The Essence of Dignity

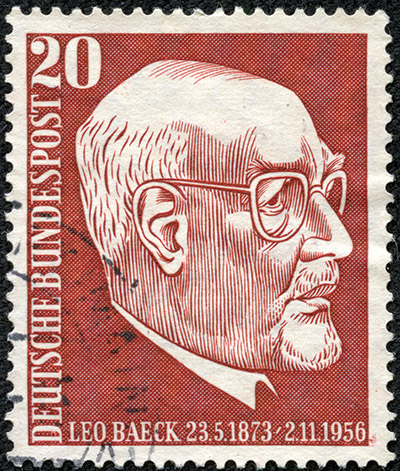

On Shabbos Nachamu in 1935, shortly before the Nuremberg Laws were promulgated, Rabbi Leo Baeck sent out a message of comfort to all Jewish communities and regional organizations throughout Germany, to be read publicly before Shabbat services:

“Comfort, oh comfort, My People” [Isaiah 40:1]. That is what today’s Sabbath calls to us. From whence in these days when we are forced to traverse a flood of insults shall comfort arise? It arises from the answer that our faith, that our honor, that our youth give us.

Against all insults, we set the majestic dignity of our religion, [against] all offenses our steady persistence in pursuing the paths of our Judaism, in following its commandments.

True honor is what each person grants to himself; he gives it to himself through a life that is unimpeachable and pure, modest and honest, as well as through a life of that self-control which is the mark of inner strength. Our honor is our honor before God; it alone will endure.

In emphasizing the virtues of self-control, modesty, and dignity while refusing to bow before a cruel and illegitimate regime, Baeck’s message exemplified both his own character and his consistent policy of prudent resistance against the Nazis coupled with pastoral care for his fellow Jews.

Michael A. Meyer’s important book is precisely the sort of biography Leo Baeck (1873–1956) would have wished for and a tribute to the German Jewish culture from which he emerged. The book presents and also mirrors Baeck’s character: deeply learned, formal, modest, and even austere. We learn the contours of Baeck’s life, his wide-ranging interests and contributions as a rabbi and scholar, and we come away with a strong sense of him as a figure of enormous dignity and decorum. Yet beneath his stately formality was a man who did not hesitate to passionately defend Judaism against its Christian critics, who boldly formulated his understanding of liberal Judaism, and who served as a wise, caring rabbi and an astute leader of Germany’s Jewish community under horrific circumstances.

Leo Baeck was born and raised in Posen, which gave us a remarkable number of brilliant rabbis and scholars over the centuries. Baeck, who attended a first-rate academic high school that was open, fortunately, to Jewish students, benefited from an extraordinary education in Western civilization and graduated first in his class. His father, a rabbi, trained him thoroughly in rabbinic texts and traditional Jewish practice. One of eleven children, Baeck was the son who followed in his father’s footsteps to become a rabbi.

His formal rabbinic training started in 1891 when, at age seventeen, he entered the rabbinical seminary in Breslau, which combined the atmosphere of a yeshiva with the rigorous study of history and historical method. The great historian Heinrich Graetz was one of his teachers. After two years, he transferred to Berlin, where he studied at the liberal rabbinical seminary Lehranstalt für die Wissenchaft des Judentums (Institute for the Scholarly Study of Judaism). Meyer suggests three reasons for the move, each revealing of Baeck’s character and subsequent career. First, Meyer speculates, he may have felt constrained by the relative orthodoxy of the Breslau institute, which, for instance, frowned upon biblical criticism. Second, he wanted to study at the prestigious University of Berlin. Third, as Meyer writes:

As would become characteristic of Baeck, he may have chosen to attend more than a single seminary, since he did not want his approach to Judaism to rest within but one of the channels in which Judaism then flowed in Germany. . . . While a student in Berlin, he supplemented his studies at the Lehranstalt with courses at a yeshiva run by a local Orthodox rabbi.

Even before he arrived in Berlin, Baeck’s breadth of knowledge was remarkable, exemplifying the German Jewish goal of Bildung (roughly, learning as self-cultivation). He read classical Hebrew, Greek, and Latin texts; knew the history of philosophy, literature, art, and religious thought; was at home in all genres of Jewish classics—biblical, rabbinic, philosophical, and kabbalistic; and also followed the writings of contemporary Christian theologians, especially on antiquity.

