Kashrut and Kugel: Franz Rosenzweig’s “The Builders”

In 1966, Commentary Magazine sponsored a symposium, “The Condition of Jewish Belief,” consisting of statements of Jewish faith by 38 American rabbis and thinkers. In his introduction, Milton Himmelfarb wrote that “15 to 17, mostly youngish,” of the 27 non-Orthodox rabbis who participated in the symposium were “disciples of Franz Rosenzweig.” Thus, Himmelfarb dramatically concluded, “The single greatest influence on the religious thought of North American Jewry . . . is a German Jew—a layman, not a rabbi—who died before Hitler took power and who came to Judaism from the very portals of the Church,” which, as a young man, Rosenzweig had famously considered joining. Upon rereading the Commentary symposium two things become clear. First, the non-Orthodox rabbis in question were searching for a meaningful non-Orthodox conception of revealed law; second, they found it, not in Rosenzweig’s profound but difficult, almost hermetic, magnum opus, The Star of Redemption, but rather in his short essay “The Builders” (Die Bauleute).

“The Builders” was written in 1923, two years after the publication of The Star, as an open letter addressed to Martin Buber. In it Rosenzweig responded to his friend, erstwhile mentor, and future collaborator Buber’s essay “Herut: On Youth and Religion.” The epigram of Buber’s essay was from a famous Mishnah in Pirke Avot (Chapters of the Fathers): “God’s writing engraved on the tablets”—read not harut (engraved) but herut (freedom). As Buber wrote to Rosenzweig in the exchange of letters that followed “The Builders,” “I do not believe that revelation is ever a formulation of law. It is only through man in his self-contradiction that revelation becomes legislation.” It was to this problem, whether and in what way one might be bound by Jewish law, that Rosenzweig addressed himself.

Perhaps the key passage was Rosenzweig’s passionate affirmation concerning the entire realm of Jewish practice:

Whatever can and must be done is not yet deed, whatever can and must be commanded is not yet commandment. Law [Gesetz] must again become commandment [Gebot], which seeks to be transformed into deed at the very moment it is heard.

That is, for Rosenzweig, the individual in performing a particular law may come via that performance to hear God’s commanding voice, to sense His commanding Presence—though one can never tell in advance whether this might or might not happen. But the possibility always exists that the law, the dry, objective statute on the books, the “do-able” to use Rosenzweig’s term, can become “deed,” personal commandment, by becoming transparent, as it were, and serve as a bridge between man and God. For Buber, in contrast, one should fulfill a particular commandment only if one is convinced beforehand that the law is addressed to him: “I may not just accept the ‘statutes and judgments,’ but must ask of each one, and ask again and again: Has that been said to me, rightly to me?”As Rosenzweig saw, such an approach would preclude any real sense of Jewish law. It was of no help in answering the crucial question: “What shall we do?”

Yet, despite the importance and influence of “The Builders,” in the great proliferation of new editions, translations, and studies of Rosenzweig in recent decades, the essay has been rather neglected. There has, first of all, been no new English translation of “The Builders,” despite the fact that Nahum Glatzer’s translation suffers from imprecisions and, even more troubling, perplexing abridgements of Rosenzweig’s text.

The time has come, then, to reread Rosenzweig’s classic essay. As earlier scholars have done, I too will focus on Rosenzweig’s discussion of the path through the realm of practice, of the “do-able,” leading up to that climactic moment when law becomes commandment.

However, I believe we are now better positioned to appreciate some of the essay’s boldest and most incisive theses thanks to recent scholarship on minhag (custom) and its place in Jewish life in the modern and medieval periods. Therefore, while the approach of most earlier commentators has been to focus on the relationship between law and revelation in “The Builders,” I will focus on Rosenzweig’s discussion of the relationship between law and minhag. This will serve to illustrate what I have always found to be the remarkable nature of Rosenzweig’s intuitions and perhaps even bring us to the very heart of his view regarding law, revelation, and the individual’s relationship to God.

Two of the most influential essays in modern Jewish studies written in the past 20 years are Haym Soloveitchik’s “Rupture and Reconstruction: The Transformation of Contemporary Orthodoxy” and Menachem Friedman’s “The Lost Kiddush Cup: Changes in Ashkenazic Haredi Culture.” Both Soloveitchik and Friedman analyze the transformation of contemporary Orthodoxy from a community in which practice is learned through imitation of one’s parents and peers (what Soloveitchik calls a “mimetic community”) to a text-based community, where practice is primarily determined by canonical legal texts.

