The Lost Textual Treasures of a Hasidic Community

After World War II, the Allied Forces set up the Offenbach Archival Depot to sift through the several million stolen Jewish books that the Nazis had not destroyed. Led by Colonel Seymour J. Pomrenze, the small team tried to trace the origins of this almost uncountable mass of books, and, to the minimal extent possible, to return them to their owners. In order to do so, they created a catalogue of library markings and stamps. This two-volume album, now held at the University of Chicago’s Regensburg Library, provides a detailed, poignant picture of the lost world of Jewish book collections, and indeed Jewish culture, in Europe before World War II. Stamps from major centers of academic research, yeshivas, and private collections lie next to stamps from Jewish kindergartens and cheders across the pages.

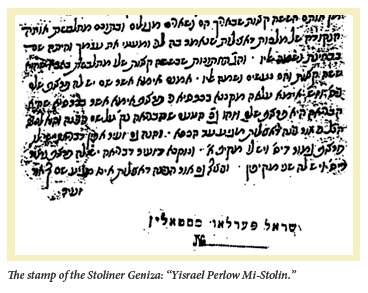

Leafing through it a few years ago, I came across a stamp that looked like it had come from the lost archive of the Stoliner Hasidim. This, together with the fact that at least two rare kabbalistic manuscripts known to have been part of the Stoliner collection have surfaced in the murky world of Hebraica dealers—one bought by the Stoliners themselves, the other by the Jewish National Library of the Hebrew University—raises the possibility that their textual treasures are not irrevocably lost. If the rare manuscripts and books carefully collected and preserved by the Stoliner Hasidim from the early 19th century until the 1930s were recovered, even in part, it would be one of the greatest Hebraica finds of our times. It would also serve as a small but real consolation to the Stoliner Hasidim, whose community, along with the rest of Belarusian Jewry, was devastated during the war.

The geniza, or archive, of the Karlin-Stolin (the Stoliner) Hasidim first came to wide public notice just as it was about to disappear. In 1941, Gershom Scholem published his classic Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. In its final chapter, Scholem announced a discovery:

An unexpected find has provided us with a useful hint concerning the relations between the [old and new] forms of Hasidism. In the biographical legends concerning the life of the Ba’al Shem [Tov] . . . a good deal is said about a mysterious saint, Rabbi Adam Ba’al Shem, whose mystical writings the Ba’al Shem was said to have treasured . . . Only recently, however, we have come to learn of a curious fact . . . the descendants of Rabbi Solomon of Karlin have in their possession a great many Hasidic manuscripts and other documents . . . I learned to my great surprise that there is among other documents a voluminous manuscript called Sefer Ha-zoref, written by Rabbi Heshel Zoref of Vilna who died in 1700, just when the Ba’al Shem was born . . . Now all this amounts to no less than the fact that the founder of Hasidism guarded the literary heritage of a leading crypto-Sabbatean and held it in great esteem. Apparently we have here the factual basis of our Rabbi Adam Ba’al Shem.

To understand Scholem’s excitement, one needs to know that Scholem believed in the enduring influence of the movement that grew up around the failed 17th-century messiah Shabbtai Zevi, as well as a bit about the story of Rabbi Adam.

Shivchei Ha-Besht (In Praise of the Ba’al Shem Tov) is an early 19th-century collection of tales about the founder of Hasidism that circulated during his lifetime and after his death in 1760. Early in the book, we are told of a kabbalistic master who identified the young Ba’al Shem Tov as his spiritual successor.

Before Rabbi Adam’s death, he commanded his only son, “I have manuscripts here that hold the secrets of the Torah, but you do not merit them. Search the city called Okopy and there you will find a young man of about 14-years-old whose name is Israel ben Eliezer (the Ba’ al Shem Tov). You will hand him the manuscripts for they belong to the root of his soul.”

Later, the reader is told that the Ba’al Shem Tov sealed Rabbi Adam’s manuscripts beneath a stone in a mountain.

