Chaim Grade: Portrait of the Artist as a Bareheaded Rosh Yeshiva

I first met Chaim Grade (pronounced Grahdeh) in the spring of 1975, when he visited our home in the Bronx. My parents were ardent Yiddishists who followed Grade’s serialized novels in the Yiddish press, but they didn’t know him personally. Grade came to our home because we were hosting a friend of his, Yudl Mark, the editor of the Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language, who lived in Israel. Grade had come over to ask Mark some questions about Yiddish grammar and spelling and to enjoy the company of a fellow Litvak (Lithuanian Jew) away from his apartment on Gale Place where he lived with his wife, Inna, who was not interested in such questions and did not like her husband’s friends.

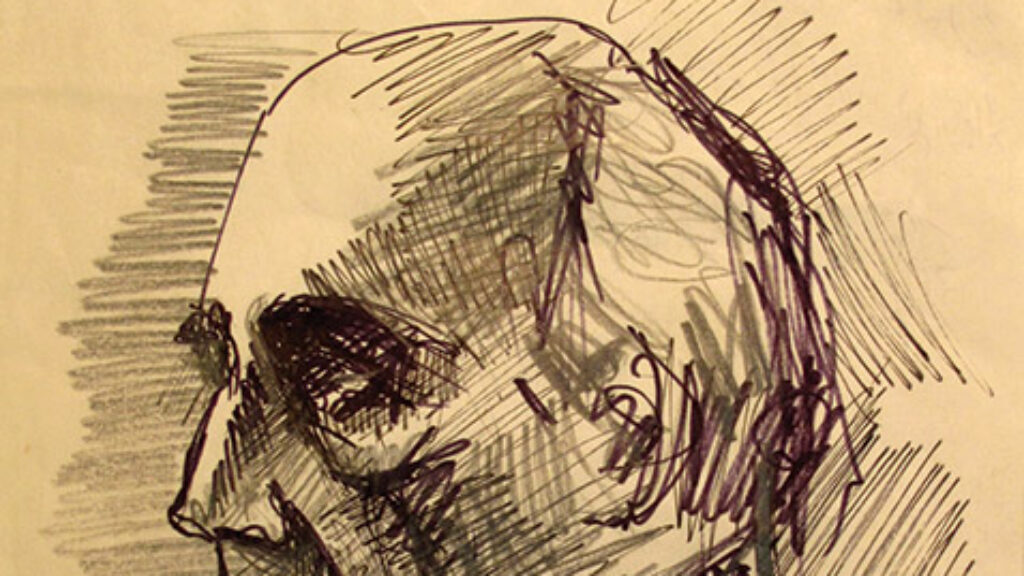

The guest who came to visit our guest was a short, round man with a large, bald head with a little white hair around the edges. His manner was gruff, and he had a voice that sounded like he was arguing, even when its volume was low and its tone soft. His eyes flashed, and his right hand was very active—his index finger pointing upward, his palm moving abruptly sideways, his fist tapping his interlocutor on the shoulder.

I was a sophomore at Yeshiva University, and I immediately recognized the similarities in style and comportment between Grade and my Talmud rebbe, Rav Aaron Kreiser, who had studied in the most famous of Lithuanian yeshivas, Mir. But Grade was bareheaded and a famous Yiddish writer. Upon hearing that I was a student at YU, he asked me what Gemara we were studying and what daf we were on. As soon as I told him, he started reciting the page by heart and gave me a summary of Rashi and Tosafot. I had never met a bareheaded rosh yeshiva before. Then Grade lost all interest in me and in the Talmud and spent the afternoon with his friend and landsman, talking about Yiddish literature and the finer points of Yiddish grammar and spelling. He was, I would later realize, the Yiddish writer of breaks and divisions. He crossed many boundaries in life, but none of them was resolved or overcome. His biography was a series of tensions and dichotomies.

