All or Nothing?

If you picked an Orthodox person off the streets of Lakewood or Monsey to describe the life of someone who has gone religiously astray, or “off the derech,” they might describe the life of Larry, the flawed protagonist of Nathan Englander’s latest novel, kaddish.com, though perhaps not in detail. The more sheltered would be unlikely to imagine “the everyday depravities filling the alternate reality that ate more and more of sad Larry’s time.” Counting the ways in which he has suffered during the shiva week for his father, Larry lists his foregone fleeting pleasures, congratulating himself for going almost a week, almost, without pornography.

For nearly a week, despite his small rebellions, he’s smoked neither cigarette nor joint, he hasn’t had a stiff drink (or three), he hasn’t once sunk into the living-room couch to binge eat and binge watch, gorging on junk (visual and edible) until the stomach acid burned and his brain conked out.

Englander, whose earlier novels and short story collections established him as a creator of sharply drawn characters, has created in this protagonist both a cranky, curmudgeonly nebbish and a flat social type. Engrossed in his own loss, Larry is unwilling to undertake the commitment to say Kaddish for his father, a demand made clear to him by his still-frum sister Dina. This is 1999, in the midst of the first dot-com bubble, so Larry searches out kaddish.com, a website where Jews without the inclination to pray three times a day, seven days a week, for the elevation of the souls of their departed, can, for a fee, enlist those who would pray with regularity in any case, “like a JDate for the dead.”

With the web form completed and the duty discharged, kaddish.com jumps to the present day, where Larry has returned to the fold, transformed from “sad Larry” to pious Shuli, “a seventh-grade Gemara teacher at the very yeshiva where he had gone,” living in Brooklyn, married to Miri, father to a boy and a girl born just a year apart. He is now so frum that he requires the secretary of the school to print out emails from parents and type his replies for him; he does not allow himself temptations of modernity, not even a flip phone. The transformation—again a story of an easily recognizable type—is seen only in hindsight, as Shuli tells his story of “coming home” both to inspire those who might be poised to make a similar move as well as to prove to the faithful the rightness of their choices.

As Englander no doubt knows, it is impossible to read kaddish.com without thinking of his own well-publicized background as a yeshiva student who turned away from Orthodoxy. It is similarly impossible not to contrast the tenderness with which Englander draws his Orthodox characters in the present novel with the pointedly harsh judgments of Orthodox characters in the stories that made him famous, from the hypocritical Rabbi Baum of “Reunion” to the lying, grasping Ruchama of “The Wig” in his debut story collection, For the Relief of Unbearable Urges. In this new book, the Orthodox characters are, while flawed in ordinary human ways, patient, understanding people.

To reduce kaddish.com to a middle-aged Englander working out his own issues with Judaism and coming to a mature accommodation would be too easy, but it is difficult for a reader to ignore the breadcrumbs. Here is Reb Shuli talking to a student who is testing the limits of observance:

“Because with rebellion, it can also be a way to acknowledge the importance of the thing we rebel against.” Reb Shuli stops himself there, but Gavriel doesn’t respond.

“What I’m trying to say is, sometimes the rejection is a way to let people know that the thing we reject truly matters. It is its own kind of faith, even if it’s the opposite of faith.”

In pitting secularism against religiosity as all-or-nothing propositions and in dividing the book so sharply into two sections, Englander administers what he has often called a fictional Rorschach test, and perhaps readers who are further than I am from the streets of Lakewood will read it differently. But he has also said that as a reader, he himself revels in contradiction. As he told Ted Hodgkinson in an interview for Granta:

It fascinates me how an individual has to hold so many opposing realities in his or her head simply in order to survive. I’ve been using the phrase “bifurcated brain” for this; by which I mean a person’s ability to believe something and its contrary at the same time. When I think back on the short stories that have had a profound impact on me—whether it’s Philip Roth’s “The Conversion of the Jews,” or “Goodbye and Good Luck” by Grace Paley or “The Story of My Dovecot” by Isaac Babel—they all leave me with a sense of those conflicting realities being challenged.

In kaddish.com, Englander creates his own conflicting realities. How, for example, are we to experience Dina’s heartbreaking plea that her brother be the one to say Kaddish?

