I Am My Own Lady Messiah

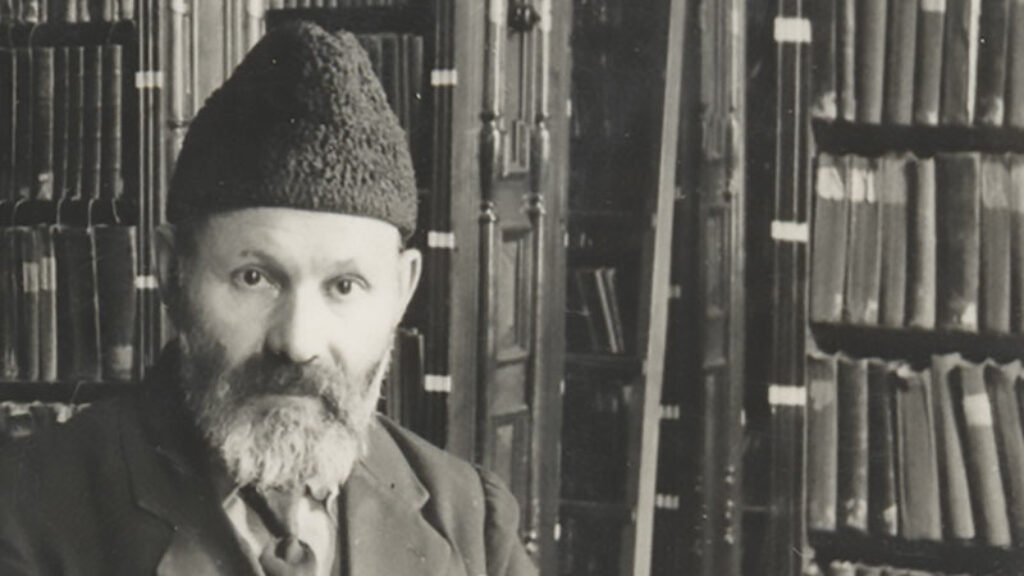

Miriam Karpilove (1888–1956) was a prolific author of novels, short stories, sketches, and feuilletons in Yiddish. She is best known for her serialized novels, five of which were published as books. Two of her books have appeared in English: Yudis, which I translated and published as Judith (Farlag Press), is an epistolary novel that follows the tumultuous relationship between a small-town Jewish girl uprooted due to antisemitic violence and the dashing revolutionary who routinely disappoints her. Tagebukh fun an elender meydl, oder der kamf gegn fraye libe, which I translated and published as Diary of a Lonely Girl, or the Battle Against Free Love (Syracuse University Press), is a wry first-person account of the disappointments, frustrations, and absurdities of a Jewish single woman’s love life among the radical immigrant Jews of New York at the turn of the twentieth century.

Karpilove was born near Minsk in today’s Belarus, immigrated to America in 1905, and debuted as a writer the following year at the age of eighteen. An active Labor Zionist, in 1926 Karpilove sailed to Palestine, hoping to settle there permanently. Describing her busy plans to leave for Palestine in the letter below, she wrote of the “too many things to do to prepare to release myself from golus [diaspora]. I am my own moshiekhste [lady Messiah] and as you know there is no white horse for me.” Here, Karpilove plays with narratives of exile and redemption defiantly and ironically, placing herself at the center of a story of her own making while also deflating it and its redemptive potential. She returned to the United States three years later having failed to make ends meet, but she brought back vivid stories of the widening stream of Jewish immigrants who were then settling in Mandatory Palestine.

The following letter, translated from a copy held in the YIVO Archives (RG 701, Records of the I. L. Peretz Yiddish Writers’ Union (1903–1973,), Series III (Correspondence) Box 9, Folder 176) tells Chaim Liberman, the Yiddish essayist and literary critic who served as the secretary of the I. L. Peretz Writers’ Union, about her plans for life in Palestine.

The next selection is a translated excerpt of the first chapter of Karpilove’s A Novel about Israel: My Three Years in Israel. The autobiographical novel’s handwritten manuscript remains in Karpilove’s archive at YIVO (Box 2), and chronicles the beginnings of the two years Karpilove spent in Israel, from 1926 until 1928. Chapters from this novel will appear in translation in A Provincial Newspaper and Other Stories (Syracuse University Press, forthcoming).

