or are there virtues that are distinctly, albeit not uniquely, Jewish, which they possessed in common? Is there something about Judaism writ large, or perhaps early-20th-century Ashkenazi Jewish culture, that lends itself to the inculcation of particular human excellences?

Dr. Michael Stein

Los Angeles, CA

The Menorah and Its Flame

Elizabeth Shanks Alexander’s review of Steven Fine’s The Menorah: From the Bible to Modern Israel (“The Lamp of Zion,” Winter 2017), and presumably the book itself, overlooks a critical iconographic element that would argue, perhaps conclusively, for the lack of any influence between the image sculpted on the Arch of Titus and the iconic deployment of the Temple menorah in Jewish art from late antiquity through the Middle Ages. What’s more, this distinction would indicate that the menorah itself, qua vessel, is hardly the main object of spiritual/eschatological import, but is merely the medium thereof. As far as I know, without exception, in every Jewish depiction of the menorah, on late-antique frescoes, in glass, or as rendered in illuminated manuscripts—and this includes carpet pages of medieval Jewish bibles—the menorah is lit. And not only is it lit, but with few exceptions (the Roman gold glass depicted in the review being one of them) the flames on the left and right of the menorah are pointed toward the central one, in keeping with the biblical instruction of mul p’nei ha-menorah. Hence it is clear that for the Jewish icon, it is not the vessel itself that is of sacred value (as would be the case, for example, regarding a Jesus-less cross in medieval Christian art) but rather the flames themselves which are of spiritual and eschatological significance—the vessel merely being a necessity, since flames require a source of fuel.

In fact, the only example of a flameless menorah in a Jewish artifact, to the best of my knowledge, is that in the Spanish Jewish Cervera Bible, which depicts the menorah of Zechariah’s vision being fed by two olive trees.

Jacob J. Gross

Jerusalem and Budapest

via email

Elizabeth Shanks Alexander Responds:

I agree with Mr. Gross, but only to a point. He suggests that “the image sculpted on the Arch of Titus” did not influence “the iconic deployment of the Temple menorah in Jewish art from late antiquity through the Middle Ages.” Undoubtedly, he is correct in this assessment. As I noted in the review, “For many years the arch menorah was inaccessible to the majority of the world’s Jews. It was in Rome, and they were elsewhere.” After 70 C.E., Romans and Jews would have, for different reasons, regarded the menorah as a potent symbol of the destroyed Jerusalem Temple and its defeated people. There is no need to assume that the Roman depiction of the menorah on the Arch of Titus led to or caused its importance among Jews. It is the next step in Gross’s argument that gives me pause. He argues, on the basis of late antique and medieval images of the lit menorah (with flames pointing towards the center), that “it is not the vessel itself that is of sacred value . . . but rather the flames themselves which are of spiritual and eschatological significance.” Visual (and literary) evidence supports his assessment from the 4th or 5th century C.E. For example, Gross’s claim about the flames symbolic meaning is corroborated by the 6th-century Yannai poem lamenting the extinguished flames of the lamp of Zion. Gross’s claim about the insignificance of the menorah-as-object falters, however, in the face of late-antique images that depict a flameless menorah: a Hasmonean coin (37 B.C.E.), a footed ashlar from Magdala (1st century C.E.) and a synagogue chancel screen from Ashkelon (5th to 6th century C.E.). A number of visual sources depict the menorah, with and without flames, alongside other Temple vessels (e.g., the showbread table and firepans) and other ritual objects (lulav, etrog, and shofar). It seems reasonable to conclude that the menorah compelled interest initially as an object among other Temple objects and then later as a vehicle for its redemptive flames.

A Joke Retold

In Joseph Epstein’s review of two books on Jewish jokes (“Jokes: A Genre of Thought,” Winter 2017), he retells a story that his friend the sociologist Edward Shils told about the three untruthful synagogue members exposed by the rabbi. This is actually a variant of the story Sholem Aleichem records as being told to him at his own expense. A Jewish traveler at a train station is persuaded to miss the last train before the Sabbath in order to complete a minyan. The traveler is put up for the night, urged to taste his host’s wife’s cooking, and so on for several days. When the traveler finally leaves, he is presented with a detailed bill. The traveler is outraged but agrees to go to the town rabbi to settle the case. The rabbi solemnly rules that he must pay. When the traveler grudgingly hands over the money, the local man indignantly refuses to take it. When he asks what the demand for payment was all about, he is told—“I didn’t want you to leave town without seeing what kind of rabbi we have.” Sholem Aleichem was, of course, for three years a rabbiner (state-appointed rabbi) in the town of Lubny.