Chaim Grade was born in Vilna, the Jerusalem of Lithuania, in 1910 and died in what for him was exile, in New York City, in 1982. His father was a maskil, a moderately enlightened Jew who studied the Bible with Moses Mendelssohn’s commentary, and his mother was a pious woman who recited tekhines and read the Tsena-Urena (Yiddish prayers and homilies on the Chumash for women). Grade spent eight years of his youth, from age fourteen to twenty-two, immersed in the world of Lithuanian yeshivas and rabbis, more than any other modern Jewish writer. He spent several of those years in the extreme pietist environment of the mussar yeshivas of the Novaredok school, only to totally break afterward with religious observance and the Orthodox milieu. He then spent ten years, from age twenty-five to thirty-five, in the company of modern Yiddish poets and leftist Jewish intellectuals, first in Vilna, among the writers of the “Young Vilna” group, and later in the Soviet Union. (In Moscow, he lived in the home of Yiddish novelist David Bergelson.) Grade always remained true to his secularism but abandoned his leftism after leaving the USSR in 1945.

From late 1941 to mid-1943, Grade was a homeless refugee in Soviet Russia and Central Asia. He had fled from the Germans, while his mother and first wife stayed behind in Vilna, where they perished. His guilt and anguish at their loss became a driving force in his literary creativity.

Grade started a new life in the United States in 1948, at age thirty-eight. His first wife had been a rabbi’s daughter who went to nursing school. His second wife, Inna, whom he met in Moscow, was a Soviet-born student of world literature who didn’t care about Judaism and didn’t speak Yiddish.

Grade was a self-taught man of broad cultural erudition, all of which he acquired on his own. He was fascinated with Dostoevsky (one of his main literary influences), Balzac, and Spinoza but had little interest in American literature. He spoke English with a heavy accent (“I vant you should noe”), and he refused to lecture in English, in part out of embarrassment and in part as an expression of his commitment to Yiddish. At home, he and his wife spoke Russian.

Another border that he crossed was literary. Grade began as a poet who was crowned by critics as the “Yiddish Bialik.” His first book of verse, Yo (Yes), was one of the few such collections to enjoy a second edition, and by 1947 he had published five volumes (in Vilna, Moscow, Paris, Buenos Aires, and New York). But he achieved much broader acclaim later on as a novelist, a genre that he adopted only after immigrating to the United States. In 1978, when Isaac Bashevis Singer was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, many Yiddish readers (Elie Wiesel and Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik among them) thought that Grade was more deserving.

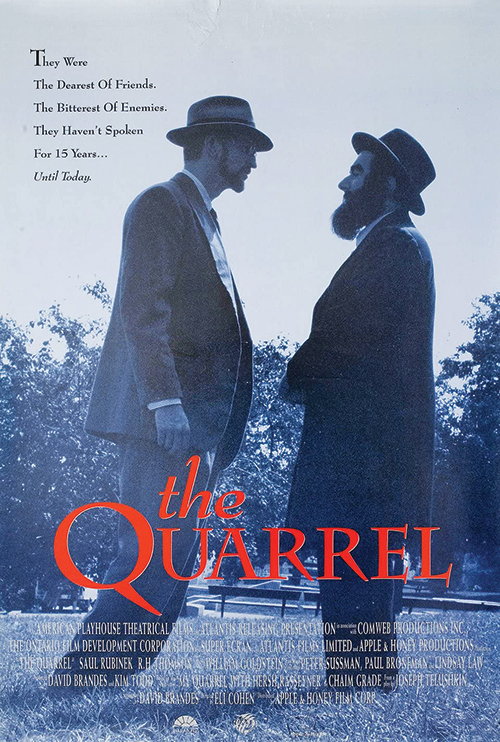

Many of Grade’s unresolved contradictions are on display in his very first experiment in prose, “My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner,” which has now been published in a new translation with an instructive and eloquent introduction, both by Ruth R. Wisse. (The new edition also includes the Yiddish text, “Mayn krig mit Hersh Raseyner.”)

“My Quarrel” was originally published in 1951 in the Labor Zionist magazine Der yidisher kemfer (The Jewish Militant) and appeared in an English translation by Milton Himmelfarb in Commentary in 1953. The story consists of a series of impassioned debates between Grade’s barely fictional alter ego Chaim Vilner and his friend from his yeshiva days, Hersh Rasseyner. (In Lithuanian yeshivas, students were called by the name of the city or town from which they came.)

