Of Memory, History—and Eggplants

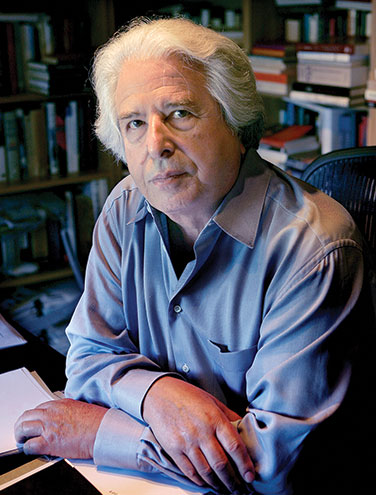

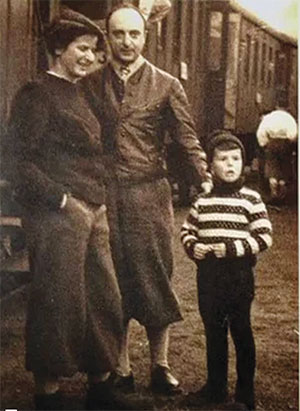

Saul Friedländer’s poignant, elegantly written memoir When Memory Comes was published originally in French in 1978 (and in English in 1979). There, in fragmented form and with almost unbearable restraint, written, as Leon Wieseltier put it, in a language that seems “armored against the dissolution it describes,” Friedländer recounted his tale of survival under the Nazis and its lasting effects on his dismembered life. Holocaust memoirs were gaining wider popular attention just then, but the elegance and intellectual probity of Friedländer’s writing endowed it with an especially polished, alluring, and painful quality. Moreover, here was a widely read memoir that differed from other famous works by luminaries such as Elie Wiesel, Primo Levi, and Jean Améry. For one thing, unlike those men who lived through the camps, Friedländer survived the Holocaust far away from Eastern Europe, hidden as a child in a French Catholic boarding school. This experiential difference itself became an object of his stylish retrospection, part of an ongoing split of being, that he described thus:

The veil between events and me had not been rent. I had lived on the edges of the catastrophe; a distance—impassable, perhaps—separated me from those who had been directly caught up in the tide of events, and despite all of my efforts, I remained, in my own eyes, not so much a victim as—a spectator. I was destined, therefore, to wander among several worlds, knowing them, understanding them—better, perhaps, than many others—but nonetheless incapable of feeling an identification without any reticence, incapable of seeing, understanding, and belonging in a single, immediate, total movement.

There is yet another difference. Wiesel, Levi, and Améry were writers who achieved their deserved fame mainly for having given literary expression to the experience of living through the Holocaust. What sets Friedländer apart is that he also became a great chronicler of the European Jewish catastrophe, both its pained subject and respected historian.

When Memory Comes was about the painfully willed task of recollection, of dredging back to consciousness memory of events long repressed, self-reflexively revealing the hidden effects that traumatic experience continued to exert many years after the event. No wonder that the book’s title and epigraph were drawn from Gustav Meyrink’s observation that, “When knowledge comes, memory comes too, little by little. Knowledge and memory are one and the same thing.”

When Memory Comes has just been republished together with Friedländer’s new, and far longer, memoir, Where Memory Leads, which picks up where the earlier volume left off. His new memoir is similarly concerned with the dynamics and problems of retrieval. But, then, there is memory—and there is memory. The profound and traumatic issues, the unique and highly personalized stakes of memory that lie at the heart of the first volume, give way to the irritating, quotidian issues of memory that afflict all of us at a certain stage of our lives. The painful grandeur, the tragic tale of an innocent child swept into a cataclysmic event, the other-worldly quality of the first volume has been replaced by an ageing man’s quite normal struggle simply to remember names and words.

Where Memory Leads begins with Friedländer’s bewildered attempt to remember the Hebrew word for aubergines (that is, eggplants), which his wife Orna (to whom the book is dedicated) eventually reminds him, to his great relief, is hatzilim. “Starting a book of memoirs with an episode of memory loss may seem like a joke. It is not,” Friedländer writes. For, as he states, “I started writing these reminiscences after my eighty-first birthday, under the constant threat of some loss of memory.” The contrast between the first volume’s recollection of a violent and abnormal repressed world and the ordinary experiences recounted in the second could not be greater.

