Heaven from Torah: An Interview with Shai Held

In the most recent issue of the Jewish Review of Books, Ilana Kurshan offered a thoughtful review of Shai Held’s new two-volume work, The Heart of Torah, a series of essays on the weekly Torah portion. I sat down with Shai to ask a few questions about his experience writing the book, the subtle ways it has begun a dialogue with some Christian communities, and his thoughts on the future of American Judaism.

Your book offers on average two essays on each of the weekly Torah portions, written originally as stand-alone weekly divrei torah (sermons) and then collected together. What did you learn in the process of writing and revising these essays?

I was most struck by how many biblical narratives became ever more open-ended and elusive the more carefully I studied them. For example, I was just talking with my eight-year-old son about the story of Moses hitting the rock in Parshat Hukkat, the behavior that leads God to say that he cannot enter the Promised Land, and why it is so hard to figure out exactly what Moses did wrong. I think it was the 19th-century scholar and exegete Samuel David Luzzatto who kind of wryly observed that the commentators basically keep loading more and more sins on Moses—even inventing them—because they cannot figure out what he had done to make God so angry. I’m not sure I fully grasped that—how much the Torah really wants us to ask all kinds of questions—until I was almost done writing the book.

What do you hope readers will take from these essays?

I spent many years of my life preoccupied with different Jewish approaches to the question of what Torah min ha-shamayim (Torah from heaven) means. And then in one of Abraham Joshua Heschel’s great turns of phrase, he really altered that for me when he wrote that the primary question is less Torah min ha-shamayim (Torah from heaven) than shamayim min Ha-torah (heaven from Torah). It’s how the Torah can be a site for encountering God, for feeling called, compelled, commanded to live in a certain way, to do certain things, to feel in certain ways. In some ways, my deepest aspiration for this book is that readers will have moments of experiencing shamayim (heaven) in reading it. That’s not because of any great power of mine; that’s because I actually have faith in the power of this text and the tradition of commenting on it—these are just endlessly rich and powerful. And I don’t have a philosophical argument for that; I just have abundant experience of it.

Among the 101 essays in your book, what themes recur frequently?

I didn’t start out with an agenda, but of course certain themes rose to the fore: the notion of a God of love, the notion of a God who demands a just society, people taking responsibility for both their actions and their character, and the role of covenant in Jewish theology.

You don’t read like an academic biblicist (like your late father Moshe Held), nor like a typical rabbi. Your readings are very philosophical and theological. For example, this week’s Torah portion, Va’etchannan, contains the oft-repeated prohibition against making idols. Most later commentators assume, in your words, that “the problem with images is that they compromise God’s otherness and transcendence.” But you point out that here the Torah takes an opposite view: For what great nation is there that has a god so close at hand as is the Lord our God whenever we call upon Him? (Deut. 4:7) The problem with idolatry, you argue, is not that it somehow impinges on God’s transcendence. Contrariwise, God is so close, so imminent, that Israel has no need of idols to feel God’s presence. What originally drew you to this way of reading Torah?

From the time I was a little kid, I was preoccupied with theological questions. I remember as a little boy, I think I must have been in second grade, saying to my father, “My teachers in yeshiva say that Moshe wrote the whole Torah but I know you don’t think that—so how should I think about it?” Those kinds of questions were just really basic to me.

Does your father’s work on the Bible figure in here?

It’s interesting that you ask that. From the time my father passed away when I was 12 years old until my mid-30s, the Bible was the very last Jewish book I was interested in because I needed, I don’t know, space to become my own person—I just needed to stay away. It really wasn’t until much later in my life—my late 30s—that I started studying Tanakh in a serious way.

My father was an influence in that I really learned from him what it means to be utterly dedicated with every fiber of your being to a close reading of a text. Yet the lenses that I bring, the questions that I ask are so different from his. My father was a philologist, not a philosopher in any way; it wasn’t the language he spoke or even really related to. It has struck me that in many ways my father and I loved many of the same texts with our whole hearts, but we loved them in very different ways.

