Conservative Judaism: A Requiem

The numbers are in, and they are devastating. The Pew Research Center’s “A Portrait of Jewish Americans” portrays a community in existentially threatening dysfunction. Some of the numbers are already well-known: Intermarriage rates have climbed from the once-fear-inducing 52 percent of the 1990 National Jewish Population Survey to 58 percent among recently married Jews on the whole. (The rate would be about 70 percent if one were to leave out the Orthodox, who very rarely intermarry.) Only 59 percent of American Jews are raising their children as Jews “by religion,” and a mere 47 percent of them are giving their children a Jewish education. And the communal dimension of Jewish life, which has for millennia been the primary mainstay of Jewish identity formation, is all but gone outside the Orthodox community; only 28 percent of those polled believe that being Jewish is essentially involved with being part of a Jewish community.

Stakeholders in the status quo are running for cover, questioning the Pew methodology, and quibbling with its results. But one fundamental conclusion is inescapable: The massive injection of capital into the post-1990 study “continuity” agenda has failed miserably. Non-Orthodox Judaism is simply disappearing in America. Judaism has long been a predominantly content-driven, rather than a faith-driven enterprise, but we now have a generation of Jews secularly successful and well-educated, but so Jewishly illiterate that nothing remains to bind them to their community or even to a sense that they hail from something worth preserving. By abandoning a commitment to Jewish substance, American Jewish leaders destroyed the very enterprise they claimed to be preserving.

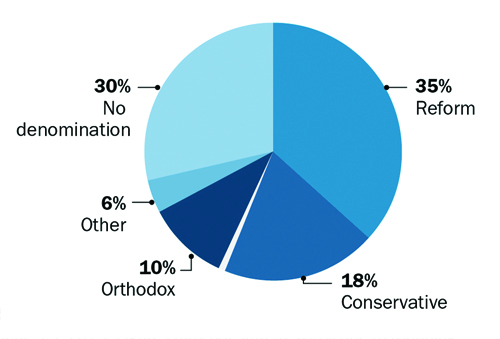

Nowhere is this rapid collapse more visible than in the Conservative movement, which is practically imploding before our eyes. In 1971, 41 percent of American Jews affiliated with the Conservative movement, then the largest of the movements. By the time of the 1990 National Jewish Population Survey, the number had declined to 38 percent. In 2000, it was 26 percent, and now, according to Pew, Conservative Judaism is today the denominational home of only 18 percent of Jews. And they are graying. Among Jews under the age of 30, only 11 percent of respondents defined themselves as Conservative.

Barring some now unforeseeable development, the movement’s future is bleak. As Rabbi Edward Feinstein, one of the movement’s leading pulpit rabbis noted at the recent post-Pew United Synagogue Convention, “Our house is on fire . . . If you don’t read anything else in the Pew report, [you should note that] we have maybe 10 years left. In the next 10 years, you will see a rapid collapse of synagogues and the national organizations that support them.”

The likely demise of Conservative Judaism greatly saddens me. I was raised in a family deeply committed to the Conservative movement. My paternal grandfather, Rabbi Robert Gordis, was in his day one of the nation’s leading Conservative rabbis, a long-time member of the faculty of the Jewish Theological Seminary, one of the Conservative movement’s most articulate spokespeople, and president of the Rabbinical Assembly. My mother’s brother, Rabbi Gershon Cohen, was chancellor of JTS from 1972 until 1986. There are other Conservative rabbis strung along our family tree, me among them. I came of age in the Camp Ramah system, was ordained at JTS, and was the founding dean of the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies, the Conservative movement’s West Coast rabbinical school. Even if I’ve long since meandered to a different religious community, the impending demise of Conservative Judaism means the disappearance of the world that shaped me.

My personal sadness, though, is of no account compared to the loss this represents for American Jewish life. Not long ago, it appeared that Conservative Judaism might be an option for those for whom the rigors of Orthodoxy were too great, but for whom Judaism as a conversation framed around profound issues and texts was still compelling. That was the era in which Conservative rabbis, reasonably conversant in Jewish classical texts and able to teach them to their flocks, could mitigate the increasingly pervasive tendency of liberal Judaism to recast Jewishness as an inoffensive ethnic version of American Protestantism-lite.

But this reframed Judaism, saying little and welcoming all, has proven irresistible to an American Jewish generation to which difference is offensive and substance is unnecessary. Gabriel Roth’s response to the Pew report in Slate is a case in point. He notes, inter alia, “Here are some of the things I cherish about Jewishness: unsnobbish intellectualism, sympathy for the disadvantaged, psychoanalytic insight, rueful comedy, smoked fish.”

That Jewish self-conception must be offensive to Protestants and Catholics, who are entitled to believe that they, too, are capable of unsnobbish intellectualism, sympathy for the disadvantaged, and psychoanalytic insight. But the real issue is that Judaism recast as a variant of American upper-crust social sensibilities simply says nothing sufficiently significant to merit survival. Indeed, Roth then predicts quite convincingly, “For my grandchildren, the fact that some of their ancestors were Jewish will have no more significance than the fact that others were Welsh.”

Conservative Judaism was supposed to have prevented the American Jewish slide into this abyss. Despite the triumphalism so in vogue in contemporary American Orthodoxy, the fact remains that a plurality of American Jews will not adopt the halakhic rigors that lie at the core of Orthodox communal expectations. There are theological, moral, intellectual, and “lifestyle” reasons for that. For those people for whom Orthodoxy was not an option, it was Conservative Judaism that offered a vision of Jewish communities colored by reverence for classical Jewish learning and for Jewish tradition, even if with a somewhat looser adherence to its particulars.

Sans Conservative Judaism, the vision of a traditional, literate non-Orthodox Judaism will be gone. And that is a terrible loss, for Orthodoxy no less than for American Jewish life at large.

Given the enormity of the loss, it behooves us to ask, “What went wrong?” There were many factors, of course. America’s openness proved a Homeric siren-like allure too powerful for many to resist. And then, with no courage of whatever convictions they might have had and animated primarily by fear, leaders of all varieties of liberal Judaism decided to lower the barriers in order to further constituency retention. They expected less of their congregations, reduced educational demands, and offered sanitized worship reconfigured to meet the declining knowledge levels of their flocks. In many cases, they welcomed non-Jews into the Jewish community in a way that virtually eradicated any disincentive for Jews to marry people with whom they could pass on meaningful Jewish identity.

But those, of course, were precisely the wrong moves. When people select colleges for their children, professional settings in which to work, or books to read, they seek excellence. Lowered expectations mean less commitment and engagement; less education means greater ignorance—why should that attract anyone to Jewish life? It didn’t, as it turns out.

Much ink has been spilled on these and other causes of the Conservative movement’s demise, and this is not the place to review the arguments. But one factor has been almost entirely overlooked, and it ought to be raised, because if we can articulate where Conservative Judaism went wrong, we can begin to describe some of the characteristics of what one might hope will arise in its place.

Because many of the leading Conservative ideologues of the mid-20th century had hailed from Orthodox circles, it was important to them to sustain the claim that Conservative Judaism was halakhic Judaism. Yes, they acknowledged, Conservative Jewish life looked very different from Orthodoxy (women could assume roles that they could not in Orthodox settings, for example), but that was simply because Conservative Judaism was reclaiming the “dynamic Judaism” to which the rabbis of the Talmud had actually been committed. It was Orthodoxy that was a corruption of authentic Judaism, they insisted, and Conservative Judaism had come on the scene to protect (“conserve”) the genius of legal fluidity that had always been key to rabbinic Judaism.

That argument was not entirely wrong. In somewhat different and obviously much-softened language, it has even been adopted by some leading modern Orthodox rabbis. Nor was what doomed Conservative Judaism the incessantly discussed vast gulf in practice between the rabbis and their congregants. What really doomed the movement is that Conservative Judaism ignored the deep existential human questions that religion is meant to address.

