Yo’s Blues

Midway through Life on Sandpaper, the fictional memoir of Israeli writer Yoram Kaniuk’s time in 1950s bohemian New York, after nearly two hundred pages of befriending (and sometimes bedding) famous musicians, painters, actors, and directors, Kaniuk admits that he didn’t fit in. “I was in the lives of these people by mistake . . . I was passing through.” It’s a strange admission for an artist so clearly on the make, someone endorsed by Meyer Schapiro, someone who appeared destined for fame or, at the very least, a post-obscurity revival of interest. But we hear another version of this pronouncement at the end of the book when Kaniuk is told by a close friend, “For you New York could have been a new homeland, but you missed out on it.” While the sentiment is the same, there’s a noticeable difference. To “miss out” indicates that there was the possibility of belonging, even as the memoir persistently suggests that he could never find another homeland.

Life on Sandpaper is a good, if very uneven, book that will enthrall at least some readers with its amazing sense of motion while leaving others frustrated by the lack of a plot, incomplete character development, and dubious veracity. For most of the book, Kaniuk is less the hero of his autobiography than he is a vehicle for painting or performing American culture in the 1950s, often leaving New York for the wilds of the West. This is On the Road as re-imagined by an Israeli, filled with chance encounters and memorable adventures that attempt to capture bohemian life in mid-century America.

The son of the first curator of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Kaniuk arrived in New York as an aspiring painter shortly after fighting in the 1948 War of Independence. He is drawn by the excitement of the city, by jazz, Beat poetry, and new kinds of painting. The dream of New York is a chance to transcend racial or ethnic origins through art, and there are moments when it looks like he’ll succeed. Billie Holiday renames him “Yo,” and writes a song called “Yo’s Blues” in his honor. Later he is invited to paint his friend Charlie “Bird” Parker, the only painting, we’re told, for which Parker ever sat. Marlon Brando sleeps under a portrait of Kaniuk’s mother, while James Dean spends hours in the studio just watching Kaniuk paint. In Kaniuk’s America, the drunk next to you at the lunch counter is liable to be James Agee, rambling semi-coherently about American decline. Most remarkably, all these luminaries accept Kaniuk. Even Agee, who refuses to look at Kaniuk’s paintings because he is an Israeli colonialist, gives him a rare copy of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. If this all seems a bit fantastic, it probably is. The poet Hayden Carruth already publicly doubted some of Kaniuk’s reminiscences years ago, describing the “absurdity” of one of his emotionally charged anecdotes.

Yet these unbelievable encounters with famous people are more than just great stories. (Though they are often emphatically that.) The use of real people helps to anchor Kaniuk’s lively prose. Here he is describing Holiday:

The sad humor of the musicians. Billie Holiday reached for notes and sang them as if she were weaving a sad carpet and she’d take me on walks and I talked and she listened or maybe she didn’t, and said she didn’t understand that crap. We kissed. She said she’d had better kissers. I was there and she wanted to kiss somebody and I was nearest and I was talking and making a fool of myself.

We are in Minton’s Playhouse, the legendary Harlem nightclub, when this reminiscence begins, but we end somewhere else, somewhere less material and more impressionistic.

Kaniuk writes that at the time he was learning how to “paint jazz, think jazz, breathe jazz,” experimenting with ways to transfer its kinetic energy and rhythm into a static form, and this book would appear to be the literary extension of that project. The brief mention of “Billie Holiday” lets Kaniuk emotionally wander and modulate without having to worry about character development; we know who Billie Holiday is, and carry everything we know about her into the scene, which Kaniuk can then enrich through digressions and detailed descriptions of peripheral actions. Perhaps it doesn’t matter whether or not the events Kaniuk describes took place. The style gives us an image of 1950s America with an intensity that traditional realism—or traditional memoir—probably could not.

