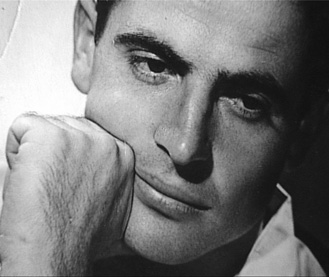

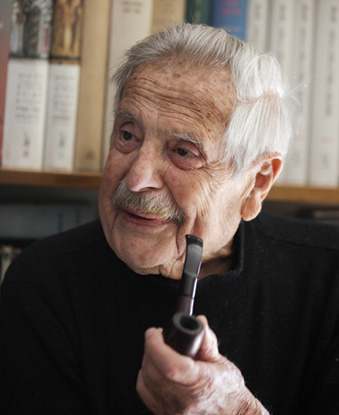

Haim Gouri at 90

Last October I attended a gala celebration of the poet Haim Gouri’s 90th birthday thrown by the city of Tel Aviv. Although Gouri has lived his adult life in Jerusalem, Ron Huldai, the mayor of Tel Aviv, was intent on appropriating this milestone for his city, as Gouri was born in Tel Aviv and, the mayor argued, hadn’t Gouri written innumerable poems about the White City? The large auditorium in the new wing of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art was filled to capacity, and, as a group of actors and musicians alternately declaimed Gouri’s poems and played musical settings of them, the audience sat in rapt attention, at home with dozens of texts for which only the titles were given in the program. Finally, the poet himself was helped to the stage. Although Gouri was a little unsteady on his feet, his voice was confident as he honored his hosts, evoking the heady days of Tel Aviv’s literary cafes and reciting stanzas of its great poets from memory.

The Israeli literary supplements last fall were full of long interviews with Gouri conducted by such well-known writers as Meir Shalev, Ariel Hirschfeld, and Nir Baram. Over the holidays last fall, the great critic-scholar Dan Miron published a seven-part series on the inner development of Gouri’s poetry in Ha’aretz. The Bialik Institute together with Kibbutz Ha-me’uchad put out two large volumes of Gouri’s prose.

It’s hard to exaggerate the importance of poetry in 20th-century Israeli culture. The willful disengagement from Orthodox beliefs and practices that accompanied the Zionist revolution left the spiritual needs of secular Israelis unattended to, and the writing and reading of poetry have often become a kind of sacrament filling that void. Beginning in Eastern Europe and continuing in Palestine, Hebrew readers looked to poets not only to illuminate their private experience but also to serve as secular prophets.

Each generation of the Hebrew literary public has further sought to invest some figure with the real if unofficial status of “national poet.” It began with Bialik and was passed on to Natan Alterman. For some, the awesome Revisionist poet Uri Zvi Greenberg bore the mantel. Later in the century, that distinction belonged to Yehuda Amichai. But Amichai, who is very different from his contemporary Gouri as a poet and a public figure, died in 2000. Since then, Gouri has taken the position, and there are many who would say that it has been his all along. The only other living contender is Natan Zach, age 83, whose brilliant, stripped-down existentialist verse revolutionized Hebrew poetry in the 1960s. But Zach doesn’t fill the bill for two reasons. To be a national poet, it hardly bears saying, one has to evince sympathy for the nation, and Zach has long distanced himself from the Zionist enterprise. Moreover Zach never followed his stylistic breakthroughs of 50 years ago with accomplishments that connected with the poetry-reading public.

Here is where Gouri has shone. Rather than marching in place or remaining content to recycle his favorite themes, at the age of 86 in 2009 Gouri published a book-length cycle of poems called Eyval—more on the meaning of the title and the significance of the work later on—that was regarded by readers and critics alike as perhaps the best thing he had ever written. Gouri thus spared the public the embarrassment of having to celebrate him at 90 as a literary relic—the kind of grand old man of letters whose only recent achievement is his longevity. Instead, the new late-in-life book stimulated public discussion about the shape of Gouri’s career and how it moved from its initiation in the War of Independence through several discernable stations to arrive at this late consummation.