This week’s Torah portion, Va’etchannan, contains the Deuteronomic version of the Ten Commandments. In your essay, you offer an explanation for the last one: You shall not covet . . . Here, you ask whether coveting is an internal state—an intense longing—or an external action—taking. One of the earliest rabbinic commentaries, the Mekhilta, thought the prohibition was on physically taking something, which leaves open the question of how coveting differs from theft. Ibn Ezra thought that the prohibition is on feeling intense desire for something that one cannot have. Maimonides argued that the prohibition is really against coercive purchase. You point out, with some help from Old Testament scholars Brevard Childs and Marvin Chaney, that other examples of coveting in Tanakh point to the idea that the prohibition concerns officials abusing their power to take from others: David taking Uriel’s wife Bathsheba, King Ahab taking Naboth’s vineyard. So you read it as a commandment against the abuse of power.

How did you find your way to some of those commentators who might be less likely—for instance, the more obscure Christian scholars?

Many Jewish scholars are focused on textual, grammatical questions. Christian Bible scholars tend to be more focused on theological readings. I found myself often reading very devoutly Christian readers because they were asking the kinds of questions that I wanted to ask, so they became my natural conversation partners and teachers. Now, obviously, there were moments and times where their readings were so heavily Christian that I resisted or didn’t feel compelled by their readings, but there was still an awful lot that I learned from that.

Let’s talk for a minute, if you don’t mind, about Hadar. Hadar is an institution you helped found and continue to lead, whose stated mission is to empower Jews to create and sustain vibrant, practicing, egalitarian communities of Torah, Avodah, and chesed. Hadar is observant and egalitarian, which makes it appear to be closely aligned with the Conservative movement. Why does it not identify with that movement?

I actually find myself baffled by that question. The students who come and study full-time at Hadar more often identify as Orthodox than as Conservative. And our mode of learning and the culture of our beit midrash are very different than what you find in the Conservative movement. I have great respect and indebtedness to the Conservative movement, but I don’t think that’s what Hadar is.

Personally, denominational labels never really spoke to me. I often think about a student who once asked Abraham Joshua Heschel what denomination he was, and Heschel replied that he was “not a noun in search of an adjective.”

What has worked best at Hadar?

We have succeeded in taking what is most powerful about a traditional beit midrash and then bringing academic Jewish studies as a tool but not as an ideology to help us understand Jewish texts. That has been very powerful for a lot of students—having a beit midrash where no intellectual struggle and no personal story is off the table.

No doubt, as a Jewish educator and parent, you have thought about how Tanakh should be taught not just to adults but also to children and teenagers. Recommendations?

There is enormous value in being shown explicitly the ways that different texts give expression to different modes of religious life. What I mean is this: There was a time in my life where I honestly thought that major questions about God and God’s role in the world were distinctly modern, and then I discovered the book of Psalms and realized how wrong that was. Many psalms are about wrestling with the fact that the story Tanakh tells about the world—that there’s a good God who orders the world in the language of wisdom literature, the just get their deserts, and the wicked get their deserts—doesn’t seem to be true. I mean, you take a walk in the world, and you realize that the world doesn’t look like that at all. That’s not a modern question. Already the Bible is wrestling constantly with its own theology. There’s something very powerful about that.

The text that I put in front of people is Psalm 44, the angriest chapter in Tanakh. It is basically this expression of bitter disappointment at God for having failed the Jewish people. It is just so moving and painful, and it upends all of your simplistic assumptions about what the Bible could and couldn’t say.

If you would, offer me a few thoughts on the future of American Jewry.

That’s a little, light-hearted question! The first thing I would say, as an educator, is that if liberal Judaism is going to have a future in America, it’s going to have to work extremely hard on literacy. American Jewish religious culture is texturally thin; its knowledge of the language of Torah is weak.

I would also say that the American Jewish inability to have any kind of conversation about Israel that does not devolve, in moments, into casting aspersions is catastrophic. It is leading to really profound fissures in the community, and I’m not sure anybody really knows how to fix it. One of the things I find myself thinking about a lot is to what extent that dysfunction is unique to the Jewish community and to what extent it is merely a reflection of contemporary America, which is, of course, completely dysfunctional in its discourse.

