Nobody’s Fool

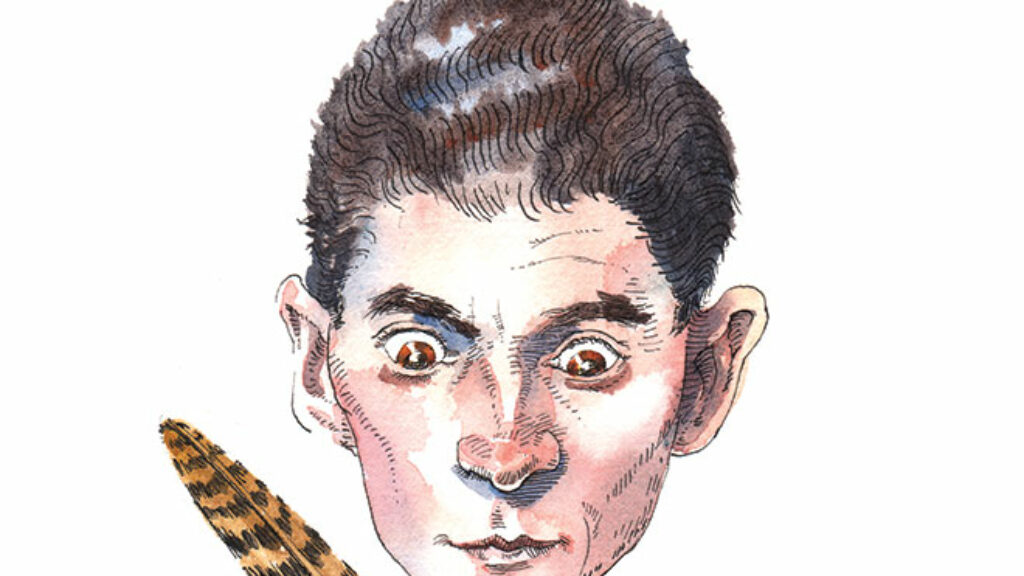

Simple Gimpl bills itself as “The Definitive Bilingual Edition” of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s signature short story. The subtitle’s portentous use of “definitive” is undone in cheeky fashion by the book’s shape and form. It is a colorful little pocket square of a paperback festooned with whimsical illustrations by Liana Finck that suggest what Marc Chagall might have produced if he were a latter-day New Yorker cartoonist. (Finck is also the author of the 2014 graphic historical novel A Bintel Brief: Love and Longing in Old New York).

The story, originally “Gimpl tam” in Yiddish, is familiar to English readers as “Gimpel the Fool,” the title Saul Bellow used for his famous 1953 translation. The new, definitive edition contains Singer’s original Yiddish text together with Bellow’s version, alongside a new translation by David Stromberg and, remarkably, Singer himself. As Stromberg explains in the afterword, in 2006 he came upon a journal containing a dramatization of the story that Singer had produced in English in the YIVO archives. The play contained about 60 percent of the original story, and eventually, Stromberg realized that he could use Singer’s text as the basis for a new and more faithful translation of “Gimpl tam.” It is not clear precisely which parts of the new translation belong to Singer and which to Stromberg, but the results read smoothly, without any obvious seams.

Originally written in 1945, Singer’s story takes the reader back to a prewar shtetl called Frampol, home of the gullible Gimpl, who is deceived by everyone, especially his faithless wife. Eventually, the Spirit of Evil appears before Gimpl and tempts him to punish the townsfolk for their mistreatment of him. When his deceased wife visits him in a dream and warns Gimpl of the agonies awaiting the sinful, Gimpl abandons his plan for revenge and leaves Frampol and its malignancies. He becomes a wandering storyteller, spinning yarns for all he meets.

Some have suggested that in exile from the malignant shtetl, Gimpl becomes a figure for Singer himself. What seemed at the story’s outset as woeful naivete becomes by the end a principled mode of life, a refusal to be conquered by cynicism. This original Gimpl is, arguably, a more complex figure than the holy fool of Bellow’s bravura translation.