Thus, Scholem thought that he had discovered (albeit, by proxy, as we shall see) the secret manuscripts and historical figure behind the legendary Rabbi Adam in Heshel Zoref, whose work had been owned by the Ba’al Shem Tov himself and carefully preserved by the Stoliner Hasidim. Maybe his enthusiasm accounts for the incidental sloppiness with which he announced the discovery: the rebbes of Karlin-Stolin were descendants of Rabbi Aharon, not Rabbi Solomon, of Karlin, and their carefully curated manuscript collection of materials from Poland and Safed was assembled in the 19th century, not the 18th .

Scholem never did get a chance to actually see the Stoliner manuscript of Sefer Ha-zoref. Although the lectures upon which the book is based were delivered at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in New York in 1938, Major Trends was published shortly before the Nazis confiscated the Stoliner archive and consigned its custodians to death.

Although the lost archive is of extraordinary historical value regardless of the actual nature of how much Heshel Zoref’s book influenced the early Hasidic movement, the story of how Scholem came to make his announcement is a window into the tense, fascinating, and not altogether edifying relationship between Hasidim and secular historians in interwar Poland.

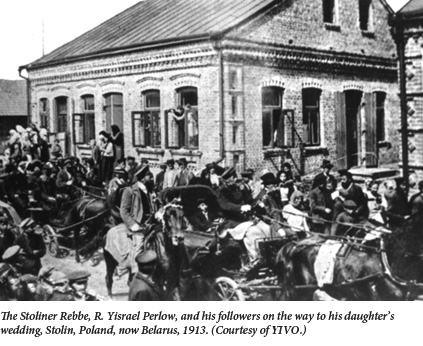

In 1929, while visiting his mother in Pinsk, a young surgeon and aspiring historian of Hasidism named Wolf Zeev Rabinowitsch met the enlightened young Polish tutor of Rabbi Moshe Perlow, the Rebbe of Stolin. The tutor, whose name was David Bachlinski, introduced Rabinowitsch to the Rebbe, as well as to his eldest brother Reb Asher, who had just returned from studying musicology in Berlin. Bachlinski also told Rabinowitsch that the Stoliners had a great collection of historical documents that might be of use in his research if he could be allowed to see them. Rabinowitsch wrote, in great excitement, to the preeminent Jewish historian Simon Dubnow, who encouraged Rabinowitsch to write the history of Karlin-Stolin Hasidism, and even agreed to write a haskama (introductory approbation), if he did so. In the meantime, with Bachlinski and Rabinowitsch’s help, Dubnow published, for the first time, a few of the documents from what came to be known as “the Stoliner Geniza” in his major history of Hasidism the following year. For the next decade, Rabinowitsch (who took a position at a hospital in Berlin in 1931) employed Bachlinski as a research assistant. Their correspondence was central to Rabinowitsch’s scholarly life and he not only preserved it but later wrote a detailed summary of the content.

On July 28, 1929, shortly after Rabinowitsch’s visit to Stolin, Bachlinski reported that the Stoliners had an extraordinary cache of signed letters from several Hasidic and rabbinic luminaries including the Ba’al Shem Tov’s successor, Rabbi Dov Ber (the Maggid) of Mezeritch, Rabbi Levi Yitzhak of Berdichev, Rabbi Yisroel of Ruzhin, Rabbi Avrum Yehoshua Heschel of Apta, the great commentator to the Shulchan Arukh Rabbi Yoel Sirkis, and many others. In addition, Bachlinski claimed that he saw a “Pledge of Allegiance” (Shtar Hitkashrut) by the disciples of the 16th-century kabbalistic master Rabbi Isaac Luria and his leading interpreter Rabbi Chaim Vital, another manuscript in Vital’s handwriting, as well as two large ledgers.

All those things I have read while standing in the cellar where the crate is stored. There were more letters . . . but those had nothing to do with our issue [the history of Karlin-Stolin Hasidism] . . . I wrote down outlines on a piece of paper, and relied on my rather strong memory.

In the fall, Bachlinski reports that the Stoliner Rebbe’s brother-in-law has allowed him to take the two ledgers home to study.

Rabbi Avrum Yakli lent me the two ledgers and allowed me to copy the documents and letters that were in them. I looked carefully at the worn-out sheets ruining my eyes in reading the blurred writing. Many times I had to guess and solve puzzles and riddles, but this time at least I worked in much better conditions. I did not stand in the cellar as the first time, but rather sat at home . . . I snooped and peeked as much as I could, and now you can be rest assured that I have not missed anything of any importance.