Here Friedman’s by now famous example of the “lost” kiddush cup of the great early-20th-century rabbinic leader Rabbi Israel Meir Kagan, known as the Hafetz Hayim, is particularly apposite. In the 1940s, the eminent Israeli haredi rabbinic authority Rabbi Abraham Karelitz, known as the Hazon Ish, re-examined the relevant legal texts and arrived at the revolutionary conclusion that the amount of wine required in order to properly fulfill the commandment of “saying kiddush” was much greater than previously thought. This meant that most standard kiddush cups could not be used. What is striking is that this theoretical legal conclusion, which, in truth, had already been suggested by some earlier authorities, was adopted in practice by the haredi community, and even by some in the modern Orthodox community, in direct contradiction to the customary practice. The story goes that the grandchildren of the Hafetz Hayim, the author of the authoritative Mishnah Berurah and generally considered to be the greatest posek (halakhic decisor) of the early 20th century, refused to make kiddush over their own grandfather’s kiddush cup, because it wasn’t large enough to meet the standards of the Hazon Ish.

The question raised by both Soloveitchik and Friedman is how to account for such transformations. Both begin with the work of the great historian Jacob Katz, who often distinguished between pre-modern traditional Jewish societies and Orthodoxy in the modern era. Traditional societies, Katz argued, took their values and conduct as a given and acted unself-consciously, unaware that life could be lived differently. The modern era, with its massive challenges to tradition, led to the transformation of such traditional Jewish societies into Orthodox ones. In modern Orthodox societies, religion is less the product of social custom than of conscious reflective behavior, and, indeed, ideological systems are constructed to defend the rightness and necessity of that behavior. This was the first step away from the mimetic community based on social and communal custom. It is striking how much of Katz’s analysis was anticipated by Rosenzweig. Rosenzweig does not use the term “traditional society,” but writes of those “living without question,” and again of “a Jewish consciousness that does not question and is not questioned,” as opposed to the Western Orthodoxy of Samson R. Hirsch and Isaac Breuer, which, precisely under the pressures of questioning, constructed impressive, but, in Rosenzweig’s view, narrow, rigid, and unlovely ideological defenses of the authority of the Law.

If Soloveitchik and Friedman concur on the reason for the first step away from the mimetic community, they differ with respect to the second step, the move to a text-based community. Friedman sees the main catalyst as being the proliferation of yeshivas, advanced academies for talmudic study, which, in their modern form, are deliberately isolated from and independent of surrounding communities. Soloveitchik, more convincingly to my mind, considers the main catalyst to be the acculturation of the Eastern European Orthodox community in Israel and particularly North America, where observant Jews, while remaining strictly observant—indeed, often becoming more observant than their parents—have nonetheless absorbed the rhythms, values, and lifestyle of middle-class culture. Judaism has thus ceased being a total culture, and has instead become an enclave. That is—this is my example—from a cultural standpoint, contemporary Orthodox Jews are suburbanites or Manhattanites, who are also shomer mitzvot, observers of the commandments. By contrast—to return to Soloveitchik—what a mimetic society hands down from one generation to the next is a total culture. Once this was lost, Jewish law and practice could no longer be entrusted to communally based modes of transmission; they had to be anchored more securely and exclusively in textual tradition.

The congruence of Soloveitchik’s analysis with Rosenzweig’s discussion is remarkable, though Rosenzweig, of course, aimed to prescribe as well as describe. In seeking the path through the “do-able,” the totality of Jewish practice, leading to the deed, Rosenzweig attacked the modern differentiation made by Western European Orthodoxy of his day between the inner realm of Judaism, ruled by law, and the outer, “non-Jewish” realm, which is the sphere of the permissible. Rather, he argued, the border should be erased, and the outer sphere of the permissible should be Judaized by being governed by minhag and the underlying intent of the law. “For those who eat Jewish dishes,” he wrote, “all the traditional customs of the menu as handed down from mother to daughter must be as irreplaceable as the separation of meat and milk.”

To be sure, there is a fundamental difference between the contrast drawn by Rosenzweig and that drawn by Soloveitchik and Friedman. For Soloveitchik and Friedman, the contrast is between a mimetic society based on customary practice and one based on texts. For Rosenzweig it is between law and minhag. But the connection between the two sets of contrasting terms should also be clear. In a traditional, mimetic society, practice is handed down as a whole from one generation to the next, and the distinction between law (biblical and rabbinic) and minhag is glossed over. In a text-based society, the differences between the legal status of the practices prescribed and analyzed in those texts and minhag come to the fore. We might say that Rosenzweig’s goal was, in Soloveitchik’s terms, to reverse the process that had led to rupture and reconstruct this lost mimetic community.