One’s reading of an autobiography is almost as colored by one’s own prejudices, perceptions, and experiences as the writing of it. This is especially so with regard to the memoirs of someone with whom one is acquainted. I must therefore add a personal note here that informs my rather complicated response to these volumes. I first met Saul Friedländer in the mid-1980s when he had already acquired a degree of international fame and I was just beginning my academic career. Even in the midst of the intimidating professorial atmosphere of Jerusalem’s Hebrew University, Friedländer possessed a special aura. In retrospect, I suppose there were numerous reasons for this. Here was a man who was not only a famed literary survivor but a master of the historical craft, engaged in the study of the greatest Jewish catastrophe of all time and who already then acted as a kind of protective custodian against the intellectual and political forces seeking to undermine, elide, or even eradicate the magnitude of that event. There was, moreover, a kind of charisma in his authoritative and rather inaccessible bearing. And, of course, his cultured French manner, his “European” style and sensibility seemed to set him apart from his less manicured Israeli colleagues.

I am not claiming that this is how he really was, but it is how I perceived him. Why is this relevant? In part because, at least initially, I found the discrepancy in style and substance between the first and second memoir both jolting and disappointing. But of course my expectation that the second volume would possess the same resonance as the first was entirely unrealistic and patently unfair. How could the second volume of a life (however interesting and successful) lived in the late 20th and early 21st century, within the familiar confines of a reality similar to our own, resemble the first volume, with its chilling, other-worldly, almost sublime, character rendered in an elegant and fragmentary form? Where Memory Leads relates sequences that take place in real time; there is no episodic interspersing of the tale with other earlier fragments, none of the pyrotechnics of emplotment that characterized the first memoir and that makes his later historical work so originally remarkable. Moreover Where Memory Leads, quite unlike When Memory Comes, is mainly rendered in a prosaic key. One simply does not expect Saul Friedländer to use idiomatic expressions like “dead men walking” or “what the hell” or to speak about “schlepping” his suitcase. There are equally jarring moments in the substance of what he has to tell us. It is not easy to come to terms with an idealized figure who now confesses to much youthful womanizing, responsibility for an abortion, emotional distance as a father, a late-life divorce, and a remarriage in—of all places—Las Vegas!

Of course, the fault here lies not in the book but in my own childish expectations. It does not take much insight to realize that even survivors, and even those who are polished historians, are human, all too human. Obviously, in a work subtitled My Life not everything will be about trauma and the abyss; there will also be what the Germans call Alltag, the everyday aspects of a lived life. For all that, the candidness of these confessional moments comes as a considerable surprise. This is because Friedländer is known (and starkly describes himself) as a very distant, self-protective person.

This tension—between the quotidian on the one hand and an abiding reserve and unease on the other—is palpable throughout the memoir. Friedländer relates in some detail his early anxieties and medications, his claustrophobia and agoraphobia, his emotional paralysis and restless travels. The source of all of this is self-evident. For all the apparently ordinary episodes and the everyday tasks and events related in this book, Friedländer confesses that, “People who, like me, lived their childhood under catastrophic circumstances, may have built a ‘normal’ exterior. Yet, no matter how ornamented the façade may appear, some flaw invariably remains at the very core of their personality.”

In Kafka-like manner, Friedländer—who describes Kafka as his “revered compatriot” and who recently published a controversial interpretive biography of the famous Czech author—describes his condition as that of “an insect whose antennas had been torn off.” That surely is not unrelated to the many names that have either been imposed upon him or that he has voluntarily adopted: Pavel, Paul, Paul-Henri-Marie Ferland, Shaul, and Saul reflect the different circumstances and stages of an uprooted life in Czechoslovakia, France, a Catholic seminary, Israel, and America respectively. No wonder, then, that Friedländer reports an abiding longing for community, yet, typically, he adds: “as much as I craved to belong, I feared it. . . . Over the following decades, a kind of seesaw between these two opposing drives—fervent commitment on the one hand, constant search for an escape route on the other—would come to define most of my life.”

