Killer Backdrop

Glossy-covered, deckle-edged, carrying enthusiastic blurbs on their backs, new works of Holocaust fiction arrive regularly at the JRB offices. So many, in fact, that they have spilled off the shelves allotted to the Holocaust, forcing us to move them to the tops of several bookcases. This is more than just an issue of space; these books simply don’t belong on the same shelves as works by scholars and survivors. Perhaps this effusion of novels is to be expected. If Auschwitz can have a gift shop, why can’t the Warsaw Ghetto have a love story?

Time has disproved Adorno’s famous axiom about poetry after Auschwitz, but our familiarity with the history of the Shoah brings new urgency to critic Reinhard Baumgart’s observation that Holocaust fiction, “by removing some of the horror, commits a grave injustice against the victims.” And now we have Holocaust genre fiction, a glut of books aimed at people who apparently find romance more moving when it comes with a frisson of historical horror.

Take, for example, The Train to Warsaw by Gwen Edelman, blurbed as follows: “In this lyrical exploration of memory, there is more urgent sensuality and haunting desire than anything I’ve read in a long time.” Edelman renders the Holocaust just frightening enough to provide the dramatic tension necessary for a novel that spends as much time in the bedroom as on the streets of the Warsaw Ghetto, where Jascha and Lilka met and fell in love. Forty years later they return for the now-famous Jascha to give a reading from one of his books. Much of the novel consists of dialogue between the two:

The radiator clanked and the heat began to rise with a hiss. Lilka brought out a small chocolate cake. Is it the one I like? he asked. She nodded. With marzipan? His eyes grew shiny. Oh darling, he said. Come and sit on my lap. Let me hug you and kiss you. I’ll take you to Paris. We’ll go to Fouquet’s. I’ll buy you stockings with a black seam up the back. Like before the war. I don’t want to go to Paris, she said. Take me to Warsaw.

The radiator isn’t the only thing clanking. Here are Jascha and Lilka reminiscing:

Women were mad for me. Were they? she asked. Sometimes I brought them something we had smuggled in. A pot of jam, a hair ribbon, a few cigarettes. What a hero I was. I still had dark curls. And I could run like the wind. He smiled. What adventures we had. He smoked and flicked the ashes onto the floor. In those days, in the ghetto, long long ago, he said, I was young.

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi wrote of the Holocaust that, “I have no doubt whatever that its image is being shaped, not at the historian’s anvil, but in the novelist’s crucible.” If the novelist is Gwen Edelman, God help us all.

But it is unfair to single out Edelman. After all, even Harlequin has gotten into the Holocaust novel business. Regardless of the publisher, sex always looms large in these novels, often appearing sooner and more often than the Nazis. It is telling that almost all of the relationships in such books are illicit in one way or another. Take Far to Go, by Alison Pick. It tells the story of the romantic relationship between the Bauer family’s loyal Gentile nanny and Pavel Bauer’s duplicitous—and married—employee, a Sudeten German named Ernst who wants to “Aryanize” the Bauers’ financial assets before the Nazis get the chance. We are also witness to Pavel and his wife Anneliese’s fraying marriage and the affairs that develop between Anneliese and a German officer and between Pavel and the nanny. (Sexual relationships between Jews and Germans are common in these books; in The Train to Warsaw, Lilka’s mother is killed because of her affair—conducted inside the Warsaw Ghetto—with a Nazi officer.)

How are we to assess such fiction? The reviews of many of the higher-end novels are often glowing; Far to Go was long listed for the prestigious Man Booker Prize. In A Thousand Darknesses: Lies and Truth in Holocaust Fiction, Ruth Franklin says that, “What matters . . . is the work’s own internal dynamic: its creative ambition, its motivations.” This metric has the advantage of marrying aesthetic judgment to common sense: Why are you writing a novel set in the Holocaust? Of course there was romance in the ghettos (and the forests and even the camps), but is the author aiming at careful reconstruction or crass exploitation?

Anna Funder, author of All That I Am, may have inadvertently explained how it is possible to turn out a book about the Holocaust in which a character says (as Jascha does in Gwen Edelman’s The Train to Warsaw), “Lovemaking was never as good as when you might die in the next moment.” Funder writes (in the voice of Ruth Becker Wesemann):

[A]t a distance of seventy years, it is safe to imagine, because no one can be called on to act. No one held to account. The costume party will not be interrupted.

Historical fiction often has the feel of a costume party, and perhaps it is too much to hope that writers of Holocaust novels would be aware of the literary and moral dangers in dressing up their banal characters and plots in the clothes of Nazis and their victims.

