Scholem!: From Berlin to Jerusalem to My House

“Arkush, Arkush. What does that mean?” That was the third question one of the greatest Jewish scholars of the 20th century asked me. But before I explain what led him to pose it, I have to set the stage a little better.

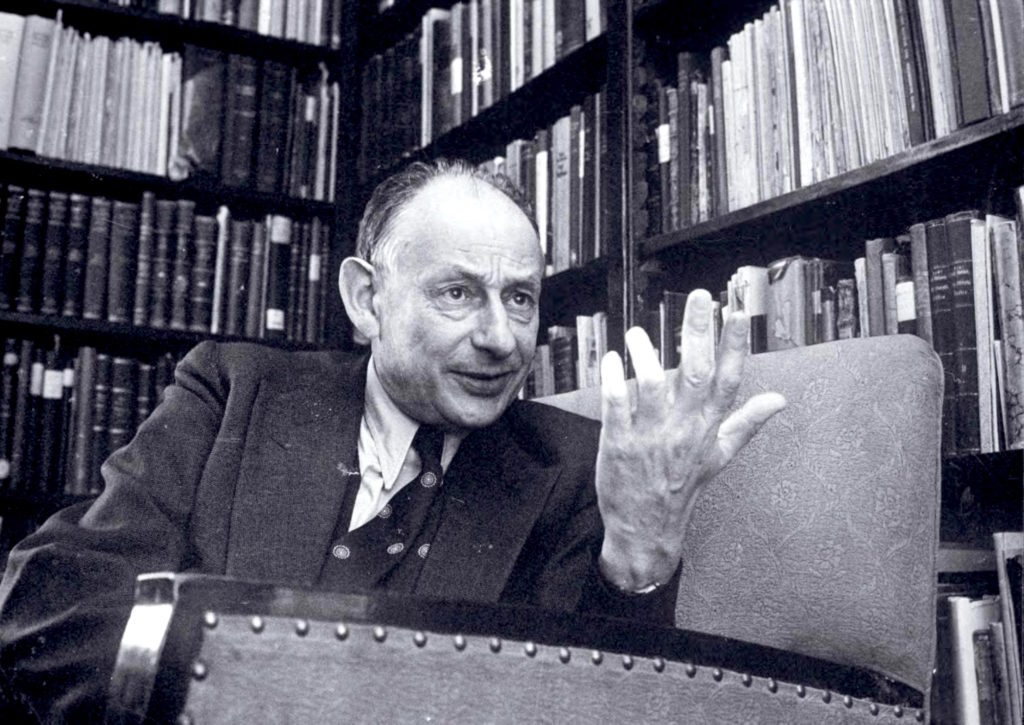

Late in the winter of 1975, about a year and a half after the death of the political theorist Leo Strauss, an evening event was held in his memory at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute. There may have been more than three speakers, but the only ones that I remember were Shlomo Pines of the Hebrew University, Strauss’s collaborator in the now-standard English edition of the Guide of the Perplexed; Gershom Scholem, the renowned scholar of Jewish mysticism and a longtime friend of Strauss; and Strauss’s student Werner Dannhauser, a professor of political science at Cornell University (where he had been my teacher during the 1960s).

After the lectures, Scholem hosted a gathering at his apartment in Rechavia, to which I was—sort of—invited, solely by virtue of my connection with Dannhauser. But I had to run to get to it, together with Laurie Mylroie, then an undergraduate on leave from Cornell who was enjoying her first experience in the Middle East as a babysitter for the recently widowed Dannhauser’s children during his sabbatical (off-duty that night, she was to play a controversial role in the buildup to the Iraq War, a quarter of a century later). The two of us raced on foot across Jerusalem to Scholem’s famous apartment on Abravanel Street, where Dannhauser’s friend, the noted Hebrew-English translator Dalya Bilu—unlike us, she had gotten a ride— waited in the street to guide us to the right door.

Scholem himself let us in and after closing the door stretched out his very long arm to me and declared rather loudly: “Scholem!” I don’t think I had ever been greeted that way before, but I got the message, extended my own arm, and uttered both my first and last names.

“What was that? What’s your name?” he asked, in English.

“Allan Arkush,” I repeated, perhaps a bit louder.

“Well. Mr. Arkush,” Scholem announced, “there is only one thing wrong with you. You mumble!” But that didn’t lead him to lose interest in me. “Arkush, Arkush,” he mused and then asked the question about my name with which this essay began.

I find it very hard to believe now, but I had the temerity to say, “You tell me.” He was, after all, known to be a great savant, well versed in many subjects besides his main area of expertise.

Scholem looked down and askance at me, as we made our way down a corridor to his living room. “No. No. No. Surely you have some idea what your own last name means!”

“I’ve been told,” I said, “that it means paper in Polish.”

Just then, we reached the rest of the crowd of a couple of dozen people. Drowning out their conversation (to my ears, at least), he shouted across the room to the woman I subsequently learned was his Polish-born wife: “Fania! Does Arkush mean paper in Polish?”

With two words, she confirmed that it did: “A ream.” That let me off the hook and freed Scholem to torment someone else.

