Is Love Stronger than Death?

Early on in this charming, frankly vulnerable, and deceptively deep book about death, Hillel Halkin tells the story of a discovery he made on the grounds of his property on the southern slope of the Carmel mountain range:

Exploring an overgrown patch of ground, I lost my footing, plunged several feet through some bushes, and landed in a hidden depression. Facing me was a low entrance cut into rock, topped by a crudely worked lintel. I cleared the dirt blocking it, crawled inside and found myself in a rectangular chamber some eight feet by twelve. Niches were hewn in the walls.

When he returned with some friends to explore the cave, they found “the bottom half of a jaw, yellowed like old parchment.”

She had died, perhaps two-thousand years ago, perhaps a bit more. The heavy stone sealing her family’s burial cave, known in Hebrew as the golel or “roller,” was pushed away; her body, wrapped in shrouds, was laid inside; the roller was rolled back into place. When enough time had gone by for her flesh to decompose (according to later Jewish tradition, this took a year), the cave was reopened and her bones were collected and placed in a niche with those of her ancestors. She had been gathered to them.

Although Halkin is more than capable of writerly pyrotechnics, these are plainly written passages, but look at how much he has accomplished with them. Near the outset of a book about mortality, he has fallen into a grave, gazed at the remnants of a skull, succinctly described ancient Israelite burial practices, and vividly illustrated the ritual and material basis for that resonant biblical phrase in which the dead are “gathered to their ancestors.” And yet the reader feels no artifice, hears no creaking of thematic machinery as the foundations of the book are being settled into place. One might just as well be sitting with the author in the living room of the house he later built on that land, looking out the window and hearing him reminisce about his early days here in Zikhron Yaakov, and how once he fell down a hole right about there . . . and the memento mori moment passes lightly by.

That it would be important, even comforting, for an ancient Israelite to know that his bones were resting next to those of his ancestors made sense, Halkin and others argue, in a tribal society in which one could not conceive of oneself in isolation from one’s family, clan, tribe, or people. “This is why,” he goes on to say, “the Bible sometimes alternates . . . between singular and plural language” in addressing its readers. It is also why the biblical subject reaps blessings from his ancestors’ righteousness and is held accountable for their sins, and why the most dreaded condition in the Bible is childlessness:

Being childless is not just a matter of thwarted parental instincts or of the drearily empty house that a married couple must awake to each day. It is breaking the chain, losing one’s only prospect for immortality. This is most probably the meaning of the “cut-offness” that the Bible never defines.

But was continuation of one’s line really the “only prospect for immortality” for ancient Israelites? Were they as this-worldly as all that?

William Warburton, the 18th-century bishop of Gloucester, once argued that the Bible was a divinely inspired document precisely because it didn’t hold out the promise of an afterlife as any merely human document surely would have. Halkin might agree, though with at least two caveats. First, he is firm in his disbelief, so the most that he would be likely to allow is that the Bible is heroic in its rejection of mythological wish fulfillment, and, second, as he notes, the Israelites did, in fact, know the place into which one descended after death. It was called She’ol.

But they, or at least the Bible, didn’t talk about it much. It seems to have been the subterranean place where the incorporeal—or perhaps just barely corporeal—shadows of once-living bodies went to sleep, and from which they are occasionally (and illicitly) raised, but it was neither Hades nor the Elysian Fields. And, like the grave itself, it would appear to have been neither a punishment nor a reward to go there, just an inevitability.

If She’ol is all there is to individual immortality in the Bible, it doesn’t seem like much to look forward to. And, indeed, when the biblical God makes promises they are not of some ethereal afterlife, and certainly not of She’ol, but of children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and beyond. If descendants are not quite the only prospect for immortality in the Bible, they would certainly seem to be the most important.

Of course, later Jews did not read the Bible this way. As Halkin writes, “The First Temple’s destruction . . . and the mass exile and loss of national independence that followed, put an end to the old sense of life as a slow, organic passage in which each generation bequeathed itself to the next.” To this political explanation for the development of new individualistic ideas of the afterlife, Halkin adds a social one: In the mobile, urban society of late antiquity, “I could not assume that I would have anything in common with my own progeny. The field I cleared might not be farmed by them. The house I built might be lived in by others. My life was now uniquely my own.” And so new, more individualistic ideas of the afterlife developed and then were read back into the biblical text.

Although Halkin doesn’t mention it, his account of the rise of individualism in ancient Israel echoes early 19th– and 20th-century sociological thinking, in which our modern world is described as the product of a shift from small, intimate, organic communities to big, anonymous cities in which one was on one’s own. This doesn’t mean that there isn’t something to both conjectures, but it seems to me impossible (or at least unfalsifiable) to say just how much. However, Halkin isn’t writing an explanatory history of Jewish ideas of the afterlife. He has given himself a different, more pressing task: to think through the various scenarios his tradition has set out for “the world to come” and re-inhabit them, try them on for size.—Might I hope for this? And what would it be like?

