The Fire Now

A few months before I graduated from college, I received my first death threat from an anti-Semite. Although I am not Jewish, I had become a pro-Israel activist on campus. The threat came in the form of a six-second YouTube video. First it showed me holding an Israeli flag, then a picture of someone in a hospital, and finally a picture of a tombstone; the accompanying audio called for the use of bullets—six to be exact—to take me out.

It was the first time I experienced anti-Semitism, not as a historical phenomenon to be discussed in a classroom, or even as an alarming contemporary news item (anti-Jewish violence in Paris, genocidal threats from Iran, or hateful words from American radicals, right or left), but as a palpable danger that was, to quote the subtitle of Deborah Lipstadt’s important new book Antisemitism, “here and now.” A sense of dread entered my dreams and stayed with me even after I woke up.

The subject of anti-Semitism is hardly new to Lipstadt. A distinguished historian at Emory University, she has written books on the American press during the Holocaust, the phenomenon of Holocaust denial, and the Eichmann trial. She was also famously sued in British court by Holocaust denier David Irving in 1996, and her book on the experience was adapted for the 2016 film Denial. Nonetheless, as she writes in the introduction, this compact primer on present-day Jew hatred is, in some ways, her most unsettling book:

As horrific as the Holocaust was, it is firmly in the past. . . . Though I remain horrified by what happened, it is history. Contemporary antisemitism is not. It is about the present. It is what many people are doing, saying, and facing now.

In fact, the book is, unfortunately, even more timely than she could have known. The massacre of 11 Jews praying at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh occurred while her book was being printed, and, as I write this week, Lipstadt has been interviewed on NPR and elsewhere about Representative Ilhan Omar’s public insinuation that Jews have dual loyalties and the ensuing crisis in the Democratic Party.

Rather than reporting directly on contemporary anti-Semitism or writing a history of its origins, Lipstadt has done something much more surprising and effective. She has chosen to write a kind of epistolary novel in which she corresponds with Abigail, “a whip-smart Jewish student . . . trying to understand the phenomenon of antisemitism,” and an academic colleague Joe, a non-Jew who “teaches at the university’s law school” and who “has a deep appreciation for both the successes and travails of the Jewish people.”

Abigail is not so much as physically afraid—though she and her fellow Jewish students are taking precautions on an upcoming group trip to Europe—as she is distressed. As she says, “I have no reason to fear for my physical safety here on campus. I feel comfortable as a Jew, except maybe when Israel is the topic of discussion.” Joe, on the other hand, is puzzled. He is troubled by the heightened animosity in American civic life, and he’s not quite sure where anti-Semitism fits into the picture. “Antisemitism,” he writes, “is something I’ve long abhorred, but also something that I fear I do not fully understand.”

Lipstadt introduces her two correspondents (who, she says, are each “composites of many people”) to each other and hits Reply All. Their correspondence on anti-Semitism covers everything from the spelling of the word—Lipstadt prefers the all-lowercase, no-hyphen option because it doesn’t endorse the racist idea of “Semites,” and because “[s]omething this absurd does not deserve a capital letter”—to its deep ideological and religious origins.

In these calm, lucid letters, Lipstadt shows Joe and Abigail how anti-Semitism currently emanates from both the Right and the Left, and underlines the moral failure of members in each of these political spheres to recognize and tackle the problem in their midst. She quotes the editor of the neo-Nazi Daily Stormer, writing shortly after President Trump’s election, “Our Glorious Leader and ULTIMATE SAVIOR [sic] has gone full-wink-wink-wink to his most aggressive supporters. After having been attacked for retweeting a White Genocide account a few days ago, Trump went on to retweet two more.” Even if such retweets don’t prove what the writer thinks they do—President Trump himself is clearly not an anti-Semite—the president’s refusal to, in Lipstadt’s words, “castigate, much less mildly criticize” such supporters without equivocation has undeniably encouraged them.

