Bellow, Broadway Billy, and American Jewry

In late May of 1988, Saul Bellow and his soon-to-be-wife Janis Freedman went to a dinner party in Vermont. Bellow, Zachary Leader tells us in the forthcoming second volume of his excellent biography, had been brooding about Jewish history. At the dinner, he asked his friends whether they thought Jews should feel shame over the Holocaust. Was there “a particular disgrace in being victimized?” During the discussion, his host, Herb Hillman, told a story about a fellow chemist he knew who had been saved by the famous “Broadway” Billy Rose. Rose had somehow helped get the friend out of an Italian prison and then out of Europe entirely in 1939, but, in the decades that followed, Rose had never consented to meet the man he had saved. Within days, Bellow was working on the story that would become The Bellarosa Connection.

Bellow’s extraordinary novella seems to have been the inspiration for Mark Cohen’s new biography, Not Bad for Delancey Street: The Rise of Billy Rose, America’s Great Jewish Impresario. And, in truth, I picked Cohen’s book up as much to rethink Bellow’s morally rigorous artistry as to learn about 20th-century show business.

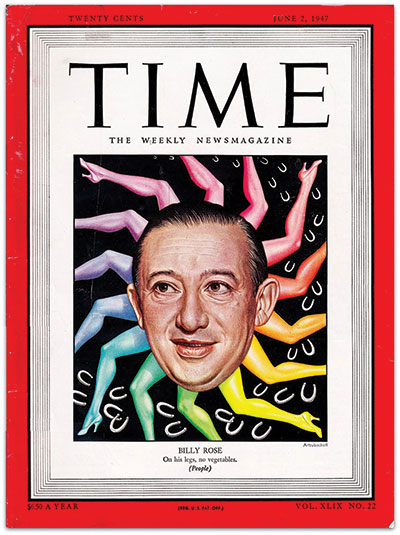

For a quarter of a century Billy Rose was America’s master showman. While Hitler was putting on mass rallies to consolidate power in Germany, Rose opened nightclubs, produced musicals, and organized extravaganzas to lift Americans from the woes of the Great Depression: His Casa Mañana Revue at the 1936 Texas Centennial featured the world’s largest revolving stage, stripper Sally Rand, and lots of celebrities; Billy Rose’s Aquacade was a swim, song, and dance show with Eleanor Holm and Johnny Weissmuller at the 1937 Great Lakes Exposition and then the 1939 New York World’s Fair. For Rose, it was always about amassing personal fame and fortune, including social influence and trophy wives—he divorced Fanny Brice to marry Holm. But the contrast with Hitler is not entirely gratuitous: The Jewish boy from the Lower East Side paid attention to the news from Europe and applied some of his talents to fighting back even as he fought to get ahead.

Born in New York City on the second day of Rosh Hashanah 1899, Billy (registered as Samuel Wolf Rosenberg) was the firstborn and only son of a mismatched immigrant couple that soon separated. Mark Cohen suggests the boy got his entrepreneurial flair and his sense of himself as a Jew from his mother Fannie, who started a short-lived company to sell a laundry detergent she called Washquick and time after time raised money for fellow Russian Jews to get to America. His lifelong claustrophobia also dated from childhood, when bullies threatened to dig a hole and “bury the little shrimp,” but he turned into one of those who compensated for small stature with gargantuan ambition.

Improbably, his first triumph was as a champion of the Gregg Shorthand method, which he learned in high school. This led him to a job at the War Industries Board (WIB) working for the American Jewish financier Bernard Baruch, and even earned him a meeting with President Wilson, who practiced the Pitman method of shorthand but wasn’t as fast as Billy. As Rose virtually floated out of the White House and back to the WIB offices, he thought, “Not bad for Delancey Street.”

By the late 1920s, he was collaborating on the lyrics of popular songs like “Me and My Shadow” and “More than You Know,” though his talent was always more in promotion and getting a piece of the action. Nonetheless, his intelligence and taste, later manifested in an excellent art collection, were often underestimated at least in part because he was a tough guy and acted the part. He fashioned and managed the details of his every venture, knowing that the tastes of an open, democratic culture could be satisfied equally through high patriotism and low fantasies of scantily clad women. When a young Gene Kelly choreographed a football-themed dance number, Cohen tells us, “Rose nixed it, saying, ‘They don’t come to the Diamond Horseshoe to see a fucking ballet.’” He wasn’t so much a cynic as a showman who was genuinely eager to satisfy his customers.