That Haim Gouri is not well known to us in America is regrettable but hardly surprising. Here the contrast with Amichai is instructive. Amichai served in the British army in World War II, admired and was influenced by Auden, and made his living by teaching American Jews studying in Jerusalem. He was a popular visitor on American campuses and, because he knew English well, was able to supervise closely the translations of his poems, most of which appeared on these shores. Gouri, on the other hand, was oriented toward Europe, to the degree to which he looked beyond Palestine/Israel at all. He spent a year at the Sorbonne after his studies at The Hebrew University and remains more comfortable with French culture than with English or American. The only book-length sampling of his poetry in English is a bilingual selection translated by the late Stanley F. Chyet, Words in My Lovesick Blood: Poems by Haim Gouri.

Interestingly, there is one hidden point of connection between Gouri’s poetry and American Jewish culture. Anyone who attended Jewish summer camps or participated in Zionist youth movements in their heyday probably remembers singing the haunting Hebrew song “Bab El Wad” around the campfire. The lyrics are by Gouri and the melody by Shmuel Farshko. The title (literally, the gate to the wadi; Sha’ar Hagai in Hebrew) refers to a narrow corridor 23 kilometers from Jerusalem on the road from Tel Aviv. In 1948, during the siege of Jerusalem, the only way to get supplies to the city was to push makeshift armored vehicles through the blockade. Many Jewish soldiers lost their lives in the effort, and the burnt-out shells of these vehicles, which have been maintained as a memorial, can still be seen on the drive between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. (Many versions of “Bab El Wad” can be found on YouTube; I recommend one by Shlomo Gronich because of the contemporary photographs that accompany the words.) This is one of a number of song lyrics that Gouri wrote in the eye of the storm in ’48 that became instant classics by brilliantly realizing the mood and spirit of the Yishuv in the midst of the struggle and its immediate aftermath. Here is the chorus and one of the stanzas from “Bab El Wad.”

Bab El Wad, forever remember our names!

Convoys broke through on the way to the city.

By the side of the road lay our dead.

The iron skeleton is silent like my comrade.

And I walk, passing here in utter silence.

I remember them, each and every one.

Here we fought on cliffs and boulders,

Here we were one family.

The atmosphere of sacrifice lies heavy upon these lines. The dead are freshly dead, laid out awaiting transport for burial. The comparison of their silence to the burnt-out shells of the armored vehicles expresses outrage and grief. Yet the horror is mitigated by the supremely meaningful nature of the deaths and by the fact that they were not, and will not be, alone. Not only did they fall defending their brethren in a desperate war of survival, but their efforts succeeded. The blockade was breached and Jerusalem resupplied. The soldier who survives, the “I” who walks in silence, justifies his own survival by a vow to remember the name of every fallen comrade because they were not merely comrades-in-arms but members of one family.

Split from their music, such lyrics can seem stilted and over-laden with emotion, but they make sense when they are sung, and in the decades that followed they were sung very often indeed, performing the function of a communal rite of remembrance on the part of the surviving, belated members of the national “family.” Gouri himself

regarded them as lyrics rather than poetry and did not include them in his collected verse. But the iconic status of these early songs had a paradoxical effect on his career. It gave him recognition far beyond the circles of readers of serious poetry, but at the same time it associated him indissolubly with the moment of 1948 and the high pathos of struggle and sacrifice attached to it.

Gouri’s first published book of verse, Pirchei eish (Fire Flowers, 1949), did not do much to shift the perception of Gouri as a war poet. To be sure, these were highly accomplished poems in their own right, not song lyrics. Yet, within this higher literary register, they performed a similar elegiac function and projected the feelings of tragic renunciation felt by a generation called by destiny to give up the normal prerogatives of youth—first love, studies, travel—and afterward felt unworthy when measured against those who had made the ultimate sacrifice. Although the voice in these poems was Gouri’s own, the style of the poetry owed a great deal to Natan Alterman, the great eminence in Hebrew literary circles in the 1940s and 1950s. The lush figurative language and the neo-symbolic pathos Gouri borrowed from the master were oddly fitted to the experiences of violence and sudden loss on the battlefield. Within a few years, when Amichai and Zach began to turn the poetics of Hebrew verse upside down, Gouri’s debut came to seem more like an homage than a new departure.