I would say, on a very personal note, I would love to get to the point where Jewish life was not so expensive that it feels like you have to be wealthy to be fully inside the Jewish community. There is something problematic in that.

How do we make Judaism affordable for the masses?

I’ll say something that will not win me a lot of friends. I am not sure that American Jewish philanthropists should be endowing the 15th chair in Jewish studies at Random University before they make it possible for kids in their local communities to get a Jewish education or go to a Jewish summer camp. Academic Jewish studies is not—for all of its value—a substitute for mass Jewish culture.

What’s next for you?

I’m writing a book that is temporarily entitled Judaism Is About Love. At a certain point in American Jewish history, American Jews began defining Judaism as whatever they thought Christianity was not. They would say things like, “Christianity is a religion of love, but Judaism is a religion of law or justice.” Another absurd example: “Christianity is a religion of the afterlife; therefore Judaism doesn’t believe in the afterlife.” But that’s completely absurd and false. I’m trying to reclaim love as a central if not the central category of Jewish theology, of Jewish spirituality, and of Jewish ethics.

Do you think Christians will want to read this new book?

Christian scholars of the Hebrew Bible have actually begun to talk like this quite a bit. Just today, I was looking at an essay by a pretty conservative evangelical—he would call himself an Old Testament scholar—who argues that viewing the God of the Hebrew Bible as a God of judgment, as opposed to a God of love, is a stereotype that should be put down for all time, put to rest as a lie. That was really striking. Now, that didn’t stop him from going on and complaining about Jewish legalism and all this other horrible, anti-Judaic stuff, but there is some movement in the Christian world on this.

One of the most gratifying things about The Heart of Torah is that it has begun to find audience in parts of the Christian world, and that’s been really moving. Professor Richard Middleton at Northeastern Seminary has started assigning the introduction to his students as what he calls a “Jewish ethical version of the Christian ‘rule of faith.’” He says a number of his seminary students, on his recommendation, have purchased copies of my book for themselves. That’s amazing to me.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Who Is Man?

Two new books on sin and temptation.

Missed Connections

Joseph Skibell, like any good historical novelist, is a dybbuk—he animates the dead.

Not a Nice Boy

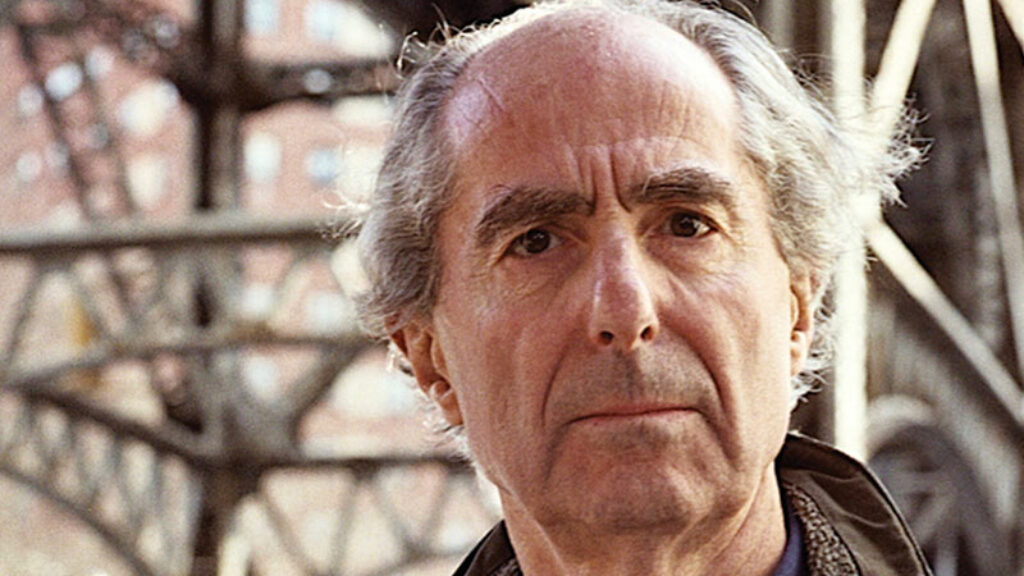

To every author who seemed too cautious—which was nearly every author he knew—Roth gave the same advice. “You are not a nice boy,” he told the British playwright David Hare. His friend Benjamin Taylor’s memoir is . . . nice.