As Conservative writers and rabbis addressed questions such as “are we halakhic,” “how are we halakhic,” and “should we be halakhic,” most of the women and men in the pews responded with an uninterested shrug. They were not in shul, for the most part, out of a sense of legally binding obligation. Had that been what they were seeking, they would have been in Orthodox synagogues. They had come to worship because they wanted a connection to their people, to transcendence, to a collective Jewish memory that would give them cause for rejoicing and reason for weeping, and they wanted help in transmitting that to their children. While these laypeople were busy seeking a way to explain to their children why marrying another Jew matters, how a home rooted in Jewish ritual was enriching, and why Jewish literacy still mattered in a world in which there were no barriers to Jews’ participating in the broader culture, their religious leadership was speaking about whether or not the movement was halakhic or how one could speak of revelation in an era of biblical criticism.

Who really cared? Very few people, it turns out.

To the irrelevance of the central argument at the core of much Conservative discourse must be added its hypocrisy. These men and women of the pews were not talmudic scholars, but they were sufficiently educated and had enough common sense to know that if combustion on Shabbat was prohibited, then driving on Shabbat simply had to be a violation of Jewish law. So when Conservative Judaism declared, in its (in)famous 1950 “Responsum on the Sabbath” that it was permissible to drive to synagogue on Shabbat, Conservative Jews smelled a rat. Whatever Conservative Judaism was advocating, it was not Jewish “law.” They appreciated, perhaps, being told that they were not sinning when driving to the synagogue (not that “sinning” was a terribly central facet of their religious worldview), but they also knew that a game was being played.

Some rabbis called it like they saw it. Rabbi Emil Schorsch (father of Ismar Schorsch, who later served as chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary) asked, “Too many of our people do not want to observe the Sabbath, whatever excuse or reason you may give them. Why should we play ball with this insincerity?” But by and large, the Conservative movement succumbed to the pretense that Rabbi Schorsch the elder was too honest to sustain.

Slowly but surely, the rank and file understood that they were witness to what was more than a bit of a charade. Yes, a small intellectual elite subscribed to Conservative Judaism’s unique brand of halakhic life coupled, for example, with principled gender egalitarianism, but the vast majority of kids who came back from Camp Ramah or from the movement’s Israel programs seeking a halakhic community found themselves, in the space of a few short years, in the bosom of Orthodox synagogues (a significant and telling phenomenon, however statistically small, that flies entirely under the Pew radar). And those who remained in the movement, by and large, encountered a conversation that simply did not address their need to define their place in the cosmos.

So self-referential has the Conservative conversation become that the movement today continues to insist on the centrality of Jewish law, without so much as even trying to make a case for it. In its recent much-ballyhooed publication The Observant Life: The Wisdom of Conservative Judaism for Contemporary Jews, a massive 981-page tome, Conservative Jews are exposed to discussions of kashrut and Shabbat but also pornography, employing gays in synagogues, neutering animals, and biodiversity. The Table of Contents is both revealing and devastating; astonishingly, there is not a single chapter on why they should care about halakha in the first place.

Instead, the conversation that hasn’t worked for half a century is trotted out once again. In the volume’s Foreword, Chancellor Arnold Eisen reflects the historical bent of most of JTS’s chancellors and writes:

“Law and tradition” has long been the watchword of “Positive-Historical” or Conservative Judaism. That was particularly so in early decades when the movement’s major thinkers in Germany and America struggled to explain what was unique about their approach to Judaism . . . [Solomon] Schechter and [Zacharias] Frankel would have welcomed The Observant Life, I believe; I certainly do.

Eisen is one of America’s greatest Jewish scholars. Yet half a century after Conservative Judaism began its precipitous decline, his language with respect to the centrality of history as a central facet of Conservative Judaism is identical to what my grandfather was saying in the 1940s. Given all that has changed in the world, who is likely to read the 981 pages that follow?

Could matters really have ended otherwise? To be honest, I don’t know. But we also didn’t really try. Looming unasked in Conservative circles is the following question: Can one create a community committed to the rigors of Jewish traditional living without a literal (read Orthodox) notion of revelation at its core? Are the only choices that American Jews have Orthodoxy (modern, or less so), radicalized liberal Jewishness with its wholesale abandonment of tradition, or aliyah to Israel?

American Jews deserved more choices, and a Conservative Judaism with a different discourse at its core might have provided one. Conservative Judaism could have been the movement that made an argument for tradition and distinctiveness without a theological foundation that is for most modern Jews simply implausible; instead of theology, it could have spoken of traditional Judaism and its spiritual discipline as our unique answer to the human need for meaning.

Imagine that instead of discussing whether or not it was halakhic, Conservative Judaism had said to its adherents something like, “None of us come from nowhere. Not so very deep down, we know that we do not want to be part of an undifferentiated human mass, loving all of humanity equally (and therefore loving no one particularly intensely), abandoning the instinct that our people—which has been speaking in a differentiated voice for millennia—still has something to say to humanity at large.”

Imagine that instead of inventing arguments that somehow sought to maintain an effective claim for revelation even after the movement’s infatuation with biblical criticism (which, of course, undermined the most obvious argument for the authority of Jewish law), Conservative Jewish leaders had invoked an argument similar to that of the Catholic theologian Charles Taylor, who reminds his readers:

What is self-defeating in modes of contemporary culture [is that they] shut out history and the bonds of solidarity . . . I can define my identity only against the background of things that matter . . . Only if I exist in a world in which history, or the demands of nature, or the needs of my fellow human beings, or the duties of citizenship, or the call of God, or something else of this order matters crucially, can I define an identity for myself that is not trivial.

That is the sort of argument that mainstream Conservative Judaism (which celebrated Abraham Joshua Heschel’s poetic take on Jewish life but marginalized him from the halakhic-Jewish practice conversation) could have and should have invoked. Life is about asking important questions (think the Talmud), and yes, much of contemporary American culture is self-defeating. And meaningful life is about demands and duties. “That is why we are here,” Conservative leaders could have said. “We need bonds of solidarity, duties of citizenship, and yes, the call of God. Otherwise, we are trivial.”

The movement never wrote the way that Taylor writes, and it never taught its rabbis to think or to speak with that kind of deep existential and spiritual seriousness. It could have, though. It could have invoked Jewish intellectuals, like Michael Sandel, who wrote in Liberalism and the Limits of Justice, that:

[W]e cannot regard ourselves as independent . . . without . . . understanding ourselves as the particular persons we are—as members of this family or community or nation or people, as bearers of this history, as sons and daughters of that revolution, as citizens of this republic . . . For to have character is to know that I move in a history I neither summon nor command, which carries consequences nonetheless for my choices and conduct. It draws me closer to some and more distant from others; it makes some aims more appropriate, others less so.

Arguments such as those would have put the most human, most self-defining, most existentially significant questions of human life at the center of Conservative Jewish discourse, and the result might well have been a very different prognosis for the only movement that was primed to raise these questions. It is true that young Americans might still have opted for triviality; but they might also have returned to something less vacuous as they grew older and wiser.

The moral of the sad story of Conservative Judaism is this: Human beings do not run from demands that might root them in the cosmos. They seek significance, and for traditions that offer it, they will sacrifice a great deal. Orthodoxy offers that, and the results are clear. Liberal American Judaism does not, and it is paying the price.

Those who will live in the aftermath of Conservative Judaism’s demise will live in an American Judaism diminished and robbed of an important voice. This is not the moment for gloating or for self-congratulation—even within Orthodoxy. This is the moment to begin to ask the question that the Pew study puts squarely in front of us: If Orthodoxy is intellectually untenable for many, and liberal Judaism is utterly incapable of transmitting content and substance, is there no option for Jewish continuity other than Israel? There must be. Those who care about the future of the Jewish people had better embark now on the search for what it might be.

