The Ukrainian Question

“If I had to choose between Hitler and Stalin,” says the veteran Polish dissident, activist, and essayist Adam Michnik, “I pick Marlene Dietrich.” Although Vladimir Putin is no Stalin and the new Ukrainian government includes no Hitlers, many Ukrainian Jews know the feeling. As the conflict deepens, however, this option will become increasingly less viable, especially given the surprisingly important role played by Jews—now reduced, in what was once the heartland of European Jewry, to a population variously assessed at from 70,000 up to 300,000 in a nation of 47 million—in the ongoing contest between Russia and Ukraine. The Ukrainian Jews’ part in the actual struggle for Ukraine’s independence (and eventual membership in the European Union) is, to be sure, a marginal one, even if they were somewhat over-represented among the martyrs who died in the Maidan protests that eventually toppled Prime Minister Victor Yanukovych’s corrupt government. It is otherwise in the propaganda war.

Over the last few months, Putin and his Foreign Ministry have repeatedly justified Russia’s annexation of Crimea and encroachment on eastern Ukraine by arguing that it was necessary to counter “nationalist, reactionary, and anti-Semitic forces,” describing the new Ukrainian government as a “Nazi regime.” In fact, of course, it is Putin whose actions are somewhat reminiscent of Hitler’s Sudetenland and Austria land-grabs of the 1930s. Then again, Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk’s government does include the Svoboda (Freedom) and Pravy Sektor (Right Sector) parties, both of whom trace their lineage to wartime Ukrainian leader Stepan Bandera and his Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). Bandera and the OUN collaborated with the Nazis in mass murder of Jews and Poles in World War II. The same OUN eventually turned its guns against the Germans when they failed to promote Ukrainian independence and then against the Soviets, who had chased the Germans away, but had no intention of supporting Ukrainian nationalism either. To Ukrainians in the west of the country, the OUN are national heroes; in the eyes of those in the east (including many of the descendants of the Soviet troops who fought them) and to Russians they are traitors.

Jewish or not, one should find the approval of such heroes deeply troubling, but Ukraine is hardly alone among Eastern and Central European countries in struggling with this problem. With the exception of Poland, the Czech Republic, and Serbia, all of the other countries in the region (or their predecessors) threw in with the Axis against the Allies in World War II. This is not surprising, given that in this part of the world the Allies meant Stalin, who had, among his many other crimes, deliberately starved some four and half million Ukrainians to death just a dozen years earlier.

The nations of Central and Eastern Europe are left with the unpleasant history—and heroes—that they have, and they will not reject them. One can hope, however, that they will reject some of the things they stood for. It should be noted that Ukraine’s problematic national heroes do not start with Bandera. Bogdan Khmelnitzky is remembered by Ukrainians as a father of the nation and by Jews as the perpetrator of the horrific massacres of 1648–1649. Both descriptions are correct. His was the worst name known to Ukrainian Jews until Hitler’s death squads and their local accomplices killed more than a million of them.

Nonetheless, support for the two Ukrainian extremist parties remains extremely low. Despite its members’ heroic involvement in the Maidan demonstrations, Svoboda received just 1.16 percent of the vote in the recent May presidential elections that brought billionaire candy maker Petro Poroshenko to power. Pravy Sektor polled 0.7 percent. Together, they received fewer votes than Vadim Rabinovich, president of the Ukrainian Jewish Parliament, who ran as an independent. This outcome hardly represents the neo-fascist threat of Putin’s propaganda. Of course, conflicts like this tend to stoke nationalism, so a resurgence of the extreme right cannot be ruled out. These groups owe their current support to their role in fighting Yanukovych’s brutal riot police, and a fight with Russian invaders would do wonders for their popularity.

On April 28, 2014, Gennady Kernes, the somewhat pro-Putin Jewish mayor of the important eastern Ukrainian city of Kharkiv, was shot in the back by a sniper while jogging. The bullet just missed his heart, and after emergency surgery he was flown to Israel for further treatment. But Kernes is one of Ukraine’s most politically controversial and personally flamboyant politicians (“Of all the mayors,” he recently told a reporter, “my Instagram account is the best”), so it is anybody’s guess as to who was behind the assassination attempt.

There have, however, been acts of explicitly anti-Semitic violence against Jews and Jewish institutions in Ukraine over the last few months. A rabbi was attacked in Kiev; a synagogue was firebombed in Nikolayev; and a Jewish memorial was defaced in Sevastopol, but responsibility for these acts has yet to be ascertained. Russia does engage in provocations: At first Putin disowned the “little green men” who took over Crimea, but then he recognized they were his own army. So it is not inconceivable that Putin’s men might have been behind these attacks. On the other hand, the most publicized anti-Semitic act so far has been the distribution of leaflets demanding that Jews register with the separatists in Donetsk as potentially disloyal. These have now been debunked as forgeries meant to besmirch the pro-Russian separatists. However, Ukrainian Prime Minister Yatsenyuk promptly condemned the ploy.