The two scenarios set out by the Rabbis were that the individual soul survives death in a world- to-come less shadowy than She’ol, and that, eventually, when the Messiah comes, there will be an earthly resurrection in which the children of Israel will return to their revivified bodies. Depictions of that first, disembodied afterlife varied from Rav’s austere world to come in which “there is no eating, no drinking, no procreation, no commerce, no jealousy, no hatred, no rivalry, and the righteous sit with crowns on their heads and enjoy the radiance of God’s presence,” to vivid descriptions of reward and punishment, and ornate visions of the inhabitants of the third heaven. (The third of seven, of course, and corresponding, as Halkin—always the helpful guide—tells us, to the brightest planet, Venus.)

In a famous talmudic discussion as to whether those buried outside of the Land of Israel will be resurrected, and, if so, how they are supposed to get home, Rabbi Il’a suggests that their bones will tumble from their diasporic graves through special tunnels back to Israel. “I try to picture it,” Halkin writes:

All I can think of is the noise. At first it’s an irregular clatter as the ground opens beneath my grave and my bones chute into a sloping passageway barely large enough to crawl through and begin tumbling down it. . . . The noise grows louder. Ahead is a sound like the rattle of a train. The tunnel is entered by another, and bones from a second graveyard hurtle into it. Bone knocks against bone. Bone sends bone flying. My forearm is caught in someone’s pelvis. Someone’s vertebrae ride on my skull.

He imagines the bones spilling out onto the shores of the Dead Sea, “heaped everywhere, like seashells,” and invokes Ezekiel’s famous vision of the resurrection of dry bones into an army of flesh and blood. “I stretch out an arm,” Halkin writes, “It’s mine. A leg. Sore but my own. . . . Four thousand feet above me, to the west, rises the Mount of Olives.”

The Hebrew word Rabbi Il’a used to describe the tumbling of those bones was the onomatopoeic Hebrew word “gilgul,” and, in a curious transformation, when reincarnation entered Judaism it did so under that name, which can also mean a cycle. Halkin has some fun with the legends of the kabbalist Rabbi Isaac Luria who could, apparently, read the previous lives of people and, on occasion, animals just by looking at them. (A rat, for instance, turned out to have been a Jewish informer in his previous life.) But the notion of reincarnation itself does not take hold of him.

Almost precisely midway through the book, the reader finds Halkin pacing his small second-floor study in an anti-Cartesian mood. He is thinking about life after death and reincarnation, but also about the pain in his heel, the ache in his back, and the light spilling through the window, and suddenly both the notions of living disembodied in the world to come or being re-embodied in this world seem equally ludicrous:

How will my soul get along without its body? It’s used to it. It’s shaped and been shaped by it. Why would it want another even if it could have one? Nothing would fit. We wouldn’t be me. It would be like sleeping with a strange woman instead of with my wife. . . . I return to my desk and write: the absurdity of resurrection—the only hope.

The absurdity of resurrection is something the medieval philosophers worried over. Saadia Gaon tried to make it plausible. (Where will we put all of them? Do we have enough space in the Land of Israel? What about air particles that belonged to more than one body?) Everything in Moses Maimonides’ rationalist world-picture made resurrection not only implausible but undesirable (why would anyone want to be anything but a disembodied mind?), so he simply stipulated that it was an unshakeable tenet of faith.

What Halkin realizes at the end of his anti-Cartesian meditation is that there is—whatever its philosophical and scientific absurdity—real human wisdom in the rabbinic doctrine of resurrection. What we will miss is this body, this world, this life, so the promise of something wholly different offers little consolation.

As Halkin mentions near the outset of this deeply personal book, he has already passed the “threescore and ten” years promised in Psalms, and neither he, nor any of us, expect to live the extra half-century granted to Moses. That, after all, is the point of wishing someone a long life by saying “ad meah ve-esrim” (until one-hundred-and-twenty), the traditional phrase upon which his book title plays. But this is not a death-haunted book, or, if it is, it is not, despite a lifelong hypochondria, really the prospect of his own extinction that haunts Halkin.

He writes movingly of his parents’ passing, especially his mother’s, and of his ambivalence about reciting the Mourner’s Kaddish for them. (His father was a distinguished scholar, who, though Halkin doesn’t mention it, translated Maimonides’ “Treatise on Resurrection” near the end of his life.) And he admits frankly that he cannot imagine surviving the loss of a child, though, of course, having lived in Israel for the past five decades, he has seen that happen far

too often.

But it is Halkin’s abiding love for his wife that spurs him toward a belief in some kind of immortality. “How can a love like ours simply disappear?” he asks her, “Doesn’t it have to go on existing somewhere?” Despite his biblical this-wordliness, the experience of love has given Halkin an intimation of eternity. (Here, as throughout After One-Hundred-and-Twenty, there are points of contact with Halkin’s moving 2012 novel about a love that should have lasted forever, Melisande! What Are Dreams?)

In a less modern world, or one governed by literary symmetry, Halkin and his wife—interestingly, he never names her in the text—would, after they reach one-hundred-and-twenty, leave their land on Mount Carmel to their children, with instructions to be interred in the burial cave that Halkin discovered all those years ago. But, as he explains, the property is too valuable not to sell to developers sooner or later, and, anyway, his daughters are happy in Tel Aviv.