Editor’s Note: From The Jewish Week to Ha’aretz, from many pulpits and all over the blogosphere, people have been talking about Daniel Gordis’ “requiem” for Conservative Judaism. We continue this lively, instructive conversation with seven responses from some of the movement’s most thoughtful teachers and rabbis, along with a response from Jonathan D. Sarna, one of the leading historians of American Jewry.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Screwball Tragedy

Picture a Jewish town, located deep in a Polish forest, that hasn’t received so much as a postcard from the outside world in more than a century. Max Gross conjured it up The Lost Shtetl: A Novel, and the result is both screwball and serious.

Ruby Sees Red

"I’m still trying to wake up from this nightmare. I walk in the streets. I see parents with babies. I can’t look. I walk in Riverside Park, I see an older man hugging his granddaughter, and I almost start crying. We have been forced back into Jewish history, into the bloody raw part of Jewish history."

The Lost Textual Treasures of a Hasidic Community

The Regensburg Library at the University of Chicago contains a catalogue of markings and stamps from books saved from Nazi destruction. One such stamp comes from the library of the Karlin-Stolin Hasidim, a collection that might contain the most valuable manuscript for understanding the roots of Hasidism. But where is it?

Not of This World

In writing his first book for young readers, Aharon Appelfeld seems to have split himself and his life story between the two title characters: resourceful Adam, a boy of the land whose knowledge of the forest keeps them safe and fed, and bookish Thomas, a doubter in both faith and his own abilities.

alanlondy

Daniel Gordis always offers cogent and thoughtful comments on contemporary Jewish life. There is an aspect of the history of the Conservative Movement that he did not mention. Rabbi Mordecai M. Kaplan and the Reconstructionist Movement. Kaplan proposed a reason for Jewish observance and continuity rooted in Jewish peoplehood. Kaplan was an important voice in Conservative Judaism but the halakhists could not deal with him. I remember, Rabbi Gerson Cohen, stating to the student body of the Jewish Theological Seminary something like "the Reconstructionist element has been exiled from Conservative Judaism." It was said with a kind of triumphalism. As a rabbinical student, I knew then that Conservative Judaism was doomed. Just telling people that they should be halakhic Jews without offering a coherent historical/sociological reason for it is worthless. Most people can not accept the divine imperative of Judaism but still want to be serious about their Judaism. Daniel Gordis should commended for his honesty.

charles.hoffman.cpa

The reason for the observance of mitzvot is that they were commanded by God. Kaplan's attitude and approach was, at best, a justification for continuing tradition without belief.

It lasted for a small number of people of his generation; but in the next generation there was no longer a feeling for tradition, so the absence of belief just merged his movement with the general tide of soft-core lip-service.

Within 50 years of his passing, Kaplan's movement had become nothing but another set of organizations and institutions without any identity of its own other than the names on the plaques

gershonweissman

Just like Reconstructionist Judaism influenced much of Conservative Judaism despite its own lack of success, Conservative Judaism will continue to influence much of Orthodoxy: eg. the increasing role of Jewishly knowledgeable women (also due to the incredible success of Bais Yaakov schools), the acceptance of college education particularly in the sciences and technology fields, the increasing numbers of haredim who will join the workforce and leave kollels and yeshivot to do so. I also predict that there will be significant numbers of former orthodox Jews who will populate some of the non orthodox movements to express their Judaism. There will be increased secular interest in Jewish texts without affiliation with orthodoxy or any Jewish streams. There will be non orthodox people who will attend orthodox shuls even regularly but will maintain much of their non orthodox lifestyle. Divorce and even intermarriage will increase even w/in orthodoxy. These are readily observable even today.

murrayrudnick80

There is only one reason Conservative Jews are disappearing-they don't emulate the Orthodox. Their children don't attend yeshivot, they don't eat kosher and they mix socially and any other way with non-Jews. That's how the Orthodox keep most of their children from defecting; they don't know any other way to live. But if they did emulate the Orthodox, what would they achieve? They wouldn't be part of this world any more than 99% of the Orhtodox. Of what value would that be?

Andrew Tallis

Well thought out and cogently argued, as always. My perspective is a little off-beat in that I grew up in a completely secular home but my parents sent me to the Young Israel of Spring Valley for four years to prepare me for my bar mitzvah. Talk about cognitive dissonance! What I developed in "Hebrew school" was a love of Jewish history. I also gained the foundation for my own sustained (and still continuing) self-education as a Jew. I spent three semesters of college in Israel, which exposed me to the national Jewish culture. What I have learned is that there exists many parallel streams for Jews of various beliefs or non-beliefs to approach Judaism and live it. I am not religiously observant but I remember that lightning bolt of understanding when I realized many years ago that all traditional Jewish holidays, including Shabbat, are national as well as religious celebrations. For me this was a revelation and a pathway into a form of observance that did not have to be strictly religious. For those of us who are not Orthodox, ranging from those affiliated with other streams of Judaism to the avowedly secular, understanding this allows participation in a way that is ethnically based in the diaspora and nationally based in Israel. The keys, of course, are education and belonging to one or another of the Jewish communities.

Joshua

Orthodox Jews - at least the thinking ones - observe halacha b/c that is what God has commanded and what God wants from them. Then the unthinking ones follow b/c they are born into a lifestyle. I attended JTS, Ramah, etc. - there is virtually no talk about God at all, not to mention what He/She wants from us. If the Torah is from man, and torah shebal peh is only a reflection of the needs of rabbis of the time, then as Gordis states, there are no expectations and halacha at best has a vote but not a veto.

Rich

It is, of course, a masterfully expressed insight. But there is also a history, not only of Rabbinical discussions on modification of law to American realities or sensibilities, but over time a development of a rather inflexible organizational structure or hierarchy that never developed in the more fragmented Orthodox world. For the fifty years of decline, these organizations chose leaders, valuing any number of attributes from talent to money to loyalty. And resistance to the leadership could often be futile. If you thought the Driving Teshuva was bogus, then everything else was tainted. If you had an unfulfilling experience at one Ramah, your place of residence prevented you from latching onto a different Ramah. Yes, people want to be spiritually engaged, they mostly respect the Jewish traditions from observance to compassionate conduct to study of texts. But the purpose of the organizational structure would be to enable that, something that turned out at best inconsistent. Ideology can be very portable. But when the organization acquires a life of its own to the detriment of its mission, the people will just reassemble themselves, whether to an Orthodox affiliation or no affiliation. That seems to be more in keeping with events that evolved over about half a century.

Richard

We have to ask ourselves the following question - Are we committed to modeling a traditional, halakhic religion and inspiring others to follow where we will lead? or are we going to change our religion to make it more "popular".

Mr Gordis feels that Orthodox or Halakhic Judaism is to unpopular or too tough a "sell" to the modern American.

The health of Orthodoxy (per the Pew report 29% of Orthodox Jews did not grow up that way and retention rates are growing amongst younger adults) suggests that being faithful to a set of values speaks to Gen Y and Millenials in a way that being malleable in your beliefs and practices to make yourself palatable does not.

Jonathan D. Sarna

A brief correction to my friend Daniel Gordis' important article. The Pew Study does indeed tell us how many Conservative Jews became Orthodox. On p.11, it shows that 4% of those raised Conservative are now Orthodox and 30% are now Reform. Sadly for the movement, the 4% who became Orthodox were, in my experience, the best educated and most committed Conservative Jews, the ones it was sorriest to lose. Those who moved to the Reform movement, one suspects, were most often Conservative Jews who intermarried.

Stephen

Well said. The driving tshuvah has always been symbolic for me of how poorly the Movement's leaders understand those of us in (or not in) the pews.

The Reform and Conservative movements hate the idea that the Movements are along a spectrum of observance. They'd like to think they each have a distinct philosophy which guides membership. But they are fooling themselves. Most people choose their movement by their level of ritual observance. The Conservative Movement provides a middle and balanced home for those of us who will never be as ritually observant as those in the Orthodox Movement but don't want to give up ritual and custom to the extent that most Reform Jews have.