For all that, Friedländer seems to possess a knack for reaching high places almost effortlessly through a combination of contacts, charm, and great talent. This applies not just to the academic world but to an interesting pre-university professional life. Two examples must suffice. Through various friends he was introduced to Nahum Goldmann, the colorful head of the World Jewish Congress, and acted as his peripatetic secretary for two years. Then, in 1960, while Friedländer was still a relatively recent immigrant (he had sailed to Israel on the ill-fated Altalena), his friend Shabtai Teveth made a call to Shimon Peres, and he was offered a government job. In those highly informal days, with virtually no clearance or fanfare, he became “Head of the Scientific Office of the Vice Minister of Defense.” In a dazzlingly short time, he was part of the secret Israeli nuclear program. “There I was then, inside the holy of holies of the Israeli defense establishment,” he tells us, “included in a project surrounded by rumors but so secret that, in 1960, even Foreign Minister Golda Meir did not know the crucial details I was privy to.”

The memoir jacket describes Friedländer as an award-winning “Israeli historian.” This is true, though characteristically, in no straightforward way. Friedländer has a steadfast Zionist commitment but one that, as he notes, was “nonbinding as far as life in Israel went.” His relation to the country combines a basic loyalty with a complex critical position. The commitment obviously arises from his wartime experience and the many years he lived in Israel, but also to his generation’s grasp as to the historical magnitude of the very creation of the State (one that is perilously disappearing today). Thus on his participation in the nuclear undertaking, he writes: “To this day, I do not regret having belonged, albeit briefly, to a project that, ultimately, may be the only guarantee of Israel’s survival.” Three decades later, during the 1991 Gulf War, he flew back to Israel. “It was a gut reaction, an imperative expression of solidarity, although the danger was minimal and the missiles did not hit any of their targets.” His interests and passions in far-away, almost exilic, Los Angeles remain closely linked to the country and its culture. Nowadays, he writes, “I do little else than follow Israeli politics,” and it is that country’s literature that he now mainly reads (albeit always in translation; although fluent in Hebrew, he confesses, that he “never quite enjoyed reading books in Hebrew, nor have I ever written a book in Hebrew”). To this day, he and his wife Orna toy with the idea of returning to the country. The energy and creativity of Israel, the family and friends (none of whom live in California) are all tempting, but inertia and a distaste for the current politics of the country keep them from doing so. “Going for longer stays in Europe and in Israel,” Friedländer states, “may be the only viable solution at this stage.”

If his Zionist commitment is clear, so too are Friedländer’s grave and long-standing doubts about the country’s direction. This includes a dose of heavy self-criticism. Following what he describes as the quasi-messianic exaltation that followed Israel’s victory in the June 1967 war, he admits that “in my heart of hearts I shared the euphoria. . . . And yet, that I, who of all people should have understood what occupation does to the occupied and to the occupier, didn’t see any ‘writing on the wall’ embarrasses me from hindsight.” Even earlier, unsettling critical intuitions were at work, although at the time he quickly repressed them. In 1958–1959, when Friedländer was working with Nahum Goldmann, he visited some outlying Arab villages:

One image remains in my mind as a perfect expression of abject submission and humiliation. . . . The mayor and his aides received us with coffee and sweets. Two portraits were hanging above his desk: on one side, that of the founder of Zionism, Theodor Herzl; on the other side, that of the founder of state, David Ben-Gurion.

For many years now Friedländer has been a staunch critic of what he calls Israel’s “misguided policies.” He quotes with relish the well-known witticism that the obdurate former Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir was even smaller than he looked, and he is a passionate advocate of the two-state solution. Yet he is honest enough in admitting that in the years immediately following the 1967 war, he essentially adopted the official Israeli position and patronizingly advocated “autonomy” for the Palestinians. He dubs his worries regarding that war and its aftermath as essentially “pseudo-moral.” Now he is much more pained, even outraged: “How,” he wonders in the final chapter, “could I get out of my mind that Jews in Israel burned a Palestinian alive?”

Having taught over the years at universities in Geneva, Jerusalem, and Tel Aviv, Friedländer eventually settled down in the history department of UCLA. As an Israeli professor teaching in an increasingly anti-Israel university atmosphere, he finds himself in a familiar quandary, caught in the tension between commitment and criticism. Of this dilemma, he writes:

Criticizing Israel’s policies is not only justified, it is necessary. However, questioning Israel’s right to exist is a very different matter. Sometimes one gets the feeling that, in the American academic environment, the first attitude easily leads to the second one. As for the second attitude, it often smells of more than a whiff of anti-Semitism.

