Living in the USA

After 150 years of social science, we rabbis still commit the error of thinking that the quality of our teachings determines their success. Of course, profound religious ideas are vitally important for living Judaism. Moral aspirations, textured cultural discourse, shared “strong evaluations” about life’s meaning (yes, Rabbi Gordis, Conservative Jews do read Charles Taylor), a sense of shared history and destiny—these are the flesh of the living body of Judaism. But its skeleton is social. And society is subject to forces so very, very large that they are more or less impervious to even the best religious apologetics.

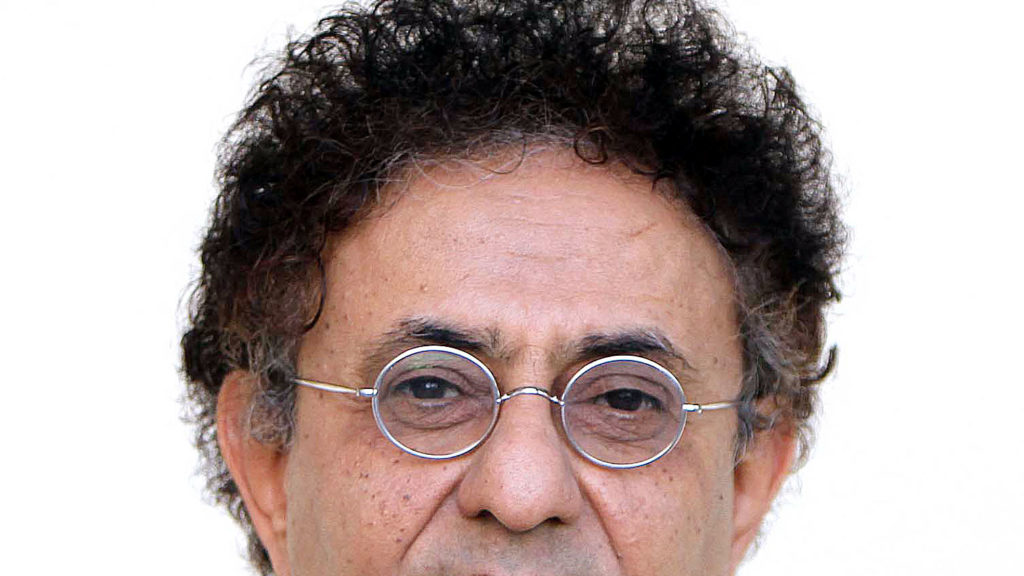

Daniel Gordis’ tearless requiem for Conservative Judaism tells some uncomfortable truths. But attentive Masorti/Conservative readers know that Gordis has no hiddush; for decades, the hometown team has subjected itself to lacerating self-criticism: Our religious vision is paltry, we opt too often for inoffensive American “civil religion,” and some of our representatives have been, frankly, mediocre. I am on record as admitting that our greatest challenge is whether we can claim to offer religious leadership at all. So Gordis is, unfortunately, on target in noting that Masorti/Conservative Judaism is in crisis and that its decline would dim the hope for a literate and traditional yet heterodox faith. But Gordis also clearly does not live in America any more. His comments lack any inkling of recognition that our troubles are mostly in our bones, our society, not in our ideas. He thinks the style of Judaism explains the behavior of the Jews. As we say in the Beit Midrash, punkt fahrkert, it’s the exact opposite.

All of American Judaism—at least outside the ultra-Orthodox enclaves and probably within them too—is conditioned by the historically unique challenges of being American Jews. We work, study, dwell, shop, eat, play, read, vote, marry, and think like our non-Jewish neighbors. In many ways this is wonderful. I am certain that self-reflective Jewish Review of Books readers know how much their views on justice, equality, and freedom, for instance, derive mainly from Western sources, with only incidental Jewish roots. But our Americanness also makes it difficult to remain rooted in Am Israel. If we will not restrict whom we marry, if we do not instinctively gravitate toward faith claims or ethnic loyalties, if we regard the self as the measure of all things and autonomy as the holy of holies, that is not necessarily because our Judaism is so weak or misguided. It is because we are Americans. Enormous, systemic, economic, cultural, technological, social-psychological forces are not likely to change even if they were confronted with a more demanding religious ethos.

Perhaps Rabbi Gordis knew this 20 years ago when he lived in Los Angeles, but forgot it during in his long years in Jerusalem, the place on earth most suited to intense Jewish commitment. Perhaps he never knew it, growing up as he did at the heart of a mid-century Conservative movement that was terrifically proud of its ideology and only barely less triumphalist than Orthodoxy today. The truth is, Conservatism flourished from the 1920s through the 1960s because it was well adapted to Americanizing immigrants and their thoroughly American children. Its success was fertilized by sociology, and its leaders mistook their success for a victory of ideology.