The early twentieth century was still the era of deeply learned sermons in liberal synagogues, and as a young rabbi, Baeck brought all of his knowledge to bear on the sermons that he carefully crafted and memorized. Nonetheless, in the towns where he first served as a rabbi, Oppeln and Düsseldorf, Baeck’s sermons were not very successful. “He was not a dynamic preacher: his sermons lacked the sentimentality that worshipers expected; and, with his soft voice vibrating disconcertingly he eschewed every popular rhetorical device,” Meyer writes. Yet they were certainly admired from afar and brought him the good fortune to be hired by Berlin’s Jewish community in 1912. Beneath his formal bearing—Meyer tells us Baeck almost always wore a three-piece suit—was a pastor who cared for souls and was remembered for his kindness as a chaplain to injured German soldiers during the First World War.

Meyer emphasizes that Baeck held a very clear commitment to reconcile differences and respect all elements and expressions of Jewish life. Thus, he wanted Jews to feel comfortable in both liberal and Orthodox communities; he wanted Jews to know Judaism and also immerse themselves in studying the great works of Western culture. When most of the Jews in Munich rejected Theodor Herzl’s ultimately unsuccessful attempt to hold the first Zionist Congress there, Baeck, a young rabbi in Oppeln, refused to join his fellow rabbis in a resolution condemning Zionism because he hoped to foster “mutual tolerance among rabbis of differing views.”

Baeck was liberal in the classical sense of being tolerant and open and seeking alliances. Theologically, Baeck believed that revelation was of moral principles, not ritual commandments, yet he also believed that the commandments serve as a protective fence around Judaism—as long as they retained their meaning. That he was generally respected by Orthodox as well as liberal rabbis, Zionists, and anti-Zionists was due both to Baeck’s personal integrity and his efforts to avoid political divisiveness. Yet he did not compromise his beliefs. He was courageous, supporting mixed seating of women and men in the synagogue at a time when that was almost unheard of, even in Reform synagogues in Germany. With his signature, he also certified the ordination of Regina Jonas, who in December 1935 became the first female rabbi. Jonas and Baeck worked together in Berlin and later in the ghetto camp Theresienstadt, from which she was deported and murdered at Auschwitz in 1944.

While still a young rabbi in Oppeln, Baeck took on one of the most important professors of Protestant theology in the German academy, Adolf von Harnack, whose book Das Wesen des Christentums (The Essence of Christianity) had become an internationally acclaimed bestseller in 1901 and a classic statement of liberal Protestantism. However reserved Baeck was with his congregants and even his own family, he could be fearless in print in defense of Judaism. As Baeck boldly argued, Harnack’s presentation of Jesus ultimately rested on a thoroughgoing denigration of Judaism. While Harnack acknowledged that Jesus’s teachings were anticipated by the prophets and rabbis of his day, he argued that the Gospels were superior because they were untainted by the perverted ritualism of ancient Judaism. With the rabbis, Harnack wrote:

[Religion] was weighted, darkened, distorted, rendered ineffective and deprived of its force, by a thousand things which they also held to be religious and every whit as important as mercy and judgment. . . . The spring of holiness . . . was choked with sand and dirt, and its water was polluted.

With Jesus, “the spring burst forth afresh, and broke a new way for itself through the rubbish.” For Harnack, then, it does not matter that Jesus’s teaching was unoriginal but that, unlike Judaism, it was pristine, a pure spring rather than muddy water.

Baeck expanded his negative review of Harnack into his own book, Das Wesen des Judentums (The Essence of Judaism), and continued the argument in his classic article, “Romantic Religion,” published in 1922. In this sharp, sustained polemic, Baeck argued that Christianity had chosen to follow Paul and thus violate Jesus’s own adherence to the law. This turned Christianity, in Baeck’s words, into a “romantic religion” of mysticism in which human beings remain trapped by their sinful nature, passively awaiting salvation through grace:

In this ecstatic abandonment, which wants so much to be seized and embraced and would like to pass away in the roaring ocean of the world, the distinctive character of romantic religion stands revealed—the feminine trait that marks it. There is something passive about its piety; it feels so touchingly helpless and weary, it wants to be seized and inspired from above, embraced by a flood of grace which should descend upon it to consecrate it and possess it—a will-less instrument of the wondrous ways of God.

Feminine Christianity, Baeck argued, fails to foster moral responsibility, in contrast with the masculine “classical religion” of Judaism, which places ethical commandments at the forefront and, unlike Christianity, rejects belief in nonrational doctrine.

