North Africa during World War II

For many people, mention of wartime North Africa conjure ups visions of Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, and Claude Rains in Casablanca. Yet as grim as this classic film made things look, it only dimly reflected the actual experience of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya during World War II. Under the rule of the Vichy French, the Italian fascists, and the Nazis, the people of the entire region suffered terribly from mass imprisonment in forced labor and internment camps, governmental thievery, the imposition of racist and antisemitic laws, and the need to cope with a huge influx of European refugees. The worst things were, of course, the work of the Nazis, who deported some of their victims (Muslims as well as Jews) to European death camps. They did the same to North African Jewish émigrés living in France and also imprisoned North African and West African soldiers serving under the French flag in POW internment camps in France.

Many North African Jews and Muslims have told the story of what happened to them during this bleak period, as have others who shared their lot, including European refugees, former volunteers for Spain’s International Brigades or France’s Foreign Legion, interned and forced laborers, and French “colonial soldiers” from North and West Africa. No one has pieced these narratives together, however, to obtain a composite picture of wartime North Africa in all its diversity.

It isn’t easy to do so. To locate the testimonies that make up our forthcoming book from which these selections are taken, Wartime North Africa: A Documentary History, 1934–1950 (Stanford University Press), we had to comb through archives, libraries, and private collections across North Africa and West Africa, the Middle East, Europe, and the Americas. We searched through books of all different sorts, from memoirs to diaries, collections of poetry, and more, and had to translate most of the selections from French, Arabic, North African Judeo-Arabic, Spanish, Hebrew, Moroccan Darija, Tamazight (Berber), Italian, and Yiddish. Together, they show how what took place on the southern periphery of the Nazi empire mirrored what went on deeper into its interior.

We do not know whether Eugène Boretz, the author of our first selection, is a name or a pseudonym, or even whether he was Jewish and Tunisian. Published in Algiers in 1944, after its liberation, his French-language chronicle about the two-year Italian and German occupation of Tunis reads like a diary, replete with details that provide a vivid picture of the deprivations that accompanied everyday life. But he also describes the special vulnerability of Jewish women and girls to sexual violence at the hands of the occupiers.

Ernest Sello, the author of our second selection, joined the French Foreign Legion early in the war. Following the Nazi conquest of northern France and the establishment of the Vichy government, he was deported to the forced labor camp of Bou Arfa in Morocco. In September 1941, he attempted to escape. After his capture, he was sent to the subcamp of Aïn al-Ouraq, where he was sentenced to spend eight days in the “tombeau,” which entailed lying still and unable to move in a trench shaped like a grave. Sello’s time in the tombeau coincided with a winter freeze, during which he suffered severe frostbite on both feet. The overseers of the camp hoped to deport him to Germany, but thanks to the intervention of the Bou Arfa doctor, he was instead sent to a hospital in Oujda, where both his feet were amputated.

When his case came before the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society and Jewish Colonization Association, organizations that collaborated in North Africa during the Allied occupation, one philanthropist ruefully called Sello “the person who most embodies contemporary history.” The organizations arranged for Sello to have artificial limbs fitted to his body, but unfortunately, he had no way to pay for them. Sello’s wartime testimony was shared with the American Friends Service Committee.

__________________________

Excerpts from Wartime Africa: a Documentary History, 1934–1950, appearing this summer, are reprinted with the permission of Stanford University Press.

A Wry Account of Occupation in Tunis, (1942–1943)

By Eugène Boretz

Countless groups of soldiers roam the streets. They inundate all the restaurants, all the stores, purchasing with rapacity and carelessly removing wads of large bills from their pockets to pay. They spend abundantly and have easy money. Everything interests them, particularly wine. They have bottles under their arms, in their hands, they fill trucks and cars with them. The Bank of France’s money waltzes with joy!

But it is above all the garages that become the centers of feverish activity. They are all busy with the invaders who take over all the private cars that have been parked for years due to lack of gasoline. [It is the] first attack on private property even before any decree initiates the right to requisition.

The Germans are busy, the cars are repaired in haste and swarms of vehicles crisscross the avenues like race cars, mingling with the first foreign military trucks.

