The Tikkun in Sutzkever’s Work

The Yiddish literary elite’s response to the announcement, in 1978, that Isaac Bashevis Singer was that year’s Nobel Laureate for Literature was a quintessentially Yiddish one: kvetching drowned out celebration. Singer was viewed by a great many old-school Yiddishists as a sellout who published his books in English translation before the originals in Yiddish appeared, if they did at all. Many Yiddish readers, particularly Holocaust survivors, found Singer’s depictions of Jewish criminals, demons, dybbuks, perverts, pimps, and prostitutes to be a desecration of the sacred memory of the Yiddish civilization of their murdered parents, children, and siblings. And the reaction in Singer’s dwindling community of fellow Yiddish writers was an especially pointed case of life imitating art: Cynthia Ozick’s satirical novella Envy; or, Yiddish in America, published a full decade earlier, depicted the bitter resentments of an obscure, untranslated Yiddish writer toward his world-famous Singer-like colleague. The real-life bitterness was especially acute since it was understood that this would likely be the first and last Nobel Prize awarded to a Yiddish writer.

I can still vividly recall Chaim Grade’s reaction just two days after Singer’s Nobel Prize was announced. When I mentioned those who were arguing that Grade, himself a revered Yiddish poet and novelist, was more deserving of the Nobel, he barked at me that it was his lifelong friend Abraham Sutzkever who deserved the prize. What earned Grade and Sutzkever the reverence of many Yiddish readers was that each devoted his postwar work to memorializing, indeed sanctifying, their Vilna Yiddish world destroyed by the Nazis.

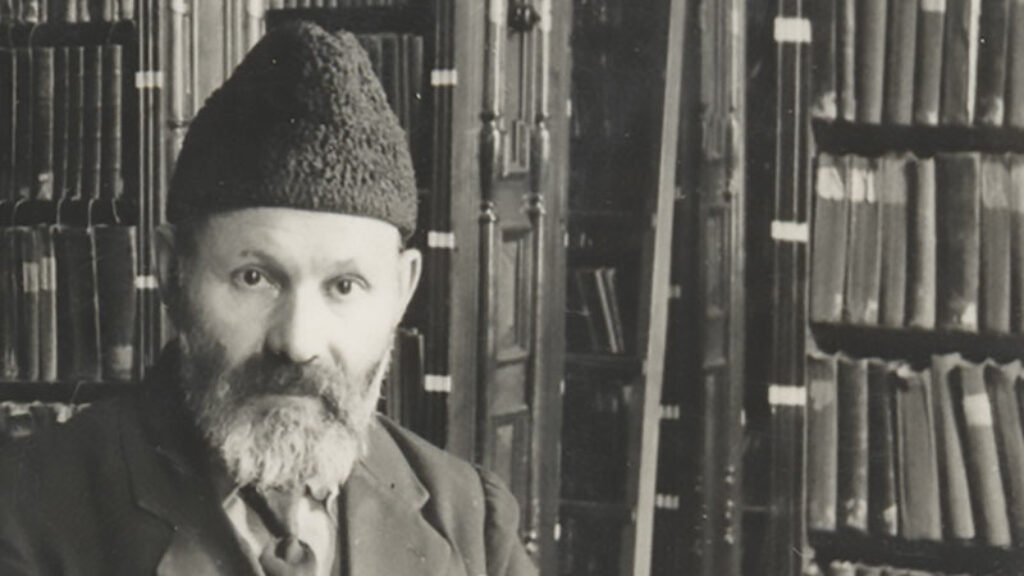

A young Abraham Sutzkever from the movie Black Honey, The Life and Poetry of Avraham Sutskever, 2018. (Courtesy of Yair Qedar and Itay Barkan.)

