These Heroic Girls

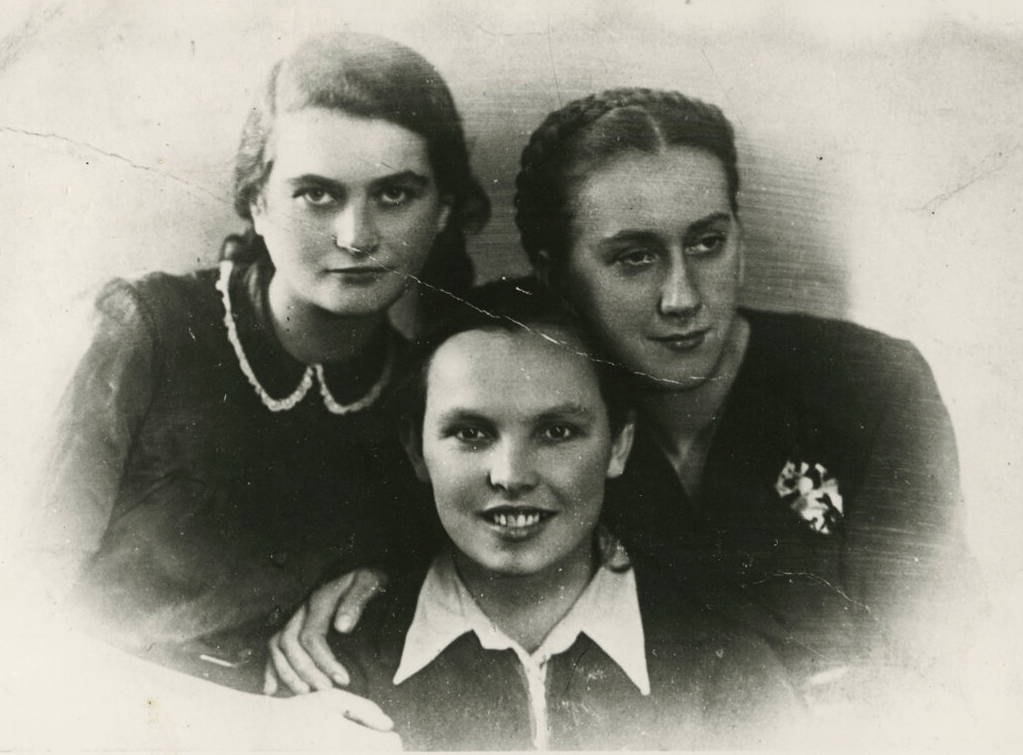

During a wartime Christmas party, three young Polish women pose for the camera. The photograph seems to capture a carefree moment in their lives, but look more closely, and you can see the subtle tension in their faces. On that December night in 1941, these three young Jews, Tema Schneiderman, Bela Hazan, and Lonka Kozibrodska, were spending the evening in the company of Nazis at the Grodno Gestapo headquarters under assumed identities, secretly gathering intelligence on behalf of the underground Jewish resistance.

Judy Batalion learned of these and other brave “ghetto girls” twelve years ago in London when she was researching Hannah Senesh and came across Freuen in di Ghettos, a 185-page anthology featuring the stories and testimonies of female resistance fighters from across Europe. These young women were utterly fearless:

[They] paid off Gestapo guards, hid revolvers in loaves of bread, and helped build systems of underground bunkers. They flirted with Nazis. . . . They carried out espionage missions. . . . They . . . upheld group morale.

The key contributor to Freuen was Renia Kukielka, who jumped off a moving train to avoid Nazi detection when she was eighteen and who spent the war years as a courier smuggling weapons and secret communications between Jewish resistance groups across Poland.

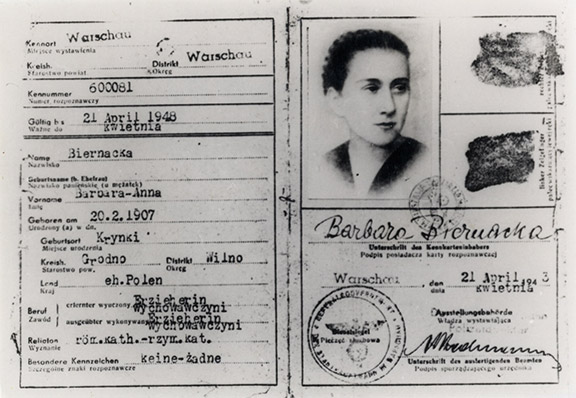

Brave young women like Renia, Bela, Tema, and Lonka carried out a variety of missions for the resistance. Some were couriers (called Kashariyot) posing as Polish working girls while they smuggled money, weapons, and subversive literature between ghettos and underground Jewish cells. Others, like Vladka Meed, assisted Jews in hiding throughout Warsaw. Many of the women took up arms in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, including the famed Zivia Lubetkin, who was a leader in the Dror youth movement. (A number of these young women had been committed members of Zionist youth groups before the war. Through these groups, the young women channeled their ideological zeal and developed tremendous physical and psychological fortitude.) Outside the cities, Jewish women were active with several partisan units; Faye Schulman, for instance, was a photographer-turned-nurse who operated on partisan fighters without anesthetic or proper training.

