The Gray Lady and the Jewish State

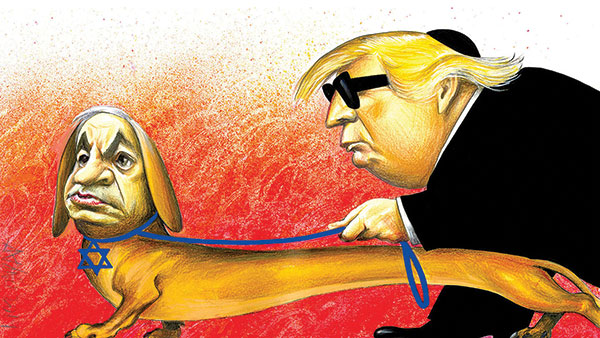

In late April 2019, the New York Times international editionpublished a cartoon depicting a blind, kippa-wearing President Trump being led by a dachshund with a Jewish star around its neck. The dog’s face was a distorted caricature of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s visage. The message was indisputable: Israelis qua Jews, despite being the national equivalent of lapdogs, have the unique ability to blind presidents and shape political events. Beguiled, not only does Trump do their bidding, but he is, like the other unwitting victims on the world stage, blissfully unaware of what is going on. The cartoon gave vivid expression to the conspiracy theory, or rather myth, that is at the heart of anti-Semitism and did so in an image that, as was widely noted, could have appeared in Der Stürmer. How did it end up receiving the New York Times’s imprimatur?

Apparently, a single midlevel editor for the international edition of the paper chose the cartoon from a syndication service to which the paper then subscribed. Subsequent events followed a familiar pattern. The paper, after being inundated with outraged comments, including some from its own staff members, issued a short apology in the form of an editor’s note: “The image was offensive, and it was an error of judgment to publish it.” Eileen Murphy, a New York Times spokeswoman, added a subsequent statement on behalf of the Opinion section of the paper, identifying the cartoon as anti-Semitic and saying it was “deeply sorry” for publishing it.

In most cases, that would have been the end of the story, except for the scores of Jewish readers and supporters of Israel who were once again forced to decide whether to cancel their subscriptions. Two subsequent events made this incident noteworthy. Writing in the New York Times, op-ed columnist Bret Stephens scathingly lambasted not only the international edition but his own paper. For Stephens, the publication of a “textbook illustration” of anti-Semitism did not reveal institutional anti-Semitism, but it wasn’t much better than that. It was that the Times, “otherwise hyper-alert to nearly every conceivable expression of prejudice,” could be so, well, blind:

Imagine, for instance, if the dog on a leash in the image hadn’t been the Israeli prime minister but instead a prominent woman such as Nancy Pelosi, a person of color such as John Lewis, or a Muslim such as Ilhan Omar. Would that have gone unnoticed by either the wire service that provides the Times with images or the editor who, even if he were working in haste, selected it? The question answers itself. And it raises a follow-on: How have even the most blatant expressions of anti-Semitism become almost undetectable to editors who think it’s part of their job to stand up to bigotry?

The answer, Stephens wrote, was that anti-Zionism has become so mainstream “that people have been desensitized to its inherent bigotry,” and the Times was complicit in that mainstreaming.

Two days later, in an editorial entitled “A Rising Tide of Anti-Semitism,” the newspaper’s editorial board, the publisher, and the editor of the paper together described the cartoon as “appalling” and “bigoted” and decried the paper at whose helm they stand for “ignor[ing] the lessons of history, including its own.” The editors acknowledged that the paper was “still haunt[ed]” by its failures during the Nazi era, when it “was largely silent as anti-Semitism rose up and bathed the world in blood.” But they did not just point to past wrongs. The editors admitted that, though the paper had shown increased sensitivity to “other forms of bigotry,” it—along with society at large—often dismissed anti-Semitism as a “disease gnawing only at the fringes of society.” “That,” the editorial continued, was “a dangerous mistake.”