Yes.. we pick and choose. That may seem horrible on an academic/philosophical level.. but it is reality.... and Conservative Jews pick and choose more ritual/observance than Reform Jews, and less than Orthodox.

Those who are as halachic as the Movement wants us to be are basically egalitarian Modern Orthodox. Rather than recognizing the character of the vast majority of its membership and understanding its "market share," the leadership of the Conservative Movement plays silly games like the driving tshuvah. If we aren't halachic, then we'll just twist things to unnatural angles and call it halachic. We need a movement that meets us where we are.

Like the Reconstructionists say, halacha has a vote, not a veto. I think most Conservative Jews are fine with that. The silly tshuvot just destroy the credibility of the leadership... and clue the rest of us in that they just don't understand the majority of their constituents.... and thus, they are losing us. It is too bad the Reconstructionist Movement never gained the respect it needed to attract significant followers. I believe that most Conservative Jews are basically Reconstructionist (and this isn't new - I've been hearing it for the past 35 years). The Conservative Movement leadership needs to stop promoting a vision of egalitarian Modern Orthodoxy. If the Movement doesn't recognize its market segment and adjust it will fail.. and let down the large numbers of those of us who are comfortable in the middle ground, avoiding the extremes and finding meaning in our Jewish experience.

ARTH

In Sociology there is a concept of "Bourgeoise Religion." That means religion which is a series of rituals and life-milestone events during with God may be evoked, but is not taken all too seriously.

This sort of institutional religion was predicated on what might be called today a traditional bourgeoise lifestyle: early marriage, men and women who had professions, and the family as the organizing structure of society. It was under such structure that Conservative and Reform Judaism thrived, irregardless of the official ideological pronouncements of each movement which really were entirely irrelevant to most of its supposed adherents.

The assumption was that those who grew up in synagogues affiliated with these movements would return to them and join was predicated on other assumptions: that people would marry and give birth to children in their twenties, that the principal goal of Jews with secular educations in the secular world would be to be successful in their professions, and that the reordering of society and thought caused by the 1960's had not happened. Since none of these above stated assumptions are givens in the social and sociological arrangements of American life, the underlying sociological structures which supported these movements no longer exist.

No effort was made to nuture the affiliation of young single adults to the Conservative movement. No effort was made by the Conservatives to nuture a connection to this movement in what became the increasing longer period-of-time between graduating from High School and "settling down."

The collapse of Bourgeoise Religion as an integral structure in the social arrangements of American life is not confined merely to the Conservative "denomination," it is a Christian phenomena as well. More and more, Americans will be divided between the "true belivers" and everyone else.

I disagree with Gourdis' characterization of Aliya to Israel as a true option which ends the ambiguities of secular Jewish identity through transformation into an Israeli. Since that is what he had done, and he lives in Israel, he should know very well that even among many Israelis themselves, there is a dissatisfaction with living in Israel and the potentials for Jewish and humanistic identity available there. The ambitious prefer to leave Israel and realize themselves in the other nations of the West.

Sarah

"...the fact remains that a plurality of American Jews will not adopt the halakhic rigors that lie at the core of Orthodox communal expectations." Don't be so sure. My family abandoned an ever-Reforming Conservative congregation over time and affiliated with an Orthodox synagogue instead. Yes, it meant lifestyle changes (not going out to lunch or eating with non-kosher friends was the hardest)but it also was more spiritually and emotionally satisfying. Living real Jewish values has meaning.

Michael

Daniel Gordis' requiem was very well written, but also perfectly obvious for many years already. Many centuries, in a sense. In his introduction to Perek Chelek, Rambam discusses contemporary, 12th century attitudes towards Chazal (the rabbis of the Talmud). He seeks to address how people relate to many statements by Chazal about the nature of the world to come. Virtually everyone falls into two groups -- the observant people who accept statements of chazal literally and make religion look idiotic, and the non-observant people who take chazal literally and reject them based on such literal understandings. Times haven't changed. We have an Orthodox world where untenable, fundamentalist notions about the nature of revelation and our tradition make it look wacky to outsiders, and prevent it from appealing to 90% of world Jewry. Then we have the remaining 90%, who reject that fundamentalism and assimilate. Attempts at creating a movement in the middle fail, because at its core, religious Judaism needs that fundamentalism in order to inspire those who can live with it to make the sacrifices in time and money and lifestyle necessary to keep the endeavor going. It doesn't make the fundamentalists right -- it just makes them the agents for continuity. Liberal minded, observant Jews are better off finding homes in the liberal enclaves of the Orthodox world, rather than trying to start a movement that reflects some sort of middle ground.

jerome.hoffman

While Daniel Gordis does identify some of the problems, however, his focus on presenting ideas that were advanced by Dr. Heschel is symptomatic of a larger problem. As Doestoevsky recognized in the Legend of the Grand Inquisitor, real people need earthy and passionate ideas, not academic theory. The pulpit rabbis can preach about relevancy issues, but for the rest of us, we need something with more visceral appeal. That is certainly not Dr. Heschel's elegant analyses. Perhaps it is an appeal geared to preserving a dying religion or ethnicity that has endured despite obstacles, or the world of our Bubbies and Zaydas. Part can be a tie to Israel e.g., expansion of birthright to middle age folks, perhaps part can also be an expansion of camplike programs to that generation. First and formost, however, it must be to provide more vehicles for Jews to meet Jews during critical times like the College years. I have no doubt that a new Shlomo Carlback on campuses is worth a 100 rabbis speaking at Hillels.

Rabbi Hayim Herring

A question that my friend, Danny, implicitly raises: are liberal branches of Judaism capable of setting boundaries that they themselves are able to maintain? And-the same question applies for modern Orthodoxy?

Chaim Casper

Sorry, Dan, but your article is Balderdash! The leadership of the Conservative movement always thought of itself as the heir to classic rabbinic leadership. They believed they were the medium between the extremes of Orthodoxy and Reform. However, as Marshall Sklare (the "dean" of American Jewish sociologists) documented it in his classic studies, "Conservative Judaism" (1952) and "Lakeville" (1967), Conservative synagogues of the 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s and even into the 70s were founded by immigrants who wanted a place that would reflect the Jewish traditionalism they remembered from growing up in Europe while being free to do what they wanted the rest of the time. But when their children or grandchildren came of age, they did not have the nostalgic remembrances the parents and grandparents had from Europe. And so the second and third generations either moved from a Conservative experience to an Orthodox experience (the ba'al t'shuvah movement has many former USYers, ATIDniks or Ramah graduates in its midst) or to a Reform temple or they just intermarried. [Which is why Sklare in his introduction to the 1977 edition of "Conservative Judaism" book pointed to the alarm the leaders of Conservative Judaism felt in their own movement as they were unable to keep their youth in the movement.] Albert Vorspan, the late executive vice president of the Reform synagogue organization (UAHC) put it clearly back in the 1980s: He could put the Conservative rabbinic school (Jewish Theological Seminary) out of business by putting a yarmulke on the heads of all the graduates of the Reform rabbinic School (Hebrew Union College). It looks like history is proving Vorspan right.

arth32

Many of those traditionalists were very offended when women began to participate in all areas of the service and resigned from their Conservative congregations. They failed, even, to keep them..

Benjamin Bloomenthal

This article was rather interesting and insightful, however leaving out a very important issue. As a 38 year old Jewish man, who is married to a Jewish woman, I appear to be the anomaly within the Pew study. I intend to pass on our tradition to my son, who will get a thorough Jewish upbringing.