To understand Gouri’s literary growth it’s useful to know something of his origins. He was born in Tel Aviv in 1923 to parents who had emigrated from Russia. Committed Zionists, they came to Palestine already speaking perfect Hebrew and spoke no other language in the home, not even when they wanted to keep secrets from their children. The atmosphere of the home was utterly secular: no Shabbos candles, holidays, or bar mitzvah. Gouri recalls his mother saying that for the human heart there are no fixed observances.

His schooling reinforced Zionist socialist values. General subjects were studied, along with Bible and Hebrew literature, but there was little about the millennia of Jewish life in Europe. The past in general, except for periods of ancient biblical glory, was deemed irrelevant. It was all about the promise of tomorrow. The walls of the clubhouse of the Makhanot Ha’olim youth movement, to which Gouri belonged, were festooned with placards carrying such slogans as: “You are the rock upon which the sanctuary of the future will be built.” The violence surrounding the Arab revolt of 1936−1939 was a formative experience during his adolescent years. After two years on a kibbutz, Gouri attended the elite Kadourie Agricultural School in the Lower Galilee, where Yitzhak Rabin and Yigal Allon were classmates, before joining the Palmach. He participated in paramilitary actions aimed at hastening the British withdrawal from Palestine. In 1947 he was sent to Hungary and Czechoslovakia to organize the illegal aliyah of the remnants of Zionist youth movements. In the War of Independence he served as a deputy company commander on the southern front. After the war, he studied at The Hebrew University and the Sorbonne before undertaking a career as a journalist for labor and left-wing newspapers.

Gouri was a member of the first truly native generation, born in Palestine, raised wholly in Hebrew, and formed in the crucible of the struggle for statehood. This is, to be sure, the heroic stuff of modern Jewish history, but it is also a formation that entailed significant blind spots. Blacked out is the life of the Jewish people in the diaspora, not just the shtetls of Eastern Europe, but the vast, adaptive civilization of the Jews from the Babylonia of the Talmud to the golden age of Andalusia and Maimonides and then to the rabbinic and mercantile elites of Ashkenaz and Poland. Early on, Gouri began to come to terms with these limitations. The year he spent in Central Europe after the Holocaust was an education, exposing him not only to the enormity of what had taken place but also to the human faces behind it. His studies in Jerusalem helped him fill in the not-inconsiderable cultural space between the Bible and Bialik. As it happens, it was through Bialik and Rawnitzki’s great anthology of rabbinic legends Sefer ha-agada that Gouri encountered the spiritual world of the Talmud. He also read the great medieval Hebrew poets and delved into the High Holiday machzor. Gouri is the kind of poet who makes room for new influences rather than divesting himself of old commitments. The discovery of diaspora Jews and their culture surely affected his sabra attitudes, but rather than renouncing that core identity he simply became a larger poet.

The attention given the Holocaust in Gouri’s work makes him unique among the native writers of his generation. As harsh as it is to say, Zionist ideology had made the destruction of European Jewry into the chronicle of a death foretold. No one had foreseen the specific mechanisms of its execution or its national source—that it came from the enlightened West rather than from the Slavic East was a surprise—but the disappearance of Europe’s Jews through pogrom or assimilation had been considered inevitable. This certainty derived from a scathing critique of the physical passivity and moral corruption of diaspora Jews. When the predictions became fact, the catastrophe engendered a deep sense of shame and confusion in those who had been raised in the youth movements of the Yishuv. What stance could be taken by young people who were preparing for the defense of their land and people toward their brethren who, as it was commonly thought at the time, had passively submitted themselves to death?