In Funder’s case, her novel struggles to find the proper balance between historical accuracy and dramatic tension. It starts in the years when her main characters—the real-life leftist playwright and political activist Ernst Toller and Socialist writer Dora Fabian—are still living in Germany. But the reader comes away with no real understanding of the importance of either figure. Even the performance of one of the plays that put Toller on the Nazi’s enemies list is used primarily to drive forward the tortured romantic relationship between Toller and Fabian.

Hagiography does not serve history, but All That I Am veers in the opposite direction, spending page after page on the characters reveling in nightclubs that offer cocaine along with cocktails and the “entertainment” of nude models pretending to be statues. Open marriages, bisexuality, drug use, and abortion cannot be ignored in an honest history of Weimar, but here they take prurient center stage. One almost feels as if these anti-Nazi characters are being depicted through Nazi eyes.

Despite the literary and moral dangers, using the Holocaust is enticingly convenient. As Alison Pick explains in an interview printed in the back of Far to Go:

[B]y setting the book against a dramatic backdrop such as the lead-up to the Second World War, part of my work was already done. I had a series of actual events and preexisting political tensions. All I had to do was drop my characters into the scene and see how they’d react.

Pick, it should be noted, is the granddaughter of Czech Jews who fled the Nazis and settled in Canada, raising their two sons as Christians. As much as one wants to give her the benefit of the doubt, one cannot help but cringe when she says, in the same interview, that “from a marketing and publicity perspective . . . it would have been nice if the book had been out” in time to coincide with the 70th anniversary of the Czechoslovakian Kindertransport, trains that took Jewish children to the relative safety of England in 1938 and 1939. How very unfortunate for her marketing and publicity personnel that the writer couldn’t have rushed her prose or the Germans couldn’t have held off invading their neighbors for just a little bit longer.

Tone-deafness is, I think, the key to understanding how this genre came into being and how it continues to flourish. How else could an editor allow Anna Funder’s imagining of a dialogue between Ernst Toller and W.H. Auden in which Toller says, “This is a conversation we’ve had before—about the temptation of art, like fire, to use people as fuel,” to escape the red pen?

The recent booksellers’ catalog from Knopf/Vintage outlines the selling points for The Aftermath by Rhidian Brook. Due out in paperback in September 2014, the book has already been optioned for the movies by Ridley Scott—director of Blade Runner, Alien, and American Gangster. The press materials reveal that one character is based on Brook’s grandfather, “giving the novel great immediacy and emotional resonance, and very strong hooks for publicity.” A grandfather in a story in which “enmity and grief give way to passion and betrayal” against the background of Nazi genocide? Money in the bank.

Many years ago, I wrote a small textbook, aimed at seventh- to ninth-graders, on the Nuremberg laws. It isn’t a great book, but it does attempt to tell the truth, and I only stopped having nightmares a year after I finished it. One fact has stuck with me for the almost two decades since it appeared, although I have not spoken or written of it in all that time. At Treblinka, the Nazis’ victims disembarked from the train, were stripped of all their clothes and belongings, and moved directly into a fenced-in path, covered with tree branches to prevent views from inside or out, called “the tube.” This “tube” led to the gas chamber entrance, allowing a small group of Nazi guards to murder approximately 850,000 Jews and Romani between July 1942 and October 1943. No matter how efficient the camp, there were, at times, backups in the tube, when people, rather than being rushed to their death, had to wait, naked in the bitter cold, before they were murdered. The feet of the children, whose skin was softer than that of their parents, would sometimes freeze to the hard ground, and they would have to be ripped up to be moved to the gas chambers, their skin and blood sticking to the frozen earth.

If you write a novel set in the Holocaust, if you promote it, blurb it, or shill for it, and you do not know how children spent their last moments in Treblinka, or other equally terrible facts, then you should stop now. If you do know and nonetheless continue with your work, then there is probably little any of us can say.

If not today, then tomorrow or the next day, another piece of Holocaust genre fiction will arrive here in the mail. The costume party will not be interrupted.

Erika Dreifus’ response can be found here.

Amy Newman Smith’s rejoinder can be found here.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