Though Life on Sandpaper is a memoir (or novel) of discovering America, Kaniuk can never transcend his national and ethnic origins. He was shot fighting for the Palmach in the War of Independence, and the wound makes it impossible for him to stop being an Israeli partisan. People either fall over themselves to do him favors because he is Israeli or they burst out into anti-Semitic tirades. In Las Vegas, Kaniuk and his friends are welcomed as heroes by Jewish gangsters. They give them food, drinks, even medals, in honor of their service for Israel. They sing Hebrew songs and invite them to their weddings. When Kaniuk and his friends win too much money, the Vegas Jews again show kindness to them by asking them politely to leave Nevada. For a few pages, he’s a friend of Miles Davis, but Miles grows jealous of Kaniuk’s friendship with Bird and seeks to undermine him by publicly launching into anti-Semitic diatribes.

As much as Kaniuk tries to see the world as a free Beat, he still has the mindset of a 1950s Zionist. This comes out most clearly in his description of New York’s Jewish literary scene. Kaniuk takes a job as a go-between for rival groups of Yiddish and Hebrew authors at a cafeteria on the Lower East Side. The Hebrew authors despise Kaniuk and the Israelis for their corrupt Sephardic pronunciations, while the Yiddish writers are fighting their tragic losing battle. The two camps refuse to talk to one another, except at funerals, where they lovingly embrace over fallen friends. A woman in black sits at the entrance to the Forward, crossing off the names of the recently deceased from her subscription lists. This is a version of an old joke, reverently told by Cynthia Ozick in her story “Envy,” that reads bitterly here. If you aren’t an international bohemian like Norman Mailer (who sells Kaniuk a puppy), or an Israeli like Kaniuk, then you are a dying diaspora Jew, an ideological abstraction.

What makes this depiction of New York Jewish culture in Life on Sandpaper so frustrating is the actual vibrancy of Jewish literary life at the time. Isaac Bashevis Singer, improbably one of the Yiddish writers at Kaniuk’s cafeteria, is just coming to mass attention, and is writing some of his most interesting stories and novels. This is the heyday of Partisan Review and the early years of Commentary, and Saul Bellow and Isaac Rosenfeld live only blocks away from Kaniuk and his circle. Kaniuk knows that this world exists; he mentions Clement Greenberg but only to deride his taste in art. Kaniuk apparently had no interest in participating in, or presenting, a living American Jewish culture. Readers interested in a more Jewish bohemia must turn elsewhere, to Wallace Markfield’s novel To An Early Grave, or to Steven Zipperstein’s recent biography of Rosenfeld, Rosenfeld’s Lives.

The moment in his story when Kaniuk can no longer be an international bohemian comes when, almost without warning, he abandons painting for writing. Painting, like jazz or dance, is a non-verbal medium, universally accessible. As long as he is a painter, he can be accepted by an international community, but literature forces Kaniuk back into Hebrew and into a fixed national identity. He stops being “Yo” and becomes Yoram K, the latest iteration of the Jew struggling to find his place in modernity. Mid-century icons still appear for their star-turn cameos in the second half of the book, but less frequently, and his circle of friends narrows until it is all—but exclusively Israeli. Kaniuk may have moved to America, but the Israeli artist only succeeded in creating a second exile. He has no choice but to return.

The story of Life on Sandpaper is that Kaniuk came to America to make it as a painter, only to realize that his true artistic self was in another language and country. He didn’t “miss out” because he really was just “passing through.” But the fun (and beauty) of the book is not in the narrative; it is in its style and vivid anecdotes. The second half of the memoir, after Kaniuk abandons painting and discovers he can’t escape his Israeli identity, is significantly more coherent than the first. But the parts that will stay with you are the fragments, the momentary flashes of brilliance when Kaniuk evokes the rush of a night on the town with Bird and Lady Day.