The editorial board also declared itself to be “stalwart supporters of Israel,” committed to “good-faith criticism,” which would ultimately strengthen it “by helping it stay true to its democratic values.” Those who remain skeptical now have a solid scholarly study to buttress their opinion. Jerold Auerbach’s archly titled new study Print to Fit: The New York Times, Zionism and Israel, 1896–2016 is a well-researched and, for the most part, damning brief of the Times’s news coverage and editorial attitudes toward Zionism and Israel for over a century.

In a charming little afterword Auerbach, who is a professor emeritus at Wellesley College, tells us that he first became aware of the New York Times when, as a child, his father showed him a picture of Hank Greenberg crossing home plate after hitting the grand slam that clinched the pennant for the Detroit Tigers. Greenberg, it turned out, was his cousin.

A resolute creature of habit, I continued to begin each day with The New York Times as my breakfast companion. Along the way, I realized that the Times had a Jewish problem. This book is the result of my quest to understand when and why its proud signature motto, “All The News That’s Fit to Print,” was distorted by abiding discomfort with Zionism and the restoration of Jewish national sovereignty.

Auerbach introduces his study by noting that 1896 was the year in which both the enterprising young Adolph Ochs bought the New York Times and Theodor Herzl published Der Judenstaat. Herzl’s first mention in the Times came a year later. “It identified him,” Auerbach writes, “as ‘originator of the Zionist scheme,’ which had been ‘so coldly received by those to whose attention it has been called in this country.’” Left unmentioned was that among those who had given the Zionist idea chilly reception were the Times’s new publisher, Adolph Ochs, and his father-in-law, America’s leading Reform rabbi, Isaac Mayer Wise.

Auerbach

finds the genesis of the paper’s consistently critical stance toward Zionism

and Israel in Ochs’s “fervent determination that the Times would never

appear to be a ‘Jewish’ newspaper” and that his successors in the

Ochs-Sulzberger family would never let the specter of dual loyalty alight upon

them. Fiercely loyal Reform Jews (and eventually Episcopalians of Jewish

descent), they were vehemently opposed to, if not appalled by, the notion that

Jews were anything but members of a religious faith. As a result, the family

opposed from the outset any expression of the idea that Jews should “return” to

Zion and

expressions of Jewish particularism in general.

One could understand this attitude during the first half of the 20th century, when the idea of a Jewish state could have been seen as far-fetched. But it persisted far longer, until well after the establishment of the state. In 1986, almost a century after it had first dismissed Herzl’s idea, the New York Times still refrained from calling Israel a “Jewish state.” Even its leading correspondents were baffled by this anachronism. In a private letter to his editor, David Shipler, who had covered Israel for the paper in the 1980s, observed, “[H]ow bizarre it must seem to anyone sitting in, and reporting from, Israel . . . to find that Israel cannot be described as a Jewish state in his newspaper. . . . [I]t is a Jewish state. . . . Saying so is not an endorsement and is not a criticism, but merely a statement of reality.”

When Shipler asked for the reasons behind this strange policy, the best he could elicit from the editors was a repeated rumor “that after ’48 the Publisher had certain attitudes about Israel.” For Auerbach, there was no better indication of the paper’s “enduring Jewish problem.” There didn’t have to be an explicit “house style” ruling on the “Jewish state” issue; the editors knew it instinctively from their years at the paper. And, as Auerbach shows, the attitudes and anxieties underlying this policy extend back a full half-century before 1948.

Auerbach provides readers with so many examples of outright imbalance on the part of the paper that a reader might be justified in thinking that he is just cutting and pasting previous paragraphs with a change of locale, date, and reporter. Contrast, for example, the way Israeli victims and Palestinian perpetrators were treated by the paper in the following seven instances between 1996 and 2016.