Tunis, deprived of automobiles for two years, rediscovers the intense traffic of before the war, and its appearance is changed. A few days later the first street signs with German inscriptions appear at the most splendid intersections . . . completing the modification of the city’s appearance.

They are everywhere. The most sumptuous hotels, Tunisia-Palace and the Majestic, are requisitioned, first in part, and then the civilians are [totally] driven out. In the entrance hall to the Tunisia Palace, signs in three languages inform interested parties that “Jews are unwanted.” The new Belvedere neighborhood has become a colony of Germans. First the Jewish villas are requisitioned, but soon the others are as well. In fact, it is rare for a building not to be either totally or partially occupied. The Germans camp in the superb Belvedere Park, the pride of Tunis. Entry there is forbidden.

It should be noted that, on the intervention of the Italian authorities, Italian Jews were not taken as hostages. On this subject, there arose a conflict between the Italian and German commands, and, in a rare twist, the Italians prevailed after Rome had been alerted. Italy intended to protect its Jews as best it could. It proved this on many occasions, despite its submission to its powerful and irritable ally.

Let us note here that the fate of the Jewish laborers consigned to the surveillance of the Italians was infinitely more kind. Humane working conditions, lack of bullying. In their conversations with the Jewish officials, the Italians like to declare that they were participating in political racism, but they vehemently protested when we pointed out that this policy could lead to cruelty: you are not dead, Machiavelli!

We easily appreciate that the spirit emerging from these official acts could only have the effect of unleashing the army rabble’s basest instincts and opening the gates to violence and arbitrariness. Without doubt, we will never be able to know the extent of all the excesses with which the occupation troops defiled themselves in the darkness of the Tunisian nights. But those who lived in Tunis during these months of shame know of isolated, controlled, undeniable events. They know that, revolver in hand, Germans entered Jewish homes and took their linens, clothes, and valuables, and threw the men out into the street in order to be one-on-one with the women.

Such was the influence of the occupation on the appearance of Tunis, on its charm. Caring about complete accuracy, let us stick to the facts. Suppose that you want to spend an evening with friends somewhere in or around Tunis. Where will you go?

Will you go to Belvedere Park? Don’t bother thinking about it. The Axis troops are camping there and entry is forbidden.

Will you opt for the movies? Alas! They are all closed, except the Deutsches Soldaten-Kino. But this is not for you.

The theater? Give it up. Besides a few shows for the German army, the theater is only used for propaganda shows organized by the infamous COSI or collaborating companies, with official representatives of the occupation army, national revolutionaries, high-ranking collaborationists, etc. A bit uncomfortable.

So, you think you will go to one of these intimate restaurants where they usually serve copious and succulent, if not always lawful, meals. And you are already on your way. You open the door and, in the overcrowded room, you see officers from the occupation army at almost all the tables. But, weary and famished, you resign yourself and your friends to wait for a free table. You have accepted the idea of . . . “protecting” neighbors.

But while you wait, a hand places itself familiarly on your shoulder and a friend leads you all into the street under some pretext. “You are free to dine at this restaurant,” says the friendly voice, “but at the very least, know the risks of such an undertaking. A German officer could very well ask your names and addresses and invite you all to spend the next day at the Kommandantur. There, they will ask for proof that you are Aryan and, as he who is suspected to be Jewish is also suspected to have false papers, they will ask you to submit to an exam of your head, from the front, side, and three-quarters angle, according to phrenology’s most modern methods.” You laugh heartily, but the friend continues: “This is exactly what happened yesterday to a young woman from high society, and pure Aryan, to boot. Believe me, it is better to follow the wise counsel of Colonel Heym, vice president of the Municipality, who, in a recent notice, asked his people to remain in their homes as much as possible. So, return to your homes, and the sooner the better, since you are with a woman. Ever since the ‘tourists’ have been here, a woman who looks young, even if she is accompanied, risks a lot being in the street after sundown.”

So much for fun times!

