And the Heart Is Forever Broken

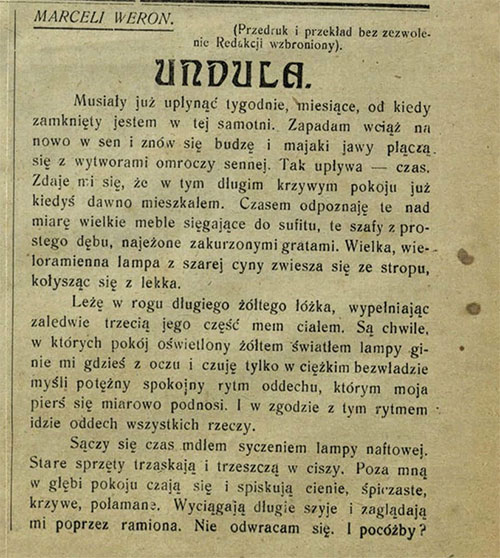

Last year, a young Ukrainian researcher stumbled on a hitherto unknown short story by the Polish Jewish writer Bruno Schulz. It appeared under a pseudonym in a most unlikely place: an oil industry newspaper called Dawn: The Journal of Petroleum Officials (Schulz’s brother, Izydor, was in the business).

“Undula,” first published in 1922 and lost for almost a century, now appears for the first time in English in the translation of Frank Garrett. The story follows a first-person narrator confined to his room. Time itself slackens through “a handful of pale squandered nights.” The story’s opening sentence reads: “It must’ve been weeks now, months, since I’ve been locked up in isolation. Over and over I sink into slumber and rouse myself anew, and real-life phantoms get jumbled up, blurring into drowsy figments.” As he watches skulking shadows “stretch out their long necks and peer over my shoulder,” Schulz’s dreamer conjures images of Undula “deliciously swooning and careening . . . in black gauze and lingerie” and fantasizes about lowering himself before her:

Through you, in the warm shiver of pleasure, I’ve come to know my misery and ugliness in the light of your perfection. How sweet it was to read from a single glance the verdict condemning me forevermore, with the most profound humility to submit to the flick of your hand that cast me from your banquet tables. I would’ve doubted your perfection should you have done otherwise.

Last November in Schulz’s hometown of Drohobych, I met Lesya Khomych, who discovered “Undula.” Finding Schulz’s literary debut came as a revelation, she said:

I thought, This is Schulz! This thought literally didn’t give me peace. I had a feeling of incredible discovery but at the same time doubts and hesitation. Could this be possible? 1922? Why [the pseudonym] Marceli Weron? I reread the story again and again. . . . The motifs and images so characteristic of his work were obvious. I confess, I pondered whether anyone else could have written this story under the influence of Schulz’s graphic works. But the convergence seemed too clear. The possibility that someone was imitating Schulz was ruled out because, at that time, his literary work was not yet known.