Growing up, my family belonged to many different synagogues. This was a result of my own learning disabilities, and the both Reform and Conservative Judaisms' "country club" atmosphere that turned away many people. On mother's side of the family, we were long time members of Temple Mishkan Tefilah in Newton (previously of Roxbury). My grandparents were amendment on my younger brother and I being Bar Mitzvah'd there, because of their longstanding history with the synagogue. However, being a child with learning disabilities in the 1980's and working with the professional staff (Rabbi and Cantor) who were more about image, it made it a very unwelcoming and uninspiring experience. While I did end up being Bar Mitzvah'd, I did not get the opportunity to read from the Torah (only from the Haftorah). Shortly there after I dropped out of any sort of Jewish education program, nor did I even step foot back into a shul until my brother was Bar Mitzvah'd by Chabad years later. In my subsequent years, I always felt drawn to Judaism, whether it was through Hillel at college, Chabad or Aish Hatorah.

As a result, Conservative Judaism, along with Reform Judaism, appears to be more concerned with its image rather than actually reaching out and making those personal connections to their congregations. It isn't so much about the person you are, but a mere statistic in their budgets, annual drives, and high holiday tickets. Specifically, not focusing on true Jewish education and building communities will doom both movements. Since leaving the movement and running far far away from the egotistical leadership, I have found a warm and comforting home within Chabad. While I am by no stretch of the imagination Orthodox, let alone a Chabadnick; I do find the authenticity of the movement a breath of fresh air, even with their own issues. As a result, in my home, we have Shabbat Dinners, light candles on Friday night and create a Jewish home filled with light.

Perhaps if the movement was serious about stemming the tide of sliding into irrelevance, it would focus on families and Jewish life. Creating a Jewish community based on Shabbatots, education beyond the worthless Hebrew Schools, and creating a warm and welcoming environment may help. Through the help of both Reform and Conservative Judaism, instead of being the people of the Book, we've turned into the people of the look.

Rabbi Arthur Waskow

Rabbi Gordis not only ignored the Reconstructionist movement but also the movement for Jewish renewal, the Havurah movement, and the proliferation of "independent minyanim." Amidst all of these have come extraordinary creativity, often but by no means only energized by half the Jewish people who were formerly excluded from any public shaping of the Jewish present and future or from shaping Torah -- that is, women. (Let alone the additional portion of gay men who were previously stifled from drawing on their own life-experience in reenergizing Torah.

Not surprising that Rabbi Daniel Gordis would leave these out, given his own life-path. Interesting to note how different has been the life-path of Rabbi David Gordis, who helped bring into being a new transdenominational rabbinical seminary (Boston) that while drawing deeply on Torah, Talmud, Kabbalah, and Hassidus, as well as feminism and Eco-Judaism and meditative Jewish mysticism and affirming the full equality and presence of women and gay/ lesbian/transgender Jews -- therefore and for other reasons utterly beyond Orthodox theology and practice -- has attracted an exciting number of exciting young women and men learning with passion and compassion. And carrying Torah into a world that is shaking in multidimensional earthquake.

And Boston Hebrew College is not the only place. The Reconstructionist Rabbinical College has freed itself from the previously useful but now unhelpful strictures of Recon "civilizational" history. Or the amazing flowering of feminist Judaism -- Judith Plaskow, Rachel Adler, Sue Levi Elwell, Phyllis Berman, Nancy Fuchs-Kreimer, and many many more --. Or the participation of thousands of Jews in at least twenty North American cities in Limmud, bringing Torah learning from and to the range of "newcomers" to "deeply learned." Or the seed-sowing and fruitful work of Rabbis Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, Michael Lerner, Art Green, and me (Im eyn ani li, mi li?). Or the emergence of a dozen Jewish organic farms.

Many of these creative rebirthers of Judaism came from the Conservative "movement." Many of them went way beyond it because it was not in fact "moving." But Rabbi Daniel Gordis' diagnosis of the disease has somehow failed to point him toward the healings that already exist.

Shalom, Rabbi Arthur Waskow, The Shalom Center

charles.hoffman.cpa

all of which is fine; but none of which has a sustainability in the sense of a bond with supporting primary education of its members' children while they're otherwise exposed to a purely secular culture; and little of which involves any sort of daily commitment to practicing mitzvot - daily being the operative term.

hanabluma

The Pew study counts at only six percent the number of Jews who identify themselves as belonging to a Jewish denomination other than the three major one. That rather miniscule amount hardly would seem to be evidence of the "healing" that Arthur Waskow claims them to be. Rather,it would seem that moving from what Waskow characterizes as the "unhelpful strictures" of classical civililizational history, hasn't strengthened the Reconstructionist movement at all.

And, although I agree with Daniel Gordis that Conservative Judaism has, for the most part, failed to offer a substantive and meaningful vision for practicing Judaism is 21st century America, I don't agree that its decision to authorize driving to the synagogue on Shabbat was a key blow to its authenticity. It doesn't seem to be much more of a rationalization than the Orthodox broad construction of what constitutes an eruv, or having timers turn on electrical devices that are forbidden to the human hand.

Sadly,what Conservative Judaism has generally offered has been indifferent Jewish education to its children, rabbis who are often neither deeply learned nor even deeply devoted to Jewish life and ideas, large buildings and staffs that make congregational membership expensive but not engaging, and institutional indifference to finding paths to depart from these limitations. It has learned neither from the chavurah movement nor from Chabad that there are Jews eager for serious and intense religious undertakings in settings that are more intimate and accessible than the formal and formidable structures than Conservative Judaism offers.

Maybe nothing would work to rescue any form of American Judaism from the romance of secular Judaism. Or none at all. But surely it's important for what remains of Jewish life to be vital and morally engaged. Any denomination that declines to take a hard look itself and dedicate itself to reforming itself so that it concentrates on the essentials of promoting and encouraging serious Jewish life deserves the decline it's experiencing

Jason

Here is my take on the situation. Those people who are abandoning Judaism do not believe that there is a real covenant between God and the people of Israel. If they did believe this covenant is real, they would stay Jewish. Now, if there is a truly is a covenant between God and the people of Israel, then the Jewish people will be punished by God horribly for breaking the covenant en masse. Is there a flaw in my thinking?

Mark Komrad M.D.

I think Conservative Judaism can and does address the core existential needs, but it requires attention, attendance, time and an adult level of engagement that goes beyond childhood acquaintance with bible stories. It's hard work and most Jews stop that hard work when it is no longer "required" in Sunday school or for Bar/bat mitzvah, leaving most liberal Jews with a child's level of religious understanding and engagement. Orthodoxy is more effective at holding its people in the active-site long enough to enzymatically convert Jewish child minds into Jewish adult minds by making it mandatory to stay engaged--because God expects it of you! Not just your parents (who are themselves modeling"God-fearing"). This theistic trump in orthodoxy powers the momentum required to achieve adult Jewish sophistication far more effectively than mere existential curiosity. Gordis far over-rates the power of existential curiosity, especially at the youthful ages when people either embrace the religious movement or not.

Paul Nisenbaum

Rabbi Daniel Gordis...I agree with your thoughtful and even painful article that highlights the lack of obligation. Everything is optional. More like a Jewish Community Center than a synagogue for prayer and study. You mention Camp Ramah. Well kids have great singing Kabbalat Shabbat experiences at camp, but upon returning home, very few find something similar in their own homes or at Conservative synagogues. And you also mention the ruling for permissible driving on Shabbat. As a result, it became more inconvenient to attend daily minyan, and certainly not living walking distance to synagogues, eliminated folks, especially children, from having the joy of spending Shabbat with friends.