Beck moved from Oppeln to Düsseldorf in 1907, where he met Eastern European Jews as well as German Jews with little interest in religious practice. In searching for new ways to make Judaism appealing, he wanted to find a middle path between affirming that Western culture was not simply the province of Christianity and insisting on the distinctiveness of Judaism and its nonconformity. In 1912, just two years before the outbreak of war, Baeck moved to Berlin, where he had a far more sophisticated community to serve and also the chance to teach at the Lehranstalt. Yet within weeks of the outbreak of war, Baeck became one of the first six rabbis to serve as chaplain to the German army. Caring for soldiers was his goal; the raging jingoism in Germany did not infect him. For Baeck, nationalism was “national egoism,” and war could be justified only on the basis of justice. As a chaplain, his work included leading huge Passover Seders, serving the impoverished Jewish population in the east, and conducting funerals, including mass burials of soldiers. As would often happen in his career, he was selected by his peers—in this case, his fellow chaplains—as their leader.

What emerged from Baeck’s wartime experience was an affirmation that the ideals of Prussia were represented not by militarism but by the spirit of the German Enlightenment, epitomized, in particular, by Gotthold Lessing. Moreover, the Enlightenment’s central idea of universal morality was “largely born from the spirit of Judaism,” and it was precisely this idea that had brought about the emancipation of the Jews over the last century.

After World War I, Berlin saw an explosion of creativity in nearly every aspect of the arts and sciences, literature, music, and scholarship. Weimar Berlin was also a major center of Jewish life that included more than 170,000 Jews, a third of the Jewish population in Germany. Creativity and intellectual experimentation abounded. New ways of understanding the human condition reached Baeck in his explorations of religious experience. If Jews in the Weimar Republic underwent a renaissance, as historian Michael Brenner has argued, Leo Baeck was its conservative representative, a figure of noble bearing who embodied the greatness of German Judaism’s heritage, a liberal rabbi yet observant of Jewish law. Tradition was important to him, but he also believed that Jewish rituals must express religious ideas and values that “transform all existence into religious service.”

While Baeck is less known for his scholarship than for his work as a pastor and communal leader, his publications, presented with exceptional clarity by Meyer, reveal a scholar who rebelled against conventional scholarly methods and topics, seeking a more engaged approach that would understand religion from within. That engagement, replacing the distant scholar seeking pure objectivity, permeated the Weimar era, and Baeck, like many of his contemporaries, was influenced by the philosopher Wilhelm Dilthey’s argument that a proper hermeneutical, or interpretive, understanding of a text or historic moment always involved a kind of empathy.

Through his friendship with several intellectual members of the German nobility, he also came to know Count Hermann von Keyserling and participate in his “School of Wisdom,” which held public lectures and conferences from 1920 to 1927, delivered by some of the most interesting intellectuals from many fields. Keyserling was promoting a “therapeutic orientalism” that drew on neoromantic readings of Indian and Chinese religions. This was a pivotal moment for intellectuals in Germany, as some went from this romanticism to racism and even, eventually, Nazism. In the three lectures Baeck delivered at Keyserling’s gatherings, some orientalist influences are apparent in his depictions of religiosity, yet he firmly asserted Judaism’s important balance of spiritual subjectivity with ethical principles and actions. For Baeck, Christianity, not Judaism, exemplified romantic orientalism because it lacked the firm ethical foundation of Judaism.

Whereas many, if not most, of the rabbis who created liberal Judaism in Germany focused their scholarship on rabbinic-era Judaism or medieval Jewish philosophy, seeking precedents for their reforms, Baeck was undeterred by kabbalistic texts. His studies included important work on Sefer yetzirah and Sefer bahir, works that had only just begun to come to the attention of scholars of Judaism. Here he drew from his father and expanded his approach. Samuel Baeck had published a five-hundred-page survey of Jewish history in 1878 that included translations of passages from the Zohar and a discussion of Lurianic mysticism, writing that Kabbalah brought to the mitzvot “true consecration and holy virtue.”

Conceptual contrasts mark Baeck’s writings—Judaism and Christianity, Judaism and Greek thought, men and women, mystery and commandment, death and rebirth, spirit and blood, perfection and tension—reflecting his efforts to avoid a dogmatic approach and seek reconciliation by understanding both sides. From his father’s admiration for Kabbalah and from the growing movement of romantic orientalism came his emphasis on personal, subjective religious experience. Nonetheless, the 1922 edition of his Das Wesen des Judentums emphasizes that Judaism is a religion of ethics and that God stands as the ultimate ground of moral imperative. Still, Baeck understood that there is mystery beyond the commandments of Judaism, and that mystery is God.

Over the course of the 1930s, half the Jews of Germany were able to emigrate, and those left behind were increasingly elderly, ill, impoverished, and in dire need of assistance.