In fact, Bachlinski was wrong in thinking that he had seen the whole collection. On the eve of Rosh Hashanah, the following year, he wrote Rabinowitsch:

Three months ago, while still in Stolin, I went down to the cellar accompanied by a granddaughter [of the late Rebbe] and took out several files full of various letters. It turned out that, when I had entered the cellar for the first time the year before, I had seen only a tenth or the twentieth of all the treasure hidden there. I estimate that there are about a thousand letters and other writings of the leading Hasidic figures of all periods (apart from Chabad) . . . If the matter is close to your heart and you are able to interest the relevant people I would advise you to speak with R. Asher and R. Avrum Yakli who are likely to agree-obviously in exchange for some gift-to let this treasure be put into use. In the Geniza I have also found some letters by the Maharal of Prague and R. Chaim Vital whose authenticity must be confirmed by experts. [Emphasis mine.]

Here, and elsewhere, a somewhat contemptuous tone creeps into Bachlinski’s writing. The Stoliner Hasidim, who were far from wealthy, had allowed him to sift through their most precious possessions, including autographed manuscripts of some of the greatest figures of Ashkenazic Jewry going back to the 16th century, without requiring any payment, a task for which Bachlinski himself was being paid. As Rabinowitsch dryly wrote in his notes on the correspondence, the next seven letters, written between 1931 and 1935, contain little Hasidic material “but a lot of material on Bachlinski’s personality.”

In 1935, the first German edition of Rabinowitsch’s book on Lithuanian Hasidism was published and a copy of the book was sent to Bachlinski, who wrote back:

You have appeased me with your important gift, and I have no complaints. I would only ask for one thing. Please make sure to make a few corrections in the Hebrew edition. Do not write . . . “the atheistic youth,” since it will certainly not bring much honor to the Stoliner Hasidim to hear that atheists are singing the melodies of the Great R. Aharon . . . Whatever you wrote in German is not crucial. But if you write like this in Hebrew, it is possible that the book will come into the hands of the Stoliner Rebbe, who will definitely be insulted.

Since Rabinowitsch, who had by now emigrated to Palestine, ended his book with an announcement on “the virtual death” of Karlin-Stolin Hasidism and its rightful inheritance by young Zionist atheists, Bachlinski had a point.

On July 11, 1937, Bachlinski wrote Rabinowitsch with more news of the Stoliner Geniza:

I write to inform you that on June 23 I was released from my teaching at school and was waiting for the money you promised to send me from Eretz Yisrael . . . Since I did not get the money from you I approached Pinsk, and they sent me the first 50 zloty and then another 25 zloty. I traveled to Stolin on the 30th of the same month . . . Reb Asher actually treated me very nicely, but much less so the other people at the court and particularly the son-in-law of the late Rebbe, R. Yisrael-R. Avraham Yaakov Friedman (from the Sadigura dynasty). I was not permitted to do what I wished, and I was not even allowed to read many of the writings, which were said to be family letters, and not intended for the eye of foreigners. However, I was able to copy . . . several items.

Finally and most valuable: a manuscript of Sefer Ha-zoref which has never been printed. This is a large book of Kabbalah with 700 sheets (1400 pages) that was in the house of the Ba’al Shem Tov and had a major influence on the founder of Hasidism. It was written by Yehosua Heschel Zoref of Krakau (born 1633) of whom the Ba’al Shem Tov said, “the messiah’s soul had sparkled in him, and if not for the great kitrug [tragedy] of 1648″ etc. I have copied some parts of the book since it is impossible to copy such a huge book in a short time . . . R. Asher asked me to find a publisher for the book . . . I will send you the material soon, which you should probably bring to that person fond of Hasidism and Kabbalah. I will provide all required details in a letter.

I wished to photocopy the “Pledge of Allegiance” but I was not granted permission, though I offered payment. I just copied with pencil a few signatures. If I succeed in my negotiation regarding the printing of Sefer Ha-zoref, I will be allowed to photocopy this document as well.