Readers will be mainly drawn to this book in the knowledge of the exceptional quality of his work on the Holocaust and the central custodial role Friedländer has played in the charged moral, political, and intellectual issues and stakes surrounding it. In the last third of the book, Friedländer highlights some of the key moments in this career, the evolution of his work, the polemical tussles, and sketches sharp portraits of his many colleagues, friends, and adversaries.

Friedländer’s decision to become a Holocaust historian came relatively late. In retrospect—given the upheavals he had experienced—a period of considerable latency was inevitable (a topic on which he has written with much insight). As he describes it, Friedländer almost stumbled onto the topic. In the early years in France and in Israel he writes that, “I don’t recall ever reading historical books about Nazi Germany or the war; it simply didn’t occur to me.” Moreover, when he did finally begin to research National Socialism he studiously avoided the criminal aspects of the regime. His doctoral dissertation, published in 1963, was a closely documented study of Nazi policies toward and perceptions of the United States. But of course, with time, it was the Third Reich’s distorted perceptions and murderous policy toward the Jews that have formed the center of his work. Despite his many other cultural predilections, it is indeed this work and what Friedländer calls his “core identity” that have become inextricably intertwined. “I am a Jew, albeit one without any religious or tradition-related attachments,” he writes, “yet indelibly marked by the Shoah. Ultimately, I am nothing else.”

His first foray into the subject was a work on the relationship of the Catholic Church to Nazism. This 1964 documentary study of Pius XII and the Third Reich, while cautioning that there was not sufficient archival evidence to render any definitive pronouncement, nevertheless posited the question as to how, by the end of 1943 the Church could (even given its anti-Bolshevist impulses) continue to wish for victorious resistance in the East “and therefore seemingly accepted by implication the maintenance, however temporary, of the Nazi extermination machine?” Impeccably documented, written with his characteristic scholarly restraint, the only clue to Friedländer’s personal odyssey lay in his telling dedication: “To the Memory of My Parents Killed at Auschwitz.”

Three years later Friedländer published Kurt Gerstein: The Ambiguity of Good, a study of an extra-ordinary German who, in a rare act of moral conscience and heroic anti-conformity, joined the SS in order to try to impede—and inform the world of—the “Final Solution.” Friedländer also later turned to psycho-history in a study, published only in French, that posited Nazi anti-Semitism as a kind of collective psychosis. He soon quietly abandoned this hypothesis. Nevertheless, he has always insisted upon the psychological dimension as a necessary factor in the murders and chided other historians for trying to subsume it under explanatory categories such as ideological motives or institutional dynamics. Friedländer’s psychological acuity has been present throughout his work. In Reflections of Nazism: An Essay on Kitsch and Death (1984), he identified a new set of trends in Western culture that reflected a disturbing attraction to Nazism. “Attention,” he wrote, “has gradually shifted from the reevocation of Nazism as such . . . to voluptuous anguish and ravishing images. . . . Some kind of limit has been overstepped and uneasiness appears.”

All of these issues came together in Friedländer’s participation in the intense international controversy that became known as the Historikerstreit (historian’s debate). In 1985 the German philosopher and historian Ernst Nolte published a provocative article in a rather obscure publication that outlandishly described the National Socialist treatment of the Jews as a kind of defensive action taken in response to a Jewish “declaration of war” against Germany (an assertion which, surprisingly, was relatively neglected in the heat of the debate). Nolte went on to propose that modern genocide was a Communist invention, not a German one, and that the Gulag was “more original” than Auschwitz. “Was not,” he rhetorically asked, “the class murder of the Bolsheviks logically and factually prior to the race murder of the National Socialists?” This was a move which Friedländer (and others, including Jürgen Habermas) regarded as a kind of attempt to “normalize” German identity by placing the Nazi past within a relativized comparative framework, rendering it somehow more empathically accessible and comprehensible. While Friedländer does not really rehearse the arguments in great detail in his memoir, he does reveal that the origins of the explosive debate were in a dinner party that he attended at Nolte’s home when he walked out as a result of Nolte’s clearly anti-Semitic questions and comments to him. For years, this has been a kind of circulating underground story, which Friedländer confirms in detail.