Near the very end of the book, Halkin quotes the Yom Kippur prayer, which asks “What is man?” and answers, “Like the jar that breaks, and the grass that withers, and the flower that fades . . . and the dream that is gone.” To which he poses the further, almost hopeful, question, “If life is a dream, what does that make death?”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

If This Is a Man

Primo Levi often claimed that he was first and foremost a chemist and not a professional writer, but anyone who reads him with care will be moved by the sober lucidity, subtlety, concision, and analytical power of his prose.

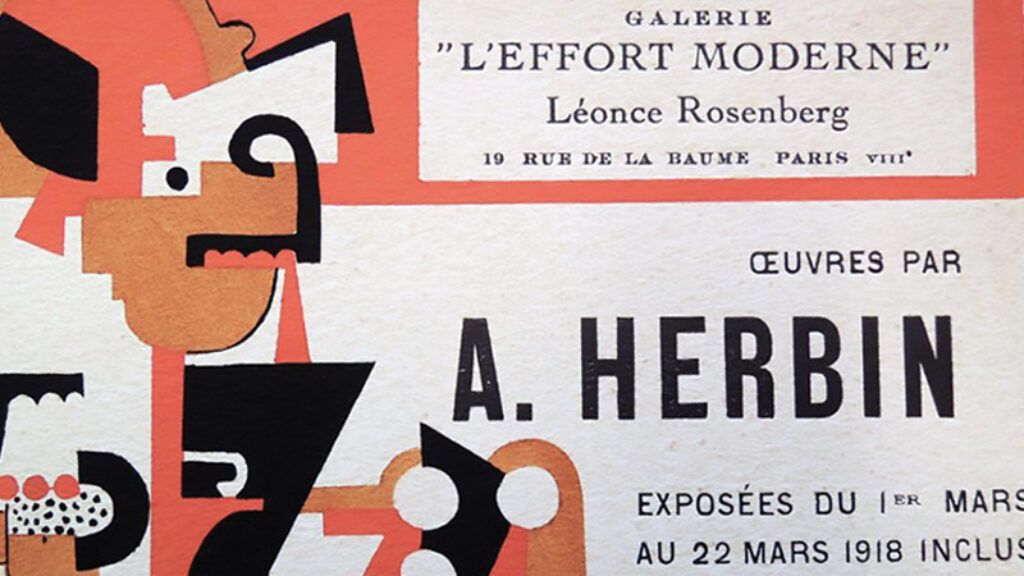

The Art of the Dealer

"What would have happened to us," Picasso wondered, " if Kahnweiler had not had a business sense?"

Dress British, Think Yiddish

Stanley Kubrick was a New York Jew, fascinated with photography, jazz, and chess. He took evening classes at City College and studied at Columbia with Lionel Trilling.

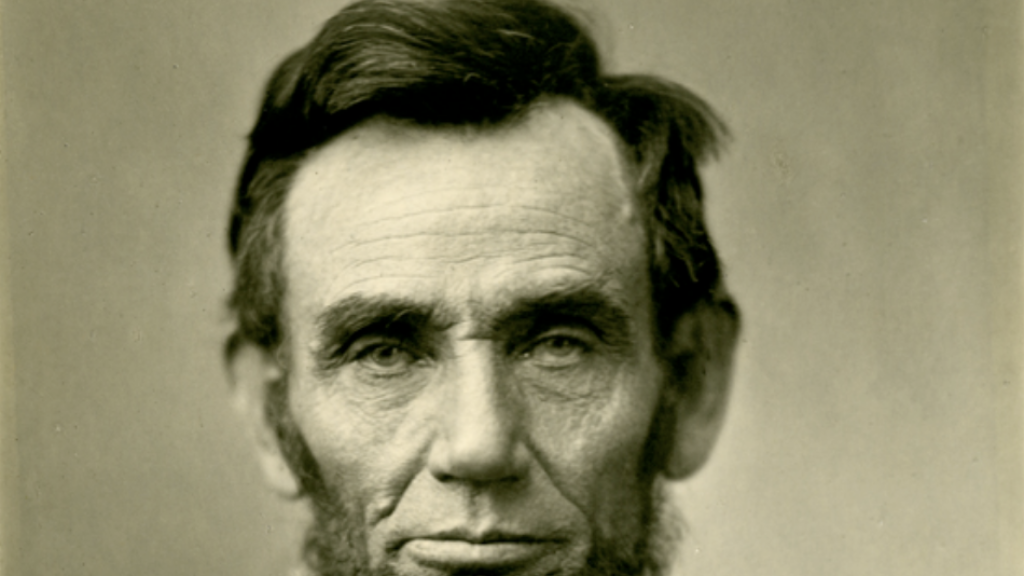

Was Lincoln Jewish?

Abraham Lincoln became a saint for American Jews. But was he also "bone from our bone and flesh from our flesh"? One rabbi thought so.

[email protected]

Sounds like a great book