Solon Beinfeld

via jewishreviewofbooks.com

Romcom

It was surprising and, I suppose, edifying to learn from Sarah Rindner (“Waiting for Moshe Right,” Winter 2017) that web comedy is now being made of the situation in which I find myself (Orthodox and single in Manhattan), and from Alan Mintz’s review of Naomi Seidman’s new book (“What’s Yichus Got to Do with It?” Winter 2017) that the “Jewish marriage plot” is a key element in the creation of the modern Jewish world. But do either of them have any practical suggestions? Perhaps they can co-host a Jewish Review of Books salon for singles on the Upper West Side.

Name Withheld

New York, NY

Remembering Salonica

Congratulations to Professor Devin Naar for his splendid, though disturbing, article, “Memory and Desecration in Salonica” (Winter 2017). He is not only a fine academic historian but also a wonderful custodian of our memory (and I agree with him that Judeo-Spanish is the correct term for the spoken language of our ancestors).

Dr. Michel Azaria

Judéo-Espagnol A Auschwitz (JEAA)

Paris, France

Suggested Reading

Total Eclipse of the Brakha

Do we make a blessing on a solar eclipse? Well, that depends if eclipses are evil or not.

Vive la Differénce! A Rejoinder to Joshua Holo

The final installment in an exchange between Elli Fischer and Joshua Holo about Michael Chabon's controversial commencement address at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion.

In Brief, Fall 2010

Hirsch’s poems, Illion’s lions, short prayers, Tommy Lapid & more.

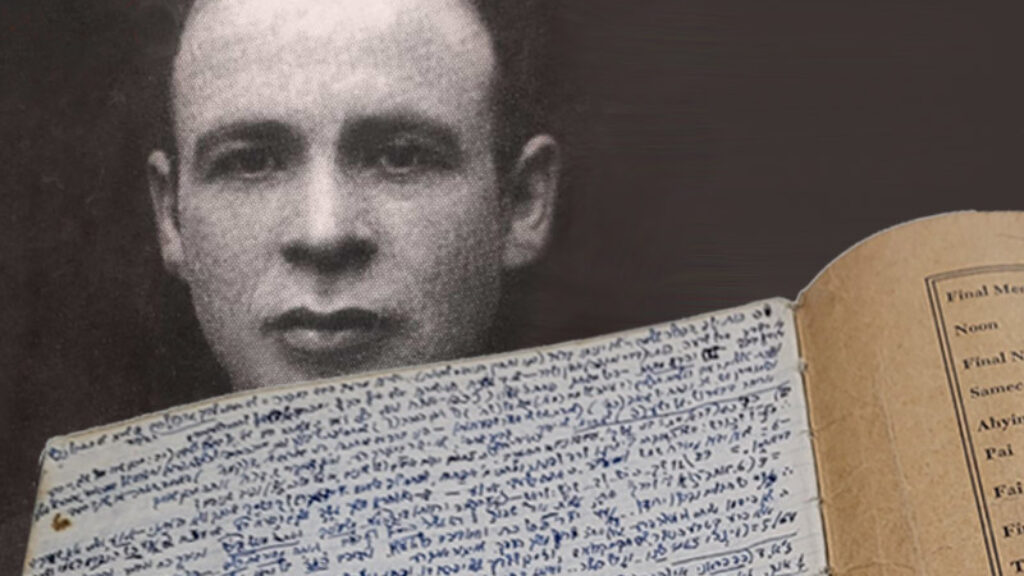

Think Over My Lesson and Try to Destroy It

When Levinas met a vagabond called Chouchani, he told a friend, “I cannot tell what he knows, all I can say is that all that I know, he knows.” Now that we have dozens of Chouchani’s notebooks, can we finally know what he knew?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In