In 1996 Hamas bombed a bus in downtown Jerusalem, killing 19 people. On the next day, 13 Israelis were killed and a hundred people—many of them children—were injured in a bombing in a Tel Aviv mall, which “sent victims sailing through the air.” The Times’s coverage focused on the political impact of these events. When there were protests in Jerusalem in the neighborhood where many of the victims lived, no reporter interviewed either the victims’ families or the residents.

In 2002, 13 Israeli soldiers were ambushed and killed in Jenin while engaged in house-to-house fighting because the IDF did not want to drop bombs that would kill innocent civilians. At the same time, eight Israelis were killed in a suicide bus bombing. In reporting on these events, the paper focused on reports of an Israeli massacre of a hundred Palestinian civilians. The reports were false.

In 2002, when an Israeli Arab set off a bomb killing six Israelis at a bus stop, Times correspondent Joel Greenberg visited his village and covered his funeral. There was no coverage of the Israeli victims.

On Erev Yom Kippur 2002, a Palestinian woman blew herself up in a Haifa restaurant, killing 19 Israelis. London bureau chief John Burns devoted a six-column report to his journey to Jenin to visit her parents, describing their “careworn but proud gentility” and “elaborate courtesy.” He ignored the Israeli victims. When criticized, he said that he wished to illustrate the “spiral of mutual dehumanization and violence,” seemingly oblivious to the fact that he had dehumanized the 19 Israeli victims by ignoring them.

In 2013, when a Palestinian teenager fatally stabbed an Israeli soldier who was asleep on a bus, the paper gave prominent display to the picture of the assailant’s grieving mother. This time the newspaper acknowledged that this was a poor choice. As Auerbach tartly and correctly notes, it was a “choice that exposed Times preoccupation with Palestinian victimization—even when Israelis were the victims.”

In 2015 Palestinian president Abbas claimed that a 13-year-old boy had been “executed on a Jerusalem street.” An Israeli hospital released a photo of him recovering while being fed by an Israeli nurse. Times reporter Isabel Kershner described this as evidence of “conflicting versions of reality.”

In 2016, when an Israeli 13-year-old was stabbed 18 times in her bedroom, reporters focused on the murderer, not the victim, and speculated that he might have been trying to “emulate a young woman from his hometown” who a few days earlier had driven her car into a bus stop.

These are by no means the only instances of bias Auerbach documents during this 20-year period. Although his book is essentially a trawl through the archives and not a formal content analysis, his extensive documentation of comparable bias in the other hundred years of the Times’s coverage makes it clear that it is an institutional pattern.

As the Times’s own editorial board has recently admitted, its problem acknowledging Jewish victimhood has not been restricted to Israelis. In his discussion of the paper’s coverage during the era when “anti-Semitism rose up and bathed the world in blood,” Auerbach provides three stunning erasures of the fact that the victims in the stories were Jews. The paper described the SS St. Louis as the “saddest ship afloat” but failed to identify the passengers as Jews. When a boat was stranded in the Danube with five hundred Jewish refugees aboard, the passengers were described as “helpless and terrified human . . . flotsam on the authoritarian sea of death,” but what kind of humans and why, precisely, they were terrified were left unmentioned. The same thing happened when the Struma, a boat stranded off the coast of Turkey, sank with over seven hundred Jewish passengers aboard in 1942.

Nonetheless, it should be noted that there were scores of articles in the paper that did call attention to the specific suffering of Jews. Kristallnacht was given front-page coverage. Reports on the mass killing of Jews were repeatedly published. While there were tremendous gaps in the paper’s coverage of the Holocaust, Auerbach’s decision to present these examples as emblematic somewhat undercuts his case.

Not only were Israeli victims repeatedly ignored, but the Times’s reporters and columnists seem to consistently bend over backward to explain away Palestinian wrongs and find moderation among the perpetrators. Even after Hamas claimed responsibility for the murder of 58 Israelis in eight days in the early months of 1996, Jerusalem bureau chief Serge Schmemann admonished Israelis for their “constant and total” war against terrorism and wondered whether Hamas was really an “irreconcilable enemy of peace.” After all, he noted, terrorism was only “a small fraction of its activity,” and it had engaged in social work and politics. Subsequent events would prove him spectacularly wrong.