Marsha Dubrow

wrote:

Reading all the comments after Gordis' article, I think Arthur Waskow expressed it best. Gordis makes no mention, overlooks?, the offshoots of Conservative Judaism that have come into their own in the last few decades; Reconstrctionism, Renewal, independent Minyanim, and post-denominational training academies for rabbis and cantors, e,g Boston's Hebrew College and AJR, and now even JSLI. Thinking, caring, compassionate Jews who have abandoned the strictures of the Conservative movement have taken the

best parts of Conservative Judaism with them: the rigorous exposure to Hebrew, Jewish history, literature, liturgy and music in an historical context, and are applying it to other traditions of meaning, breaking down artificial boundaries and barriers and incorporating spiritual 'best practices' from a variety of denominational sources, while inventing new ones. I like to think of myself as one of these. Conservative Judaism may no longer be around in a decade or two, but its legacy will have been to provide the platform, the springboard, for new Judaic practice imagining more relevant to the 21stcentury American Jew. As the Spiritual Leader of a synagogue once part of the Conservative Movement but now 'in the Conservative tradition', we are redefining what's possible in a Judaism without walls and boundaries of denominationally-defined and bounded practice.

Marsha Dubrow

wrote:

Reading all the comments after Gordis' article, I think Arthur Waskow expressed it best. Gordis makes no mention, overlooks?, the offshoots of Conservative Judaism that have come into their own in the last few decades; rReconstructionism, Renewal, independent Minyanim, and post-denominational training academies for rabbis and cantors, e,g Boston's Hebrew College and AJR, and now even JSLI. Thinking, caring, compassionate Jews who have abandoned the strictures of the Conservative movement have taken the

best parts of Conservative Judaism with them: the rigorous exposure to Hebrew, Jewish history, literature, liturgy and music in an historical context, and are applying it to other traditions of meaning, breaking down artificial boundaries and barriers and incorporating spiritual 'best practices' from a variety of denominational sources, while inventing new ones. I like to think of myself as one of these. Conservative Judaism may no longer be around in a decade or two, but it's legacy will have been to provide the platform, the springboard, for new Judaic practice imagining more relevant to the 21stcentury American Jew. As the Spiritual Leader of a synagogue once part of the Conservative Movement but now 'in the Conservative tradition', we are redefining what's possible in a Judaism without walls and boundaries of denominationally-defined practice.

charles.hoffman.cpa

the proliferation of alternatives or offshoots to mainstream Conservative Judaism would be very impressive if not for the sad truth - most exist on such an ad-hoc basis, that their sustainability is questionable at best, and their appeal is limited to groups that are statistically insignificant.

You don't measure the internet by the number of websites - but rather by the amount of traffic; and many of the organizations referred to haven't seen any new blood in 30 years

DSR

I would only make one change to this article. To the sentence: "It is true that young Americans might still have opted for triviality; but they might also have returned to something less vacuous as they grew older and wiser." Add: "They might still."

While the "conversation" within Conservative Judaism may indeed have long been about issues that are irrelevant (or undermined by other aspects of Conservative thought), the conversation now is about "what went wrong." This is exactly the same self-referential tendency that got the movement here to begin with.

Instead, why not ask the following question: how can Conservative rabbis and lay leaders influence their flock to embrace the meaningful aspects of Conservative thought?

Conservative synagogues still have high membership, even if the members are often indistinguishable in their observance from members of Reform temples. The rabbis of these synagogues still have a platform to offer a compelling message. Orthodox rabbis would kill for such an audience.

If I had to identify why Conservative Judaism is in decline, it's because people who ostensibly believe in it focus more on the movement--its meaning, its decline, its struggle for identity--would rather watch it die while offering a complex intellectual autopsy than use its remaining assets to grow it.

iddo99

Rabbi Gordis almost gets it all correct. It is not the dogmatism or sincerity of the orthodox that distinguishes them - it is the dedication by the most senior leadership and the entire layity to the notion that children should be taught aleph beis (see psalms 8). All else follows. Certainly we will not perish from a lack clever rabbis.

cantordebbie

I grew up in the conservative movement- My grandfather was an esteemed cantor/composer/teacher, my father a wonderful cantor and teacher- all in the conservative movement- I sent my kids to day school and was the second female cantor in the conservative movement in l980. After 17 years in the movement and with three rabbis in a row who didn't understand the power of beautiful Jewish spiritual music, didn't want to share the spiritual leadership on or off the bima, and were not supportive of music and prayer unless it came from them... I reluctantly left to work with any rabbi of any denomination who loved cantors and understood the power of music and prayer. I was heartbroken to leave the conservative movement but grateful for finding a spiritual home in a reform congregation where the rabbis have all been supportive, caring and nurturing of all my musical energy and passions. I miss davening in a conservative synagogue, but the culture fostered by many rabbis does not include cantors- the conversations have not included cantors in books, lectures, and even this heartfelt well written article. Where is the cantor's position, voice, presence? We have the ability to touch people and bring them closer through music, prayer, creative ritual and life cycle events. I want to be part of the discussions! I want to be invited to the table to discuss these important issues. I still care about the conservative movement and believe we must all work together to envision a new reality- with all of us sitting, speaking and singing together.

Cantor Deborah Katchko-Gray

Temple Shearith Israel

Ridgefield,CT

www.cantordebbie.com

CRM

I guess we all agree that the Conservative movement is dying. There is no reason for a Halachik movement to exist if its congregation could care less about a Halachik life. I thought it was interesting what Rabbi Waskow wrote: Many of these creative rebirthers of Judaism came from the Conservative movement. It is just proof of the eminent death of the movement. Rabbi Gordis went Orthodox and the rebirthers went in a different direction soon to disappear because the children of these men and women will not remain and live the life of their parents. Eco-Judaism and meditative Jewish mysticism they all sound like fads that will disappear within one generation.

It pains me to think that Orthodoxy is the only hope to Jewish survival. But while the luminaries and rabbis of the Conservative movement remain preaching about God, Halachah, and stating how inadequate the congregants are for not living a life such as these so called leaders, there is no future in view.

We need rabbis that can inspire Jews to be Jewish without the guilt of not leaving up to the standards that they chose for themselves. The Mara D’atra model is dead among liberal Jews. We need a rabbi that can speak well not a rabbi who can decide Halachik matters, because 98% of conservative Jews do not have Halachik needs or issues. Enough of trying to fool ourselves. Maybe there are a few of these rabbis out there, but surely there are not enough of them.

We do not need rabbis who are openly proud of their children for having joined a Modern Orthodox synagogue. We need rabbis that create an atmosphere in their own synagogues where their children and the children of all congregants want to remain involved in after their Bar/t Mitzvah and beyond. There is beauty in Judaism, even in a non Halachik Judaism.

The Conservative movement can survive but only when we accept the reality around us. The solution is not on Shabbat initiatives, Jewish Observance and Teshuvot. But rather by understanding the majority of the Jews, and they are not necessarily the Jews we see today in the pews. We still have an opportunity to reach out to them before they walk away for good; they come 3 times a year. But they will not come back again for a year if the message they hear is of chastisement by rabbis who make them feel small and inadequate.

The congregants cannot be blamed when the message does not speak to them.

The congregants cannot be blamed when the messenger is oblivious to their needs.

The Torah is a living document not a monolithic stone! As a living documents one should NOT be afraid to make it reflect our world today.

Coby Rudolph

I guess I'll present a bit of a counter argument to the one above:

The challenges present in today's Jewish community stem from hundreds of years of the kind of practice of Orthodoxy that did not provide the kind of religious experience necessary to sustain after more than a couple generations, and we're still seeing the fallout in progress.

For generations, the most potent force connecting Jews with Judaism was tradition, including strict adherence to halacha. It wasn't religious passion, or belief in God, or anything of the sort. That adherence and closeness to tradition probably did a decent job of keeping people connected in small monolithic communities, but out in the broader world, it only takes a few generations for traditions to fade away.

It's not surprising that there were lots of Conservative Jews several decades ago. The 20th century saw waves of Jewish immigration to North America, including many who didn't really feel religious but did feel compelled to be "traditional". They were immigrants who didn't daven everyday, but they kept strictly kosher -- at least inside their home. Basically, they didn't feel the need to stay religious, but the Reform movement didn't appeal to them because it, at the time at least, specifically rejected the practices that they held dear out of tradition. In other words, this is a group that was Conservative because they weren't comfortable being Reform, and because they did not find the Orthodoxy they grew up with to be relevant or meaningful in the outside world.