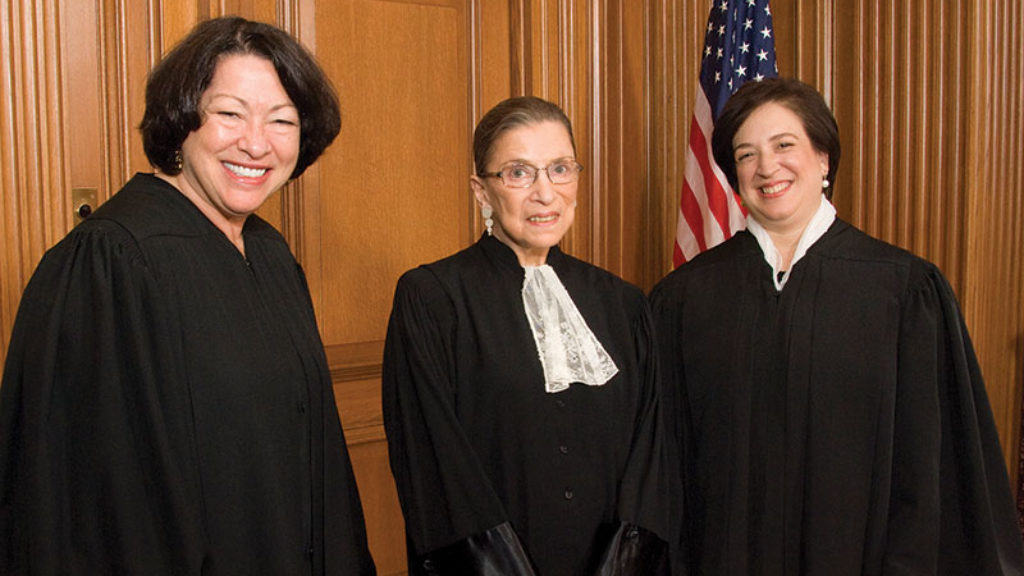

Great Jews in Robes

If Merrick Garland had been successfully confirmed for the seat now occupied by Neil Gorsuch, Jews would have been just one vote shy of constituting a majority on the court.

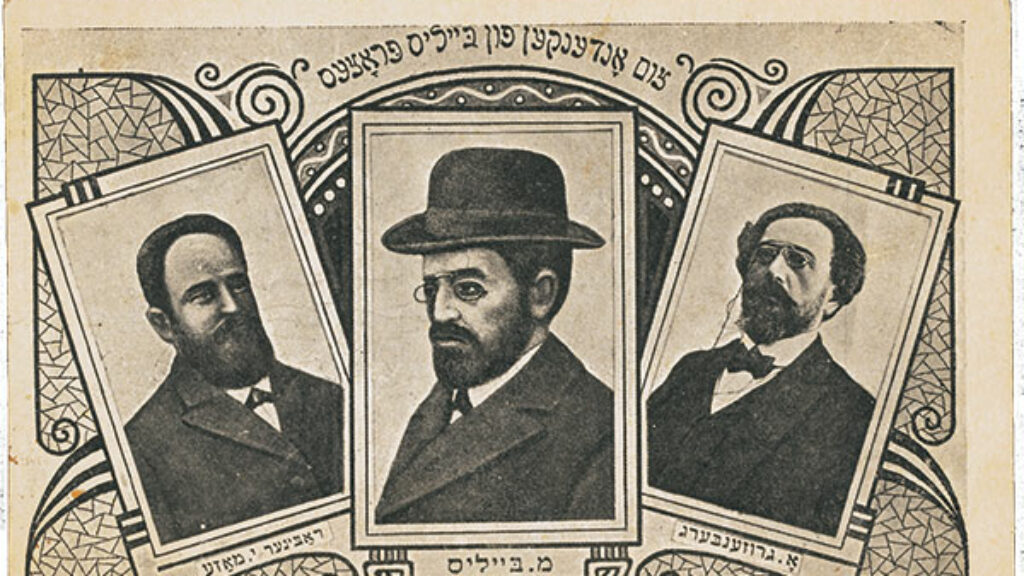

Blood Delusion

While the blood libel was rooted in Christianity, it also accused Jews of practicing precisely the opposite of what Judaism itself teaches, namely, not to consume blood.

Life on a Hilltop

City on a Hilltop is superbly researched, altogether accessible, and will dispel many lazy stereotypes about the people whose story it tells. But it leaves out a lot.

The Wages of Criticism

The great 18th-century talmudist Rabbi Aryeh Leib Ginsburg never whitewashed his disagreements with other scholars, claiming that most "ruined good paper and ink and embarrassed the Torah." According to a popular rabbinic legend, his downfall came when, in an act of cutting vengeance, the books he had criticized came toppling upon him.

dsquin

Some touches of savage indignation there, like that of Swift. And so justified.

No fiction can do justice, and we cannot bar any subject. But fiction that 'adopts' the Holocaust must be especially careful, and I think you point to what is needed in your 'tone deafness'. It surely is possible to write a 'Holocaust book' that is not tone-deaf.

jmountfort6400

It takes more than earnestness, good intentions, and purity of motive and response to keep history alive. History has many owners... not purely you. As we say in Pre-K: be a good sharer. The sharing is an end in itself... even when the other kids are going at it all wrong