By contrast, when anti-Semitism comes from the Left, it tends to be masked by an ideology that preaches social justice and is ostensibly in pursuit of helping the underprivileged. This, in my view, is a far more sophisticated form of bigotry, sweeping up well-meaning students and politicians with its rhetoric. It is the ideology Abigail faces on campus, and it is what British Jews face in Jeremy Corbyn and the current Labour Party. If President Trump sometimes winks at anti-Semites, Jeremy Corbyn breaks bread with them, invites them into the home, and is proud to call them friends. The formula for this, Lipstadt explains, is a coupling of “sympathy for anyone who is or appears to be oppressed . . . with . . . a class- and race-based view of the world. Anyone white, wealthy, or associated with a group that seems to be privileged cannot be a victim.”

In other words, combine racial essentialism—the belief that virtue is derived from and inherent to skin color—with class warfare and a belief that being an underdog suggests ethical superiority—and you can justify anything. In the case of Corbyn, it has justified laying wreaths in honor of the members of the Black September faction of the PLO who massacred Israeli athletes at the 1972 Olympics, speaking warmly of and to Hamas, and essentially purging “Zios” from the Labour Party. Since the Jew, in England and America, is often white, Ashkenazi, and a member of the elite, she must be an oppressor. And so too must the only Jewish state and all of its inhabitants.

This moral confusion is a product of the foundational tenets of current leftist ideology. In one particularly interesting letter, Joe asks what to do about people who do not recognize anti-Semitism when it comes from the social justice Left instead of the neo-fascist Right. In her response, Lipstadt points out that if, in the name of achieving equality for all, one finds it acceptable to “include blanket statements about Jews in their excoriation of wealthy capitalists who oppress and exploit the poor, who imply that Jews exert undue influence on the media, who deny that Jews can be the victims of race-based hatred in the same way that people of color are, and who include offensive, hate-filled Jewish stereotyping in their criticism of Israeli government policies regarding the Palestinians,” then one is not promoting equality but making a mockery of the term. One of the great features of Dr. Lipstadt’s book is that it helps the reader to see the underlying dysfunctions in democratic societies that allow anti-Semitism to flourish. These include movements to suppress free speech, the “yes-but” excuses for Muslim anti-Semitism in Europe, and the reflexive erasure of the particularly anti-Semitic nature of attacks on people, institutions, and, of course, one particular state that were clearly targeted because they are Jewish.

Lipstadt’s book manages to cover a lot of hard and depressing ground in an engaging, thorough way, yet I did leave it wishing for a bit more anthropological, or perhaps spiritual, depth. While Lipstadt is trenchant about who the anti-Semite is, she is less interested in the question of why he is. “It’s not antisemitism that is inconsequential, it’s the antisemite himself,” she writes. But I’m not so sure.

In The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin wrote, “White people in this country will have quite enough to do in learning how to accept and love themselves and each other, and when they have achieved this—which will not be tomorrow and may very well be never—the Negro problem will no longer exist, for it will no longer be needed.” If, as Lipstadt persuasively argues, anti-Semitism is ultimately a conspiracy theory, the belief in an all-powerful, nefarious cabal of Jews tirelessly working to uproot and destroy the nations of the world, it is worth asking why the anti-Semite suffers from such acute paranoia. A person who believes himself to be both a perennial victim anda hero fighting against a cosmic evil does not truly know himself. What spiritual malady does belief in the “Jewish problem” solve?

Lipstadt writes that “[a]ntisemites must be fought . . . but they are people of no consequence.” As a proud Jew and historian who has spent her life studying and fighting those who irrationally hate her people, she is under no obligation to occupy herself with their spiritual problems. And yet, isn’t it often precisely because they are people of no consequence that they often take their wretched sense of dislocation and anguish out on others? As former skinhead Arno Michaelis recently wrote,“In the absence of love’s light, hate can be exciting, seductive. It beckons you and sends torrid, empty power coursing through your veins. . . . Every minute you spend hating someone is a hole in your life.”

Deborah Lipstadt’s book shows what the anti-Semitic hatred of such people looks like now, from Holocaust denial to the denial that Jews are a nation. One hopes that it will be read by the thousands of “Abigail”s and “Joe”s who are unlikely to be tempted by the first form of anti-Semitism but will undoubtedly be tempted by the second. This is, unfortunately, a necessary book.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Lilith and the Knight

Demons, dragons, and a “Tel Aviv hipster in King Arthur’s Court.”