More than 40 years later, I don’t remember much of what took place after this slightly traumatic encounter. All I can clearly recall is a point later in the evening when the crowd had dwindled to a handful of people. We were all sitting around Scholem who was pontificating about many things but interrupted himself at one point to announce that “Now I will turn to my favorite subject—me.”

Scholem is admittedly a fascinating subject, as the recent spate of biographies of the man, appearing more than 30 years after his death, clearly attests. They’re all worth reading, but if you want to know his life story, the best place to begin may be his autobiography, From Berlin to Jerusalem: Memories of My Youth. He wrote it in German, but I first read it in the English translation of Harry Zohn (who was my teacher in graduate school, at Brandeis) when it came out in 1980. It is from this book that I learned what might have been the source of Scholem’s intense interest in surnames. He relates how in 1812, when a Prussian edict required all Jews to assume permanent family names,

[a]ccording to family legend, my great-great-grandfather was summoned to the town hall and asked what his name was. He did not understand the question and answered “Scholem,” whereupon the official entered it as his family name. When he was asked his first name, he impatiently repeated “Scholem.” This is how we received our family name. In other documents, I found my great-great-grandfather mentioned as Scholem Elias – that is, Scholem, son of Elias. The truth of the matter is that he died between 1809 and 1811; thereupon his widow Zipporah appeared at the town hall and declared that she was adopting her late husband’s name as her own and her children’s family name.

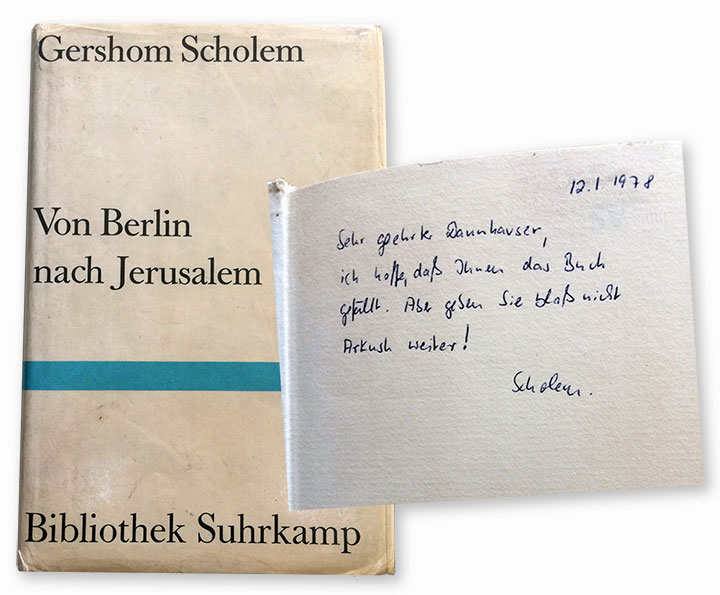

This information appeared near the beginning of a fascinating book that I didn’t see in the original German until around 1983, when Dannhauser showed me the copy that Scholem had sent to him in Ithaca five years earlier. The most startling thing about it was the dedication that the author himself had inscribed on the flyleaf: “I hope that this book pleases you. But just don’t pass it on to Arkush!”

This admonition couldn’t possibly have been the result of our awkward conversation in the hallway of his apartment in Jerusalem in 1975. It probably had something to do with the fact that at the time he wrote the dedication I was busy translating his Origins of the Kabbalah into English (a job that Dannhauser, who had translated many of Scholem’s essays, had turned down and for which he had recommended me). But exactly what it was that Scholem was trying to convey I don’t know and probably don’t want to know.

For decades, the gift volume occupied a prominent place on what Dannhauser called his “honor shelf.” It was the section of his oft-moved library that included all the books that he himself had authored, in whole or in part, and all of the books that his many friends and students had dedicated to him. Von Berlin nach Jerusalem even made the final cut—it was among the relative handful of books that he took with him to his last residence, in a small unit at the Frederick Mennonite Community, not far from Ursinus College in Pennsylvania, where his son-in-law Jonathan Marks teaches political science.

Werner Dannhauser was an honorable man, and I never dreamed of asking him to do what Scholem specifically asked him not to do. But when he passed away in 2014, I asked Jonathan if he would let me have the only book in which one of the world’s leading Jewish scholars had once inscribed my name. And now it’s mine. Given the nature of the dedication, however, I wouldn’t think of putting it on my honor shelf—even if I had one.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Saving the World

There are at least two problems with the widely repeated narrative about Rosenzweig's sudden commitment to Judaism: It’s historically false and philosophically pernicious.

The Book of Radiance

Daniel Matt’s massive new English edition of the Zohar is not only a great translation, it is also one of the great commentaries on the classic work of Jewish mysticism. Insofar as it is possible, Matt has brought the unfathomable, mysterious, and poetic depths of this “book of radiance” to the English reader.

Pro-Creation

Economist Bryan Caplan thinks parents “overcharge” themselves when it comes to investing in their children. Glückel of Hameln knew better.

Doron Rabinovici and the Crisis of European Jewish Identity

To live in Vienna as a Jew is also to be reminded that those who perpetrated the Shoah were defeated yet, unlike the victims, were able to resume their lives afterwards.

marcus

Oddly disquieting