The Wizard of Words and the Baggy Monster: Rereading Amos Oz’s A Tale of Love and Darkness

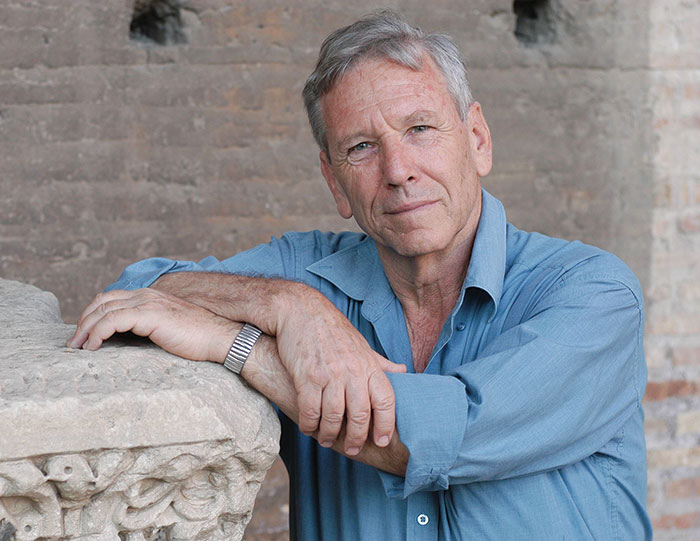

Amos Oz, whose death at the end of 2018 left a gaping hole in the fabric of Hebrew and Israeli literature and culture, was always more than just an author. Oz was a symbol—almost a fetish—of who we Israelis thought we were or fancied ourselves to be. He embodied every captivating quality, be it real or imagined, of the mythological sabra: he was brilliant yet humble, sophisticated and self-aware but not neurotic, highly idealistic but also tolerant and pragmatic. Even his casual good looks reflected the fantasy of the ultimate sabra, the golden boy of the kibbutz, and the Zionist dream.

But this near-hysterical embrace also had its dark side. The literary scholar Yigal Schwartz, who also served as Oz’s editor, called Israel’s unbalanced relationship with Oz a “bipolar reading disorder,” with Oz “treated as son of the gods, but also as a scapegoat.” In his book on Oz, Schwartz wrote, “His readers are swept by his eloquence and charisma but are, at the same, repelled by them.” But it wasn’t just Oz’s eloquence and charisma that alienated readers (and, even more so, the critics) after a certain point in his career. It was also his tendency to speak in first person plural, even as he masterfully and sensitively depicted the marginal characters; the ease with which he assumed the prophetic mantle and spoke in the name of the collective ethos; and, finally, a certain air of entitlement, perhaps even smugness, that started to tick off many readers who had previously been drawn to his work.

It is hard to say exactly when this backlash began, but one marker of the change was when literary journalists began punningly calling Oz the “Wizard of Words.” Whenever this change happened—and, to be fair, it happens at some point to virtually every novelist who becomes identified with his national culture—the moment at which the Israeli literary public decided it loved Oz again is clear: with the publication of A Tale of Love and Darkness in 2002. Why was it this baggy monster of a memoir, of all books, that re-endeared Oz to the Hebrew reader and, even more surprisingly, to countless readers around the world?

This turn of events surprised Oz himself. What about this rather clumsy almost-600-page memoir, strangely described by the author as “fictionalized,” made so many readers embrace Oz and love to love him once again? The book was translated into some 30 languages, including Arabic, and adorned with many literary honors, including Germany’s Goethe Award. It even made it to Hollywood, where it was discovered by Natalie Portman, who directed and starred in a film of the same name, though it did not possess the same beguiling qualities and sank quickly after a few film festival showings. Oz himself stated more than once in interviews that he had expected only a small circle of readers, whose experiences and backgrounds were similar to his own in British Mandate Palestine and the early years of Israeli statehood, to fully appreciate and enjoy his memoir. But this historical obscurity—Oz’s evocation of a forgotten Jerusalem—is not really what makes A Tale of Love and Darkness such an unlikely candidate for worldwide critical and commercial success. Rather, it is the uneven literary texture of the memoir, its structure (or the lack thereof) that one might have thought would have interposed itself between the book and its reader—and yet, bafflingly it was precisely this book that brought Oz back into the readers’ and the critics’ graces.