Surviving the “Tombeau” 1943

By Ernest Sello

I, the undersigned, Ernest SELLO, engagé volontaire for the duration of the war and appointed to the Foreign Legion, was placed in Bou-Arfa labor camp after the armistice.

After escaping from the camp at the end of September 1941, I tried to cross the border into Spanish Morocco, where I was arrested and taken back to French Morocco.

At the end of the month of November, I was sent to the Ain-el-ourak penal camp. There, I was punished with eight days in the “tombeau,” [a grave shaped trench] having only my tattered clothing and one light blanket to cover myself with. The only food I received was one round loaf of bread every twenty-four hours. This was the end of the month of December, and it was very cold. At the end of my punishment, I was taken out of the “tombeau” with two frozen feet and sent to the Bou-Arfa infirmary.

During my punishment, I asked for help and care several times, but had no success whatsoever.

When I found myself in the Bou-Arfa infirmary, Captain Avelin and Commander Janin made efforts to have me repatriated to Germany. Only the intervention of the Bou-Arfa doctor prevented my departure. In January 1942, I was sent to the hospital in Oujda where I had both of my feet amputated.

For the past twenty months, I have been in different hospitals without having ever received help from the [French Ministry of] Industrial Production and Labor, which didn’t even judge it necessary to clarify my situation with regards to my becoming unfit for service and my pension.

Suggested Reading

Sephardi Lives: From Ottoman Salonica to Rosario, Argentina

Singing women spark indignation in Salonica, a change of seasons in Argentina requires rabbinic expertise, and Jews in the Ottoman army get fat and happy.

Orphan Soldiers

When WW II seemed all but lost, Britain knew that it had to take impossible risks, including turning Jewish refugees into crack commandos.

Victim Enough? The Jews of North Africa During the Holocaust

As the Tunisian Jewish novelist Albert Memmi wrote, “I am not enough of a victim; that is why my conscience is tortured.” Must the Jews of North Africa, as contributor Lia Brozgal puts it, write “a history that competes with a more catastrophic one, or be written out of history?”

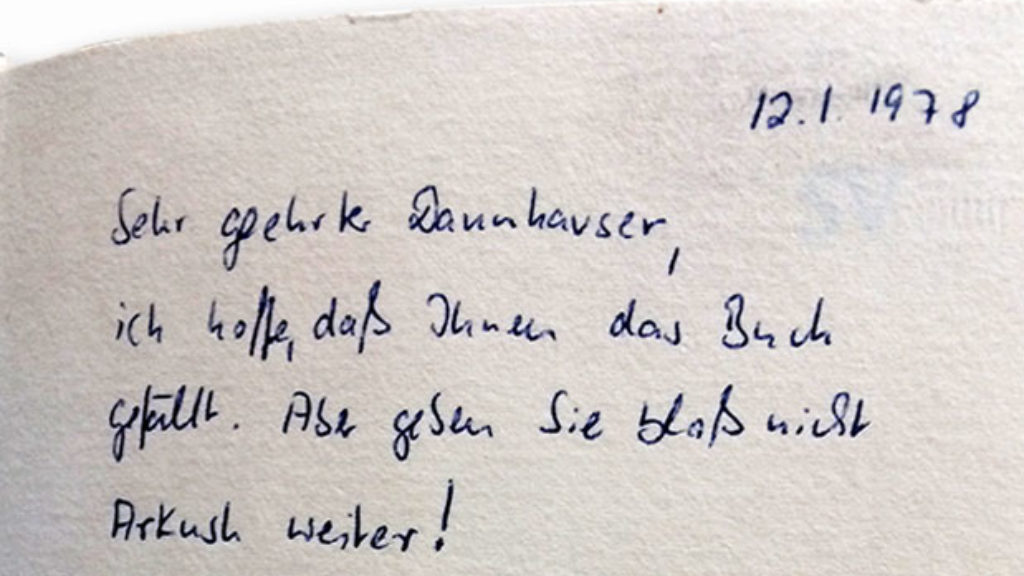

Scholem!: From Berlin to Jerusalem to My House

“Arkush, Arkush. What does that mean?” That was the third question one of the greatest Jewish scholars of the 20th century asked me.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In