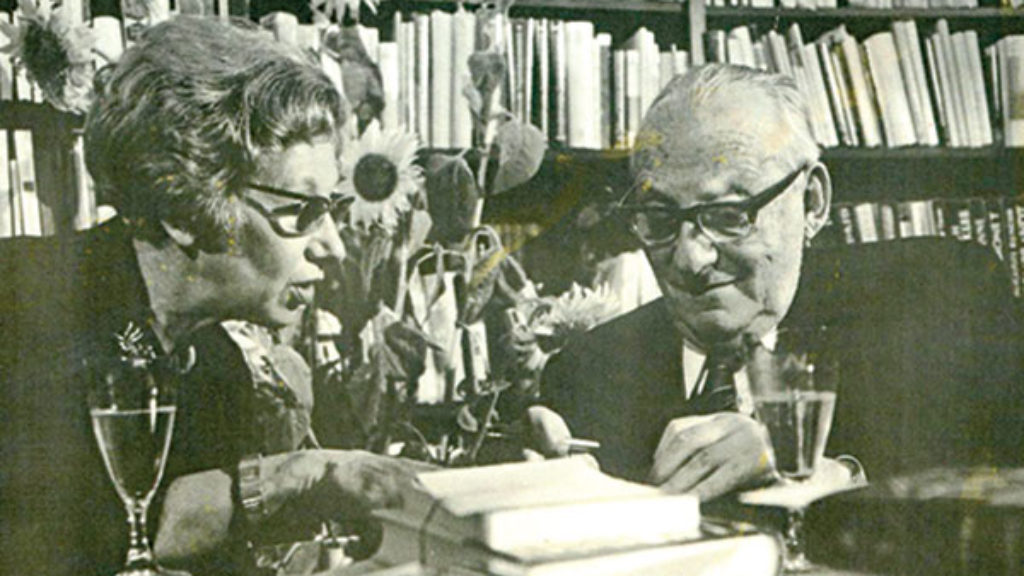

The story of how Schulz’s fiction became known begins in the summer of 1930 with a meeting between two Jewish modernists—one writing in Yiddish, the other in Polish. Bruno Schulz, 38, a self-effacing high school teacher from Drohobych, a town in Galicia, had come to Zakopane, a resort town known as the winter capital of Poland, to find “my own musical quiet, a stilled pendulum, subject to its own gravitation . . . undistracted by any foreign influence.” He cut an unobtrusive figure. A former student recalled: “He walked sloping towards the walls, obliquely, almost sidelong, with his head lowered, making way for everybody.”

The Polish artist S. I. Witkiewicz (a.k.a. Witkacy) had painted a (now lost) portrait of Schulz, giving him a fanciful fish tail. Heedless of Schulz’s wish to be free of distraction, Witkacy introduced him to the avant-garde poet and art critic Debora Vogel, 30, who had come to Zakopane to have Witkacy paint her portrait. Known as the “wandering star” of Yiddish literature, Vogel was born into a family of Galician maskilim. Her father, Anshel, was a Hebraist; her mother, Lea, was a teacher; and her uncle Marcus Ehrenpreis served as chief rabbi of Sofia, Bulgaria, and then of Stockholm, Sweden. Her wanderings had taken her to study in Vienna, Lwów, and Krakow and on frequent trips to Paris, Berlin, and Stockholm.

In the 1931 Polish census, over 80 percent of the country’s three million Jews listed Yiddish as their native tongue. Schulz was not among them; he could not read Yiddish. Yet a deep connection—intellectual and erotic—blossomed between Vogel and Schulz that summer. “Our conversations and our interactions then,” Vogel wrote to him, “were one of the rare, wonderful things that happen only once in a lifetime, perhaps only once in several hopeless, colorless lives.”

In another of her letters, Vogel alluded to the Hasidic legend of the 36 hidden righteous people who sustain the world: “We write poems and essays, we work like lamed-vovniks, and one beautiful day . . . we will discover ourselves even if nobody from the wider world comes to discover us.” Regrettably, Vogel’s writing has until now remained virtually unknown to English-language readers. With the invaluable new collection Blooming Spaces, Anastasiya Lyubas, a researcher at the University of Toronto, at last rescues Vogel from Schulz’s shadow, restores the obliterated lines of continuity between her and us, and brings Vogel the attention commensurate with the full profusion of her talents.

In translations that beautifully convey the cadences of the original, Lyubas gives us for the first time not only generous selections from Vogel’s three books but also her essays—many with a sharp polemical bite—on photomontage and literary montage, on abstract art, on the painter Marc Chagall (whom she knew personally), on racism and antisemitism (“Exoticized People”), on the role of intellectuals, and on the history of secular Yiddish writing in Galicia. The latter was a relatively young tradition “initiated,” Vogel writes, “and for a long time cultivated by, women poets who, as a rule, did not have access to the Hebrew language and the philosophy of the Talmud.”

Vogel had published her first story, “Messiah,” at age 19. The year she met Schulz, she published her first collection of free-meter poems, Day Figures, in Yiddish and had started her second, Mannequins. Her condensed painterly poems aimed, she said, at “a lyric of cool stasis and geometrical ornamentality with its monotony and rhythm of return.” Her Yiddish poems were preoccupied with shund: lowbrow literature, tacky mass culture, and kitschy commodities. One cycle of poems, called “Shoddy Ballads,” features streetwalkers, Parisian vagabonds, and—as in the following example from 1933—broken hearts and trashy novels:

And so it came about

as they write in potboilers

with invented ludicrous fates . . .

He remained forever

the best memory of her life.

Yet he was always

her life’s greatest misfortune.

Couldn’t live with him—couldn’t live without him . . .

Why did you break my heart . . .

And the heart is forever broken

as they write in cheap novels . . .

Vogel’s style reflected her vast erudition in Yiddish, Polish, German, and Hebrew. Yiddish poet and essayist Melekh Ravitch remarked:

Every word Debora writes is lined with at least three books she has read. She knew several languages, all as fluently as a native tongue. Only when it came to mame-loshn did she understand every nuance and speak it in a way that showed she was prepared to learn more and more, with great devotion and love.

“These are no artworks,” Vogel said to Ravitch of her poems, “no surface ‘experiments,’ but extracts from life and experiences for which I paid a high price.”