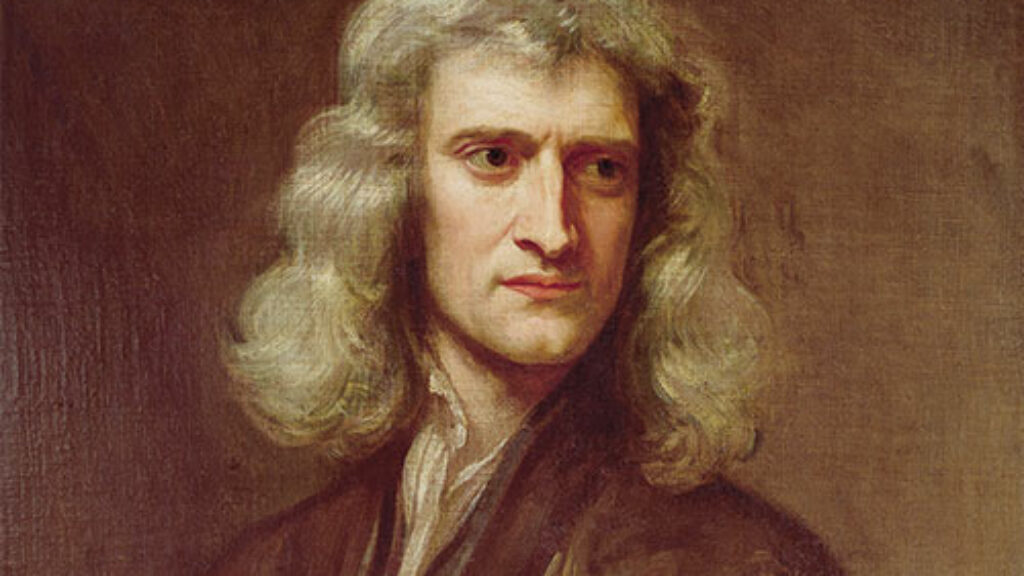

Maimonides, Stonehenge, and Newton’s Obsessions

It takes a bit of a genius to successfully study a genius, and in this case one must first master the millions of words Isaac Newton wrote about natural theology, doctrine, prophecy, and church history.

Scribes without a Torah

Julien Benda’s The Treason of the Intellectuals is one of those books that is famous even though no one actually reads it. Can it help keep those whose business it is to think in public on the straight path? Did it help Benda?

The First Debate Over Religious Martyrdom

The name of God is sanctified when life is preserved, not when it is proclaimed great an instant before life is obliterated.

Martin Berman-Gorvine

I enjoy Chloe Valdery's insightful work, but I must dissent from her flat assertion that President Trump is not an antisemite. As any student of bigotry knows, the protestation that one has lots of friends and even family from the target group is almost automatically suspect, and is certainly no guarantee that one is free of prejudice. Trump has been reliably quoted as saying that he wants short guys with yarmulkes counting his money, which is certainly an antisemitic expression. When Trump said that he considered the torch-wielding neo-Nazis in Charlottesville to be "very fine people," he was doing something more than just "winking" at them, in Valdery's terms. An America in which the GOP is in thrall to this nationalist-populist antisemite, and most Democratic elected officials feel bound to defend a Congressional antisemite merely because she is black and a Muslim, is an increasingly menacing place for a Jew to live in.

Richard Genirberg

Now that Pres. Trump has demonstrated greater support for Israel than any American president, perhaps since Truman, we should recognize any attempt to characterize Mr. Trump as antisemitic as ignorant or insidious. Unlike cowardly presidents since Bill Clinton, Pres. Trump moved the American embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, as required under American law; he approved of Israel's strategically crucial retaining of the Golan Heights, which denies a convenient platform from which terrorists could hurl rockets at the hated Zionist entity; and just last week the Secretary of State announced that the U. S. would not label Jewish towns in the West Bank as unlawful. He has welcomed his Jewish son-in-law into his family and into his administration. Growing antisemitism is a genuine concern, especially in Europe, but also in the United States, but not in the Trump White House. We should recognize any disparaging of Mr. Trump as antisemitic as partisan political bigotry.