This doesn't let modern Conservative Judaism off the hook by any means. But I'm not sure the focus of this piece is in the right place.

Alan Rubinstein

Rabbi Gordis and the many articulate responses to his article are drawing a revealing picture of the significance and benefits of the Conservative movement, and by extension the Reform, Reconstructionist and other smaller Jewish faith affiliated and independent communities of which I share. The Pew study can only go so far to project what the evolution of the Jewish community in North America and the world may look like. It is also limited in its research methodology and assessment of the Conservative movement and its future.

The careful Pew study reader needs to understand how research of this kind has limitations. When I did my graduate school thesis study of how public school eighth grade student behaviors and actions changed based on social skills training that I designed, it was easy for me to manipulate my findings based on my interpretation of test results and youth interactions with each other. This can very easily be done with the analysis of synagogue affiliations and choices of contemporary North American Jews.

The Conservative Movement and the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism succeeded in presenting an honest appraisal of its success and future challenges at their Centennial Convention Celebration held in Baltimore October 11-15 that I attended. It shall be interesting if the Union of Reform Judaism can do the same for Reform Judaism at their post 2013 Pew study Biennial to be held soon in San Diego this December as it did at its last Biennial held near Washington, DC in 2011. Add to these movement reflections, one has to also appreciate the roles both the Conservative and Reform movements with its synagogues/kehillot played in supporting my own and my extended family member Jewish journeys. Rabbi Gordis’ views and the Pew study findings don’t necessarily take into account these influences on their future predictions.

The Conservative and Reform movements continue to serve many diverse voices that celebrate various traditional and new approaches to Jewish expression in North American Jewish life. Both movements work very hard to offer their own brand of pluralistic positions supported by leadership that provide guidelines for religious practice with commitment to preserving Jewish life in the modern world. Their challenge is to serve diverse memberships that reflect various backgrounds and experiences. At some point in the future, there may be significant collaborations between the movements that may serve the liberal Jewish community in ways the Pew study can’t predict and we can only imagine.

I applaud the efforts of the Conservative movement to “conserve” the essence of Judaism in our modern age. This challenge demands a lot of soul searching for new models of governance, service delivery, outreach, inreach and exploring a new definition of synagogue as kehillah, a deep and sustaining relationship with community. There are conversations taking place to build a collective vision, a Conservative movement committed to reflect upon the many issues and questions that Rabbi Gordis and the Pew study raise.

The Conservative movement operates like a conservatory of Jewish life where traditions are “conserved” and the Jewish heritage shared attractively. Any conservatory of value needs commitment, tending and guarding to survive. The music conservatory is devoted to the preservation, education, creativity and presentation of the musical art. The botanical conservatory is dedicated to the study, cultivation and public display of plants to beautify and benefit our planet. Similarly, the Conservative movement is entrusted to care for a conservatory full of Jewish treasures that includes its own narrative of an impressive 100 year voyage and dreams of its future.

Alan Rubinstein; Cantor Emeritus

Bolton Street Synagogue (Independent); Baltimore, MD

DSR

With due respect to Cantor Rubinstein, the idea of Conservative Judaism as a conservatory strikes me as problematic. The fundamental issue is that while Orthodoxy offers a compelling rationale for keeping the Torah because of its present (not past) value, Conservative Judaism offers a rationale that speaks only to the intellectual elite (and increasingly not even to them).

Coby Rudolph seriously understates that value of faith in past generations. It may have been a simpler and less ideological faith than the one promoted by Orthodoxy today, but faith in God and the Torah was very real to many people. The veneration of "tradition" as such (Fiddler on the Roof style) is an anachronistic, superficial, and ultimately incorrect view of what Judaism in Europe was about.

Conservative Judaism is trying to tell its adherents to believe in something past generations never believed in: the "preservation of tradition" without genuine faith that the tradition has present value and not just the admirable quality of having survived a long time.

Alan Rubinstein

Thank you DSR for your insightful response to my views about the Conservative movement. I feel you are only responding to part of my perspective picture. Using my “conservatory” image further as a model for the Conservative movement, imagine yourself at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. This museum offers you a complete smorgasbord of visual art holdings and exhibits, both permanent and traveling. Your response seems clouded by only comparing the Conservative movement rationale to an Orthodox one. My view of the Conservative movement does not compare itself to any other movement or synagogue/kehillah perspective.

Consider that the Conservative movement functions like a “conservatory” similar to a holding tank or temporary destination point like the Metropolitan Museum. Our Jewish traditions and heritage are expressed through community practice as if we are taking a tour through the museum guided by educated specialists, enthusiastic docents and our learning from practicing artists who are exploring, imitating and teaching the styles of the great masters. Jewish life is experienced by our exposure to the full repertoire brought forth by our own communal history, ritual practice and wisdom.

Using this suggested model as my example, Rabbi Gordis and you seem to put yourselves in only one exhibit hall, or seem to prefer only one guide to organize your tour. The Conservative movement is much more than that to me. From my vantage point, the movement at its one hundred year voyage stage continues to provide me opportunities to grow and participate meaningfully in Jewish life. I also credit the Conservative movement in addition to my Reform upbringing and earlier Reform movement professional involvement to form the gateway that allows me to feel comfortable in all Jewish faith communities regardless of orientation or rationales.

Our North American Jewish community is very special at this time because of the choice of communities it offers us, spanning from humanistic to ultra orthodox. Conservative Judaism effectively bridges our traditions with modernity. It offers an attractive Torah guide book with leaders that help its members wrestle with and seek solutions and peace of mind to the challenges of our day. It asks its members to value the struggle to gain insight and appreciation of Judaism which remain endearing. In turn, it rewards the seeker a good platform in which to continue one’s journey regardless of destination or temporary resting place. This to me is genuine, sincere and satisfying. Shabbat Shalom!

Alan Rubinstein; Cantor Emeritus

Bolton Street Synagogue (Independent; Baltimore, MD

Member Beth Shalom Congregation (Conservative); Columbia, MD

DSR

Cantor Rubinstein:

I appreciate your thoughtful response. I think the underlying issue is that I (and Rabbi Gordis) view the question through the prism of a "marketplace of ideas." But the "marketplace" analogy tends to imply that you only have so much capital (financial, spiritual, or emotional) and you have to buy one thing or the other; whereas you are suggesting less of a zero-sum game in which one can enjoy many approaches without having to exclude others (as in a museum, library, or, nowadays, a Barnes and Noble).

But even going to a library requires a certain level of interest in reading. And nowadays, building even a minimal level of interest is challenging because there are so many other options. The rationale has to be pretty compelling just to get people in the door. I compare Conservative Judaism with Orthodoxy and Reform only because the latter two have been successful, in their own ways, at building a level of interest.

A clear and idealistic (and sometimes simplistic) vision offers something that will get people to come in the door. A less clear and more complex vision will have fewer takers. I am someone who has come around to appreciate the Conservative approach to embracing contradictions that Orthodoxy could not resolve for me. But then, I've been browsing the library for many years; getting people in the door is something else.

ddknoll

The amazingly thoughtful comments above demonstrate that Gordis has struck a nerve. I wonder however whether all is truly lost.In Australia two of the fastest growing congregations are the Conservative/Pluralist ones.Why? There is not enough space here to postulate some all the likely reasons. But here are some: (a) they offer spiritual engagement as well as ritual and tradition; (2) they have engaging and caring Rabbis; (3) an overwhelming number of orthodox congregations employ Chabad rabbis, which has led to nominally orthodox congregants being members of synagogues that they attend as much as three day a year reform Jews (with whom their daily lives share much in common. Large numbers send their kids to a Jewish day school (55% do) but eat treife at home and at McDonalds. Around 40% of us join a synagogue and the synagogues that grow the most are the two Conservative/Pluralist ones and the smaller modern orthodox ones that engage rather than dictate. That is because many of us crave a Judaism that we can relate to, but it is as much about how we lead and who leads us as it is about which Jewish movement they profess.

brooklyndreaming

In the US members of the conservative movement are voting with their feet, adn they are headed in two directions. They are going to Reform on the left and increasing numbers to Chabad on the right. Just visit your local Chabad Center, a significant percentage of those involved are past-adn even some present-Conservative members.

