Weird Big Brother

The eighteenth-century heretical movement led by Jacob Frank still casts a strange spell. Frank was born in 1726 in the Polish (now Ukrainian) province of Podolia, where his father evidently had connections to Sabbateans, Jews who believed that even though Shabbtai Zevi had publicly converted to Islam in 1666 and died a decade later, he had still somehow been the messiah. Sabbateanism involved a variety of secret transgressive practices. Some of them upended sacred rituals, like transforming the Ninth of Av from a fast into a feast day; others were more shocking, including violations of sexual prohibitions.

Frank’s family moved not long after his birth to the Ottoman Empire, and he grew up in Sabbatean circles in Salonica and Smyrna, including the Dönmeh sect, whose members had followed Sabbatai by converting to a heterodox version of Islam. In 1755, Frank returned to Poland and connected with local Sabbatean groups. A scandalous incident in the small town of Lanckoronie, in which the Sabbateans, under Frank’s leadership, were accused of dancing around a naked woman, led to a rabbinic campaign against him and his followers, which culminated in two disputations. In the first, the Frankists argued that the Talmud was full of lies. The second disputation, which took place in Lwów (today Lviv) in 1759, included the dangerous accusation by the Frankists that rabbinic Jews used Christian blood. Shortly thereafter, Frank and his followers converted to Catholicism. Although the exact number of these converts is unknown, it appears to have been a few thousand, which would have made it the most spectacular instance of mass conversion in Eastern Europe.

Unsurprisingly, the Frankists immediately aroused suspicions within the Polish church that they were not sincere converts. An investigation resulted in allegations that Frank claimed to be the messiah (which was probably false). He was imprisoned for thirteen years in the monastery fortress in Częstochowa, the site of the worship of the “Black Madonna,” a medieval painting of a dark-faced Madonna and child. Under the influence of this cult, Frank came to identify his daughter, Eve, with both the Virgin Mary and with the Shekhina, the feminine divine presence. It was, in fact, Eve who became the true Frankist messiah.

After his release by Russian troops in 1772, Frank went to Brno in Moravia, where he contrived to live as a nobleman and was invited several times to the Habsburg court of Emperor Joseph II. Outstaying his welcome, he decamped for Offenbach in Germany, where his court became even more fantastical, with an armed guard and various strange rituals. He died in 1791 and was succeeded by his daughter, who died in 1816. After that, the movement, such as it was, vanished, although some families in Moravia and Poland continued to harbor memories of a Sabbatean past (the Jewish Supreme Court justice Louis D. Brandeis was descended from one such Sabbatean family, the Dembitzes).

In 2014, the Polish novelist Olga Tokarczuk published The Books of Jacob, a massive novel about Frank and his followers. Five years later, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, in large part for this novel. It has recently been translated into Hebrew, German, and French to great acclaim and success (it is a bestseller in Israel), and now it has been ably translated into English by Jennifer Croft. What are we to make of this Frankist War and Peace that sprawls over 900 pages? (Annoyingly, these pages are numbered in reverse order, apparently in a misconceived homage to Hebrew books, whose pages turn in the opposite direction.)

Tokarczuk is a talented and original writer, whose prose is lyrical in places. Here, for example, is how one of her characters imagines Poland from a distance: “crops, grain all along the horizon, light yellow, and interspersed in them the dark blue points of cornflowers; fresh milk and a just-cut loaf of bread that is lying on the table; a beekeeper in a halo of bees, extracting sheets sticky with honey.” She has also done a respectable amount of research, not only into the primary and secondary literature on Frankism but also into Kabbalah and Judaism generally—although she places two of Frank’s later disciples in the court of the Ba’al Shem Tov, which seems highly unlikely. Tokarczuk does a splendid job of evoking Jewish society in eighteenth-century Poland. Even when she constructs a seemingly unlikely erotic affair between Joseph II and Eve Frank, she is using a novelist’s license to build on rumors that in fact circulated about such a liaison.

There are occasional minor errors. For instance, she thinks mistakenly that the name Yente means a gossip (it only acquired that meaning on the Yiddish stage in the 1910s and 20s). And readers will be mystified by her repeated but untranslated use of the word “machna,” evidently the Yiddish makhne, meaning camp (as in group or party), which is how the Frankists referred to themselves (in some of the sources, they use a Polish word, kompania or company).