Until the very last moment, Baeck had ample opportunity to leave Germany. His wife, Natalie, died in March 1937, and shortly after, his only daughter, Ruth, left Germany with her husband and daughter for England. No one would have blamed him had he followed her. And yet he stayed to serve the remaining Jewish community and was elected president of the Reichsvertretung der Deutschen Juden, the communal organization for besieged German Jewry. Baeck’s good deeds did not go unpunished; he struggled with ugly, arrogant opposition from some Jewish lay leaders in Berlin who consistently sought to undermine him and acted with seemingly determined unethical behavior. He was similarly appalled at Theresienstadt by the vulgar and even cruel behavior of some of the Jews appointed to “leadership” positions, Meyer tells us. Although he was almost universally, and in my view correctly, hailed as a moral hero after the Holocaust, occasional accusations that Baeck’s dealings with the Nazis were sometimes too accommodating, and his stance toward his fellow Jews sometimes too paternalistic, have shadowed his reputation. Philosopher Hannah Arendt rather infamously described him as the “Jewish Führer” for his leadership roles under Nazi Germany. Most recently, the Czech historian Anna Hájková has subjected Baeck to harsh criticism for failing to inform Jews in Berlin and, later, in Theresienstadt of the death that was almost certainly coming.

Meyer carefully delineates the circumstances and explains Baeck’s efforts to tread firmly but cautiously. Most important for Baeck were not acts of physical opposition to the Nazis but preserving Jewish lives. In May 1942, Baeck witnessed the revenge taken by the Nazis after the Herbert Baum Communist resistance group set fire to an antisocialist exhibit: 250 Jews were shot; 250 Jews were deported. Baeck himself was arrested briefly five times; that he survived demonstrates he was a shrewd and politically sharp tactician who deliberately, and with great courage, presented himself to Nazi officials as a self-possessed man of dignity—precisely the opposite of Nazi propaganda images of Jews. It is nonetheless true that as a leader, Baeck was put in the position of having to make extremely difficult decisions.

Shortly after the outbreak of mass deportations of Jews in October 1941, Baeck learned that some, and perhaps most, of those being sent “to the east” were in fact being murdered in gas vans, but he hesitated to tell his fellow Jews. He was not in charge of selecting Jews for deportation, but he did arrange for them to be assisted compassionately by rabbinical students and other volunteers when they were ordered to report to the Gestapo. Emigration from Germany was no longer possible, but some Jews found hiding places with Gentile friends, particularly in the Berlin area. One of these was a student of Baeck’s, Herbert Strauss, whom Baeck did not tell of the fate that awaited Jews deported east, even after he went into hiding. “Would his making public what awaited us in Eastern Europe have saved lives, even if it would have cost him his own?” The question was sincere—Strauss had loved Baeck as a teacher—and yet it seems clear that, even if Baeck was wrong to have kept quiet, his concern was not for himself.

On January 27, 1943, Baeck was deported from Berlin to Theresienstadt, where he was imprisoned throughout the war and remained several months after the Russians arrived on May 10, 1945, assisting the now-liberated remaining prisoners. At Theresienstadt, Baeck served on the so-called Council of Elders, but he was not head of the Jewish administration that selected individuals for deportation. As a rabbi, Baeck delivered eulogies, performed weddings, counseled the despairing, and joined the project of giving lectures in the evenings. Meyer reports that at least 2,430 lectures were delivered by 520 speakers, and they were one of the great sources of spiritual sustenance for the prisoners. Baeck is estimated to have delivered lectures on thirty-eight topics, only one text of which survives. Baeck’s earlier difficulties as a sermonizer were now gone; his talks were called “wise and brilliant” and “models of crystal-clear exposition.” One inmate, Ruth Klüger, later wrote that Baeck “gave us back our heritage.”

At Theresienstadt, Baeck became close to the distinguished Prague intellectual H. G. Adler, a prisoner who later wrote the great study of the camp. When Adler was deported to Auschwitz with his wife and her mother in October 1944, it was Baeck who preserved his careful documentation, at risk to his own life. By then, Baeck was in his seventies, living in extremely difficult circumstances, though he was given some privileges, including a two-room apartment, by Nazi officials who recognized his important symbolic status as representative of the Jewish community to the Nazi Reich. (His non-Jewish housekeeper from Berlin came to care for him in the ghetto.)

Baeck had become aware of the death camps by August 1943. Meyer reports a postwar discussion Baeck had with a survivor of Auschwitz in whom he confided his pangs of conscience. Had he informed the prisoners that murder awaited those deported, would they have staged a physical revolt that surely would have ended in death—though perhaps a few might have escaped and survived? What of the despair and increased suicides among the prisoners? And the revenge of the Nazis if prisoners escaped or rebellion occurred? Meyer writes that this was a “dilemma where moral arguments could be made for either side,” and surely this is true.