Other women worked alone. Niuta Teitelbaum, a communist in her midtwenties, wore beautiful braids that complemented her doll-like face and served as “an innocent disguise that hid her role as an assassin”:

[In one operation], she killed two Gestapo agents and wounded a third who was taken to the hospital. Niuta, disguising herself as a doctor, entered his room, and mowed down both him and his guard. . . . In another instance, she strolled up to the guards outside Szucha, feigned shame, and whispered that she needed to speak to a certain officer about a “personal matter.” . . . In her “boyfriend’s office,” she pulled out a concealed pistol with a silencer and shot him in the head. On the way out, she smiled meekly at the guards who’d let her in.

Teitelbaum was eventually caught, tortured, and murdered by the Gestapo at age twenty-five.

Batalion’s women also faced dangers within the ghettos, specifically from the Ghetto Judenrat (Jewish councils) and their Jewish police forces. Throughout The Light of Days, Batalion depicts these Jews as unrepentant collaborators with the Nazis, rather than compromised individuals often attempting to do their best under impossible circumstances. Though she qualifies her position early on in the book(“the subjective will of their many individual members varied”), overall it is a sharp indictment of Jewish councils’ role in the persecution, deportation, and even murder of their fellow Polish Jews. Batalion highlights the assassinations of Judenrat officials and Jewish policemen at the hands of Jewish fighters in the ghetto, but she leaves the profound ethical questions of both these killings and the actions of their victims largely unexplored.

Although Batalion’s work mainly focuses on the network of the Kashariyot and female ghetto fighters, her history also exposes the often-overlooked resistance of Jewish women in Gestapo prisons and concentration camps. After Anna Heilman, a Warsaw Young Guard member, arrived in Auschwitz, she and other women played a crucial role in procuring gunpowder for the uprising of the Sonderkommando (Jews forced to work in the gas chambers and crematoria)at Auschwitz in October 1944. Several hundred prisoners were killed in the rebellion, and four women were tortured and executed for their involvement.

It ultimately seems unthinkable that the heroism of such women has been almost entirely overlooked until now. Why were their narratives lost? Why did Renia’s Freuen disappear from our collective consciousness? The answer, as Batalion demonstrates, is not a simple one. Renia ultimately survived torture and imprisonment, escaping to Israel in a death-defying trek through the mountains of Slovakia. In Israel, she was met with relative indifference from the sabras, who saw weakness, not profound courage, in the survivors. “We feel like we’re smaller and weaker than the people around us,” Renia wrote shortly after arriving in Israel. “Like we don’t have the same right to life as they do.”

Other former female fighters felt similarly marginalized and unmoored in their surroundings. Though these women were ardently Zionist, and much of their resistance activity was driven by their desire to reach the Jewish state, they often battled loneliness and depression in Israel. Chajka Klinger, a fighter who took command of the uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto, had written exuberantly of the resistance: “The first shot. I am so proud. I am so happy.” She only lived to age forty-two.

On the fifteenth anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, Chajka Klinger hung herself from a tree, not far from the kibbutz nursery where her three sons played. Not everyone survives surviving.

Four years after Tema, Bela, and Lonka were captured in that infamous photograph at the Gestapo Christmas party, the war ended. Only Bela and the photograph made it through the Holocaust.

Tema was murdered in the Warsaw Ghetto during the first uprising in January 1943. Bela and Lonka were arrested and tortured by the Gestapo. Lonka died in Auschwitz, cared for by Bela to the end. Bela made it to the American side of postwar Germany and from there to Israel, where she published her memoirs, raised a large family, and dedicated her life to volunteering with the sick. She had kept the photograph and “placed this heirloom next to her bed, where it stood for the rest of her life.”

In 1942, the famed Jewish historian Emanuel Ringelblum (leader of the Oyneg Shabesin the Warsaw Ghetto) wrote about the young Jewish resistance fighters:

These heroic girls . . . they are a theme that calls for the pen of a great writer. How many times have they looked death in the eyes? . . . The story of the Jewish woman will be a glorious page in the history of Jewry during the present war. And [ these women] will be the leading figures in this story. For these girls are indefatigable.

Until now, Ringelblum’s prophecy remained unfulfilled; the heroic girls were largely nameless and forgotten. But in The Light of Days, Batalion rectifies this historical wrong.

Suggested Reading

Du Bois, the Warsaw Ghetto, and a Priestly Blessing

When the editors at Jewish Life asked the venerable civil rights leader W. E. B. Du Bois to speak about the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, they had no idea that it would lead to a priestly blessing.

Ink and Blood

Arthur Szyk may well be the only great Jewish artist whose work countless people recognize simply because they have attended a Passover Seder. Less well known are the explicit connections between the Egyptian pharaoh and Hitler that Szyk had embedded in his original version of the haggadah he created in the 1930s.

A Book and a Sword in the Vilna Ghetto

If the destruction of Jewish culture and Jewish life were intertwined, then the reverse was also true: The rescue of books, manuscripts, Torahs, and so on was almost as much a form of resistance as the preservation of life itself.

Killer Backdrop

If Auschwitz can have a gift shop, why can’t the Warsaw Ghetto have a love story?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In