Billy’s rise coincided with the most critical period in modern Jewish history, when anti-Semitism in Europe called for massive response from American Jews. Although he was less than admirable in many ways, his refreshingly active response to the crisis compares favorably with that of the American Jewish leadership. Cohen describes but does not explore the uniqueness of Rose’s association with all the otherwise contending sectors of the American Jewish community—the Left, the Right, and the establishment, in that order. In 1936, the Soviet Union temporarily suspended its war on liberal America and used the Popular Front, which Cohen describes as a “loose conglomeration” of antifascist groups, to exploit the concerns of Jews like Rose. We are not told whether Billy—himself a superb manipulator—realized that he was being played in funding Communist-inspired antifascist productions.

The Jewish American romance with the Soviet Union was suspended during the years of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, 1939–1941, and it was then that Rose was drawn to Peter Bergson, alias Hillel Kook (nephew of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, chief rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine). Bergson was raising support in America for a Jewish army in Palestine that would join the fight against Hitler and for a Jewish state. Opposed by the very cautious Jewish leadership, Bergson’s tiny group gained the backing of writer Ben Hecht, and through him of Rose, who was attracted by their bold Zionist vision. Although he worked with Moss Hart, Ernst Lubitsch, Kurt Weill, and others, Rose deserves much of the credit for filling Madison Square Garden to the rafters for the 1943 pageant of protest and resistance We Will Never Die, an extravaganza that called for action on behalf of Europe’s Jews, not pity.

Mark Cohen has helpfully tracked down the details of the story Herb Hillman told Bellow. Kurt Schwarz, an Austrian Jew who was arrested in Italy after seeking refuge there, did what thousands of other desperate refugees did—he wrote to a prominent American Jew pleading for help. Rose responded. In Bellow’s dramatization, the rescue is a bit more mysterious. As the Schwarz figure (Fonstein) describes it:

“I was in a cell by myself. Those years, every jail in Europe was full, I guess. Then one day, a stranger showed up and talked to me through the grille. . . . I went over and said, ‘Ciano?’ He shook one finger back and forth and said, ‘Billy Rose.’ I had no idea what he meant. Was it one word or two? A man or a woman? The message from the Italianer was: ‘Tomorrow night, same time, your door will be open. Go out in the corridor. Keep turning left. And nobody will stop you. A person will be waiting in a car, and he’ll take you to the train for Genoa.’”

All Fonstein has is the mysterious name “Bellarosa,” as pronounced by the Italian intermediary. This little flourish would seem to be Bellow’s conceit, but the rest is the same: The refugee receives passage to New York and then is, to his disappointment, sent to Cuba. While the surviving correspondence between Schwarz and Rose confirms these details, it also provokes questions: Was Billy running a covert rescue operation as Schwarz believed, or did he undertake just this single case? Why, having originally offered Schwarz a job in bringing him to New York, did Rose refrain from meeting him and ship him off to Cuba instead? And, most fundamentally, why did he refuse to acknowledge his good deed?

In The Bellarosa Connection, Fonstein and his formidable wife Sorella try in vain to get the savior to acknowledge the person he saved. When I recently discussed Bellow’s story in a seminar, several students didn’t see the problem. Wasn’t saving Fonstein’s life enough? Not according to Bellow. His unnamed narrator is a septuagenarian (as was Bellow in 1989), the retired founder of the Philadelphia-based Mnemosyne Institute, who made memory into an international business—a technical skill (like Billy Rose’s mastery of shorthand) that enhances efficiency without affecting substance. He teaches memory but would rather put out of his mind his long-standing neglect of the Fonsteins, to whom he is somewhat distantly related.

Billy Rose and the narrator are thus both specialists in retrieval—people and memories—who end up discarding what they had saved. The Billy Rose story frames the narrator’s own moral accounting as a Jew whose success is summed up by his antebellum Philadelphia house, which his late Gentile wife furnished with 18th-century furniture. While Fonstein was working his way up, the American-born narrator, a generation ahead in acculturation, was becoming even more detached from their shared European Jewish origins. Ask not for whom the Liberty Bell tolls—it tolls for thee.

The dramatic center of The Bellarosa Connection is a scene set in the late 1950s at the heart of Jewish history, in Jerusalem. The narrator has come to see about setting up a branch of his Mnemosyne Institute and Billy Rose to set up his famous sculpture garden next to the Israel Museum. The Fonsteins are there too, but that’s no coincidence. Sorella had deliberately arranged their visit to coincide with Billy’s so that she could force him into meeting her husband. She is determined that Harry be respected as more than simply an object of rescue. To that end, she has obtained from Rose’s former assistant—a woman as shrewd as herself—an incriminating journal which records Billy’s shady behavior. Sorella threatens to make the document public if Billy continues to refuse to meet the man he saved.

The antagonists in this confrontation in the King David Hotel are, to say the least, vivid: American-born Sorella is so outsized, “she made you look twice at a doorway.” Such Rabelaisian remarks are bound to discomfit those trolling for signs of misogyny, but Bellow, whose characters’ bodies often express their spirit, has something else in mind:

Maybe Sorella was trying to incorporate in fatty tissue some portion of what [her husband] had lost—members of his family. There’s no telling what she might have been up to. . . . Exquisite singers can make you forget what hillocks of suet their backsides are. Besides, Sorella did dead sober what delirious sopranos put over on us in a state of false Wagnerian intoxication.