The novel unfolds in discrete episodic chapters with an enormous number of characters, who appear, then disappear, sometimes to only appear again hundreds of pages later. Some of these characters, such as the learned priest Benedykt Chmielowiski, the author of the encyclopedic New Athens, and Elżbieta Drużbacka, a Polish poet, have only the most tangential connection to the story of Jacob Frank. An enlightened doctor, Asher Rubin, appears in several places, evidently to give a sense of the incipient Jewish Enlightenment, but since Tokarczuk evidently hasn’t thought through the relationship of Frankism to the Enlightenment (a subject of much historical controversy), Rubin’s presence in this already overcrowded narrative feels superfluous. Tokarczuk also introduces a supernatural element in the person of Yentl, Jacob Frank’s grandmother, who is on her deathbed at the beginning of the novel but never actually dies. Instead, she becomes a somewhat distracting ghost who hovers over the whole story, possibly standing in for the omniscient author herself.

One way in which very long novels succeed is by depicting characters whom the reader is eager to follow through hundreds of pages, but in The Books of Jacob, even characters such as Nahman of Busk, whose Frankist chronicle Tokarczuk imagines in detail, remain one dimensional. At times, she uses such characters as expository props to explain Frankist theology, but even when she turns to their inner lives, they generally remain undeveloped ciphers.

This is, in fact, the problem with Jacob Frank in Tokarczuk’s novel. An early description of Frank in the novel—he appears after some two-hundred pages—suggests her inability to fully capture him:

Jacob Frank’s face is oblong, and he’s fairly light-skinned for a Turkish Jew; his skin is rough, especially his cheeks, which are covered in tiny pits that must be scars, like an attestation of some calamity, as if a flame had harmed his face at some point in the distant past. There is something unsettling about that face . . . and it also arouses an involuntary respect—Jacob’s gaze is completely impenetrable.

The historical Frank was, in fact, a bizarre, slippery, hard-to-define character. At times he played the holy fool, whereas at others, he could be dictatorial and cruel, as Gershom Scholem described him:

A truly corrupt and degenerate individual . . . a dictator who could snuff out the last inner lights and pervert whatever will to truth and goodness was still to be found in the maze-like ruins of the “believers” souls.

The contemporary historian Pawel Maciejko, whose definitive biography of Frank and his movement seems to have been one of Tokarczuk’s main sources (at times, her language tracks closely with his), takes a more measured approach than Scholem. He sees Frank as a genuine religious thinker who conceived of a kind of universalist religion that superseded Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Yet Maciejko also depicts Frank as one of the many charlatans of the second half of the eighteenth century, a purveyor of exotic magic and kabbalistic mysteries from the East. Such figures, including the famous Italian adventurer Giacomo Casanova, attracted a lot of attention in elite circles, which was perhaps one reason that Frank achieved entrée to the Habsburg court. But like many such charlatans, he was also a con man who swindled his followers to satisfy his lust for luxury.

A number of recent historians, such as Maciejko and Ada Rapoport-Albert (whose important book on women and the Sabbatean movement Tokarczuk seems not to have read), emphasize the originality of Frank’s theology. He devised a seemingly egalitarian worldview in which not only was his daughter the incarnation of the Shekhina and the Black Madonna, but his female acolytes were equal to his male disciples. He called himself “Big Brother” and held that the brothers and sisters in his company were destined to have sexual relations with heavenly entities he called the “divine brothers and sisters.” Jay Michaelson has argued that this was part of Frank’s religious materialism: the divine powers were to be brought down to earth. All of this was taught in a thoroughly antinomian context in which the fact that the messianic age had come meant that the Torah of Creation had now been replaced by the Torah of Emanation and everything that had been prohibited was now permitted. Although Tokarczuk alludes to much of this, the theology never comes into clear focus.

Given the lack of clarity in the historical sources, some of which were violently anti-Frankist, I had hoped that Tokarczuk’s novel might offer a compelling imaginative reconstruction of who Frank and his followers were. But, in this, she does not succeed. Her Frankists are like the disciples of Jim Jones, members of a cult who, instead of drinking the Kool-Aid, took the baptismal waters. Frankism was, undoubtedly, a cult of the personality, but in The Books of Jacob, Frank’s personality remains almost entirely opaque. We’re never sure from the novel why the Frankists embraced Frank as their leader.

As is often the case with cults, sexual transgressions played a role, and, for Tokarczuk, it is a major role. Her Frank is a sexual libertine who sleeps with and even impregnates many of his female followers. She describes the Sabbateans adopting a practice of sharing their wives or daughters with male houseguests and plausibly portrays Frankist women as reluctant partners in these practices, though no sources that I know of attest to this.

