Says Who?

In 1990, just back from studying in Jerusalem for a year, I talked my way into a miserable job in the Los Angeles office of a major Jewish organization. I was called an assistant director of something or other, but my actual duties, such as they were, seemed to consist in helping my boss raise funds to cover his salary and the overhead, and writing a superfluous newsletter, in which I struggled to find the nonexistent sweet spot between synagogue announcements and corporate press releases. We worked in a dingy office on Fairfax that might have been previously occupied by Philip Marlowe (I could have used his drawer flask). There was a modeling agency, or so it claimed, on the first floor, a kosher pizza parlor down the street, and a sweet old barber named Nathan Newman around the corner who had grown up in the famous town of Mezheritch and survived more than one camp.

One of the things about having a truly bad job is that you find yourself not just bored but needing to remind yourself of whom you are. I had picked up a little green paperback copy of Peter Berger’s The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion somewhere, and I read dense, nourishing bits of it on my lunch hour, puzzling over Germanic formulations such as “Man, as we know him empirically, cannot be conceived of apart from the continuous outpouring of himself into the world in which he finds himself. . . . Human being is externalizing in its essence and from the beginning.” (In the margins, I scribbled, “Read Hegel!”—probably still a good idea.) But Berger could also hit you with an epigrammatic little dart: “[R]eligion,” he wrote, “is the audacious attempt to conceive of the entire universe as being humanly significant.”

In The Sacred Canopy Berger argues that the modern state and economy require social spaces and institutions that are free, or mostly free, from the domination of religion and its symbols. In this connection, he liked to quote the 17th-century Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius, who said that if international law was to be effective between states with different established religions, it must be framed “as if God did not exist.” And as between states, eventually, so too within them; thus, modern workers had to leave their religion at the factory gates. Or, to quote the famous advice from the poet Yehudah Leib Gordon to his fellow 19th-century Jews: “Be a man in the streets and a Jew at home.” But—and this returns us to Berger’s Hegelian point—if you get used to leaving your religion at home, you end up thinking secular thoughts, which leads to the further decline of religion.

This process of secularization inevitably forces religions to enter the marketplace to compete for adherents, but the experience of different options on the consumer side necessarily relativizes the absolute claims of religion. Meanwhile, on the producer side, religious institutions must rationalize themselves along modern, corporate lines in order to effectively compete in the modern world.

These points were not all original to Berger. But he brought them together in a persuasive intellectual package that, unlike the accounts of some of his fellow postwar “secularization theorists,” fully recognized the depth of religion. In fact, in a move he owed to Max Weber, he argued that the seeds of this secularization lay not only in the modern reorganization of society but in religion itself—or at least the Bible’s original uncompromising rejection of Near Eastern polytheism and, closer to home, the Protestant disenchantment of medieval Christianity. Moreover, as he periodically made clear, while this was his value-free sociological analysis, Berger was himself a serious Protestant who still found what he called “signals of transcendence” in our doubly disenchanted world.

When I got to Harvard for graduate school, I called up Berger at his Boston University office. Eagerly, I told him that I had read his work closely and that I was planning to write a dissertation on the Jewish Enlightenment, which I wanted to discuss with him. “Well,” he said, “you do know that I am not Jewish . . .” I was a bit nonplussed. Here was this giant of social theory, who sometimes used Jewish examples to illustrate his points, and yet he seemed to be suggesting that the fact that he wasn’t Jewish disqualified him from discussing a topic in Jewish studies. I scrambled for an answer by delivering a presumptuous little lecture on how his theory of secularization applied to the Jewish case, but of course he knew this. After all, hadn’t he written at the very conclusion of The Sacred Canopy that “the fundamental option between resistance and accommodation must be faced by Judaism, particularly in America, in terms that are not too drastically different from those in which it is faced by the Christian churches”?