A Tale of Love and Darkness meanders back and forth in time, from Oz’s melancholic and rather marginal childhood in British-governed Jerusalem to his awkward youth as an outsider in the kibbutz, from there back to his family’s history in Eastern Europe, through to his childhood recollections and on to some memorable moments in his adult life. At the heart of the story, we find the complex and, at times, tormented relationship between the young Oz, an eloquent and imaginative only child, and his doting yet demanding parents. His father, Yehuda Aryeh Klausner, was a highly educated and intellectually ambitious man whose work as a librarian in the national library on Mount Scopus did not meet his own aspirations. His mother, Fania Klausner (née Mussman), was a sensitive young woman who unsuccessfully battled depression. The memoir is filled with many colorful adult characters (and very few children), some of whom are well-known historical figures such as Oz’s great-uncle, Professor Joseph Klausner, a controversial and internationally renowned scholar of Jewish literature. He wrote, among other works, an early biography of Jesus as a Jew and was Chaim Weizmann’s right-wing opponent to be the first president of Israel. (Oz’s sheepish father lived in his shadow.)

We are also introduced to the captivating figure of the great Hebrew poet Shaul Tchernichovsky, who was a friend of Fania’s family and a regular visitor in their home in Odessa, where he used to appear in the company of beautiful young Russian women to banter with his friend, Chaim Nachman Bialik, modern Israel’s national poet, who is described as an amiable glutton, always ready for a lavish feast. Another familiar historic figure who makes an appearance in this memoir is Nobel laureate Shmuel Yosef Agnon, an intriguing character who lived across the street from Oz’s great-uncle Joseph Klausner and did very little to hide his dislike for him. Especially touching is the relationship of the young Oz with his elementary school teacher, the great Hebrew poet Zelda Schneurson Mishkovsky, a direct descendant of the third Lubavitcher Rebbe, whom Oz charmingly refers to as Morah Zelda and on whom he has his first literary crush. We even meet David Ben-Gurion, the short, big-bellied father of modern Israel whose larger-than-life presence fills his austere, almost monastic office, to which the stunned young Oz is summoned very early one morning in order to listen to “the Old Man’s” grandiose musings about philosophy and especially Spinoza, with whom he was famously obsessed.

We are also introduced to an array of less famous but artfully portrayed characters, and, through them, we witness a world that is long gone: frightened and often frazzled Jewish immigrants, who carry with them the burden of diasporic life with all its fear and uncertainty; Arab aristocrats with their air of worldliness and elegance; quirky British officials; and representatives of the young sabra generation, Oz’s peers with whom he never really seems to fit in. This intricate web of stories, acquaintances, and memories is strung together with great detail and unfolds at a pace that seems to be taken from another time and another place.

And yet, the very characteristics that make A Tale of Love and Darkness a unique reading experience are also the ones that make it an unlikely candidate for global recognition in a world where accessibility and success have become almost synonymous. Moreover, the intricate web of memory and meaning is very loosely woven. The best way to describe the novel’s structure is that it doesn’t really have one; the reader is nearly drowned in an abundance of details, which often do not serve the story and, at times, feel nothing short of self-indulgent. The book’s amorphousness, for lack of a kinder term, was not widely addressed by the critics, but it did not go completely unnoticed. Ariana Melamed—in a uniquely hostile review sardonically titled “Amos Klausner, an Author?”—called A Tale of Love and Darkness a “structureless story, leaping capriciously back and forth.” Melamed addressed the overwhelming abundance of details with similar readerly impatience:

What to do with this beaten, used, wrinkled pile of clichés? . . . A huge pile of totally uncommitted images that overwhelms all that Oz has to say. And he indeed has very little to say.

Melamed’s hostile outburst was exaggerated and uncalled for, but it also called attention to literary failings that more “civilized” critics let pass in their reviews.

A Tale of Love and Darkness’s textual looseness is particularly shocking given the outstanding tightness of texts typical to Oz, whose claim to fame was precisely his linguistic “wizardry,” the almost supernatural perfection of every paragraph, every sentence, and every word. By contrast, Oz’s memoir holds at least two books within it: the first is his mother’s tragedy; the second is a Proustian evocation of the unmediated flow of deep memory. The relationship between these two different books, squeezed beneath the same title, is not always harmonious. They interrupt each other, disturb each other’s flow, and, at times, even seem to fight over the gaze of the reader like two attention-starved children whose tired parent (or author) cannot control them.