The man “fond of Hasidism and Kabbalah” was Gerschom Scholem. Three years later, Scholem published an article on Bachlinski’s discovery of the “Pledge of allegiance of the disciples of the Ari (Rabbi Isaac Luria).” There, he writes, “I have no facsimile of the script itself, but the copier in Stolin copied the signature on a transparent paper following my request from Dr. Rabinowitsch.” Another figure in the background of the story was the publisher and philanthropist Shlomo Zalman Schocken, who supported the research of both Scholem and Rabinowitsch.

Only three days later, Bachlinski wrote a long, excited letter:

I do not have now the mental capacity to write a detailed letter since we are most agitated and enraged by the news regarding the partition of the land [i.e., Palestine]. In my town crowds of Jews surround the post-office daily where one gets the newspapers. All are eager to know whether there are going to be any positive changes regarding the partition. I would like to know what the Yishuv thinks of this edict. I am looking forward to your word and letter, and may we all hear good tidings. And now to the core of the matter.

. . . At the beginning [of my visit to Stolin] I did not find R. Asher at his home, but before the Sabbath I came in and spoke with him about “the holy writings.” He received me nicely, saying that he appreciates me since I am a “man of scholarship,” and my aim is pure science. He did not let me into the cellar that day, but only on Sunday. In the meantime, the situation deteriorated slightly since his mother and her son-in-law, R. Avrum Yakli, listened to the slander of the Hasidim who complained ‘why should we allow a foreigner to see the holy writings?’ But R. Asher stood on my side this time, especially once he heard from me about the finding of the manuscript of Sefer Ha-zoref . . . From a purely historical perspective the book is of little value since it does not at all mention the movement of Shabbtai Zevi though the author lived at this very period. (The book may contain some hints that could be deciphered only by insiders.) . . . On the other hand, the book is an unfailing source for both theoretical and practical Kabbalah . . . Apart from this I have found in it an interesting prophecy about . . . Poland. Please read this passage and be enlightened . . . I am confident that in Eretz Yirsael, the ancient cradle of the Kabbalah, you will surely find someone who would wish to uncover these occult writings.

. . . At the cellar [of the Stoliner Rebbe] I also found the Ba’al Shem Tov’s personal copy of the Zohar (but there are no emendations or notes in the book) and the Alfas that was printed in Venice in 1522 at the printing house of Daniel Bomberg, with handwritten notes by R. Moshe Isserles. The script is very blurred. What should we do with these rare finds? . . . Please let me know your view about all these issues.

As to the money, I have already written to you in the postcard and I am waiting for your order and for good news from our Land in general, and from you in particular. Please send my regards to your housemates and your wife.

Your staunch friend, Bachlinski

On the right margin of the letter’s first page Bachlinski added:

Please contact that Maecenas [Schocken], who might perhaps agree to buy the manuscript of Sefer Ha-zoref from “the court” in order to print it. Obviously, this most honorable man is likely to appreciate this work. I am confident that once you read the introduction, which I have copied, you will surely wish to be among those who enjoy and help the public enjoy its merits.

In the context of his other discoveries, Bachlinski’s fixation with Sefer Ha-zoref is odd. He has, after all, just announced that he has located not only the founder of Hasidism’s personal copy of the Zohar, the canonical work of Jewish mysticism, but the annotated copy of one of the great Talmudic works by the preeminent halakhic authority of the 16th century, Rabbi Moses Isserles, author of the Ashkenazic glosses to the Shulkhan Arukh, as well as several extraordinary letters. These are invaluable documents of Jewish literary and intellectual history that would be treasures in any great library. Heshel Zoref’s unpublished kabbalistic treatise pales in comparison.

But for Bachlinski, part of the attraction of Sefer Ha-zoref was its potential role in undermining the Hasidic self-image. Indeed, his coyness in describing Scholem as “that man fond of Hasidism and Kabbalah” may have derived from the sense that he was betraying those, like Reb Asher, the musicologist brother of the Stoliner Rebbe, who had opened the archive to him, and suggested the printing of Sefer Ha-zoref in the interests of “pure science.”