New York

July 18, 1926

Dear Secretary of the I. L. Peretz Writers’ Union— Chaim Liberman,

As soon as I received your letter I wanted to come and see you, but the new ticket system that the Board of Transportation is implementing, and so forth, took over and stopped the subway. So I’ll have to do as you say and send you what you want through the mail and receive what I need. It would be better to see you in person to explain certain reasons why and how I was, for a time, not in good standing as I ought to have been.

I will see you again someday and tell you everything, and let’s hope that we will meet as good friends. And you will all wish me a good trip to the land of our ancestors and future generations: Yes, dearest of all secretaries, I am going to the Land of Israel. I will be leaving in about a month, on the first of September, 1926. (You still have time to throw me a going away party with a banquet, or whatever else you like, to give my departure the celebration necessary in order to commemorate the significance of our Yiddish literary and cultural world in America…)

Aside from my passport and a trunk, there’s a lot that I still require… among those things is a job that would connect me to the press here in America that I have so honorably served for more than twenty years. (I’ve earned a jubilee celebration, right?)

But the things I lack won’t keep me from my journey. I am going. It’s decided. On the first of September, on the ship “Canada,” which will sail for a whole month to Palestine. The journey will certainly give me plenty of material to write about.

I will take with me a high opinion of our Writers’ Union: It always helped me not to forget to remember that I must understand that writing is an art, and not a job… and left me free to enjoy my freedom so I could depend on being independent.

And so, dear Chaim Liberman, Secretary of the I. L. Peretz Writers’ Union, don’t take it as an insult that I have not yet come to call on you. My weak head is dizzy with all of the things that I have to do for myself in order to leave from golus. I am my own moshiyekh’te [lady messiah] and, as you know, I have no white horse and, as you also know, the subway is on strike, to boot. Therefore, please accept my apologies for my distance, my tardiness, in following the aforementioned rules and regulations. Better still, maybe you can help me get my affairs in order. Maybe we can see each other again sometime, who knows? Maybe we’ll meet someday in the Land of Israel.

With the warmest, most collegial greetings to the new Board of Directors and the Executive Committee, I remain,

Miriam Karpilove

850 E 161 St

The Bronx, New York NY

Tel: Dayton, 6880, Ap 1B

“The Palestinian Ellis Island,” An excerpt from A Novel about Israel: My Three Years in Israel. Chapter One

As soon as we reached the shore, Arab porters fell on us like locusts. They tore our baggage from our arms and shouted at the other porters who tried to grab it from them. Moshe shouted over them. He told them to bring our baggage where we were going and not to confuse it with others’ belongings, and we continued on to the Palestinian “Ellis Island.”

Our way forward was difficult because of the sharp heat of the thick dust and the path paved with pointy stones. Uncle Shmuel could hardly keep up with the others. Old age hobbled his tired legs.

“He’s too old, isn’t he?” Izzy asked his mother, glancing over at his grandfather.

“He’s tired,” said his mother, who tried to help her father walk but he waved her away with his hand. He didn’t need any help, he wasn’t a cripple. He could walk fine on his own.

He and Moyshe went over to the side of the government building where a hand reached out through a window, like at a bank, to take passports from the new arrivals.

The government official wanted to hear an explanation for why the words “Born in Russia” were on the passport. “How old are you?”

Moyshe pointed to the passport. “It’s all written right there.”

Once we had finished with the governmental hand, we went to Zionist Organization’s office, where we had to pay a head tax: three pounds (five dollars) for each of us, including Izzy, the child, for a total of thirty five dollars. Plus an additional sum for our eight trunks and for the two visas that were delayed in coming from America.

Moyshe complained to the Zionist Organization for taking so much money, but they said they weren’t taking it for themselves but for the British government, for the Mandatory power that makes you pay more and more.

Shmuel was angry at my brother for paying so much money (for everyone’s head tax and the trunks). But my brother smiled good-naturedly, “Don’t worry uncle. It costs money because it’s worth money.”

Moyshe smiled broadly and called us all over to the medical department to get our smallpox vaccines. Entry into the country was strictly forbidden without the vaccine.

A guard stood by the open door to the medical department. He was a tall young man in shorts. Shmuel asked him a question: How long will that thing have to take? Was it possible to exempt him? He wanted to travel to Jerusalem as quickly as possible…

“Zeydenyu,” said the guard, “find a chair and take a seat until they call you. You came from America, right?”