They meet in Poland in 1937 before the war, then in Soviet-occupied Vilna in 1939, and finally in Paris in 1948. Their third meeting, after both have lost their families and communities in the Holocaust, is by far the longest and most intense. Rasseyner was an inmate of the Vilna Ghetto and of a concentration camp in Latvia. Now he is a rosh yeshiva for other survivors. Theirs is a debate about faith and doubt, Torah and European civilization, enlightenment and assimilation. In the aftermath of the Khurbn, the Destruction (as the Holocaust is referred to in Yiddish), their opposing worldviews have hardened and sharpened, but their feelings for each other have become a complex mix of affection and rage. At the outset, Rasseyner asks Grade with whimsical contempt: “Maybe you still believe in this cruel world?” and Grade retorts with bewilderment, “And you . . . do you still believe in God’s particular providence?”—that is hashgocha protis, the divine providence through which God guides particular human lives.

Hersh Rasseyner is based on Rav Gershon Liebman, who was a mussarist rosh yeshiva in France after the war. There are conflicting reports on whether the historical Chaim and Hersh met briefly or at length and whether their encounter took place in Paris or on New York’s Lower East Side. But in either case, Wisse is right to remind us that both voices speaking in the story are Grade’s, and his ability to compellingly express the worldview of a Lithuanian rosh yeshiva after the Holocaust is a literary tour de force. No one had ever done that before in Jewish literature.

The story quickly became a classic in English. It was published in Irving Howe and Eliezer Greenberg’s pioneering 1954 anthology A Treasury of Yiddish Stories and from there made its way into other anthologies. Critics and rabbis viewed the story as a paradigm of Holocaust literature that addressed the religious, philosophic, and artistic issues raised by the destruction of European Jewry. It was adapted to the stage and made into an ambitious film.

But, surprisingly, among Yiddish readers the story had little immediate resonance. No Yiddish critics reacted to “My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner,” and Grade’s biographical entry in the Lexicon of Modern Yiddish Literature mentioned the English translation but not the original. The story was overshadowed by Grade’s first novel, Der Mames Shabosim (My Mother’s Sabbath Days), which began appearing in installments in the Yiddish press during the same year, 1951. It was the elegiac novel rather than the philosophical dialogue that captivated the imagination of Yiddish readers and critics.

My Mother’s Sabbath Days was largely a vivid and affectionate portrait of the poor Jews from Grade’s childhood courtyard in prewar Vilna, with the character of his wise and pious mother, who peddled apples on the street, in the foreground. It was also the story of a young man moving away from his mother’s world, in search of his own path in life. The novel had no yeshivas and only a brief cameo appearance by a rabbi.

In a sense “My Quarrel” is an outlier in Grade’s prose, and My Mother’s Sabbath Days was the foundation of everything that followed. “My Quarrel” is the only work by Grade that takes place mainly after the Holocaust, and the characters react to the catastrophe directly. All of his subsequent major novels, The Well, The Yeshiva, The Agunah, The Silent Minyan, and so on, take place in prewar Vilna and nearby towns in Lithuania. There isn’t even a chapter or a scene set in postwar New York, where Grade lived for thirty-four years.

In his major works of prose, Grade set out to reconstruct the world of prewar Jewish Vilna: street by street, one house of prayer after another, character type by character type—rabbis, businessmen and street peddlers, pious congregants and underworld criminals. His plots unfold against the backdrop of an ethnographically rich picture of prewar life, depicting the home furnishings, foods, clothing worn by men and women of different social classes, medical remedies, and local lore.

Grade attempted to perform the impossible: to undo in literature what had occurred in history. His literary mission was to revive the dead of Jewish Vilna, or, more precisely, to write as if they were still alive. The novels that effect this techiyas ha-meisim (revival of the dead) neverrefer to or hint at the subsequent destruction of Vilna’s Jews. There are no flash-forwards to the ghetto, no retrospectives by a survivor, no ominous shadows. The narrator always seems to be speaking as if it is August 1939, and he doesn’t know what will happen to his characters during the next few years. The Holocaust was the driving force behind Grade’s prose, but it was not an overt theme. Except for “My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner.”