The main plot of Oz’s Tale is heartbreaking and revolves around the psychological deterioration of Oz’s mother, Fania, a delicate foreign flower who never set root in the harsh reality of Mandatory Jerusalem, the melancholy of which slowly seeps into her, developing into a full-blown depression that takes her away from her husband and only child and eventually pushes her to suicide. This plot, which was also the basis for Natalie Portman’s cinematic misadventure, was first introduced in the young Oz’s brilliant 1976 novella The Hill of Evil Counsel, which is often—and, in my view, rightly—considered to be the pinnacle of Oz’s work. But unlike the tight, mesmerizingly beautiful prose of The Hill of Evil Counsel, in which Oz’s loss of his mother is transformed into her abandoning her family and leaving the country in the company of a high-ranking British officer, the plot in A Tale of Love and Darkness is spread thinly over too many pages. It catches the reader almost by surprise every time it resurfaces between the countless anecdotes, observations, and musings that fill this memoir’s pages. The reappearance of those intense snippets of tragedy, it seems, take not only the reader but the author himself by surprise, as if he himself has forgotten its existence:

I forgot, just as I forgot all about the morning I came home early from school and found my mother sitting quietly in her blue flannel dressing gown, not in her chair by the window but outside in the yard, in a deck chair, under the bare pomegranate tree, sitting there calmly with an expression on her face that looked like a smile but wasn’t; her book was lying as usual upside down open on her lap and torrential rain was pouring down on her and must have been going so for an hour or two, because when I stood her up and dragged her indoors, she was soaked and frozen like a drenched bird that would never fly again.

Is this “forgetfulness” deliberate? Does it represent a sophisticated denial mechanism that allowed the young child to survive the tragedy of his mother’s depression? The reader does not get an answer to this question. One has to cross such a vast distance to land on this harrowingly beautiful description that seems like an island surrounded by a sea of words. The reader feels conflicted: on the one hand, there is an urge to give the masterful Oz credit and believe that the disproportion between words and story is deliberate, but, on the other hand, there is a nagging suspicion that this is not so much a literary strategy as a simple deficiency of editing. There is a rumor that many editors tried and failed to rein in text and author, and certainly the phenomenon of authors who are “too famous to edit” is well known. But Oz is not generally known as such an author. (Craftsmen like Oz tend to appreciate another expert eye.) In any case, A Tale of Love and Darkness stands out among Oz’s works in its apparent need for a firm editorial hand.

A typical Oz text is extremely economical in its words, almost hermetically tight, at times to a fault. His previous novel, The Same Sea (1999), to take the most extreme example, forsook mere prose altogether and was written in austere verse, pleasing a few Oz connoisseurs and leaving behind many other baffled readers. Here, in his great memoir, the language is far from perfectly chiseled. At times, the reader senses something frighteningly close to logorrhea. This is manifested in the erratic, seemingly careless movement between an almost pompous “high” Hebrew and an almost sloppy everyday language. (Nicholas de Lange’s excellent English translation diplomatically softens some of these effects.) “The enormous gap between the banality of the description and the sublime nature of the language is burdensome, irksome, and even infuriating,” wrote the unforgiving Ariana Melamed on this aspect of the memoir. “Not every beating of a blanket is a scene from Don Quixote, and not every carp swimming in the bathtub is Moby Dick.”

An extreme example of such stylistic sloppiness is a totally misplaced mini-chapter in which Oz’s storytelling comes to a screeching halt and he assumes the tiresome didactic tone of a lecturer about what is “true” and what is “false” in his work. Indeed, one cannot help but suspect that this is indeed a ready-made lecture that Oz chose to cut and paste into the memoir, taking advantage of the editorial void. This disturbance in the stylistic and thematic flow of Oz’s Tale (which was wisely omitted from the English edition) is, unfortunately, not the only one in this long journey.

The lack of editing is evident not only at the level of language and structure language; there is also a strong repetitive element that does not feel deliberate and has, as far as I can tell, little poetic or rhetorical value. This is especially jarring in places where the story is actually enchanting, such as the scene in which the young Oz and his parents pay their biweekly visit to the famous great-uncle’s house. This scene is a favorite of Hebrew readers, in part because young Bibi Netanyahu makes an appearance in it as a naughty young boy who, together with his famous brother, Yoni Netanyahu, the fallen hero of Operation Entebbe, hides under the dining room table and keeps undoing Oz’s shoelaces. Their antics are put to an end by a sharp kick dealt by the young Oz to one of the mischievous Netanyahu siblings. “To this day,” he remarks, “I don’t know which one of them I kicked, the heroic brother or the clever one.” (Strangely, this anecdote was omitted from the English translation.) However, the scene begins with a long, slow-paced description of the family’s journey across the landmarks of old Jerusalem, bringing them to the doorstep of Professor Klausner’s house in the Talpiot neighborhood, the door of which is adorned with a copper tablet bearing the professor’s famous motto, “Judaism and Humanism.” The description of their visit is one of the highlights of the reading experience as it captures the melancholic sweetness of the early days of Jerusalem and the as-yet-unfulfilled Zionist dream. But even here, the excruciatingly slow pace and the endless repetitions, the arbitrary breaking into subchapters, all try the reader’s patience.