Rosenzweig, however, wished to go further. He aspired not only to resurrect Jewish custom and break down the barriers between the inner and outer realms, but to replace what he deemed to be the traditional, somewhat dismissive attitude toward minhagim (“it’s only a minhag”) with one that would give them the same status as law. Only in this way could the outer realm be truly Judaized. To repeat: The traditional dishes handed down from mother to daughter—minhag—should be as irreplaceable as the legal requirement of separation of meat and milk—halakha. To paraphrase: Kugel is as important as kashrut.

This equation of kashrut and kugel may seem to be—perhaps is—shocking, at least from an Orthodox point of view. What has emerged, however, from recent Jewish scholarship, particularly that of the late Professor Yisrael Ta-Shma, is that Rosenzweig’s attitude toward minhag, though he didn’t know it, had a kind of precedent in the religious life of pre-modern Ashkenazic Jewry. First, just as for Rosenzweig the function of minhag was to ensure “that not one sphere of life is free from the Law,” so too the function of minhag for pre-modern Ashkenazic Jewry was, to quote Ta-Shma, “to guide the individual in all the details and forms of his every day activities.” Even more important, for traditional, pre-modern Ashkenazic Jewry, minhag—grounded as it was in the practice of the sacred community—was accorded the same status as law, in a manner similar to Rosenzweig. Indeed, at times it was accorded a superior status. For law, based on argument and analysis, could always be challenged, whereas the customary practices of one’s ancestors were inviolable.

What is the basis of this unexpected similarity between Franz Rosenzweig and the authorities of medieval Ashkenaz? I would suggest that it is grounded in the religious significance—in the case of Rosenzweig the metaphysical significance—that both attributed to the sheer fact of Jewish peoplehood. For Ashkenazic Jewry, the community is, by definition, a holy community. Consequently, its customs—even when they are not mandated by authoritative legal texts, indeed even when they are in tension with these texts—have overriding significance. For Rosenzweig, to quote Leo Strauss, “the truly central thought of Judaism is Israel’s chosenness,” and so for him as well it is not surprising that this chosen community’s customs, as well as its fundamental laws, provide access to God’s commanding voice.

To carry this analogy further, Ta-Shma has noted how the Spanish Kabbalists, under the influence of Ashkenazic Jewry, offered esoteric mystical explanations not only of biblical and rabbinic laws, but of minhagim. Similarly, in theological discussions of ritual, Rosenzweig treated law and custom as a package deal. Thus, in describing the cyclical rhythms of the Jewish year in Book III of The Star of Redemption, he tended not to distinguish between custom and law. For example, in his description of Sukkot he sets the post-talmudic holiday of Simchat Torah and the very late custom of reading the book of Kohelet (Ecclesiastes) on the festival alongside his discussion of such fundamental biblical commandments as sitting in a succah and taking the four species.

There are also important differences between the medieval Ashkenazic view of minhag and Rosenzweig’s, and these differences also shine light on Rosenzweig’s basic theological position. To anticipate: For Rosenzweig minhag is entirely positive, and this in two senses. First, the actual minhagim to which Rosenzweig refers are almost entirely positive in nature, consisting mostly of actions and rites to be performed; and second, and even more importantly, the religious meaning of minhag is entirely positive for Rosenzweig. By contrast, for medieval Ashkenazic Jewry minhag primarily consists of proscriptions and injunctions. Moreoever, even when the minhag takes the positive form of performing a certain rite, it may carry negative significance.

Let us look at Rosenzweig’s examples of minhag and at the relationship of each minhag to its corresponding law. We have already seen the example of kashrut and kugel. Another example, from a little later in the essay: The legal exclusion of the woman from the congregation is counterbalanced by her customary primary rank in the home, as evidenced by the minhag of her husband singing “Eishet Hayil” (A Woman of Valor) to her every Friday night. A final example: The prohibition of images, of the plastic representation of God, is counterbalanced by the poetic descriptions of God as found in countless religious songs and liturgical poems, the customary recitation of which are nonbinding.

As noted earlier, what is especially significant is that precisely these minhagim—the traditional dishes, the singing of “Eishet Hayil,” the recitation of religious songs and liturgical poems—endow the laws themselves—the separation of meat and milk, the exclusion of the woman from a minyan, the prohibition of images, all of which have a negative form—with positive significance. Rosenzweig even sees the exclusion of the woman from a minyan positively, as flowing from the “the masculine military-public nature of the community” (this phrase, perhaps not surprisingly, is missing from the English translation!)—complemented by the feminine character of the home as evidenced by the singing of “Eishet Hayil.” (The tendency to think of minhag as female and halakha as male is interesting but hardly unique to Rosenzweig.) Finally, the prohibition of images testifies to the uniqueness of the incomparable God, that same hidden God whose praises have been sung by generations of Jews.