In 1978, almost nothing of Sutzkever’s work was available in any language other than Yiddish, while Singer was already widely available in nearly ten languages. Over the subsequent years, the great Vilna poet has, thankfully, become far more widely recognized, translated, and celebrated. The past decade alone has witnessed an unprecedented surge of English translations and scholarly studies of Sutzkever’s work, as well as two fine feature-length documentaries. The Israeli literary scholar Dan Miron recently proclaimed that Sutzkever was the greatest poet in the history of the Jewish state, surpassing more famous Hebrew-language colleagues. Yet in Israel, where Sutzkever spent the last half century of his life, he remained almost entirely unknown, and his funeral in 2010 was attended by no more than a few dozen people.

Eight years after Singer’s win, Elie Wiesel became the second great Yiddish stylist to receive a Nobel Prize, albeit for Peace (a rare commodity in Yiddish literary circles). That almost nothing has been written about Wiesel’s contribution to Yiddish letters only underscores the destiny of the work of the far less-known writers who published solely in Yiddish. Wiesel’s majestic nine-hundred-page Holocaust memoir, Un di velt hot geshvign(And The World Remained Silent), is remembered today only because the Yiddish manuscript was the source for Wiesel’s vastly condensed La Nuit, which in turn begat the first English-language Holocaust memoir, Night, earning Wiesel worldwide recognition. Meanwhile, his Yidish essays, literary reviews, and reportage for Yiddish newspapers, magazines, and journals number in the thousands, according to Israeli Yiddish scholar Yechiel Szeintuch. This vast Yiddish oeuvre by the author of The Jews of Silence itself remains shrouded in silence.

Some time ago, my friend Marion Fishman gave me a copy of the 1969 edition of an obscure Yiddish periodical called the Vilner Almanakh. Leafing through it, I was astonished to find a powerful essay by Wiesel on Sutzkever, which I had never before heard of. I searched the literature on Sutzkever for references to it but came up empty-handed, so I sent it to Yiddish scholar Ruth Wisse. Wisse was close with Sutzkever for decades, and Sutzkever shared news with her of each new article about his work, but even Wisse confessed that she had not known of this particular piece’s existence. How was it possible that a beautifully crafted and moving tribute to the greatest poet of the Holocaust, written by its most illustrious witness, has remained all but unknown, even to scholars of Yiddish literature?

The explanation almost certainly lies in this essay’s venue. The Vilner Almanakh was as rich in content as it was poor in circulation. Five issues were produced between 1968 and 1972 and were distributed to a select few survivors of the prewar Vilna Jewish community. It was a project of Yiddish theater director and writer Melech Karpinovitch, who also served as editorial board secretary of Sutzkever’s celebrated literary journal Di Goldene Keyt. While Wiesel’s frequent contributions to Der Forverts were read by its tens of thousands of subscribers, it is unlikely that more than one hundred people ever saw his dazzling essay on Sutzkever’s Lider fun yam ha-moves (Poems from the Sea of Death).

Lider fun yam ha-moves is a vast five-hundred-page collection of Sutzkever’s poetry about the Khurbn (as the Holocaust is known in Yiddish), composed over more than three decades. Wiesel’s opening challenge to literary scholars to critically analyze Sutzkever’s language, style, rhyme, and meter was clearly meant to free him from the classic constraints of a book reviewer. This essay is instead an overarching tribute to Sutzkever’s sanctification of the poem. In it, Wiesel succeeds in capturing how Sutzkever’s life-long love affair with poetry—in the Yiddish language that he loved supremely—allowed him both to survive the horrors of Nazism and to become its most elegiac eyewitness.

_______________________

Poetry too was murdered in the German death factories. So declares the German intellectual [Theodore] Adorno. His suggestion seems logical enough: how can one sing about Auschwitz, after Auschwitz? To begin with, the theme of destruction [khurbn] becomes the singular one with which one not only may, but must, deal. So then, how may one, how dare one, juxtapose poetry to it? In Auschwitz that source too was incinerated, that dream choked.

The Jewish approach is, however, different. So long as the Jewish poet remains alive, he will to his dying breath, indeed with this very last breath, spin ancient and new dreams, chanting their songs, that they might pass to future generations.