Some historians have doubted such stories, arguing that it was enemies of the Frankists, like Rabbi Jacob Emden, who deliberately exaggerated Frankist rituals and turned them into stories of wanton debauchery. What Tokarczuk misses is the highly ritualized way Frank deployed sex and combined sexual freedom with asceticism. As Rapoport-Albert writes:

The apparent licentiousness of the Frankist court should not be viewed as wanton anarchy. . . . On the contrary, the sexual contraventions practised there . . . were always performed at [Frank’s] own dictate, in carefully prescribed manners, and at particular times and places. . . . Not unlike the halakhah that he repudiated so savagely, he produced his own set of “prohibitions and permissions.” . . . It is quite possible that the ritualized violations of sexual prohibitions . . . were interspersed with periods of total separation between the sexes.

Tokarczuk is certainly within her rights as a novelist to portray Frankist sexuality as she does, but the historical truth may have been much more interesting.

In general, Tokarczuk does not fully capture how weird and inventive Frank and other eighteenth-century Sabbateans actually were. Not that she isn’t aware of it—she scatters some of the evidence throughout the book, but it is unlikely to register with anyone but the tiny minority of readers who are already conversant with the sources.

For example, at one point, more or less out of the blue, Tokarczuk puts in the mouth of Reb Mordke, an older Podolian Sabbatean, the following: “The world doesn’t come from a kind and caring God. God created all of this by accident, and then he was gone.” This would appear to be based on the anonymous manuscript And I Will Come Today to the Fountain, which was written by Jonathan Eibeschütz, one of the most bizarre and perplexing figures in earlymodern Jewish history, a leading rabbinic figure whose works are still studied in yeshivot and who was also a radical crypto-Sabbatean. Tokarczuk mentions this book once in passing and, from her note on sources, evidently read an article by Pawel Maciejko, which he expanded later into the introduction to a critical edition of this work. But Eibeschütz’s book is much stranger than this short quotation suggests. The book is filled with the wildest sexual fantasies projected onto God. It would be fair to say that Eibeschütz was writing a kind of kabbalistic pornography. Maciejko’s spellbinding introduction is one of the most astonishing revelations of the Sabbatean mentality and is much more shocking and provocative than anything in The Books of Jacob. (Eibeschütz was not a Frankist—And I Will Come Today to the Fountain was written before Frank was born—but his son Wolf later became closely associated with Frankists.)

Frank’s own tales, which were recorded by his disciples in the 1780s, make for equally bizarre reading, but Tokarczuk fails to exploit the full impact of this work, known as The Words of the Lord. Here is a story Frank told of entering a synagogue in Salonica as a young man, just before the reading of the Torah:

I shouted in a mighty voice, “let no one come up to the pulpit because I’ll knock him down on the spot.” In amazement, everyone began to shout, “how is it that you prohibit this?” So, shouting the same again, I grabbed the pulpit and cried out that I would murder anyone who dared to come up and, then having taken the Scroll of the Laws of Moses, I put it on the bare ground and, lowering my pants, sat on it with my bare behind, and all the Jews, being unable to do anything, had to leave.

What are we to make of this gross desecration of the Torah? First, it is almost certainly an invention of Frank’s feverish mind, projected back to his time in the Ottoman Empire. Second, it is intended to illustrate to his followers both his rejection of the law and his uncouth, ignorant, and violent nature, of which he was exceedingly proud. Third, it is a good illustration of Frank’s scatological sense of humor.

Here is another tall tale that was probably also intended to be funny:

In my youth, my member was so lively that when one time a youth wanted to climb a tree, I erected it for him to stand on and he climbed up on it. Also, it would still stand in the coldest water. And when I went among the maidens, I had to tie it up because, without that, it would stick out of my garment.

As with Eibeschütz in his anonymous manuscript, so Frank used his stories as a vehicle for pornographic fantasies. That such stories revel in the violation of Jewish law goes without saying, but they are much more a total breach of Jewish decorum and ethos, as well, arguably, as a liberation of the imagination. At a time when the nascent Hasidic movement was obsessed with controlling sexual “alien thoughts” during prayer, Frank was reveling in them.

Why did the Frankists convert to Catholicism? Tokarczuk seems to think that this was Frank’s plan all along. Oddly, she never mentions that the Dönmeh sect, with which Frank had extensive contacts, were crypto-Sabbateans who had followed Shabbtai Zevi into Islam. Although Frank converted to Islam before returning to Poland in 1759, the story of the mass conversion to Catholicism appears to be more complicated. Maciejko shows that the Frankists initially wanted to be allowed to live as Jews who rejected much of rabbinic law: they were anti-talmudists but regarded themselves as Jews nonetheless. There were church authorities, most notably Bishop Mikołaj Dembowski of the Kaminiec diocese in Podolia, who initially supported the Frankists, but there were also those who opposed them. When Dembowski died in 1757, the Frankists found themselves in an untenable position, as they no longer had any support for living as heterodox Jews and the rabbis were intent on driving them out of the Jewish community. Conversion was therefore as much a response to this impossible situation as it was the product of a Sabbatean theology. The blood libel that the Frankists leveled at Judaism in the Lwów disputation may have actually been suggested (or even compelled) by the Christian authorities. Later, of course, Frank came to embrace the conversion, but even then, he fashioned it in terms equally heretical to Judaism and Christianity.