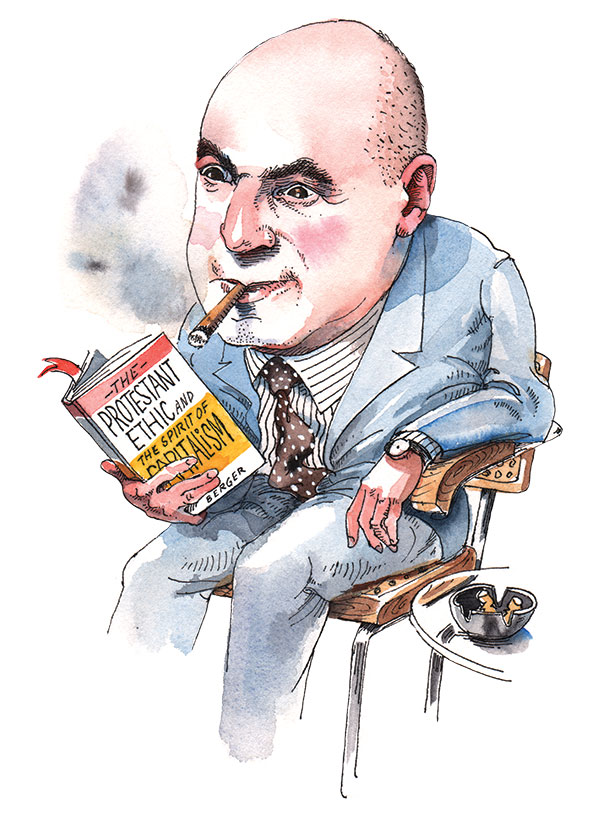

Berger listened patiently, and then he said, “You can come to see me, but”—and here he spoke with heavy emphasis—“it sounds like you have read my books . . . and I haven’t thought of anything new.” That remark did its work. I never forgot it, and I didn’t call Berger for another 20 years, though I did think that I saw him once on the Green Line at the Copley station, looking more or less as he had on the back cover of Facing Up to Modernity: bald with a brown cigarillo, like a bookie lost in thought.

As it happens, just a few years later Berger actually did think of something new. As he charmingly tells the story in his introduction to The Desecularization of the World: Resurgent Religion and World Politics, his reconsideration of his old theory crystallized when a massive volume called Fundamentalisms Observed landed on his desk:

The Fundamentalism Project was very generously funded by the MacArthur Foundation . . . The book was very big . . . the kind that could do serious injury. So I asked myself, why would the MacArthur Foundation shell out several million dollars to support an international study of religious fundamentalists? Two answers came to mind. The first was obvious and not very interesting. The MacArthur Foundation is a very progressive outfit; it understands fundamentalists to be anti-progressive; the Project, then, was a matter of knowing one’s enemies. But there was also a more interesting answer. “Fundamentalism” is considered a strange, hard-to-understand phenomenon; the purpose of the Project was to . . . make it more understandable. But to whom? Who finds this world strange? Well, the answer to that question was easy: people to whom the officials of the MacArthur Foundation normally talk, such as professors at elite American universities. And with this came the aha! experience. The . . . Project was based on an upside-down perception of the world, according to which “fundamentalism” (which, when all is said and done, usually refers to any sort of passionate religious movement) is a rare, hard-to-explain thing. But . . . [t]he difficult-to-understand phenomenon is not Iranian mullahs but American university professors—it might be worth a multi-million-dollar project to try to explain that!

Berger had often remarked that sociology asks the nervy little question “Says who?” and now he asked it of his colleagues and himself. Not only hadn’t the world secularized in the way that he had thought it would, but the religions that were resurgent weren’t the kind that had made peace with modernity. Instead, “movements with beliefs and practices dripping with reactionary supernaturalism (the kind utterly beyond the pale at self-respecting faculty parties) have widely succeeded.” Modernity, Berger went on to argue, does lead to pluralism, and pluralism does tend to relativize religious belief, but it hasn’t led to a thoroughly secular world, nor will it. As soon as one stepped out of the faculty lounge, Berger said, one saw that people moved much more easily from the enchanted groves of tradition to the iron cage of modern rationality and back again than Max Weber, or indeed he, had ever thought possible.

In 2012, I finally got back in touch with Berger. By then, I was editing this magazine, and I wanted him to write for me. His email back was not quite as discouraging as our phone call 20 years earlier, but it was not dissimilar: “I’m not looking for new places to publish (having, as you know, already contributed greatly to the deforestation of the planet)—also, I’m over-burdened with work—also (though this may not be relevant, since you describe the publication as ‘catholic, as it were, in its interests and approaches’), I’m not Jewish.”

Eventually, I prevailed upon him to review Michael Walzer’s latest book The Paradox of Liberation: Secular Revolutions and Religious Counterrevolutions (“Paradox or Pluralism?,” Summer 2015). It was obviously right up his alley, since Walzer’s paradox was that religion had returned with a vengeance to countries, like Israel, that had been founded by radical secularists. By this time, I also understood his sensitivity about not being Jewish, because I now knew that he was—or rather that he had been born to Jewish parents in Vienna, in 1929. A recent book called The New Sociology of Knowledge: The Life and Work of Peter L. Berger by Michaela Pfadenhauer had crossed my desk, and, in her introduction, she briefly sketched Berger’s early years, based upon a German memoir he had published in 2008. From Pfadenhauer, I learned that Berger and his parents had converted just before fleeing the Nazis in 1938, eventually ending up in British Mandate Palestine. She also wrote that Berger had been hesitant to publish the memoir, even in German, because some of his “Jewish friends might feel snubbed by . . . a decision against a Jewish identity on his part.”

Peter and I bantered on the phone and through email while we worked on the Walzer review. I didn’t ask him how his life experience related to his sociological theory of religion, though I couldn’t help but wonder. Twice, I came close. The first time was when he included a joke about speaking Yiddish in Israel in his piece. The second was when he excitedly told me that he had been invited to address the German Protestant Assembly, and I almost told him the one about the Jewish convert who is invited to give the Sunday sermon and begins, “My fellow goyim . . .” It would have been presumptuous (again), but he probably would have laughed. He enjoyed telling Jewish jokes more than most Lutherans I have known.