Ukrainian Jews, meanwhile, have overwhelmingly thrown their support behind the anti-Yanukovych and now anti-Russian movement. It is perhaps telling that no pro-Russian Jewish declarations emerged from Crimea after the takeover. In Russia itself, Jewish organizations have been largely silent: Only Chabad Chief Rabbi Berel Lazar, a long-time Putin supporter, has come out with an endorsement of Russia’s actions. It remains to be seen how newly elected President Petro Poroshenko’s rumored Jewish roots will impact the changing political landscape.

Interestingly, Israel was one of a dozen countries absent during the UN General Assembly vote reaffirming support for Ukraine’s territorial integrity. This abstention was widely considered pro-Russian, and Israel—citing concerns over Russia’s influence in Syria and Iran—refused to budge even in the face of American pressure. It must be remembered that Israel’s foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman, an immigrant from then-Soviet Moldova, has been consistent in his sympathy for Putin’s policies.

Are Jewish interests and values better served by the emergence of a democratic independent state, even if it is steeped in nationalist ideology? Or are they better served by the triumph of Russian regional imperialism, even if it is tempered by a demonstrated opposition to anti-Semitism?

One way to answer the question is to look for analogies. In 1980, when the Solidarity movement confronted the Poland’s Communist regime and its Soviet patrons, Jewish observers were torn between sympathy for its democratic struggle (full disclosure: I was part of it) and concerns about its Catholic and nationalistic ideology, as well as a resurgence of anti-Semitism in some parts of the movement. Even as late as the mid-1990s, when a now-free Poland was lobbying for NATO membership, some critics considered it too stained by anti-Semitism to qualify. Most Polish Jews rejected this opinion (full disclosure: I did too), and the country eventually gainedadmittance.

Twenty-five years after the fall of Communism, Poland—a NATO and EU member, a U.S. ally in Iraq and Afghanistan with a surprisingly resilient market economy and a boringly predictable democracy—has a small but thriving Jewish community, of which most Poles are justifiably proud . . . and an anti-Semitic minority that will not go away. Had we failed in our freedom bid, Poland would probably look like Belarus today—a grotesque Stalinist parody of a state that jails people for standing in the street in mute protest.

The people of Ukraine are trying to do today what we in Poland did a generation ago. If they fail, Ukraine will probably look much more like Belarus than Poland. It is not the same as choosing between Hitler and Stalin, and for Jews it cannot be an entirely comfortable choice, but it is the right one.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Distant Cousins

None of these four novels by American Jewish writers is fully at home in Israel—they’re more like Mars orbiters than rovers.

Lincoln and the Jews

Lincoln encountered a surprising number of Jews in his life. Throughout, he seems to have treated them with the benevolence and absence of prejudice one would expect from the Great Emancipator.

Fog

Every spring for the last ten years, a fog has crept over Haim Watzman's life. It begins to dissipate on Yom Hazikaron, Israel's memorial day.

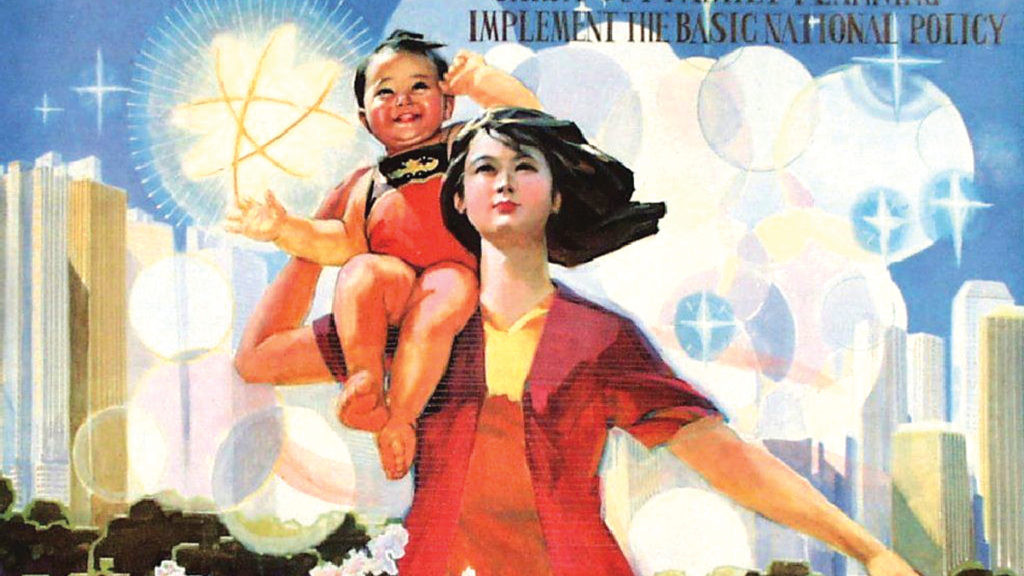

On Not Bringing Up Baby

What happens when the rising cost of raising children meets the downward pressure on reproduction?

charles.hoffman

the real Ukrainian question:

For 20 years we stood on corners in the rain and in the hot sun; we marched, we rallied, we protested, we used up the political capital of American Jewry, and we shouted ourselves horse. All in the name of letting Jews leave Russian and Ukraine.

Now that they have the opportunity, why in hell don't they just leave before they're caught up in the hell that's definitely coming their way.