For medieval Ashkenazic Jews, by contrast, the vast realm of minhag in areas of everyday life, such as forbidden foods, sexual laws, and laws of mourning, took the form of additional stringencies, as has been documented by Ta-Shma and others. Indeed, even positive minhagim took on a negative significance. Thus, a story is told about how once an individual, while leading the service in a pre-modern Ashkenazic community, recited one liturgical poem at a particular point in the service though it was the practice of that particular community to recite a different poem at that point. He died within 30 days. The moral of this and other similar stories of medieval Ashkenaz is clear: Don’t tamper with minhagim.

I have argued that Rosenzweig and medieval Ashkenazic Jewry both valued minhag so highly because of the extraordinary emphasis they both put on Jewish peoplehood. Why did they differ? Why did medieval Ashkenazic Jews regard minhag primarily as a source of negative prohibition whereas Rosenzweig ascribed to it an almost purely positive significance?

The world for the medieval Ashkenazic Jew was a very dangerous place teeming with evil, sin, demons, witches, black magic, malakhei havalah (destructive angels), sickness, death, and religious persecution. Maleficent forces lurked around every corner. Many minhagim thus had prophylactic functions, serving to ward off these dangerous and unpredictable forces. Indeed, God Himself appeared to medieval Ashkenazic Jews as a fearsome, inscrutable Deity. Witness the popularity of that strange text, the ethical will (tzavaah) of R. Yehudah he-Hasid with its many stringent injunctions: A man must not marry a woman who has the same name as his mother and, by the same token, a woman must not marry a man who has the same name as her father; one cannot build a new house made of stone in order to dwell in it, but can only buy one. Even if none of these actions were halakhically prohibited, they were, as subsequent rabbinic scholars argued, intrinsically unlucky or dangerous. In a worst-case scenario someone might end up dead—for, literally, God knows what reason—and “hamira sakanta mei-issura,” a dangerous act is more to be avoided than a prohibited one. Better safe than sorry.

For Rosenzweig this dangerous, unpredictable world has dropped away. One keeps the minhagim to the extent of one’s ability, as one keeps the laws to the extent of one’s ability, because in doing so the “do-able” might become deed. That is, the moment might come when in performing those minhagim and laws, Law (Gesetz) will become commandment (Gebot), and one will, through them, hear God’s commanding voice and sense His commanding Presence. Moreover, this God is, in Rosenzweig’s view, not fearsome, but rather—and here I am drawing upon the The Star of Redemption—the loving God of the Song of Songs. Evil, suffering, and the fear of God are virtually absent from The Star of Redemption. In this regard, Rosenzweig’s discussion of sin is particularly revealing. When the soul confesses its sin before God, at that very moment of confession it experiences itself as beloved:

It cleanses itself of sin in the presence of His love. At the very moment that shame withdraws from it and it surrenders itself in free confession directed toward the present, it is certain of God’s love.

Contrast this with the harsh penitential rites—lashes, bathing in ice, extended periods of fasting, and so on—that were first set forth by the Ashkenazic pietists, and common among all sectors of Ashkenazic Jewry into the modern period.

We are now in a position to understand the crucial and revealing difference between Rosenzweig’s view of minhag and that of his medieval Ashkenazic predecessors. Nahmanides in his famous Bible commentary, commenting on the verse “Remember the sabbath day and keep it holy,” states that the negative commandments correspond to and express the fear of God, while the positive commandments correspond to and express the love of God. For medieval Ashkenazic Jews the fear of God overwhelmed, though never entirely displaced, the love of God; whereas for Rosenzweig, as Jerome Gellman has recently noted, “there is no mysterium tremendum.” Since for Rosenzweig there is no fear of God, all of Jewish practice—the positive commandments, the negative commandments, the minhagim—expresses, at least potentially, the love of God.

Writing in 1960, the distinguished Israeli philosopher Hugo Bergmann remarked that:

Without wishing to diminish the importance of Rosenzweig’s great theological work, The Star of Redemption, we can say that The Builders is Rosenzweig’s most actual contribution to the burning questions of our Jewish lives.

This may well be true, and we are now in a position to fully appreciate the meaning of the essay’s title, which (like Buber’s “Herut”) can be understood only through the rabbinic epigraph that immediately follows it:

And all your children shall be learned of the Lord, and great shall be the peace of your children. Read not “children” (banayikh), but “builders” (bonayikh).