At Chabad they are discovering a loyalty to tradition, coupled with acceptance all despite level of observance. With over 900 centers in the US and Canada, its only a matter of time before Chabad will eclipse the Conservative movement. Chabad becoming a new synagogue movement filled with Jews who feel connected to tradition. The only difference is the direction. Now they are nudged towards tradition, in the past in the Conservative Temples they were being prompted away with the infatuation with egalitarianism and similar causes.

Shalom Melamed

While Gordis provides an excellent religious analysis of the issues with the Conservative movement, poster Benjamin Bloomenthal above hints at what I suspect to be the real reason for the decline: business

It is very easy to get distracted by an intellectual approach when analyzing the failure of what is, in the end, a business. But I suggest we take a look at some of the business reasons for the decline.

Many Jewish temples and agencies are donor driven. This means that their policies, services, presentation, and staff are chosen and designed to please their donors, rather those who attend or use the services. Donors are typically wealthy, older, white, and male. But is that what a future congregation looks like? Of course not. A future congregation is young, mixed gender, and maybe is mixed race.

The problem with growing membership is clear right there- how can an institution designed to please its donors attract members? It can't.

Any young person who tries to attend most Conservative temples find what Bloomenthal describes above as a "country club" atmosphere that turned away many people."

I would suggest to Gordis and the world, in an augmentation of his views, that the decline is mostly related to business reasons. The product offered isn't catering to the market and is only catering to the investors.

Anyone who has walked into a Conservative temple for the first time knows that no one smiles, no one says hi, the Rabbi is very busy talking to the donors, people frown at your clothing and shoes, etc... The wealthy donors who had great sophistication in business "check their business hat at the door" when governing a non profit and forget all of the elements that make a business successful. What they should do is build an institution that caters to its members. As a donor to an agency, I insist that its management spend time with the attendees, not me. I (the donor) is already sold on the product and don't need the attention. But I'm not typical. Most people are involved in philanthropy for selfish reasons- to reduce their guilt or satisfy their own ego rather than truly give to the community.

This does not mean that the role of religion in the success of a temple is any less important, what it means is that the great things offered by the Conservative movement never reach the people- because the environment is so unfriendly to the young families that would be its future.

Is there a solution to this? No. Businesses come and go, in religion it will be no different.

justin finkelstein

Rabbi Gordis' article seems to bring out former Conservative Jews or Orthodox Jews who have been waiting to tell the world where Conservative Judaism has failed. They write as if the major dilemma for Conservatives are losses to the right. Except that it is factually incorrect; only 4% of Conservative Jews have moved to Orthodoxy. Gordis makes the same incorrect assumption. Gordis is peculiarly determined to tie the 1950 decision permitting Shabbat driving to the Pew Study of 2013. No one in my shul walks around complaining about that decision! To say that the driving decision of 1950 led to Conservative affiliation losses of 2013 is like saying that the invention of the printing press led to the burning of books in Nazi Germany. Seems that he skipped over a few events that happened in the intervening years, such as years of sustained growth of the Conservative movement during the 50's 60's and 70's! Alan Silverstein and Elliot Dorff's argument that there are recent factors, like later marriage ages and smaller families, seem much more sensible. I attend a Conservative shul which is successful in making the tradition relevant and accessible, encouraging observance, where the clergy are personal and members feel connected. We're not the only successful Conservative shul in the area either. And we are taught not to be judgmental, which means we don't take off points for driving to shul on Shabbat. I do not agree, as some try to assert, that the Conservatives leaving for orthodoxy are always the most committed and the cream of the crop. My observation is that they are often the most judgmental, least tolerant of others and all too willing to search for and find "inconsistencies" with others. The future of Conservative Judaism will not be decided by those to the right, but by those more moderate who can embrace the idea of different but equally authentic conclusions to Halachic questions.

The future of Conservative Judaism will also not be determined by Rabbi Gordis. Hailing from a family formerly of the Conservative movement, Rabbi Gordis has no more expertise about American Judaism than any other knowledgable Israeli who used to live in the USA. Going on speaking tours is not the same as living in America. Rabbi Gordis must believe he has a special insight on Israel because he lives there. By the same logic, he should be more modest and less presumptuous about analyzing the religious data from America, a place he no longer resides. That Theodore Herzl's family did not remain Zionists did not spell doom for Zionism; that Robert Gordis' family did not remain Conservative Jews does not spell doom for Conservative Judaism.

Geraldo Coen

A question to Rabbi Gordis: the focus of your analysis is the flaws of Conservative Judaism. Could'nt it be the problem lies with Modern Orthodoxy? For centuries Judaism has been inclusive and pluralistic. Every one was a Jew, from the Am Haaretz to the knowledeable Rabbi. But from a few decades we have this very strict Orthodox Judaism saying that theirs is the only Judaism, all other are wrong. So, between a rigorous, formally oriented, restrictive and excludent Judaism, and no Judaism, many young people choose the later. They simply don't know that Judaism is more more richer than Orthodoxy. What you think of this?

Thank you

Eliezer Diamond

I wonder if Daniel Gordis read my essay on Talmud Torah in The Observant Life. If he had he would have noted that I address the very issues that he deems - correctly - to be essential to a serious discussion of what it means to be a deeply engaged liberal Jew. Among other subjects, I consider what it means to study the Bible as Torah if one believes it to be a humanly authored document, whether and when the study of astronomy is an act of Torah study, and whether reading stories by Agnon or Amos Oz can be considered talmud Torah. I raise these questions not as intellectual parlor games but rather to force readers to think what the term "talmud Torah" or Torah study - one, like halakhah, bandied about so confidently yet carelessly - means in their lives. In particular I want them to think about the difference between studying Judaism and studying Torah, an oft-ignored but crucial distinction.

sklein19

Rabbi Gordis wrote: "a small intellectual elite subscribed to Conservative Judaism’s unique brand of halakhic life coupled, for example, with principled gender egalitarianism..."

Is principled gender egalitarianism Judaism?

jtlandry

Thanks for this thoughtful essay. I wonder if Conservative rabbis really had as much freedom to work with as Rabbi Gordis suggests. As Jonathan Sarna suggests in his book American Judaism, when many of the massive wave of pre-WWI immigrants settled down and joined synagogues, they did so more for social and cultural reasons than for religion. They saw their largely suburban shuls as social and educational centers. They didn't want the strictures of Orthodoxy, but they didn't want to join Reform congregations because these were dominated by the pre-1880 old guard that had always looked down on the immigrants. Like secular Israelis now, they also looked down on Reform for not being real Judaism. With the Conservative movement they could have true Judaism (this is why the rabbis were so insistent that they followed Halachah), but without the practical strictures of Orthodoxy. In that situation, it might have been difficult for the leaders of the movement to come out with a serious halachah along the lines of what Rabbi Gordis describes. But fast forward to the present, and as others have said here, it isn't too late for the movement to start now. Just look at the popularity of Jewish meditation, which has many of the ingredients that Rabbi Gordis calls for. It's grounded in the tradition (Chasidism and kabbalah) so it has some authentic; its proponents talk a great deal about why we should follow it, and it involves some real discipline and sacrifice. Devising a modified halachah that would be traditional enough to feel authentic, yet liberal enough to work under new social conditions, would be harder than this, but still possible. Just look at what the rabbis did after the fall of the temple.

Alan Rubinstein