She is also as witty as the narrator. She describes the fuss Billy Rose made on his arrival over his lost luggage: “If he had kept on hollering, I could see Ben-Gurion himself sitting down at the sewing machine to make him a suit.”

As for Billy, he was “about the size of Peter Lorre: But oh! he was American. There was a penny-arcade jingle about Billy, the popping of shooting galleries, the rattling of pinballs, the weak human cry of the Times Square geckos, the lizard gaze of side-show freaks.” Sorella finally manages to confront him in his hotel suite:

“Mr. Rose, you haven’t called me by my name,” she said to him. “You read my letter, didn’t you? I’m Mrs. Fonstein. Does that ring a bell?”

“And why should it . . . ? He said, refusing recognition.

“I married Fonstein.”

“And my neck size is fourteen. So what?”

“The man you saved in Rome—one of them. He wrote so many letters. I can’t believe you don’t remember.”

“Remember, forget—what’s the difference to me?”

Their confrontation ends with Sorella heaving the blackmail evidence out the window—and effectively out of the story—because she realizes the desired communion with Billy is not even desirable.

After telling him this story, Sorella asks the narrator, “How do you see the whole Billy business?” And then, dissatisfied with his answer, supplies her own:

But if you want my basic view, here it is: The Jews could survive everything that Europe threw at them. I mean the lucky remnant. But now comes the next test—America. Can they hold their ground, or will the U.S.A. be too much for them?

This “basic view” of Sorella’s is as close to a thesis statement as Bellow ever comes in his fiction.

The final third of the novella is set in the late 1980s, when the narrator is suddenly reminded of the Fonsteins by a call from Jerusalem looking for Harry on behalf of an aged, unbalanced survivor with the same surname who needs help. The book has come full cycle from the rescue of Harry to the call for Harry to rescue another Fonstein, another Jew. Far from resenting the appeal to him as an intermediary, our narrator welcomes the chance to reconnect with Harry and Sorella. He even toys with the idea of joining them in retirement. But he can’t track them down. Unlike our memory man, Fonstein’s other relations do not even regret having lost touch with him. The closest relative, a lawyer with impeccable phone manners, makes the narrator realize that in America, “One could assimilate now without converting. You didn’t have to choose between Jehovah and Jesus.” That Billy Rose should once have responded to a Jewish stranger’s call for help has come to seem as improbable as the parting of the Red Sea.

Worse than this indifference to the Fonsteins is what our narrator learns when he at last gets through to their home number in New Jersey and reaches someone who identifies himself as the “house-sitter,” a friend of their only son, Gilbert. Toying with the caller, the friend unhurriedly reveals that Gilbert, a mathematical genius, had applied his talents to blackjack, and that, on their way to Atlantic City to rescue him from some trouble at a casino, the parents were killed on the Jersey Turnpike.

From the friend’s manner and some dropped details about a bandana and crumbs in his beard, the narrator conjures up the person behind the voice.

I formed an image of a heavy young man—a thick head of hair, a beer paunch, a T-shirt with a logo or slogan. Act Up was now a popular one. I pictured a representative member of the youth population . . . Rough boots, stone-washed jeans, bristly cheeks—something like Leadville or Silverado miners of the last century, except that these young people were not laboring, never would labor with picks. It must have diverted him to chat me up. An old gent in Philadelphia, moderately famous and worth lots of money. He couldn’t have imagined the mansion, the splendid room where I sat holding the French phone, expensively rewired, an instrument once the property of a descendant of the Merovingian nobility. (I wouldn’t give up on the Baron Charlus.)

This is the book’s third mention of this baron (of whom more in a moment), and by this point Bellow seems to have stopped worrying about whether we can hear his voice behind the narrator’s. To the caller’s question whether Gilbert takes any interest in his Jewish background—“for instance, in his father’s history”—the friend’s slight hesitation is enough to suggest that he is Jewish himself, though he doesn’t care much about it. “The only life he cared to lead,” the Bellovian narrator muses, “was that of an American. So hugely absorbing, that. So absorbing that one existence was too little for it. It could drink up a hundred existences, if you had them to offer, and reach out for more.” The narrator keeps hoping to make a connection with the young man on the other end of the line (the way Sorella presses Billy Rose to meet with her husband), there being so little else left for him to hang on to. The house-sitter signs off with “your timing was off. But don’t pine too much.”