“Yes, from America.”

“Over there they’re always in a hurry, but here Zeyde we take our time. Shwaye shwaye.”

We waited to hear the word “Next!” The old doctor and the not-so-young nurses grabbed an arm. They cleaned a small area of the arm, cut a small incision, gave a squirt, and it was done. Most people bit their lips but didn’t make a noise. They accepted the pain of the stab like it was something they deserved.

But not the girl who we nicknamed “the goat” on the ship because she leapt from third class to second and from second to first, where she even had the privilege of dancing with the captain. She made a fuss: Who asked them to stab her? If someone is healthy, why should they make her sick? This is the “pleasure” you get when you arrive in “The Orient,” which they advertise in such beautiful colors. It’s bad enough that it’s so hot and dusty and muddy, they also force unnecessary pain on you. “Some country,” she said in English, “Gee!” She looked through the window longingly toward the Canada, the old ship where she’d had such a lovely time.

Moyshe couldn’t stand to hear the girl criticizing Eretz Yisrael and said to her, “Miss, if you don’t like ‘The Orient’ then go back to your America. Your ship is still here.”

She didn’t like how Moyshe spoke to her. She retorted, “Fresh!” and turned her back to him.

Our uncle spoke to the girl. “Whether you need it or not, they’ll grab you and stab you. One law for everyone!” It’s a pity about the pain from the needle’s jab. As for him, he’d experienced much greater pain in his life. What bothered him was the waste of time. The doctor didn’t care about anyone’s time. He said that everyone had to return in three days. Anyone who didn’t would be severely punished. So, unwillingly, the old man had to put off his travel to Jerusalem. He’d have to go with us to Tel Aviv.

We had to make one more stop. We had to show a group of British government officers all of our documents so they could see that our coming here to Eretz Yisrael was kosher and we’d followed all the legal requirements they set out for us.

These government officials sat at a long table in the middle of a large room. We had to stand. Stand and wait in line until someone looked over our papers and gave them to another official, who gave them to a third official, and so forth.

More than anything, they noticed the stamp on our papers with the word “settler.” They were surprised that American citizens with money had come to settle in Palestine: Is it so bad in America, or so good in Eretz Yisrael, that the Jews would want to settle here? Especially during the present crisis? One of the officials asked my brother why he wanted to settle in Palestine, isn’t it good to be an American citizen?

“Oh, very good!” Jacob said. “But I think Palestine has more for us.”

“Remarkable…” he shrugged his shoulders and asked me what compelled me to settle in Palestine. I looked him straight in his squinty eyes and replied, “historical connections, you know…”

“So, so…”

They didn’t like us. I could tell. But we couldn’t ask them why… we had to just ignore their cold, dry demeanor toward us immigrants. I doubt if we’ll be able to accomplish much in Eretz Yisrael under the Mandate that they use to squeeze money out of us. We can only accomplish things that are in their interest. On the way to Eretz Yisrael we heard our fill about their decency, but now all we could do was console ourselves with the hope that it won’t always be this way. Someday we’ll come to an agreement. We will prevail.

Suggested Reading

Dress British, Think Yiddish

Stanley Kubrick was a New York Jew, fascinated with photography, jazz, and chess. He took evening classes at City College and studied at Columbia with Lionel Trilling.

The Great Family Circle

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, “the father of modern Hebrew,” famously raised his own son to be the first child in almost 2,000 years to speak only Hebrew. When Itamar Ben-Avi grew up, he was fascinated by . . . Esperanto. Esther Schor’s new book on L. L. Zamenhof, his would-be universal language, and those who still speak it inspired Stuart Schoffman to revisit the oddly parallel careers of Ben-Yehuda and Zamenhof.

Golden Books

Three decades ago, Allan Nadler went to Vilna to reclaim books that the Nazis had plundered from YIVO, or so he thought. Dan Rabinowitz’s Lost Library solves the mystery—and raises important questions.

A Book and a Sword in the Vilna Ghetto

If the destruction of Jewish culture and Jewish life were intertwined, then the reverse was also true: The rescue of books, manuscripts, Torahs, and so on was almost as much a form of resistance as the preservation of life itself.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In