But in a different sense “My Quarrel” was just as foundational for his later work as My Mother’s Sabbath Days. It was Grade’s first attempt to explore the inner spiritual and personal struggles of a rabbi. Rabbis had figured previously in Yiddish literature, but they were usually secondary characters who were lampooned (as in the work of Mendele Mokher Seforim), portrayed as wise father figures (Sholem Aleichem), or used to represent abstract values and ideas (I. L. Peretz, S. An-sky). Grade portrayed rabbis as human beings. He populated his works with a whole class of men with beards and caftans (and some women in wigs), each with a differing temperament, personal fate, professional career, and religious outlook. While a few of these rabbis were cynical political operatives or cowardly conformists, most were men of conviction, learning, and insight who had confronted temptation and suffering.

Yiddish critics were ambivalent. In reviewing Grade’s second book of prose, Der Shulhoyf (The Synagogue Courtyard), the great critic and poet Jacob Glatstein praised the book’s portraits of rabbis as “Rembrandtian” but noted that their discussions of halakhic issues were dry and inartful. Yiddish literature shouldn’t be written for translation, he wrote (in a likely barb at Isaac Bashevis Singer), but it also shouldn’t be untranslatable. He advised Grade to leave the synagogue courtyard for more accessible settings. Little could Glatstein have imagined that it was precisely Grade’s exploration of the inner world of rabbis and religious Jews that would attract generations of readers to his works—in translation.

The yeshiva in the town of Novaredok (Russian: Novogrudok, today in Belarus), founded by Rabbi Yosef Yozel Hurvitz in 1896, paid less attention to study of the Talmud than to the struggle to improve one’s religious and moral character. The goal was to defeat the sinful urges that control human behavior: lust, greed, pride, laziness, anger, and so forth. Ritual observance was considered necessary, but not particularly difficult or challenging, compared with the quest for religious and moral self-improvement. In the words of Grade’s longest and most ambitious novel The Yeshiva, “It is easier to observe dozens of laws and customs than to deny oneself a single forbidden desire.”

In Novaredok, the struggle to improve one’s character was pursued through a series of structured activities: Students studied classic ethical and pietist texts while in a state of extreme emotional excitement (lernen muser mit hispayles), so that the words penetrated their inner being. They attended impassioned motivational sermons on self-transformation (muser-shmuesn) by the rosh yeshiva, and engaged in introspection while in seclusion (hisboydedes) in a tiny dark room called a Muser-shtibl. They met with their peers daily to share psychological insights while moving across the study hall in alternating pairs (the birzhe [bourse], a kind of spiritual speed dating), and they belonged to groups that held weekly meetings to examine each member’s progress (va’ad). Finally, each student engaged in operations or missions (pe’ules) that were tailor-made to improve a specific character trait in which he was somehow deficient.

Because of these activities, in Novaredok the relations between students were intimate and intense. They knew virtually everything about each other and constantly judged each other. Only total, brutal honesty toward oneself and others, unrelenting criticism and self-criticism, would lead toward their goal—moral perfection.

In “My Quarrel,” when Chaim Vilner meets Hersh Rasseyner on the street in Bialystok, Poland, in 1937—their first encounter since Vilner left the yeshiva several years earlier—Hersh immediately launches into a tirade against his former friend’s character and career as a writer.

Do you think that by running away from the yeshiva you have saved yourself? . . . Chaim Vilner, you will remain a cripple. You will be deformed for the rest of your life. You write godless verses and they pinch you on the cheek for it like a heder child. . . . Is there really one of you so self-confident that he doesn’t go around begging for words of approval? Is any one of you prepared to publish his book anonymously?