In this concluding section of the book we feel the full weight of years. Our aging narrator forgets words and phrases he has known all his life: “Way down upon the River.” His search for the Fonsteins is part of a larger attempt to recover things that are slipping away. This is Bellow’s own compressed and idiosyncratically American Remembrance of Things Past. Every time the narrator makes a phone call using the art nouveau porcelain instrument that his wife had installed, he thinks not of her, nor of Proust, but of Proust’s most perverse character, the thoroughly anti-Semitic Baron de Charlus, as corrupt as he is pathetic. Why does he associate his condition with so debauched a character? Why is he so hard on himself? One night he dreams that he is in a deep hole and cannot climb out despite his most strenuous effort. No need to interpret: He thinks he has dug his own grave.

In the late 1980s, I had dinner with Saul Bellow, his wife Janis, and my son Jacob at the Café des Artistes and finally got up the nerve to ask Saul a question that had troubled me for years. How could he have ignored what was happening to the Jews in Europe and Palestine in the late 1930s and most of the 1940s? I said I was asking as well about his whole cohort of Jewish intellectuals, who, in truth, had reacted nothing like Billy Rose, let alone Ben Hecht. Saul said, “America was not a country to us. It was the world.” I might have wished for more, but this book, written a few years later, amplifies his answer. The only life Gilbert’s friend cared to live was that of an American. “So hugely absorbing, that. So absorbing that one existence was too little for it . . .” Sorella’s rhetorical question has been answered. The U.S.A. has proved too much for the Jews.

However, the old Jew is not yet quite done. It seems he is still standing after all not in the grave of his nightmare but before the Gates of Judgment. Wondering what he could say to make an impression on the kid at the other end of the line he recalls the first words of the prayer recited in memory of the dead, “Yiskor Elohim,” which asks God Himself to remember those who must pass away. This first mention of God, this first use of Hebrew, come almost but not quite too late for him, though they are unlikely to sway the fully absorbed American hipster. As for the Bellovian narrator, the best he can do is to record “everything I could remember of the Bellarosa Connection, and set it all down with a Mnemosyne flourish.”

Mark Cohen believes that his biography shares the upbeat judgment of Billy Rose that is implicit in the title of Bellow’s book. “Billy Rose, with all his flaws and pettiness and occasional brutality, is . . . bella rosa: ‘beautiful rose.’”

[He] met the challenges of American Jewish life on both fronts with all the intensity and joy and enthusiasm and caginess and wariness and toughness that his dual inheritances encouraged and required. As a savvy oddsmaker, Rose seems to have decided that the Jewish American project was a stacked deck. America is a huge country and the Jews are few, and even with all the ambition in the world, certain Jewish heights could be achieved only in Israel. Rose went there to scale those heights. But he came back, and he brought some Jewish artifacts with him to live, for the little time he had left, the mixed and rich and complex and confusing and thrilling experience of the American Jew. It is an identity he helped pioneer and invent, and it still can serve as a model for vital American citizenship.

This is a fine summation of Cohen’s rightful claim of Broadway Billy Rose for the Jews, and a sunny answer to Sorella’s question. He is not mistaken, either, in sensing that Bellow found some virtue in both the man and his type. Tough guys who could get things done like Billy often complement the introspective narrators of Bellow’s fiction, and he appreciated Billy’s Jewish fellow feeling and actions. “Billy,” he wrote, “was as spattered as a Jackson Pollock painting, and among the main trickles was his Jewishness.”

Yet for Bellow, Rose’s refusal to meet with the man he had saved is just as important. It is an augury of forgetting on the part of a people once renowned for its memory. Bellow actually saw Billy Rose in Jerusalem around the time that he set the Sorella-Billy showdown, where his own regret for having failed to act on behalf of the Jews would have been most acute. This may be why the Hillman story struck such a chord and why the Mnemonic narrator uses it to atone. The Bellow–Rose connection asks to be remembered.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

King James: The Harold Bloom Version

There may be a thousand facets to the Torah, but does Harold Bloom simply misunderstand the King James Bible?

Learning from History

Jonathan Sarna looks back at a time when both Reform and Orthodox Judaism in America seemed imperiled.

Harlem on His Mind

Many Harlem churches that were once synagogues have been torn down to make way for apartment buildings with all the latest amenities.

Anti-Israelism

It's a new prejudice, not just the old story in a new guise.

notrye

Perhaps the most important lesson to take away from the Jewish response to the Holocaust is the closing remark of "Yizkor Elokim". G-D will indeed remember the indifference of the American Jewish community, especially the Jewish establishment i.e. . Stephen Wise, with very few exceptions.

That generation will have to stand before the "Kissei Hakovod", the Heavenly Court, and be forced to say "ASHAMNU, BAGADNU, YATZNU RA, and most importantly TAINU V'TITANU".

This was perhaps the greatest moment in history of "hester Panim" G-D's veiling His Presence from humanity(?) and especially the American Jewish establishment.