Whatever its merits as historical fiction, Tokarczuk’s novel must also be seen as a bold and provocative intervention in contemporary Polish culture. In interviews, she has said that she is trying to reimagine Poland at a time when right-wing nationalists are trying to limit Polish patriotism to a narrow ethnic identity. At one point in the novel, she has one of her characters observe that “no real heresy could ever come about in Polish. By its nature, the Polish language is obedient to every orthodoxy.” It is exactly that propensity to orthodoxy in contemporary forms that she intends to disrupt. Another character states that “the Jews are probably the only people who can be of any use in this country.” Like the POLIN Museum in Warsaw, The Books of Jacob aims to put the Jews back into Polish history—and not just any Jews, but the most scandalously heretical ones at that!

The Poland that Tokarczuk imagines is multiethnic and multireligious with space for those who either have no religion or are inventing their own. Jacob Frank may have been a sexual adventurer, a brutal cult leader, or perhaps even a kind of religious genius, but, Tokarczuk argues, he belongs to Poland no less than the Black Madonna or John Paul II.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Secularism and Sabbateans

How did the Jews become modern? Three new books trace the roots of Jewish secularization.

A Tale of Two Exiles

What did a seditious Sicilian duchess and the heretical son of a chief rabbi have to do with the beginnings of French antisemitism?

The Secret Metaphysician

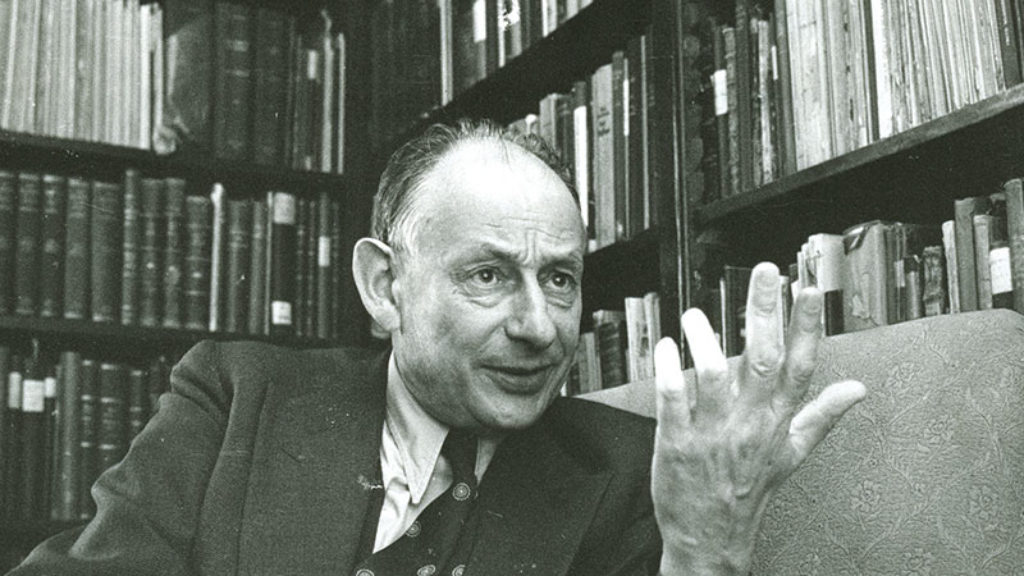

While a new crop of biographies about Gershom Scholem all, in one way or another, seek to account for the great man's fascination, they are themselves evidence of Scholem’s ongoing allure.

Says Who?

Peter Berger listened to me patiently, and then he said, “You can come to see me, but”—and here he spoke with heavy emphasis—“it sounds like you have read my books . . . and I haven’t thought of anything new.”

gershon hepner

FRANKLY I DON’T GIVE A DAMN

Some people treat all facts as pegs

on which broad theories may hang,

but often theories have legs,

and so some try, without a bang,

to make the facts explode,

in order to accommodate

their beauty, like a winding road

unobstructed by a gate.

Brandeis did this with success,

warning “Knowledge is essential

to judging,” implying this process

depends on knowledge’s potential,

which makes me wonder if he knew

that Denbitz, his new middle name,

that of his uncle, a good Jew,

was one that Sabbateans claim.

He gave his last name to a college

but the new one he adopted

must have been based on lack of knowledge,

that it by Frankists was co-opted.