And Vilner, as a former Novaredoker, responds in kind:

Hersh, now you listen to me. No one knows better than I how torn you are. . . . You hang on to your fringes like a drowning man to a rope—but it doesn’t help you swim against the current. . . . When you go off to your solitary garret it’s because you would rather have nothing at all than take the crumb that the world throws you. Your modesty is really pride.

The two sustain this relentless style of verbal combat over the course of all their exchanges, though the focus shifts after the war to questions of theology and Jewish identity.

Nvaredok, which grew into a network of seventy yeshivas with three thousand students by the 1930s, was the most extreme wing of non-Hasidic Lithuanian Orthodoxy. According to Hurvitz and his disciples, those who did not focus their lives on the study and cultivation of mussar were slaves to their desires and impulses. Even most Orthodox Jews were, they held, infected with sinfulness—theirs was a superficial, bourgeois piety. Hurvitz and his disciples drew a sharp line between the yeshiva, which strove for perfection, and the world, which was immersed in sin. There was nothing in between. Compromise and gradualism in the quest for self-transformation were futile. If you wanted to make your kitchen kosher, you needed to throw away all the old dishes and buy new ones. Replacing one dish at a time would accomplish nothing.

The greatest sin of all in the Novaredok lexicon was to fall under the spell of social conventions and expectations. The truly pious seeker (mevakesh) had to be ready to withstand public ridicule. Novaredokers, including Hersh Rasseyner, wore tattered clothes in public, with long tzitzit that reached down to their ankles. The paradigmatic act of Novaredok self-correction (pe’ule) was to walk into a pharmacy and ask the druggist for nails. The goal was to be indifferent to the laughter and derision of others in one’s quest for self-perfection.

These ideas and practices were all developed before the First World War. Hersh Rasseyner is a Novaredok mussarist who adheres to them with even greater fervor after the horrors of the Second World War. He rails against modern Jews:

You prophesied: “Man will be a god.” So naturally he became a devil. . . . Instead of looking for solace in the Master of the World and in the Community of Israel, you’re looking for the glass splinters of your shattered dreams. . . . Still, not all of your secularists wanted to cast off the yoke of the Torah altogether. Some grumbled that Judaism kept getting heavier all the time: the commentary of the Gemara on the Mishnah, Alfasi on the Gemara, one commentary on another, and commentaries on the commentaries. Lighten the load a little, they said, so that we can carry the rest more easily. But the more they lightened the burden, the heavier the remainder seemed to them. . . . What the father rejected in part, the son rejected in its entirety. And the son was right! If there’s so little, he doesn’t need it at all. A half-truth is no truth.

There are three layers of language in “My Quarrel.” First, there is Yiddish, the common language of Eastern European Jews, with its idioms and expressions. In the story, most of which takes place in Paris, in the metro and the Place de l’Hôtel-de-Ville (City Hall Plaza), Yiddish sets Chaim and Hersh apart from their environment. They are East European Jews, with a distinct culture and fate. Passersby cannot understand them. The second layer of language is specifically rabbinic, with its citations and allusions to religious texts, practices, and concepts. This language sets Chaim and Hersh apart from most other East European Jews, who would not have been able to follow their learned volleys. The third layer is the mussar language of Novaredok. Novaredok speech binds Chaim and Hersh intimately together; it is almost a private code. But it also sets them against each other, since Chaim rejects its underlying ideas. He speaks like a Novaredoker with Hersh to reject and undermine Novaredok.

It is the achievement of Wisse’s translation that it restores the Jewish specificity and flavor to Grade’s text, in translating the Yiddish and rabbinic speech. Himmelfarb’s original rendition of “My Quarrel” elided many of the internal Jewish cultural allusions and rabbinic textual references. For example, when Chaim meets Reb Hersh in Soviet-occupied Vilna in 1939 and feels obligated to explain that he does not support the Communists, Chaim quips: “Hersh, because you consider me treyf doesn’t mean that they consider me kosher.” Himmelfarb simply skips the passage, which is standard Yiddish speech. Wisse reinstates it.