In addition to leading the Jewish community of Berlin in the 1930s, Baeck wrote an extraordinarily long book, 1,245 pages in manuscript, surveying the legal position of Jews in European history. It is not clear whether Baeck wrote the book, which remains unpublished, on behalf of the Resistance, as he once seemed to imply after the war, or at the demand of the Gestapo. Meyer tends to think that Baeck, at least ostensibly, undertook the project at the behest of the Gestapo, in part because he was given access to the archives of the Prussian state library. And yet, Meyer notes that nothing in the book would have served the Gestapo’s purposes. (A forthcoming book by Yaniv Feller will analyze the text and its provenance.)

Baeck’s heroism in not abandoning the Jewish community was recognized with honors after the war. In 1955, he published the first part of his final book, This People Israel: The Meaning of Jewish Existence, a history of the Jewish spirit. He lectured around the world, and his voice carried enormous moral weight. He also reconsidered some of his earliest arguments and views, including his understanding of Christianity, which he came to view not as Judaism’s opposite but as a religious tradition standing in a common hope and heritage.

Baeck died in November 1956 in London, where his daughter and her family were living. The noble bearing of this wise, learned, gentle rabbi symbolizes the grandeur of German Jewry. His guidance of the Jewish community in terrible political circumstances and his ability to stand up to both the Nazis and Jewish establishment figures remains a moral example to us today.

Michael A. Meyer, who was born in Nazi Germany, is the preeminent historian of German Jewry. He has given us a biography of the kind of person we might all strive to emulate. The book is beautifully crafted, carefully weighing complex historic circumstances and shrewd biographical judgments, always remaining faithful to the very fine character of its subject.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Witness

Raised in an assimilated German-speaking family and baptized as a Protestant at age 12, Adler had seemed destined for a stellar literary career as an heir to the Prague Circle, a group of German-language writers that included Kafka, Max Brod, and the philosopher Hugo Bergmann. His imprisonment in Theresienstadt changed the arc of his career and gave us some of the most powerful testimony about the inner life of the camps that has ever been written.

A Brand Rescued from the Fire

Leon Chameides has painstakingly collected his father’s writings from the fateful years of 1930s Polish Jewry, before the break-up of his family and the collapse of Jewish life in Nazi Europe.

Eichmann, Arendt, and “The Banality of Evil”

Richard Wolin’s review of a new book about Adolf Eichmann caused a stir, mainly about Arendt. His exchange with Seyla Benhabib on the banality (or not) of evil.

The Gray Lady and the Jewish State

Jerold Auerbach’s archly titled new study Print to Fit: The New York Times, Zionism and Israel, 1896–2016 is a well-researched and, for the most part, damning brief of the Times’s news coverage and editorial attitudes toward Zionism and Israel for over a century.

SMF

"His guidance of the Jewish community in terrible political circumstances and his ability to stand up to both the Nazis and Jewish establishment figures remains a moral example to us today." ??? You must be joking. At least you note, "Philosopher Hannah Arendt...described him as the “Jewish Führer” for his leadership roles under Nazi Germany. Most recently, the Czech historian Anna Hájková has subjected Baeck to harsh criticism for failing to inform Jews in Berlin and, later, in Theresienstadt of the death that was almost certainly coming...Shortly after the outbreak of mass deportations of Jews in October 1941, Baeck learned that some, and perhaps most, of those being sent “to the east” were in fact being murdered in gas vans, but he hesitated to tell his fellow Jews...he was given some privileges, including a two-room apartment, by Nazi officials who recognized his important symbolic status as representative of the Jewish community to the Nazi Reich." With such so called leaders, who needs enemies? Baeck was an idiot who furthered the means and ends of the Nazis in the Holocaust. With leaders such as Baeck, there would have been no Warsaw Ghetto, no State of Israel. Compare his actions to those of such leaders as Jabotinsky. Baeck is symbolic of all that was wrong with German Jewish leadership in the decades leading up to the Holocaust. Spare us all from apologists for such people.

Steven Aftergood

This is a vulgar and ignorant comment that would not survive a reading of the book that is under review. Hannah Arendt retracted her "Jewish Führer" remark and it no longer appears in current editions of her Eichmann in Jerusalem book. In fact, in a 1968 interview cited by Meyer, Arendt praised Baeck for his "unquestionable courage and disregard for personal danger." Why would she have done this? Maybe you should read the book.