Rabinowitsch followed up with an obsequious letter written directly to the brother of the Stoliner Rebbe requesting the manuscript of Sefer Ha-zoref:

To the Righteous Rabbi, R. Asher the son of the Righteous Rabbi R. Yisroel, may his memory shelter us, from the descendants of the Tzadikim of Karlin in the Holy Community of Stolin. Peace and all the best!

I hope that His Honor still remembers my visit at his house in Stolin about ten years ago as well as my conversation with His Honor regarding the history of Hasidism in our area, and especially regarding Karlin-Stolin Hasidism.

I have learned from Mr. Bachlinski that in his house there is a manuscript of Sefer Ha-zoref, by the sage and thinker R. Yeshoshua Heshel Zoref, may his memory shelter us, and that His Honor would like to bring the book to daylight and publish it. For why should it be lost in darkness and be, heaven forbid, “like those who have been long dead” [Ps. 143:3]? I hope to find a publisher here, in Eretz Yisrael, a place of Torah and wisdom. Though I heard . . . that Sefer Ha-zoref is voluminous and the printing expenses are high, nevertheless I hope to find a way, with God’s help, to teach and propagate the teaching of the aforementioned sage by the printing of the book . . . With the blessing of the Holy Land, Dr. Zeev Rabinowitsch, who cherishes His High Honor.

Rabinowitsch’s description of the saintly wisdom of Zoref and the religious importance of publishing his manuscript stands in sharp contrast to what he would write less than three years later. In words that Scholem would echo in Major Trends, Rabinowitsch wrote:

Now in the court of the Tzadik in Stolin, there is a long manuscript of a Sabbatean prophet among the holy writings of the Hasidic tzadikim! And the copiers of the book pray that the merit of the Sabbatian author shall shelter them.

In fact, it was Rabinowitsch himself, who, in trying to curry favor with the Stoliner Rebbe, prayed (or at any rate wrote) that Zoref’s “memory shelter us.” The Stoliner Rebbe, however, does not appear to have been impressed. Perhaps he noted the oddness of singling out this particular manuscript out of all of the treasures within his Geniza. At any rate, he did not send Sefer Ha-zoref or any of his other treasures to Palestine.

David Bachlinski seems to have perished a few years later in the great catastrophe of European Jewry. Stolin was conquered by the Soviet army in the autumn of 1939. Although living conditions over the following two years were difficult, as far as we know, the Stoliner Geniza stayed in its place until the German conquest, in summer 1941. According to one witness, a German unit confiscated the collection and loaded it onto a wagon. The Stoliner Rebbe, his family, and community were murdered on the eve of Rosh Hashanah in 1942.

After the war, when Rabinowitsch revised his book, he returned to the melodies of Karlin-Stolin in a more elegiac, perhaps even penitent, mood than when he had written of their adaptation by secular Zionists:

The Karlin melodies still sung here and there in Jerusalem and New York by the surviving Karlin-Stolin Hasidim are the last flickerings of the bright ray of light, which, for six generations, illuminated the darkness of exile for the Karlin Hasidim.

In the very last sentence of the book, he mourned the apparent loss of the Geniza: “Thus were lost important original documents which could have provided valuable source-material for the study of Jewish history.”

However, the Karlin-Stolin community has not flickered out and is once again thriving. There is good reason to believe, moreover, that the collection of literary treasures, which they so carefully preserved for more than a century, still exists somewhere, dispersed or even partially intact. There are members of the community who still scour Judaica libraries and the black and grey markets of Hebraica for further signs of its survival.

Suggested Reading

Something Off

There was a sense of oddness about Bruno Shulz that German-Jewish writer Maxim Biller exploits in his new novella, Inside the Head of Bruno Schulz.

Endless Devotion

Chief Rabbi Sir Jonathan Sacks' new translation of the siddur moves Hillel Halkin to reconsider Jewish prayer.

Searching for Ancient Passover in Samaria and Ethiopia

Bloody bucket brigades and white galoshes: Not everyone celebrates Passover with four cups and four questions. Rachel Scheinerman on Passover in Samaria and Ethiopia.

Why the Kotel Must Be Governed: A Response

Just as soldiers in the IDF have no choice but to eat kosher food, the Jewish state makes decisions as to the nature of its consecrated sites: Jewish decisions.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In