Those extracts offered no solace to conventional taste. Isaac Bashevis Singer recalled “that the more conservative poets mocked and mimicked her obscure style. A woman with a Ph.D. in philosophy was highly suspect in this circle.”Her poems’ austere and dispassionate coolness discomfited some readers. “I am used to being disregarded by poetic ignoramuses,” Vogel wrote to Schulz.

Moving between gravity and levity, Vogel experimented with what she called “the method of simultaneity” (simultanishkeyt), in which “cast-off, ‘small’ events receive the same importance as ‘great’ heroic life events.” Vogel called her final book, the prose collection Acacias Bloom, a montage novel. In his review, Schulz admired the way Vogel allowed human fates to be expressed only “once they pass through thousands of hearts, when they become colorless, impersonal, and representative—coins for exchange, anonymous, worn-out, and banal formulae.” In this way, Schulz adds, Vogel captures “the sound and sweetness of banality.”

A year after their meeting, Schulz proposed to Vogel. Her mother opposed the match. According to Vogel’s close friend Rachel Auerbach, “depressive, hypochondriac Schulz of course agreed with her opinion that he was not a suitable candidate for a husband and father.”

Vogel instead married a civil engineer named Shalom Barenblüth. Though Schulz occasionally stayed at the Barenblüth home in Lwów, Vogel’s relationship with Schulz continued largely by correspondence. Schulz’s letters (lost during the war), churning with self-doubt, at once seduced Vogel and kept her at a distance. (“I once lived through the writing of letters,” Schulz confessed to another woman. “At the time it was my only creativity.”) The postscripts of Schulz’s letters to Vogel—fantasies of Drohobych through the eyes of a child—grew more fantastical and unmoored from the letters’ contents, like figures in a Chagall painting floating above rooftops. Their long, eddying sentences were inlaid with metaphor. Vogel showed them to Rachel Auerbach, who insisted they be published. Thus encouraged, Schulz transformed the postscripts into a collection of short stories called The Cinnamon Shops and Other Stories, a book addressed in intimacy to a single reader—Vogel. As he wrote to Witkacy: “Somehow the ‘stories’ are true, they represent my manner of life, my particular fate. The dominant feature of this fate is a deep loneliness, isolation from the affairs of everyday life.”

The interlaced stories in Cinnamon Shops and Schulz’s second book, Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass, revolve around Father, a harried cloth merchant who in failing health “floated eternally on the periphery of life”and “waged war on the boundless element of boredom stupefying our city”by breeding birds—an extravagant collection of peacocks, pheasants, and pelicans—in the attic. (Vogel in German means “bird.”)

The father-fixated sensitive son Joseph narrates the stories, in effect telling the story of his own birth as an artist. Seeking escape from the tedium of daily life, Joseph plunges into an imaginary and still formless world of his own making, yields to the pleasure of finding the hidden life in inanimate things—like mannequins—and endows that life with an opulent mythology, a primordial power, and an almost kabbalistic account of the possibilities latent in mere matter.

Born as citizens of a province of the moribund Habsburg Empire, Schulz and Vogel would—without moving—become subjects of the West Ukrainian People’s Republic, the Second Republic of Poland (1918–1939), the USSR (September 1939–July 1940), and finally the Third Reich. Their lives, begun under the banner of the Austro-Hungarian double-headed eagle, would end in the bloodlands.

In November 1941, Schulz was forced to move into the Drohobych Ghetto. He parceled out his manuscripts and drawings to people he described in a letter only as “Catholics outside the ghetto.” One of the parcels held Schulz’s unfinished masterpiece, a novel called The Messiah, which to this day has yet to be found. In August 1942, Debora Vogel was one of 15,000 Jews murdered by Nazis during the liquidation of the Lwów Ghetto, alongside her husband, Shalom, their six-year-old son, Asher, and her mother. Meanwhile, despite his premonitions, Schulz remained reluctant to leave Drohobych. Friends in Warsaw sent him forged “Aryan” papers and prevailed upon him to set a date for his escape: November 19, 1942.

In Schulz’s story “The Age of Genius,” Joseph imagines the arrival of the messiah:

On such a day the Messiah approaches the very edge of the horizon and from there looks down at the earth. And when he sees it so white and silent, with its azures and pensiveness, it can happen that in his eyes it loses its boundary, the bluish bands of clouds lie down to form a passageway, and, not knowing himself what he is doing, he descends to earth. And in its reverie the earth will not even notice the one who has descended onto its paths, and people will awaken from their afternoon naps and remember nothing. The entire story will be as if it had been blotted out and it will be as it was in primeval times, before history began.