This, one might say, is the moral lesson of Sutzkever’s Poems from the Sea of Death, recently published by the World Union of Survivors of Bergen-Belsen (1968).

The author is one of the greatest poets in Yiddish—and world—literature. His work displays not only literary, but also moral, brilliance. These poems prove that, so far as Jews are concerned, Adorno is wrong; Jewish poets sang not only before the Khurbn, but also from the very heart of the inferno. The malek-hamoves (Angel of Death) had no dominion over their verse. Sutzkever created transformative works within the Ghetto walls, from deep inside the boneyard; they will certainly endure as an eternal testament about that epoch when Jewish life and Jewish blood had been robbed of all value, when humanity betrayed the Jew and, by doing so, renounced their own humanity.

So let the poets plumb the richness of Sutzkever’s images and resonances, the lyricists laud his masterful form, structure, and wondrous language; for us [Jews] his poems are remembrances of, and testimonies to, silenced truths and never-heard final confessions.

Anyone who struggles to learn what the skies and fields, the forests and the faces looked like when Jewish children were being led to the Akeyde need but open the gates to Sutzkever’s verse, if only to find a single tear from that bottomless Sea of Death so deep in horror and desperate lamentation.

This collection also includes creations from later periods; the last poem is dated 1966. Still, all these poems incorporate the Khurbn-motif. The Ghetto wraps around them like a tallis aflame. One feels this from the very first lines about a Ghetto day, with “the blind beggar [caught] in the corner of a decrepit wall, pennies weeping up his sleeve,” to the last ones about “Yortsayt for a smile, in forest and plane” and “time,frozen in Ponar [Forest].” What more may one say about such eyewitness poems than that they speak the truth, that everything is true, every word and every letter? There is not a single exaggerated line, not a single false resonance. The poet with his voice and his might then draws us much further, high beyond [their destruction] to the vanished worlds which, in his memory, remain eternally whole and holy.

Despair? Sure, there was also despair in that bizarre, damned world. Yet life is stronger, and the poem forever emerges as the champion. Sitting in a dungeon where darkness tries to stab him to death, Sutzkever chants:

I uncover a broken glass, trapped

Moonlight shines from within its imprisoned crystal

I forget the choking fever into which I’ve fallen

Behold, this was created by a human hand.

While digging his own grave, the poet notices a tiny worm, which resists being killed—even when cut into a thousand pieces, there remains a piece of life in each piece, each remains a living creation. And so if worms possess such a capacity for resistance, how much more so do humans certainly possess it? This is despair vanquished, transmigrated into verse’s eternal life.

Behold the poet standing face to face with imminent death when he notices birds in flight. And what comes to his mind’s memory? Terror? No. Regret and yearning that he has toured so few lands, drunk from so few tomes? Not those either. Rather, he realizes that he had never before noticed that when a bird flies, it creates the impression that it has four wings, not just two. The eye of the poet is mightier than the Angel of Death.

Even were he to be lying in a coffin—which Sutzkever conjures in a vision—he would never give up the game, abandon the struggle; he hears the voices and recognizes the eyes of beloved souls from near and far and declares:

This seems to be the order:

Today here, tomorrow there

Even now in a casket

Dressed in wooden clothing

My verse is still singing.

The secret to his art and the art of his creativity can be found in the book’s introduction:

When the sun seemed to me to have transformed to ash—I still believed this with complete faith: so long as the muse does not desert me, the leaden debris will never asphyxiate me; so long as I live poetically within this encirclement of death, my suffering will be resolved and will have received its Tikkun.

The renowned Jewish psychologist, Viktor Frankl, himself also a former Katsetnik [concentration camp inmate], has expressed the same thought, albeit in his own unique language and fashion. According to him, this same aspiration saved those who struggled toward its realization: which is to say that one who maintained his purpose had greater chances of surviving that Gehinnom.

The poet’s purpose was, above all else, to recall everything, to transcribe and to memorialize in words with artistic timbres, and thereby to rescue from annihilation and oblivion as many morbid phantasmagorias, as many experiences, and as many cries of death as possible.