This may be familiar territory, but it’s worth recalling in order to gauge the singularity of Gouri’s response. The year Gouri spent in Europe after the war working with survivors when he was 24 was the beginning of a long process that reached its climax when he covered the Eichmann trial in 1961 for La-merchav, the newspaper of the Labor-left Achdut Ha-avoda party. His dispatches are fascinating documents because of the tension they record between the trial testimony, which he dutifully describes, and his subjective responses as a native Israeli. Early in the trial, for example, a witness named Morris Fleischman related how, as an act of public humiliation, he and the chief rabbi of Vienna were ordered to go down on their hands and knees and scrub the sidewalks, and how the rabbi, dressed in his tallit, endured this as an act of God. Gouri’s immediate response is disgust: “I had no desire to listen to this broken, decrepit man go on and on about his afflictions. . . . I would prefer attending the Nachal (the army pioneer corps) ceremonies taking place today at the stadium and seeing strong young people.” And yet, he writes, “Morris Fleischman’s testimony grabs me by the throat with incredible force and says to me: ‘Sit down and listen to every word!’” Gouri’s honesty is bracing, and it allows those of us who are often caught up in our own righteous hindsight to understand just how difficult this moral readjustment must have been for Israelis.

Gouri persevered in his engagement with the Holocaust. Stepping out of his métier as a poet, he published in 1965 a stunning short novel called The Chocolate Deal, which stages an encounter between Ruby and Mordy, two survivors in an unnamed

German city several months after the war’s end. Ruby is all activity and mobility unburdened by shame and self-reflexive memory; he is busy with schemes for cornering the market on surplus Allied chocolate. Mordy is flooded by memories of suffering, not only his own but those of others who sought to hide him. Gouri stretched himself in another direction when he was asked in 1974 by the members of Lochamei Ha-geta’ot (The Ghetto Fighters) to prepare a documentary film for the kibbutz’s Holocaust museum. Despite having no experience in filmmaking, Gouri worked over the next 13 years to produce a trilogy of well-regarded films: The 81st Blow, The Last Sea, and Flames in the Ashes.

This is how Gouri ends a poem (“Inheritance,” translated by Stanley Chyet) written in the 1950s about the Akeidah, Abraham’s almost-sacrifice of his son:

Isaac, we’re told, was not offered up in sacrifice.

He lived long,

enjoyed his life, until the light of his eyes grew dim.

But he bequeathed that hour to his progeny.

They are born

with a knife in their heart.

Although the Holocaust is not explicitly mentioned, it doesn’t need to be. Already at the end of the 11th century, survivors of the crusader massacres called attention to the somber fact that, compared to Abraham’s uncompleted act, the sacrifice of their martyrs had been fully consummated. So too in Gouri’s retelling of the Akeida. Even though the angel intervenes and the knife drops from Abraham’s hand and Isaac goes on to live a long and happy life, the intended wound takes on a life of its own. Like a Jewish version of original sin, each new generation is born with a sense of dread. For a member of the heroic cadres that fought for the establishment of Israel, this is no small admission. It is one of the things that makes Gouri a great poet.

The poetic “I” that speaks in most of his poems, though firmly planted in its home ground, is open to contemplating antagonistic arguments and points of view. But this is hardly a simple liberality of spirit or a Whitmanesque embrace of a world of contradictions, as indicated by the title of another poem from the 1950s, “Civil War,” translated here by Stanley Chyet:

I’m a civil war

and half of me fires to the last

at the walls of the vanquished.

I’m a court martial

working in shifts,

its light never dimmed.

And those in the right fire on the others in the right.

And then it’s quiet

a calm composed of fatigue and darkness and empty shells.

I’m nighttime in a city open

to everyone who’s hungry.

In the temporary calm that comes from exhaustion rather than resolution, the speaker compares himself to an open city using allusions that pull in two directions. The last two lines allude to Roberto Rossellini’s 1945 film Open City, about war-torn Rome as a defenseless space open to looting. Yet Gouri closes the poem in a surprising note of generosity with the familiar Aramaic phrase from the Passover haggadah that offers the “bread of affliction” to all who are hungry.

This poetic conceit became very real at an important juncture in Gouri’s career. After the Six-Day War, Gouri signed a manifesto supporting the Movement for a Greater Israel, a circle of secular writers and intellectuals—these were not the messianists of Gush Emunim—who advocated incorporating Judah and Samaria into the state of Israel. Gouri’s participation was solicited by Natan Alterman, who overcame the younger poet’s hesitations by laying out a vision of a single state with a Jewish majority—achieved by mass aliyah from the West—in which the Arabs would form a respected minority with full religious and national rights. Gouri was not a man of the right, but he had been formed by a Zionist youth culture that imbued him with a deep connection to the Land of Israel in its totality (all parts of which were accessible when he was growing up) and esteemed the value of hulutsiyut, pioneering and self-realization through settlement on the land.