The savior would not arrive in time. Just before noon on November 19—the very day Schulz had planned to flee—he was shot in the head during one of the Gestapo’s so-called wild actions in Drohobych, not a hundred feet from the house where he was born. His blood soaked into a loaf of bread he had just bought. He was 50 years old.

“If Schulz had been allowed to live out his life,” Singer said, “he might have given us untold treasures, but what he did in his short life was enough to make him one of the most remarkable writers who ever lived.”

During their lifetimes and since, the fates of Vogel and Schulz diverged. Vogel had always felt hemmed in by a double marginalization: her choice of Yiddish put her outside European avant-garde circles, and her choice of avant-garde idioms and imagery cast her outside the sphere of most Yiddish writers and readers. Her writing has also been unjustly eclipsed by her relationship with Schulz, as though she were no more than a muse, a midwife to his creativity. Schulz, by contrast, has exerted an enduring fascination. “In the circles of young Polish poets to which I belonged in the late 1930s,” the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz recalled, “Schulz’s name was surrounded by a special, magical aura.”

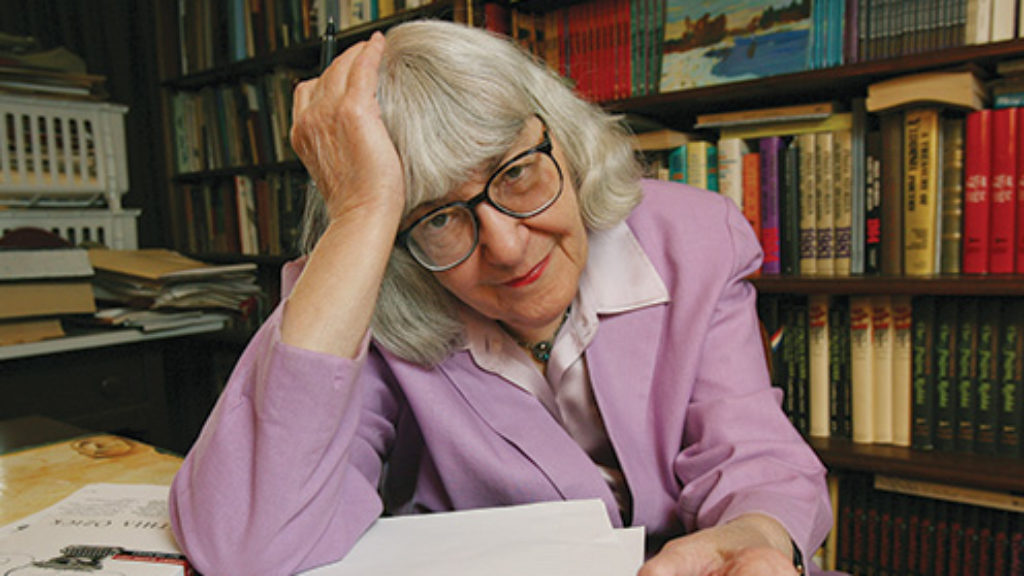

“Under the imaginary table that separates me from my readers,” Schulz’s narrator asks in one of his stories, “don’t we secretly clasp each other’s hands?” In America, Schulz clasped hands with even more readers than in his native country and has become an object of veneration for a procession of writers—including Philip Roth, Cynthia Ozick, and Jonathan Safran Foer—who came under the sway of his private mythology. Ozick, whose 1987 novel The Messiah of Stockholm is an exhilarating homage to Schulz and his lost messiah, counted him “among those writers who break our eyes with torches.”

Amid the ferment of interwar Poland, two opposite motions guided Jews who followed the sometimes blinding torches that lit the way toward modern culture. The first impulse, Bruno Schulz’s, surged outward toward an almost sublime mastery of Polish, sometimes with self-assertion and sometimes with worshipful self-abasement vis-à-vis an idealized majority culture. The second, Vogel’s, traveled inward to find ways of importing the innovations of European modernism into a newly unfettered Yiddish. Each was tragically truncated. That they met at all is no small wonder.

Suggested Reading

Something Off

There was a sense of oddness about Bruno Shulz that German-Jewish writer Maxim Biller exploits in his new novella, Inside the Head of Bruno Schulz.

Cynthia Ozick: Or, Immortality

Ozick is as marvelously demanding, harrumphing, and uncompromising as she has always been.

Lost from the Start: Kafka on Spinoza Street

Jerusalem-based writer Benjamin Balint has crafted a wise and eloquent study of Kafka around the eight-year battle in Israeli courts over Max Brod’s literary estate.

Jews on the Loose

If fame is when everyone understands it is you when only your first name is mentioned, Groucho (Marx) certainly qualifies.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In