Part of Stromberg’s fascination with Singer’s story comes from the famous metastory of its first appearance in English. In the early 1950s, the literary critic Irving Howe teamed up with Yiddish poet Eliezer, or “Lazer,” Greenberg to translate Yiddish stories into English for what would become their landmark A Treasury of Yiddish Stories, and they convinced Bellow to help them one afternoon. As Howe later remembered it:

I inveigled Saul Bellow, not quite so famous yet, to do the translation. . . . Bellow had a pretty good command of Yiddish, but not quite enough to do the story on his own. So we sat him down before a typewriter in Lazer’s apartment on East Nineteenth Street, Lazer read out the Yiddish sentence by sentence, Saul occasionally asked about refinements of meaning, and I watched in a state of high enchantment. Three or four hours, and it was done. Saul took another half hour to go over the translation and then, excited, read aloud the version that has since become famous. It was a feat of virtuosity, and we drank a schnapps to celebrate.

Bellow’s version of Singer’s story was immediately published in Partisan Review; a year later it reappeared in Howe and Greenberg’s anthology.

The problem with this picture, as Stromberg points out, is that the three men responsible for this translation never consulted with Singer himself. “Bellow, Greenberg, and Howe celebrated their ‘feat,’” Stromberg writes in his afterword, “without considering what Singer—a living author who had been intimately involved in the translation of his first novel into English—might have to say.” As dazzling as Bellow’s version may be, it takes certain liberties that obscure Singer’s original intentions. Although Singer knew that Bellow’s translation was his first great break into American literary culture, he also appears to have realized its flaws, many of which were corrected in his own, albeit partial, English version of the story.

The new version, begun by Singer and completed by Stromberg, tends to be less wordy and more idiomatic than Bellow’s. When we first meet Elka, Gimpl’s wife, Bellow’s version reads, “Her mouth would open as if it were on a hinge, and she had a fierce tongue.” This captures the sense of the Yiddish original, but the prose is a little stilted, as if Gimpl were straining to make sense of his impressions. By contrast, Singer-Stromberg compress this line to “she had a mouth that moved a mile a minute,” which better sustains the illusion of fluent oral speech.

At the same time, the new spelling of the protagonist’s name, written according to YIVO transliteration rules, looks odd in English, making the reader constantly aware of its foreign origins. As for “simple,” this is more accurate than Bellow’s “fool” as a translation of “tam.” Tam, which entered Yiddish from biblical and rabbinic Hebrew, carries a range of meanings from innocent to guileless. In the Bible, both Jacob and Job—rather different characters, to be sure—are described by the word. Those familiar with the haggadah will recall that the third of the four sons who inquires about the seder is named tam, which is rendered in most English haggadahs as “simple.” Thus, Stromberg establishes a connection between Singer’s protagonist and this third son who asks his sincere, childlike question at every Passover seder. (For his part, Bellow may have chosen “fool” because of his close reading of Dostoyevsky, whose holy fools are far from the seder’s simple son.)

In Bellow’s translation, a number of words, phrases, and sometimes entire sentences were omitted. Stromberg has restored several of these omissions, giving Gimpl some gems of which earlier English readers were deprived. For instance, when Gimpl is fooled into believing a dog was barking at him, he tells the reader that it turned out to be Wolf Leyb the Thief, adding the phrase “olev hashnobl.” This is a play on the Yiddish phrase “olev hasholem,” meaning “may he rest in peace.” Gimpl has replaced “sholem” (peace) with “shnobl” (nose). A literal translation would sound strange in English because “peace” and “nose” sound dissimilar. Bellow simply gave up on the line, but in the new translation, Gimpl says, “May he rest in pieces,” which is similarly deft and funny.

Another restored passage comes when Gimpl discovers his wife has given birth to a child seventeen weeks after their marriage (and, it would seem, without its consummation). After pondering this mysterious birth, Gimpl throws up his hands and declares, “On the other hand, who knows? After all, they say that little baby Jesus had no father at all.” Bellow, Howe, and Greenberg would have been well aware that Gimpl’s hint of incredulity reflects a deeply irreverent and defensively anti-Christian tradition within Yiddish culture. Perhaps, their urbane sophistication notwithstanding, they considered this an untranslatable embarrassment. But how wonderful to hear Gimpl say this! While showing us a Gimpl gullible enough to countenance even the idea of the virgin birth, it suggests that after all, Gimpl may be nobody’s fool at all.