Fauda: The Wages of Chaos

Fauda, which takes its name from the Arabic word for chaos, opens in an adrenaline rush of noise, confusion, and jagged camerawork.

Gary Goldberg

Wonderful interview! I am deeply intrigued by the concept of Judaism as a religion of self-less love, or 'agape.' I have recently been fascinated by a perceived convergence between the phenomenological philosophy of the great French-Jewish philosopher, Emmanuel Levinas, and the breath-taking evolutionary metaphysical vision of the father of American pragmatism, Charles Sanders Peirce--who Alfred North Whitehead referred to as the 'American Aristotle.' The pinnacle of Peirce's metaphysics is what he called 'evolutionary love' that is involved at the mediational level of evolutionary process--the Third level of 'agapasticism.' It heralds the capacity of agape to literally hold the universe together and prevent it from flying apart. The First level is 'tychasticism' which is the fundamental 'tohu vavohu'--the chaotic foundation upon which all else that must channel the creative capacity of the foaming foment is built. The Second level is 'anancasticism' which is the level of raw brute force--the 'Newtonian paradigm' of purely deterministic mechanical law-bound 'necessitarianism.' The 'clash' of a world devoid of the mediational power of agape--the self-less love of other--as distinct from eros--self-serving insatiable desire. In Levinasian terms, the latter is the 'longing FOR the other'--the desire to 'totalize'--while the former is the inherent command to substitute oneself for the other in the agapastic act--capitulating to the infinite alterity constituting the 'face' of the other, the other that resists any attempt to totalize with analytical reason. Levinas integrates the road from Athens that eventually gave birth to phenomenology, with the road from Jerusalem with its commandments to not covet, to not capitulate to self-serving desire, but instead to 'love the other as yourself' or, to re-phrase, and radicalize in a Levinasian frame, to 'love the other who IS yourself.' This is the message of Hillel the Elder, Jesus of Nazareth, and the message of compassion that runs as a common thread through the majority of the world's faith traditions. Michael Fagenblatt addresses some of this in his book, 'A Convenant of Creatures. Levinas's Philosophy of Judaism.' Really looking forward to how Rabbi Held re-frames Judaism in the context of a religion of Chessed.

Gary Goldberg

One more observation informed by the triadic semiotics of Charles Sanders Peirce who railed against Nominalism and it's creation of the intractable binary oppositions of modernity, the Clash of necessitarianism and the hidebound logic of the Law of the Excluded Middle and the Law of Non-contradiction... The bane of existence!

Love and Justice are NOT mutually exclusive constructs. They form a complementary pair in the tradition of Neils Bohr's Principle of Complementarity. You can't have the One without the Other. There cannot be Love without Justice and there cannot be Justice without Love. The key is that the dynamics of Love/Justice is not a dialectical Hegelian tussle. It is a necessary coupling whose dynamics are mediated through a semiotic process of unfolding on a temporal continuum. It is a flowing dance in continuity through which potentiality actualizes. It is NOT a battle, a duel between oppositions. It is a dance between complementary partners engaged in covenantal inter-relationship.

gary.goldberg.md

That should have read 'Covenant of Creatures. Levinas's Philosophy of Judaism' by Michael Fagenblat. A really fascinating and thought-provoking book for anyone looking to explore the connection 'between'--the veritable 'crossroads' of religion, theology and secular philosophy.

Reviewed here by Kenneth Seeskin in the 'Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews'... https://ndpr.nd.edu/news/a-covenant-of-creatures-levinas-s-philosophy-of-judaism/

Apologize for the spelling errors...