As scrupulous a historian as Friedländer undoubtedly is, the personal and the professional have always been deeply intertwined. Actually, it was precisely on this sensitive point that the German historian Martin Broszat challenged Friedländer a few years after the historian’s debate. In their riveting correspondence, previously unacknowledged tensions between so called “Jewish” and “German” perspectives on the war were aired. Broszat argued that “Jewish” historiography perforce had to be “victim” history, mournful, accusatory, and ultimately mythical rather than scholarly and scientific. Friedländer sharply retorted that the German context created as many problems for the descendants of the perpetrators as it did for the victims. “Why,” Friedländer asked, “would historians belonging to the group of perpetrators be able to distance themselves from their past, whereas those belonging to the group of victims would not?” (It was revealed only later that Broszat had been a Nazi Party member as a young man.)

That debate demonstrated that Friedländer has always been aware that a “purely scientific distancing from the past . . . remains . . . a psychological and epistemological illusion.” Of course, throughout, he had acknowledged the need to balance “memory” with scholarly integrity and historical research. As he puts it in the memoir:

Memory goaded me on, but at the same time its impact had to be acknowledged. I wasn’t writing on the moon; I was a Jew writing the history of his time, of his family, of the Jews of Europe on the eve of their extermination. I had to keep constantly aware of my subjectivity, remain on guard as much as possible, and show that even the victims “and their descendants” . . . were able to write that history.

I would argue, it is precisely this tension—the attempt to write objectively but as a Jew “writing the history of his time, his family”—that gives Friedländer’s work its peculiar energy and quality.

In the influential 1992 anthology Probing the Limits of Representation: Nazism and the “Final Solution,” which Friedländer edited, he initiated the (still ongoing) discussion of the limits and possibilities of historical representation, especially of the Holocaust. Friedländer’s position is, as expected, of considerable sophistication. On the one hand, he clearly rejected the postmodernist notion that “reality” is essentially a function of narrative emplotment and rhetorical choices, arguing instead that it is “the reality and significance of modern catastrophes that generate the search for a new voice and not the use of a specific voice which constructs the significance of these catastrophes.”

Yet it was precisely his sensitivity to the limitations of narrative—how does one include all the voices of those involved in a complex historical event?—and the limits of conventional historical representation that lend his work its special high modernist quality. His two-volume magnum opus Nazi Germany and the Jews (released 1997 and 2007 respectively), which was motivated by a “recurrent sense of not having fulfilled what I felt as a deep obligation,” reflects these sensitivities and innovations. Friedländer’s narrative weaves into the more conventional themes of causality, function, structure, and ideology the voices of those implicated in the murderous events of those years. The contemporary reactions, feelings, and fears of perpetrators, bystanders, and, above all, victims punctuate his account. While this inclusivity is crucial for Friedländer, there is another vital component in his work: the need to disrupt what he regards as the coldness of distanced conventional historicalperspective. The victims’ “unexpected ‘cries and whispers,’” he writes, “time and again compel us to stop in our tracks.”

While scrupulously adhering to the tools of historical research, Friedländer succeeds in conveying what he calls the “unbelievability” of these events. The double aim of the work, he tells us in the memoir, was to write “as precise a historical rendition as possible, and to at the same time re-create for the reader a momentary sense of disbelief that history has a tendency to eliminate in the case of extreme events.”

Where Memory Leads relates the broad outlines of Friedländer’s academic career but it does not—and, in fairness, could not—come close to capturing the sterling nuanced quality and character of the actual work. The memoir should be a goad to readers to turn to the work itself, in particular his magisterial two-volume history.

Throughout Where Memory Leads there are intimations of natural decline and an approaching end. The final chapter is entitled “The Time That Remains.” Why, one wonders, would this cosmopolitan Israeli European want to end his days in the far reaches of California? For he makes any number of biting comments expressing his sense of exile in Los Angeles: its blandness, its real and symbolic distance from the familiar domains of his sensibility. The only heritage that has left no imprint on him, he proclaims, “is the American one with its added Los Angeles hue.” Yet, perhaps, given the multiple plays of identity in Friedländer’s life, this is not so strange. “There is,” he writes, “some logic in my having ultimately landed in the simulacrum of a real place, in a city that . . . does not touch you, take hold of you.” Perhaps, he suggests, he “found in Los Angeles a saving grace in the relative absence of that [Holocaust] past in the environment and common discourse.”