When it comes to rabbinic speech, the new translation goes even further. It gives Hebrew phrases and verses in their original Hebrew, transcribed according to their Ashkenazi pronunciation and followed by their translation: “You have traded in our menuhas ha-nefesh, our tranquility of spirit, for what?”; “All of your scribbling is an abomination, muktseh makhmes miyes—forbidden because disgusting”; “‘K’nesher yo’ir kinoy,’ the Torah carries us as an eagle carries its young.” Even the reader who knows no Hebrew will sense the particular style of rabbinic speech. Of course, this is not to say that a reader ignorant of rabbinic life will not still miss some nuances in “My Quarrel,” but that is inevitable. Thus, when Reb Hersh asks Chaim Vilner whether he or any of his artistic peers would be modest enough “to publish his book anonymously,” many will not know what he and Chaim take for granted: that rabbinic scholars sometimes did just that.

Where the new translation comes up short is in translating the characters’ Novaredok speech. Chaim Vilner asks Reb Hersh: “How can you expect to change them [human beings]? With a va’ad, a circle, a birzhe, or by shaking while studying Tomer Devorah?” But Wisse’s translation follows its predecessor by rendering the sentence: “How can you expect to change them [human beings] with your Musar methods of rooting out the passions and studying remedial texts?” Although one might need a glossary to do better, this leaves something to be desired.

For Grade, the Novaredok movement embodied religious fanaticism and deep-set hostility toward human nature. But it also represented something larger: the destructiveness of aggressive, totalizing ideologies that strove for nothing less than perfection. In a telling phrase, a character in The Yeshiva called the Novaredokers “pious Bolsheviks.” (Grade, who had once been sympathetic to Communism, understood the analogy from both sides.)

“My Quarrel” stands out from Grade’s other works, in that he gave full expression not only to Hersh Rasseyner’s voice but also to his own voice as a modern Jew. He was unrelenting in affirming his right to disbelieve and in calling Orthodoxy to task:

Shall I see the greatness of God in the thought that only He, not flesh and blood, could cause such destruction? . . . I don’t consider it a special virtue not to have doubts. . . . The heroism of secular thinkers lies in their ability to risk and live with doubt.

We make it harder for ourselves by taking on a double responsibility—to Jewish tradition and to secular culture. . . . We try to bring them together in harmony where they don’t have to surrender their rights or their character. . . . It’s your fault that we moved too far away from Jewish tradition! You bolted every door and gateway. . . . Even today, if you could, you would expel people for the smallest transgression. . . . Even at this point, doesn’t your voice carry the sound of the shofar of excommunication?

While Grade completely rejected Novaredok mussar, its perspective had an enduring impact on his writing. Almost all of his characters, even the simple craftsmen and shopkeepers, think like Novaredokers, at least to a certain extent. They judge and analyze their own actions, they criticize the motives and actions of their friends and neighbors, they quarrel, reconcile, and quarrel again, and they brood over their suffering.

In Grade’s novels, life is defined by intense conflicts that are unavoidable, irresolvable, and ultimately of tragic consequences for those involved. Only rare individuals—such as Grade’s mother, Vella, and his rabbinic mentor after leaving the Novaredok yeshiva, Rabbi Avrohom Yeshaya Karelitz (known as the Chazon Ish)—are able to accept life as it is, in its beauty and tragedy. They feel the suffering of others and serve as a force for healing in their communities. Karelitz left Vilna for the Land of Israel in 1933, where he became the leading luminary of Lithuanian ultra-Orthodoxy. Grade’s final break with tradition took place shortly after his departure.

Wisse’s new translation of “My Quarrel” includes a chapter that was entirely omitted from the 1953 English version. In it, Grade introduces a third character, a student of Hersh Rasseyner’s named Yehoshua, who is stunned to find his teacher talking with a bareheaded Jew on the street. Upon learning that Chaim had once studied in the Novaredok yeshiva in Bialystok, Yehoshua’s attitude toward the stranger moves from incredulity to contempt. His every sentence is an insult, culminating in the accusation that the secular Chaim Vilner would never have had the courage of Reb Hersh to rescue a Sefer Torah from destruction or a student from death. He asks Grade point blank: Did you rescue your family? Chaim explodes. After the student departs, he lashes out at Hersh: “Is this what you teach?! Hatred and scorn for the whole world?” In this restored chapter, Grade seems to be warning readers that the new postwar generation of zealots would be much worse than their teachers. They would be mere epigones and caricatures.