As Rosenzweig famously states at the essay’s end:

[T]his is just the very basis of our communal and individual life: the feeling of being our fathers’ children, our grandchildren’s ancestors. Therefore we may rightly expect to find ourselves again, at some time, somehow, in our fathers’ every word and deed; and also that our own words and deeds will have some meaning for our grandchildren. For as we are, as Scripture puts it, “children” [banayikh]; we are also, as tradition reads it, “Builders” [bonayikh].

I can think of no better description of what it means to be a mimetic community.

And yet in light of the processes leading to the breakdown of the mimetic community, processes that Rosenzweig described and analyzed with such prescient insight, can one accept his assumption that it is possible to reverse those processes and reconstruct that lost mimetic community? Can the transformation of Judaism from a culture to an enclave be reversed? To revert, for the last time, to the traditional dishes handed down from mother to daughter: In an era when even the most Orthodox Jews are eating kosher—nay, glatt kosher—Chinese, Thai, Italian, and French cuisine, is it possible to imagine that one’s bubbe’s kugel will ever again be as irreplaceable as kashrut?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Israel’s Sea Change

The first Zionist ship was a refurbished English vessel with 20 years of rough service behind her, including the wartime evacuation of Singapore in 1941.

Lives in Translation

The elegant essays in Hillel Halkin's new book are the fruit of a lifetime devoted to Hebrew literature.

The Exilarch’s Lost Princess

In real life, or as much of it as historians can reconstruct, Septimania was a name for the region of southern France that included the Jewish populations of such venerable cities as Carcassonne, Narbonne, and Toulouse. Jonathan Levi leans on the most delightfully far-fetched version of these events in his latest novel.

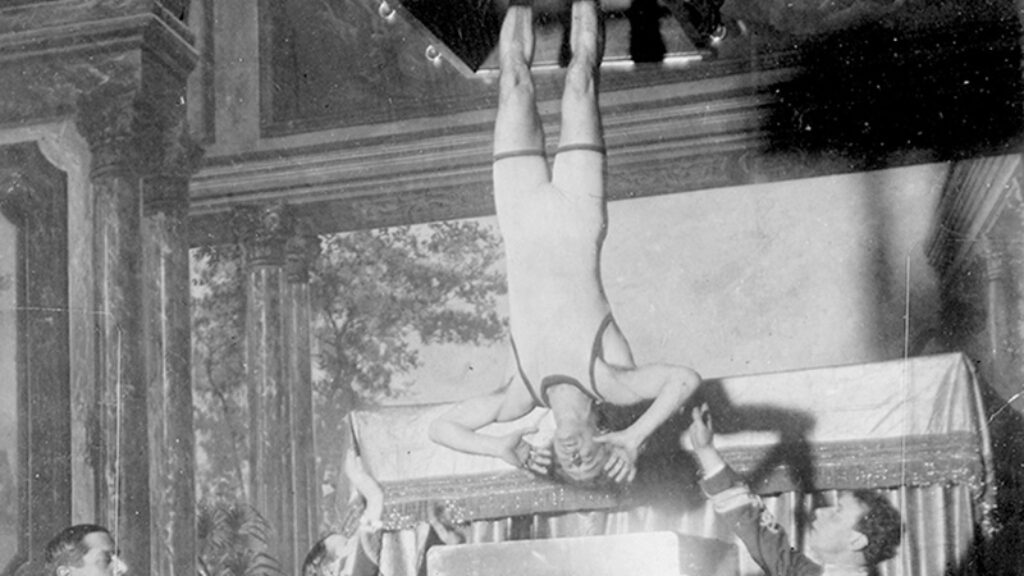

An Entrepreneurial American

“Houdini created his illusions and handed them down to his brother Hardeen, Hardeen sold them to the Amazing Dunninger, and Dunninger sold them to—my father,” writes Jerry Muller in his review of Adam Begley’s new biography of the great Jewish escape artist.

gwhepner

A PARADOX, A PARADOX, A PARADOX

The choice between a consciousness that is without

questions, and another, raising questions all the time,

causes, to resolve the paradigm of doubt,

paradox, which thus prevails as premier paradigm.

Three movements, Orthodox, Conservative, Reform,

raise questions not just by the way in which they have been labeled,

by their common deviation from the norm,

all by paradox empowered, and by it disabled.

[email protected]

gwhepner

A PARADOX, A PARADOX, A PARADOX

The choice between a consciousness that is without

questions, and another, raising questions all the time,

causes, to resolve the paradigm of doubt,

paradox, which thus prevails as premier paradigm.

Three movements, Orthodox, Conservative, Reform,

raise questions not just by the way in which they have been labeled,

by their common deviation from the norm,

all by paradox empowered, and by it disabled.

[email protected]