Take, for example, of Gordis’ comments about the 1950s driving teshuvah, which permitted taking the car to synagogue on Shabbat. Like Gordis, I reject this position, but where he sees vacuous hypocrisy, I see an attempt, mistaken but well-intentioned, to contend with a huge social transformation. Conservative Jews didn’t drive on Shabbat because rabbis said they could. They drove on Shabbat because everyone did in Shaker Heights, Encino, and Skokie.

How different is Orthodoxy? I would hesitate before claiming complete Orthodox exceptionalism. Most Modern Orthodox and many not-so-modern Orthodox people also live fully in American culture, although they kasher their dishes better than their Conservative counterparts, order sealed meals at Disney World, and read only pro-Israel web pages on their smart phones. This has consequences. Consider the oft-reported phenomenon of Orthodox teens who keep Shabbat . . . except for texting. Don’t they know texting is a form of writing d’rabbanan? Have they been raised with an insufficiently demanding religious ideology? How about a simpler theory: It’s hard, really hard, to live in a culture without absorbing its norms and behavior patterns. Orthodox Jews might not drive on Shabbat in 2013. But I would place no bets on what they will do with their web-enabled devices in 2030. (And I won’t pry into what their grandparents did with their cars back in 1960, either.)

And if that is true about something as insignificant as txtng on shbbs, lol, how about something as important marrying someone you love? Graduates of Ramaz, Yeshiva of Flatbush, Frisch, and Yeshiva University, have all come to me to help convert the men and women they fell in love with in law school or at work. I am glad that Orthodoxy has, today, a much lower intermarriage rate than we liberal Jews do, but it isn’t zero, and it won’t be. Moreoever, how many Orthodox millennials or Gen-Yers would insist that gay Jews should partner with someone they don’t really love, or should pass up those they do love, in order to conform with traditional norms of marriage? I wouldn’t bet on that either. It is a fantasy to think that halakhic ideology can teach American Jews not to be Americans.

The late 20th- and early 21st-century Orthodox resurgence is not a triumph of frum substance over liberal superficiality. The turn to Orthodoxy is actually part of the same turn toward faith and desire for “authentic” tradition that nurtures evangelicals in America and other fundamentalisms worldwide. As in the days of Conservative ascendance, today’s Orthodox growth is a case where an ideology struck its roots in a fertile social matrix. Partisans should not mistake social trends for vindication of a religious ideology.

Religion exists to orient human life toward the sacred transcendent. But if ideas are to shape people’s souls, they must beat in time with the heartbeat of the zeitgeist. To borrow a neo-Darwinian metaphor, religious memes must provide some adaptive advantage. When Gordis eulogizes Conservative Judaism, I think he is being obscure on just this point. Is this an “it’s-about-time” death of a worthless style of Judaism? Or is he instead making the empirical claim that, whatever its theoretical merits, this religious path is maladaptive for American Jewish society today?

If it is the latter, then the Pew study data constitutes relevant evidence. There is no denying that in the last 30 or 40 years, Masorti/Conservative Jewish ideology has inspired fewer people than it once did. It is too demanding, too Hebraic, too traditional, too ethnic for those turning left toward merely vestigial connection to Jewish identity, yet not enough of any of those things for those turning to the right. And there is no denying that for years Orthodoxy has been in better step with a neo-traditionalist zeitgeist, winning the loyalty of those who want quantitatively more Jewish behavior.

But zeitgeists change and people rebel against the religions of their childhood and families of origin. Just ask Daniel Gordis, or the 59 percent of those aged 50 to 64 who were raised Orthodox but now consider themselves non-Orthodox. I wouldn’t be so sure that the religious ideologies whose apparent passing Gordis remorselessly laments will not reassert themselves. Gordis is correct to note that there are many people for whom Orthodoxy is not an option, on theological, ethical, or “lifestyle” grounds. I believe he neglects to note that some of those same people align themselves with Orthodoxy anyway, tolerating significant religious dissonance for the sake of the other estimable benefits of joining these religious communities.

I myself cannot join them. Instead, I choose to affirm full gender egalitarianism. I choose to contend more directly with the ethical demands of gay people for affirmation. I feel compelled to contend forthrightly with what I know (at least in the sense of “inference to best explanation”) about the history of Jewish texts, including the Bible. I know that the Torah and mitzvot are a result of the human reach towards heaven, not divine dictates to Earth. I am therefore unwilling to behave “as if” a number of ethically dubious features of Judaism come from God himself and can never change. Yet I affirm traditional Jewish practice as a wise and rich spiritual discipline that makes us virtuous people and helps us build a better world. This is our Masorti/Conservative calling card: faithful, critical, traditional, sane.