Pick up Sutzkever’s introduction once more and read further:

I present here an account of surviving the Ghetto years, set down poetically: one who was so beaten down with such merciless savagery that it never ceased tormenting me, and from whose lashes I try to escape, gasping for air, only to fall into a watery lime-filled ditch. I lie down in the limewater, and my wounds burn as if I were lying in a bed of fire. But then suddenly I behold something singularly beautiful. My blood drips into the frozen gel and paints in the lime the image of a wondrous sunset. I forget the pain burning in my open wounds.

What he forgets is that he is at death’s door. A murderer might notice and shoot him. But the poetic experience is stronger than fear. And out of that ditch there emerges song. The lime-filled ditch becomes pleasant; just a moment before death, life becomes loved, as does this world conquered by murderers. He reflects:

So now I shan’t cease gazing

Till night, till night

At this most beautiful sunset created through my own might.

And this is the key to Sutzkever’s poetic kingdom: man must find beauty where all is foul and defiled.

Man must sing where man has, so to speak, subdued the Creator Himself. Precisely because the enemy’s goal was to asphyxiate all poetic expression in the ghettos, for this very reason the poet was so driven to set free his fantasy and his word. So, there is no one for whom to sing? What of it? Future generations will listen to my poem.

It is true that at times he is overcome by sadness: is he not now the very last poet in the world? Will his words yearn to see the light but remain in a state of endless yearning? In such moments he screams:

“Tear away from me! Depart,” my words demand.

The birds of despair soon fly away. The poet engages in prayer, despite there being no one listening, because:

Still, a prayer must there be

for those close to me, and so needy

Causing my soul such agony

Thus shall I continue to sing on

Even if senselessly, and till dawn.

“Senselessly”? Yes! What the poet sees is enough to drive him mad. He witnesses—and he depicts—the ghastly grimaces of frozen Jews, maddened musicians, tragically vanished mothers, corpses cast in fields, perplexed prophets in the Shulhoyf [the courtyard of the Great Synagogue of Vilna]. He beholds the annihilation of a people and knows that for this humanity must pay a terrible price. Indeed he envisages a dark, soulless future—his portrayals match the power of these visions, words as desolate as the darkest vision. If you wish to get a sense of his past heroes, if you want to know what became of them, do not resist. Allow him totransport you where he goes and where he storms, and remain silent during his passion-filled Kaddish.

Sutzkever’s mission is, moreover, ageless; it bears the burden of history. And historians will find in his words the stuff of the creation’s dawn, from which they were conceived.

I have often wondered whether or not poetry is the sole form capable of eternalizing the memory of the Khurbn. Neither dry prose nor pure philosophical speculation have the capacity to capture its mystery. Only poetry is capable of this. And more: Sutzkever’s work is also essential as a documentary. It portrays that Sea of Death as it was in fact experienced. One who reads Sutzkever’s verse assumes anew the burden of the Khurbn, “seeking the Shofar of the Messiah in its bloodied blades of grass and incinerated cities.”

All that now remains is our longing for the poem, and the yearning from within the poem itself—and Sutzkever is poetry’s redeemer.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Golden Books

Three decades ago, Allan Nadler went to Vilna to reclaim books that the Nazis had plundered from YIVO, or so he thought. Dan Rabinowitz’s Lost Library solves the mystery—and raises important questions.

When Heidi Met Shimen

Whereas Heidi and her woke progeny scatter in the winds of the American landscape and the heirs of Yitzy and Ben find themselves growing further apart, their Israeli counterparts find themselves socializing together, mostly serving in the army together, and sharing a Jewish cultural vocabulary.

Cultural Life in the Vilna Ghetto

The great poet Abraham Sutzkever once swore an oath to serve Yiddish culture. He fulfilled his vow in ways no one could have ever imagined.

The Poet from Vilna

Avrom Sutzkever and Max Weinreich, a memoir.

Charles Blattberg

This is excellent! A big thank you to Allan Nadler.