The art of translation is often regarded suspiciously: we’re only getting an approximation of the original, like kissing the bride through a veil, as Bialik is supposed to have said about translations of the Bible. In the case of Yiddish, as scholar and translator Anita Norich has observed, the idea that translations invariably miss the mark can seem particularly tragic. Today there are relatively few people who read Yiddish literature in the original. Those among the ultra-Orthodox who do speak the language have little interest in a writer like Isaac Bashevis Singer, and although the number of non-Orthodox Yiddishists is growing, it will never approach the Yiddish audience that existed before the Holocaust. But if a translation is virtually the only way a text is ever accessed, it can come to seem disturbingly like an epitaph, a sign that a vibrant culture once existed but is no more. Stromberg’s bilingual edition attempts to avoid this fate by making sure that we never lose sight, literally, of the original. Moreover, by including two translations, the reader is invited to triangulate, flipping back and forth between the translations and the original to recapture and savor the nuances and tone of Singer’s original Yiddish.

To me, Stromberg-Singer’s Gimpl sounds more playful and joyous than Bellow-Singer’s holy fool. I would never abandon Bellow’s classic translation, which is the result of a unique and fortuitous moment in literary history in which two Jewish Nobel laureates both did and did not collaborate, but Stromberg never suggests that we must do so. His edition is “definitive” precisely in declining to make such demands.

With regard to this question and much else, we would do well to recall Gimpl’s own words: “Of course the world is a world of lies. But it’s one step from the true world.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Storytelling, or: Yiddish in America

The basic recipe of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s later novels called for a guy with two wives or lovers who ping-pongs between them for a couple of hundred pages and then runs away. And yet this new collection of Singer’s essays, reminds us that he was not only a great storyteller, but a great champion of the importance of stories for art and for life.

“Love Between Writers”: Saul Bellow and Bette Howland

“I thought you knew that I belonged to the Truth Party too,” Bette Howland wrote her fellow novelist, mentor, and sometime lover, Saul Bellow. Her son recently found a new cache of letters between them that illuminates two brilliant artists at work.

In the Beginning, There Was Angst

Where a committed secularist would raise up the literary in place of the sacred, Adam Kirsch’s discussions in The Blessing and the Curse read more like a coda to the sacred scriptures.

From King James to Koren

The new Koren Tanakh smoothly addresses some thorny questions of biblical translation, including this one: Are there dolphins in the Torah?

David A. Kessler

I enjoyed the review, but the last line left me wondering if you had missed the intent of the quoted line and sure that most readers would. “The world of truth” - Olam ha-emes - is a reference to the afterlife, where you reside after your sojourn in this world - and while there it is true that lies are absent, so inevitably is life itself.

gershon Hepner

Gimpel the Fool, Don Quixote and the haggadah

Bashevis Singer’s Gimpel, unlike Cervantes’ Don Quixote,

is Ashkenazi, not Sephardi. Both were rather weird.

Don Quixote, windmills facing, wears a gentile goatee,

Gimpel, fooled by facts of Jewish history, by it queered

Don Quixote, unwise hero, at windmills wants to tilt,

Gimpel we laugh at is a fool, like one of the haggadah’s

sons who asks “What’s this?” not sharing his bad brother’s guilt,

a man of whom dissenters of his views are not discarders.

Gimpel’s author won for stories that he wrote the Nobel;

two years before Bellow, who translated Gimpel’s Yiddish.

Haggadah’s fourth son, since he asked no questions, just like Job‘ll

deserve it too, the master of the stiff lip--very British.

Too late for him to win this prize, just like the afikoman,

which like the festive sacrifice should not be eaten after midnight.

Those questions we can’t answer we must guard like noble yeomen,

protecting them from answers that are hardly ever right.