This message, regrettably, has not ignited mass enthusiasm, but that is a social statement about the tenor of the age, the social ecosystem. The demographic data is horrible. We Conservatives have also squandered too many opportunities, and I have no certain map for how the United Synagogue, Schechter schools, or even The Jewish Theological Seminary will survive on this inhospitable savanna. But, Rabbi Gordis’ polemics notwithstanding, these challenges say nothing about the power of our religious ideas. When it comes to its ideology, Conservative Judaism should hang tight. The really grim question is whether we can hang on long enough for our moment to recur.

As a community rabbi and as a Jew, I will keep plugging away, hopefully, optimistically, persistently. But then, I have no choice; I’m a true believer in the Masorti/Conservative brand of traditionalist heterodoxy.

Editor’s Note: Daniel Gordis replies to his critics and outlines his positive vision for the future.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Manufacturing Falsehoods

An immense echo-chamber has been built, and the line is always the same: Israel is not allowed to be a country like any other.

Father Abraham

Jews, Muslims, and Christians all revere Abraham. But is it the same Abraham?

Thoreau and the Jewish Problem

When my friend and I read Walden, I shuttle between my old paperback, festooned with underlining and marginalia, and Jeffrey S. Cramer’s handsome annotated edition.

Anti-Israelism

It's a new prejudice, not just the old story in a new guise.

charles.hoffman.cpa

"I know that the Torah and mitzvot are a result of the human reach towards heaven, not divine dictates to Earth. I am therefore unwilling to behave “as if” a number of ethically dubious features of Judaism come from God himself and can never change. "

One either believes that the Torah is Revelation or one doesn't. And if one doesn't, than regardless of what bubbe or zayde did, and regardless of what our people ate in Poland or whoever they married in Germany, changing morays and lifestyles can render any element of Jewish law "ethically dubious" and therefore subject to change.

R Kalmanofsky is an impressive speaker - I've heard him often. But if he does not believe in Torah min Hashomayim, then he might look into a different calling for the balance of his professional life.

SDK

And if one does, then what you have is what we see right now in Orthodoxy -- a race to the right. Chumrah upon chumrah. No one serving strawberries. "Shalim" on 4 year old girls. Schools where parents must promise not to use the Internet. Young chareidi men attacking middle aged Modern Orthodox women on busses.

It's bad out there. And the corrective you need is not found in Torah, not Torah as it's taught today in Orthodoxy.

Unquestioning acceptance of fundamentalism, without any corrective, produced the Crusades. It has produced all of the suffering of Jewish history. And so you are saying we should learn nothing from that history -- we went into Exile so that we could return to our Land and eat each other alive in the name of G-d and Revelation.

Are we -- one of the most intellectual of world religions -- really meant to meet the challenge of modernity and humanism and equality and freedom with a return to fundamentalism? I don't think so.

You can go there, but I won't. And neither will the vast majority of American Jews. So if you're willing to write us off, that's fine, but we intend to stay around all the same.

charles.hoffman.cpa

fundamentalism and core beliefs are quite different. but if the basic commandments aren't from God, why bother?

Rogerroad

Mr. Hoffman is of course wrong and his mistake stems from his misunderstanding of the concept of Torah min Hashomayim. To believe that the Torah is the divinely inspired/revealed word of God one doesn’t have to have faith that Moshe sat cross legged while God dictated. That position is the fundamentalist position and Mr. Hoffman is welcome to it but it certainly it has never been a requirement of traditional orthodox Judaism. In fact, our tradition is, generally, that there is no requirement to hold specified beliefs in order to be a good Jew; one has to take – or refrain from taking – certain actions in order to be a good Jew, but there is no “belief/faith” test. (The Rambam held differently, a view shaped his encounters with the larger world.) The belief test Mr. Hoffman espouses is in fact a very Christian notion (salvation through faith, not works). I appreciate Mr. Hoffman’s concerns about the slippery slope of changing morays – but the fundamentalist position isn’t really a satisfactory response for most thinking people of whatever denomination.

charles.hoffman.cpa

I've never defined "torah min hashamayim" to limit it to the "cross-legged Moshe" of the above post. But I do feel that what was given was for its intended purpose; and if one doesn't believe that it came from God, then one is wasting time in synagogue, and should be playing golf instead

And as for the guy standing up front and drawing a salary, if he too doesn't believe that the mitzvot are from God, he'd be better serving his congregants by acting as their caddy for their next round of golf