At the same time that the paper was reporting on how two Israeli reserve soldiers had blundered into Ramallah, where they were captured, murdered, and decapitated, Anthony Lewis praised Palestinians for having learned from Nelson Mandela that “patience and negotiation were the best way to vindicate their rights.” In 2006, Thomas Friedman was still predicting that Hamas would “evolve” away from its terrorist activities. It has not. For these columnists, Auerbach contends, “Israel was the provocation for which terrorism was the predictable response.”

Sometimes Auerbach goes too far, criticizing the paper for publishing views that, while critical of government policy, are held by many Israelis. He is annoyed when the paper noted that many Soviet Jews who immigrated in the 1990s had “little if any Jewish identity.” Yet that was precisely the case. He is angered by the paper’s concerns about the power of the ultrareligious parties. But many Israelis, on the right and the left, both religious and secular, are deeply distressed by how those parties have used their political clout to thwart the will of the majority on numerous issues. Indeed, it is a key issue in the present elections. Auerbach argues that the paper pays disproportionate attention to the “Who is a Jew” issue even though “only a minuscule number of American Jews would be affected” by the legislation. In doing so, he ignores the fact that the debate speaks not only to the relationship between American Jews and the Jewish state but to American Jews’ identity and the legitimacy of their rabbinic leaders.

He is disturbed that the paper published a column by then–Jerusalem Report editor David Horovitz, currently the editor of the Times of Israel, one of the more important sources for news of Israel, that describes Israelis’ fears that “unless Israel can separate from the 3.5 million Palestinians, it cannot remain democratic and predominantly Jewish.” But that is precisely what many Israelis fear. He criticizes columnists and reporters for relying on critics such as Rabbi David Hartman, David Grossman, Amos Oz, a “disgruntled Shin Bet chief,” and many other prominent Israelis. Oz, the disgruntled spymaster, and these others might have opinions with which Auerbach disagrees, and the Times has certainly tilted left in its choices, but to dismiss them as unworthy sources and contributors unnecessarily weakens his critique, which, overall, is devastating.

Print to Fit was written well before the

Jew-dog cartoon scandal, but it does answer the question about it with which

this review began: How could such an image make it to the pages of an edition

of the New York Times? If the editor who chose the cartoon had relied

solely on what the Times has seen “fit to print”for an

understanding of the Israel-

Palestinian issue, then it should not have been much of a surprise.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Athens or Sparta? A Response

Patrick Tyler accuses Benny Morris of being unfair in his attacks on Fortress Israel.

Forget Remembering

Rutu Modan’s graphic novel The Property explores the uneasy coexistence of love and death.

Pro-Creation

Economist Bryan Caplan thinks parents “overcharge” themselves when it comes to investing in their children. Glückel of Hameln knew better.

Hasidism, Jung, and the Jewish Spiritual Crisis

Carl Jung said that the great “the Hasidic Rabbi whom they called the Great Maggid” anticipated his entire psychology. He learned that from his Jewish student Erich Neumann, whose Roots of Jewish Consciousness was never published until now.

David Z

In defense of Auerbach, the NYT prints these articles discussing Jewish identity at the very least in much greater number than articles discussing Chinese, Indian, Iranian, etc. identity. The fixation does seem to be to spotlight Israel's troubles. Finally, they are actually reporting fact. But still the facts they choose to report are troubling...

Howard S.

Historically, the worst anti-Semites have often been Jewish converts to Christianity, or others who are attempting to leave their Jewish ancestry aside. The Sulzberger family, practicing Christians at this point, are still trying to prove that they have left their Jewish background behind and can be as anti-Semitic as their fellow Christians.