Suggested Reading

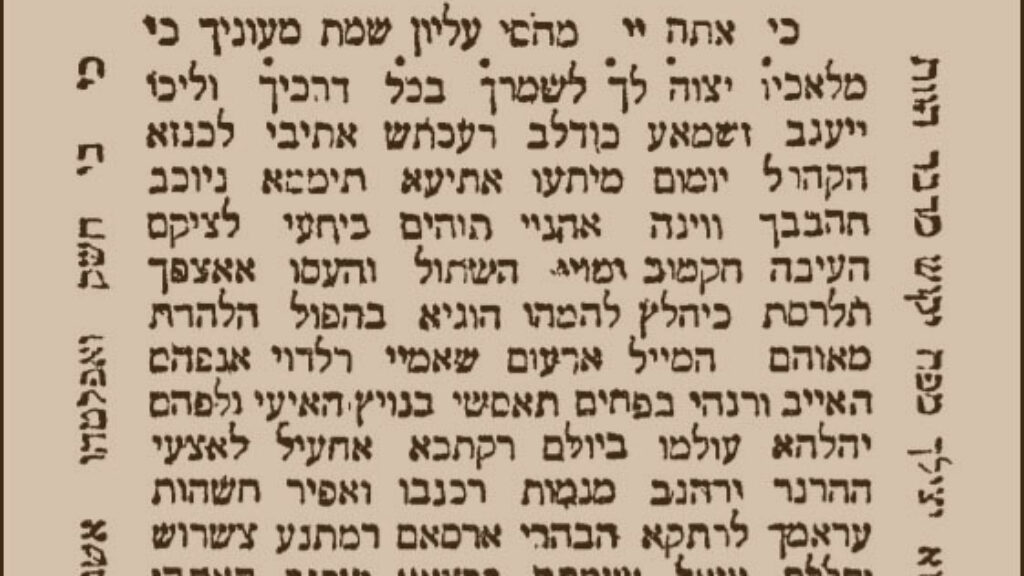

Rov in a Time of Cholera

From limiting minyan sizes to magical amulets, a look at how one rabbi faced waves of cholera epidemics over his long 19th-century career.

Indiana Jones and the Meme-ification of Nazis

What happens when pop culture becomes responsible for maintaining historical memory? Benjamin Weiner has a bad feeling about it.

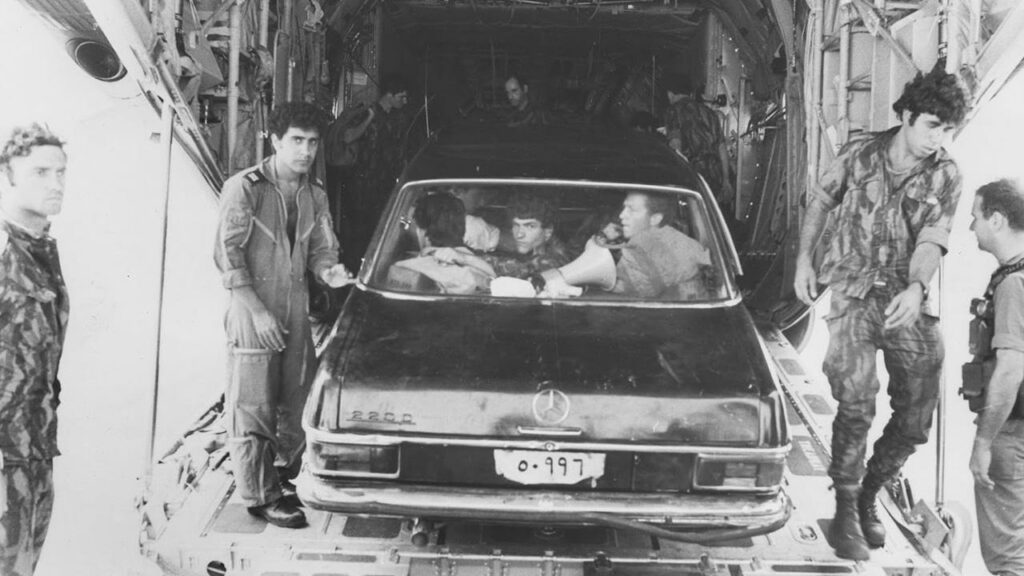

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef and the Halakhot of Hostages: Part II

When Israeli citizens were taken hostage in Entebbe in 1976, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef was asked if hostages could be exchanged for terrorists. What can his towering responsum teach us about the current moment?

Montefiore and the Politics of Emancipation

More than a shtadlan.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In