Years after I met Grade at my parents’ home, he came to Harvard as a visiting scholar while I was a graduate student there, and we became close. From our conversations, I can say that he held a rather bleak view of postwar American Jewish Orthodoxy, and indeed of postwar Jewish life more generally. In Vilna and in Eastern Europe, Jewish life had integrity and its own poetic beauty. He saw the newer generations of Jews raised in the United States and Israel as shallow imitations of their forebears. The Israeli disciples of his mentor, Karelitz, the Chazon Ish, made him into an idol and accentuated his fanaticism. Similarly, American Zionists were manipulative politicians compared with the idealistic Zionists he knew in Vilna.

For Grade, history was divided into two: the prewar and the postwar. The former had depth, beauty, idealism, and integrity. The latter was cheap, superficial, and cynical. There was his prewar life (including his prewar wife) in Vilna, and there was his postwar life (including his postwar wife) in America. Grade had no children. The divide was unbridgeable, except in the imagination, in literature.

Grade’s personal literary challenge was to rekindle and retain his memories of Vilna and its rabbis and convert them into art. To do so, he spent hours upon hours talking with landslayt. They became his closest friends and the inspirations for his characters. But more than anything else, he relied on books and old photographs (including photo albums) to kindle and rekindle his memories.

Grade had an unusual relationship with his enormous library. It occupied all of his study, the room where he wrote his books. Down the middle of the room, there were rows of tall bookshelves, like the stacks in a university library. What surprised me most was the diversity of his collection. Only half the books were in Hebrew or Yiddish, and there were dozens of art albums. Every day he spent about half an hour reshelving his library, moving a bunch of books from one part of the room to the other. This was his main daily physical exercise. But beyond that, he said that it kept him in direct, living contact with his books. He’d reread a bit of this and a bit of that to refresh his memory. It was as if he was visiting with old friends. During those moments, he was back in Vilna.

One of Grade’s greatest regrets was that he had not chosen to settle in Israel in 1948. He had many close friends in Israel, including the country’s third president, Zalman Shazar. I am sure that he would have been much more at home there than he ever was in America. He once told me that he didn’t make the move and didn’t visit Israel until the late 1950s because he didn’t want to confront his rebbe, the Chazon Ish, face to face.

I would have had to visit him in Bnei Brak, and I know that seeing me as a secular person would have caused him great pain. I didn’t want to do that. And if I had visited him, he would have asked me to do teshuvah. I loved him so much, that perhaps I would have done teshuvah, and stayed with him in Bnei Brak. But I didn’t want to become that person.

This tragic contradiction between love and rejection is evident, too, in the final paragraph of “My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner.” After a full day of arguing, Chaim Vilner concludes:

Reb Hersh, it’s already very late, let’s take leave of each other. Our paths are different, both in spirit and in plain day to day. The storm that uprooted us is scattering the remnant to all the corners of the earth. Who knows when we shall ever meet again? May we both have the merit of meeting again in the future and seeing where we stand. And may I be as Jewish then as I am today. Reb Hersh, let us embrace.

Suggested Reading

A Book and a Sword in the Vilna Ghetto

If the destruction of Jewish culture and Jewish life were intertwined, then the reverse was also true: The rescue of books, manuscripts, Torahs, and so on was almost as much a form of resistance as the preservation of life itself.

On Chaim Grade’s Agunah

Chaim Grade’s Yiddish novel The Agunah is not so much a story about one woman’s plight as much as a whole city’s eruption over her story—the rabbis, the butchers, the mohels, the barbers, the housewives.

Translating and Remembering Chaim Grade

A memoir of faith, literature, and chickens.

Accounting for the Soul

Mussar Yoga makes for a surprising deli combo platter of the spirit, even in our easy-going mix-and-match America.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In