“You don’t have to be religious,” his sister says. “You don’t have to believe. You can think nothing and feel nothing and eat your cheeseburgers every meal.” . . . “But you can’t skip a minyan. Not once. Not ever. It’s what our father expects—what he expects right now from Olam HaBa. Because it’s that alone, what you do, what you say, that sets for our father the best conditions in the World to Come.”

How can these prayers mean so much to her, and how can they possibly mean anything to God, if she knows Larry will recite them resentfully as a litany of meaningless syllables? And how are we to reconcile the real and recognizable kindness and warmth of the Orthodox world Englander evokes with the violent and callous yeshiva rebbe who hit young Larry so hard for not being able to answer a question that he was left with a permanent scar?

And how, finally, are we to understand Larry/Shuli himself? If Englander is right that human survival is predicated on not choosing but on holding open the possibility that two opposites are true, then perhaps a selfish porn addict indifferent to his only sister’s grief can become a loving family man, a caring teacher who deals sensitively with his students’ transgressions, large and small. And perhaps this upright model of Jewish propriety can, when the plot propels him from his yeshiva to sleeping rough on the streets of Jerusalem in an attempt to finally fulfill his obligation to his father, still be so impulsive that he threatens the life he has built. As far as Shuli has traveled, he is still, to some extent, “sad Larry,” wearing different clothes, pursuing different goals, but still chafing at imposed obligations, still tending toward excessive monomania, and still willing to upend the life of others to pursue his own obsessive desires.

kaddish.com is a small novel, easily read, but Englander has nested inside it questions within questions and opposites within opposites.

Suggested Reading

Harold Bloom: Anti-Inkling?

It’s a bit surprising to come across Harold Bloom’s confession that the literary work that has been his greatest obsession is not, say, Hamlet or Henry IV, but a relatively little-known 1920 fantasy novel.

Is Love Stronger than Death?

Near the outset of his book about mortality, Hillel Halkin has fallen into a grave, gazed at the remnants of a skull, succinctly described ancient Israelite burial practices, and vividly illustrated the ritual and material basis for that resonant biblical phrase in which the dead are “gathered to their ancestors.”

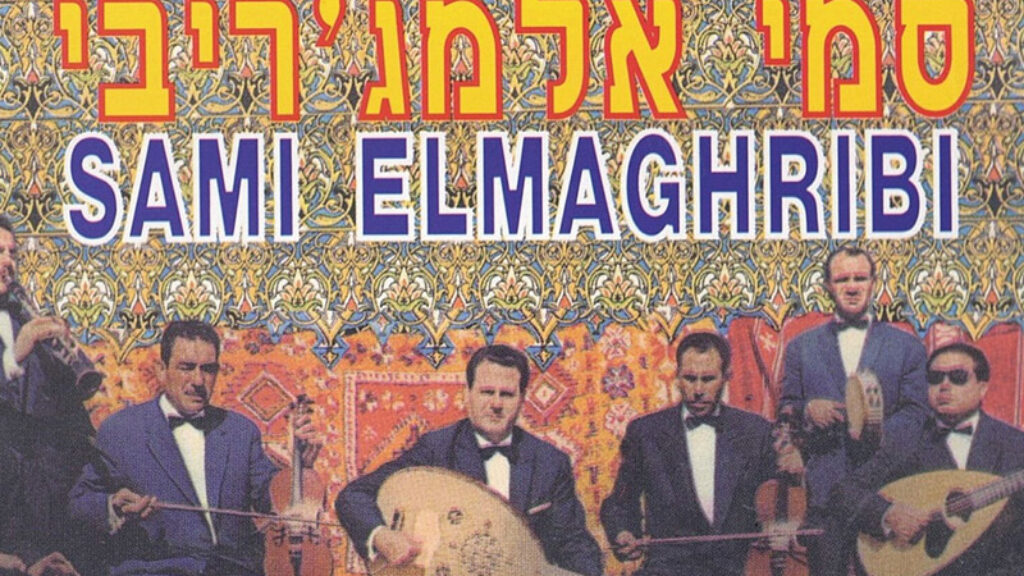

Missing Notes

There was a time when Jewish artists set the tone for North African music, but now only echoes remain.

The Old Country, Twice Removed

My grandfather had a way of mentioning the Kiev guberniya (province) that made it sound to me, when I was a boy, like it was our place in the Old Country—and more than half a century later, it still does.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In