A more surprising and substantive challenge to the contemporary Israeli reader is Oz’s palpable sense of nostalgia for the days in which Jews felt and behaved like a minority in what would become Israel. In spite of the many references to national and, at times, nationalistic sentiments that run in the boy’s family (they were prominent Revisionists, opposed to the establishment Labor Party), the text itself seems to long for the days when the essence of the Jewish settlement in Palestine was still diasporic. Oz refers with awe and admiration to the pioneers of the kibbutz, the heroic and distant role models of his childhood, but, as an adult writer, he spends much more ink describing situations and states of mind that are very far from heroic or autonomous. A wonderful example of this is his description of his family’s preparations for a disastrous visit to the home of an aristocratic Arab family:

Our visit to Silwani Villa was not like Lenin visiting the workers or like Tolstoy among the simple folk: it was a special occasion. In the eyes of our more respectable and enlightened Arab neighbors, who adopted a more Western European culture most of the time, Uncle Staszek explained, we modern Jews were mistakenly portrayed as a sort of rowdy rabble of rough paupers, lacking manners and not yet fit to stand on the lowest rung of cultural refinement.

These words and the sentiment that they encapsulate bear no resemblance to the self-confidence, even arrogance, of contemporary Israeli culture. Our historical memory is short, and the days of our being an insecure minority in what we believed was our historical homeland are long forgotten, not only by us but by the world.

What is it, then, that makes this very imperfect book so captivating? What is the secret of its success? Is it the fact that it gave us, to quote Yigal Schwartz again, “what we need most and receive only in truly great works of art: the dense, tangible, rich, almost eternal sense of time, the like of which we’ve experienced only in our childhood”? Is it, perhaps, a secret fatigue from our heroic national narrative and a paradoxical yearning to return to a more marginal existence?

Or is it, rather, the imperfections of A Tale of Love and Darkness that make it strangely accessible? Early on, Oz was admired for his sovereign mastery, the chilly perfection of his work, but this same quality eventually distanced readers and critics from him. Perhaps it was the vulnerability of this warm, rambling memoir that enabled readers to reconnect to Oz. Was our wizard easier to love when he stepped out from behind the curtain of perfection and revealed himself to be a frail old man who, no longer in possession of linguistic magic or prophetic confidence, dared to show himself as he truly was, as we all will be, alone and obsessed with his sweet and terrible memories?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Ruined House (An Excerpt)

In 2014 Ruby Namdar won the prestigious Sapir Prize for his novel Ha-bayit asher necherav, the first time in the award’s history that it went to a writer not living in Israel. On November 7, 2017, Harper released it under the title The Ruined House: A Novel, in an English translation by Hillel Halkin. The Jewish Review of Books is pleased to present this excerpt from the novel’s opening.

On Agnonizing in English

For the Hebrew reader, S. Y. Agnon is not merely canonical, he stands almost outside of time.

Agnon, Oz, and Me

Over the years, I’ve spoken privately with several Israeli novelists but with only two of the internationally famous ones. And these very brief conversations took place more than 40 years…

At Professor Bachlam’s

A lost chapter from Agnon's final, classic novel Shira, translated here for the first time.

Marcus Moseley

Autobiography is not the "well wrought urn" of New Criticism.

As Leonard Cohen says: "Everything is broken--that's how the light gets in"!

Again, citing Cohen "This is a very broken and very lonely Hallelujah".

(The same criticisms as above were leveled against "War and Peace"--esp. Henry James and Lubbock).

I do wonder whether Oz intended (and there is much that he did not intend in this book which is precisely why it reveals--esp the embarrassing chapter that was omitted--mistakenly in my view--from the English tr. as mentioned above) to resonate "War and Peace" "Love and Darkness": the two are the North and South Poles of Oz's stuff)!

Thanks for a thought-provoking review.

MM