Yet, beyond his alienation from the American culture, Friedländer is a great admirer of the country’s core values. In a phone call to another Israeli historian and “exile,” Omer Bartov, Friedländer relates that he wished Bartov a happy Thanksgiving to which the latter replied, “‘Yes, thank God for America!’ I never forgot that unexpected answer, and, indeed, I often feel the same.” (One imagines that the new Trump era has given him some pause.)

Despite all that he has experienced, Friedländer seems to have achieved at least a sliver of domestic contentment and peacefulness. The book gives an affectionate account of his scattered faraway children and grandchildren in Tel Aviv and Berlin. The work ends almost poetically with a moving portrait of the family puppy, Bonnie: “We cherish that innocent, trusting, loving, little being . . . she immensely enjoys being chased around . . . Yet after a while, she will be tired, fall asleep, faintly snore, and suddenly twitch as she dreams.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Blood Delusion

While the blood libel was rooted in Christianity, it also accused Jews of practicing precisely the opposite of what Judaism itself teaches, namely, not to consume blood.

Peace, Plan B

Secretary of State John Kerry's attempt to get Israel and the Palestinians to a final status agreement was never going to work. What will?

Religion and Power

Rabbi Sacks, who is in the end an optimistic thinker, sees a process of internecine violence leading to religious moderation happening within Islam now.

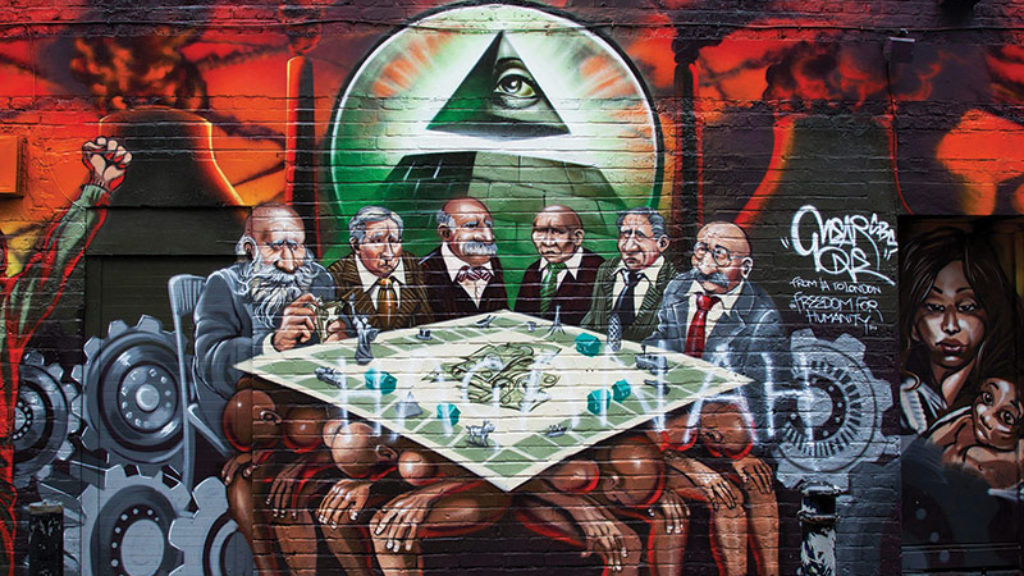

Jews Not without Money

Jews, Money, Myth, at London's Jewish Museum, normalizes the Jewish relationship with money without negating those factors that made this particular historical association especially fraught.

ezuesse

The "new Trump era" is the flip-side and responsive repudiation by the silent victims of the "Obama era." It is called "democracy" that the failures, abuses and evils of one Presidency, having so alienated and smothered a considerable portion of the electorate, can be voted out of office by a brash and irreverent candidate bringing a whole new broom into play. This is indeed still America, and Trump addresses himself to a whole population that remains as alien to the fashionably alienated university campus as story-book Marsians, but who have been the foundation of the American ethos from the start.

It is a pity that Ascheim mars his excellent review, written with remarkable grace and intelligence, with a nod to topical left populism at the end, to show that he is 'one of the club of the righteous.' One gets tired of this sort of so frequent elitist sloganizing ideological "virtue-signalling."