Several months later, I visited him at his apartment in Brookline. It had been a hard year. His beloved wife and intellectual collaborator Brigitte Berger had passed away, and he himself was wheelchair ridden and not well. But he did want to talk. We continued our conversations about religion, doubt, and moderation and about books on which we agreed and disagreed (including his), and he told me the story of his early life.

His parents were both assimilated Viennese Jews. In 1938, they had gone with a nine-year-old Peter and some other family members to an Anglican cleric who was converting Jews in order to help them flee Austria for a small fee. The conversion was perfunctory. In his memoir Im Morgenlicht der Erinnerung: Eine Kindheit in turbulenter Zeit (In the Dawn of Memory: A Childhood in a Turbulent Time), he wrote that his uncle leaned over “and said with a cynical grin, ‘So now you are baptized!’ I remember how terribly embarrassed I was and I felt somehow humiliated.” From there, they went to family in Monfalcone, near Trieste, but they soon realized that they wouldn’t be able to stay in Mussolini’s Italy. A sympathetic official at the English consulate finally relented when his mother burst into tears, and offered to give them papers to either Kenya or Palestine.

They chose Palestine, because, his mother said, it seemed “less alien,” but when they arrived in Haifa they remained Christians, sending Peter—Ya’akov on the Hebrew-speaking street—to a Swiss missionary school. When he was old enough for high school, his schoolteacher took him and two other “Hebrew Christians” to the famous Beit Sefer ha-Reali, but they were rejected by the headmaster as being potentially subversive (“ein zersetzendes Element”), which, Peter said, was the second time he had heard himself being rejected on such grounds by a representative of the majority. Instead, he went to St. Luke’s Anglican School, where most of his teachers were former Jews. At St. Luke’s, he was given free rein of the theological library left by a certain Pastor Berg who had returned to Germany. In these years he became a fervent, if, as he later recognized, very idiosyncratic, Lutheran “without ever having met one.” After the war, the Bergers left for America as soon as they could. At one point in our conversation, he remarked with some wonder, but no regret, that had things gone slightly differently he might have become an Israeli Jew rather than an American Protestant. His English-language memoir, Adventures of an Accidental Sociologist: How to Explain the World Without Becoming a Bore, picks up with his arrival in America and never mentions any of this, though it does have a Jewish joke on the first page.

I thought about my conversation with Peter often in the months that followed, and I sometimes wondered whether I could get him to write about his years in Haifa and their bearing on his later thought, but I never quite got up the nerve. He passed away last June at the age of 88, having done as much to illuminate the place of religion in the modern world as anyone in the last century. Although none of the obituaries I read seemed aware of Berger’s Jewish background, I wasn’t the only one who had noticed.

This spring, the Committee for the Study of Religion at the CUNY Graduate Center held a memorial conference for him. Its organizer, the distinguished sociologist Samuel Heilman, had studied with Berger at the New School for Social Research in the late 1960s, but he hadn’t known his teacher’s history until Professor Alan Brill told him about it after Berger’s death. In Heilman’s perceptive talk, he described the central theme of Berger’s work as the way in which fate becomes choice in the modern world and persuasively interpreted his German memoir in that light. In Brill’s equally fascinating lecture, he told us that Rabbi Alexander Schindler, the long-time president of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, had once consulted Berger about whether the Reform movement should seek converts. The great sociologist replied that it might as well, since all denominations must compete in a pluralist world. Needless to say, Schindler did not ask the nervy follow-up question: Says who?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Quality of Rachmones

Howard Jacobson's Shylock Is My Name is dead serious and very funny, high criticism and low comedy.

Equine Ambles into a Watering Hole: An Interview with Jessica Cohen

An interview with Jessica Cohen—winner of the 2017 Man-Booker International prize for her translation of David Grossman’s Horse Walks Into a Bar—on translating Hebrew literature and jokes.

Jerusalem Reconstructed

The Mendelsohns' converted flour mill on the outskirts of Rehavia became a cultural salon, with concerts and poetry readings.

Memories of Morocco

In the 1940s Moroccan Jews were still sacrificing a bull on the Sultan’s doorstep. There was a deep cultural symbiosis of Jews and Muslims in North Africa.

dennis.karpf

Gratitude is given for a well intentioned writer and deep thinker of the virtuous role of religion in America and as foundation for Western civilization; but only with exercise of personal and collective conscience and self-restraint. Nonetheless deep sadness is felt for another whole family and successive generations lost to HaShem, and Judaism, which began it all and ever still guides all the West to betterment, by the most successful ideology of the 20th Century—anti-Semitism. Why was escape but not return a success for Peter Berger?

Justin Jaron Lewis

Well said, Dennis Karpf. And why did he identify himself so unequivocally as "not Jewish"? Surely he knew as well as anyone that believing in another religion is not necessarily enough to make a person "not Jewish"! Those who knew his background didn't ask him enough questions!