In 1975, thousands of supporters of Gush Emunim occupied the old Turkish train station at Sebastia, deep in the Shomron. Until that point, the IDF had been removing settlers as soon as they established themselves, but this demonstration was bigger, and it took place against the background of Arafat’s defiant, gun-in-holster appearance at the United Nations and the resolution condemning Zionism as racism. Gouri had been reporting on this tense confrontation between the settlers and the army when he was prevailed upon by the settlers to serve as a go-between between them and the Rabin government. He brokered a deal that allowed 30 persons—later interpreted as 30 families—to remain at Sebastia legally, the first in a series of concessions made by the Labor government that allowed settlements to spring up.

In time Gouri came to regret this as one of the greatest mistakes in his life. He had crossed the line between objective journalist and active participant. More disturbing were the violent excesses of the settler movement in the years to come. Nor did Gouri foresee the heavy moral price paid by Israel, especially by young soldiers as they policed Arab population centers, in ruling another people.

Yet rather than blaming the extremists, Gouri turns the light of moral scrutiny upon himself and his generation. It is this kind of grand self-reckoning, a heshbon ha-nefesh, that is the burden of Eyval, a cycle of 86 poems that has been widely celebrated as the late fruit of Gouri’s career. The title comes from the covenant ceremony in Deuteronomy 27, in which Moses delivers the blessings concerning Israel’s future on Mount Grizim and the curses on Mount Eyval. The place name conveys the somber mood of the composition. Gouri looks back and finds his generation—his comrades from the Palmach and the youth movements who forged the institutions of the new state—responsible for a fundamental error. In the heat of their bravery and in their heartfelt identification with the Land of Israel, they were blind to the trauma and disenfranchisement Palestinian Arabs had undergone and to the consequences their ordeal would eventually bear. Gouri sees no guile or malevolence here; the error was an unintended—but not necessarily unforeseeable—result of the legitimate goal of creating a Jewish homeland.

Gouri is no post-Zionist. Israel’s enemies and their evil intentions are real. There are no fantasies of undoing history, and no rosy visions of resolution. All we can do, says the speaker of Eyval, is to open our eyes, renounce self-congratulation, become aware of the chances we missed, inhabit our regret with courage, and await judgment. What saves this reckoning from prophetic righteousness is Gouri’s refusal to stand apart from his peers. The “we” that prevails in the poems is not moral camouflage but a generational collective for which Gouri takes full responsibility. In Pirchei eish (Fire Flowers), his debut collection in 1949, he had spoken in the first-person plural and afterward spent decades on his own poetic subjectivity, apart from the collective. In Eyval, 60 years later, Gouri returns to “we,” but on terms that are noticeably different.

Any summary of the political argument of Eyval is destined to sound crude, not because it simplifies the nuances of analysis but because it is beside the point. What is most real is the experience of regret, not its source. The poems explore what it’s like to abide the uncertainty that is created when the principles that have guided one’s life have been severely questioned. After admitting that “Almost all the holy cows have been slaughtered,” the poet confesses:

It’s difficult for me personally without those cows.

For years and years I pastured them.

I am coming to resemble Methuselah,

Another holy cow that has been slaughtered.

A great and much celebrated poet, a national institution, Gouri could have cruised into the last, late phase of his career. There is something breathtaking in his choice to knock his halo askew and forfeit the pose of the vindicated prophet.

Eyval demonstrates how great, luminous poetry can be made out of remorse. Gouri’s persona in the poems manages the neat trick of accepting responsibility for his past actions and at the same time not taking himself too seriously. A gift for self-irony and wit leavens the gloom. There are antic shifts between wildly disparate registers of Hebrew; a rare biblical term will share a line with a conversational catch phrase or a piece of army lingo. For a poet so schooled in secularity, there is also an unexpected reaching out to the language of Jewish prayer. The experience of awaiting judgment is the fundamental mood of Eyval. The desire to know who will withstand this scrutiny is expressed by the question “Kama ya’avrun?” (How many will pass?); the echo of the U’netaneh Tokef prayer of Yom Kippur is unmistakable. References abound to the Ne’ilah service that brings the holiest of days to its conclusion. Here, at the end of Gouri’s long career, he ranges over the entire Hebrew and Jewish tradition to create a poetry of wisdom.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Drowning in the Red Sea

Gennady Estraikh said, "It is hardly an overstatement to define Yiddish literature of the 1920s as the most pro-Soviet literature in the world." When Arab riots killed 400 Jews in Palestine in late August 1929, the Yiddish communist press found itself torn between sympathy for the fallen and loyalty to the Revolution.

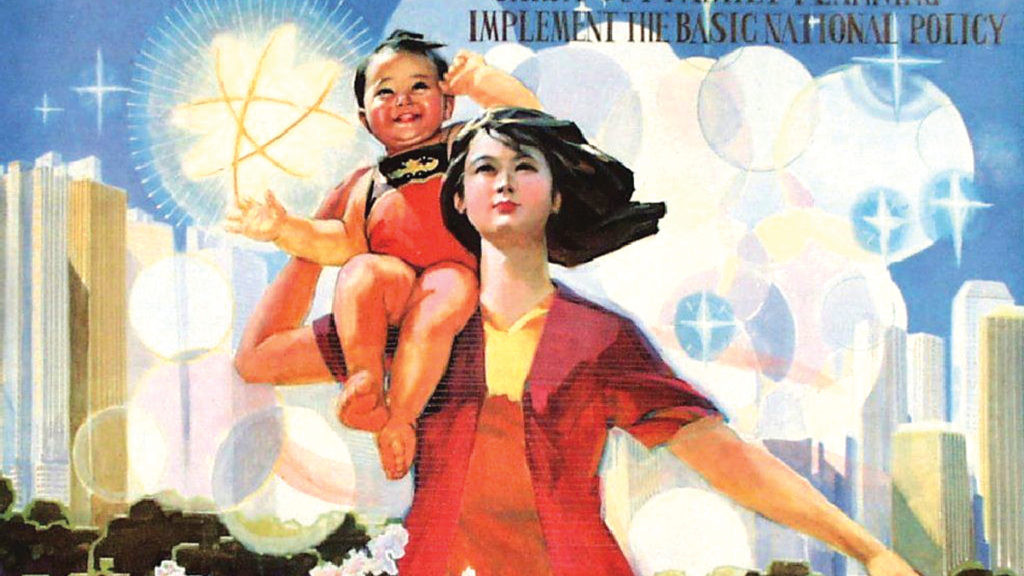

On Not Bringing Up Baby

What happens when the rising cost of raising children meets the downward pressure on reproduction?

“The One You Love”? A Case of Divine Disappointment

Which son did Abraham favor? Reading "the binding of Isaac" with fresh eyes.

Where To: America or Palestine? Simon Dubnov’s Memoir of Emigration Debates in Tsarist Russia

Dubnov's magisterial autobiography, written while Dubnov was in exile from both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, takes the reader on a deeply personal journey through nearly a century of upheaval for the Jews of Eastern Europe. A new translation.

gwhepner

JEWISH SPOUSES ARE THE ANTIDOTE TO WHAT ISAAC BEQUEATHED

Isaac bequeathed, suggested Haim Gouri,

to every Jewish heart his father’s knife,

for which he is acquitted by this jury,

the antidote to knives a Jewish wife,

or, in the case of Jewish wives, a Jewish

husband. According to the law of Moses,

provided that their conduct is not shrewish,

both blunt the Ikey knife with symbiosis.

[email protected]

gwhepner

HOW MANY OF US AFTER NEW YEAR’S DAY WILL PASS?

“Kama ya’avrun?”

“How many of us after New Year’s day

will pass, how many of us pass away?”

the cantors love to croon.

Despite how much we pray,

we’ll learn of those who failed pass, and lost,

compelled to pay Death’s Angel death, the cost

of life we all must pay.

[email protected]