The Beginning of Politics

“Treat a work of art like a prince,” Schopenhauer advised. “Let it speak to you first.” Leon Kass is all ears. He assumes “that Exodus is a book, an integrated whole, with a coherent order and plan”—not just, as most academic Bible scholars since the 19th century have assumed, “a collection of stitched-together fragments from different sources.” He approaches the text with many questions but few assumptions, trying deliberately “to read it as if for the first time, ignorant of what happens later in the story,” for “to appreciate something as a gift, we must be able to experience it as a surprise.” He is confident that “like any great book read often and openly, Exodus will eventually show us how it wants to be read.” That use of the first-person plural is crucial because Kass converses throughout not just with the text and his readers but with a varied group of study partners: relatives, students, friends, and a handful of biblical commentators, including Rashi, Umberto Cassuto, and Robert Alter. In this shared inquiry, a community of teaching and learning coalesces, in high leisure Shabbat study mode, around the foundational book of the Jewish people.

But Exodus wants not merely to be heard but to be heeded—understood in soul-forming ways. Kass responds to this imperative with a keen sense of the spiritual and political drama of Exodus. He registers in warm, clear prose the rich resonances and emotional and intellectual tones of the book’s essential events and themes.

As he tells us in his charming preface, Kass came to the Bible relatively late, and his commentary is, he says, a “work of my old age.” Raised in a “Yiddish-speaking and proudly Jewish” home, he was taught to cherish human dignity and yearn for justice (he and his wife, Amy, would later volunteer as civil rights workers in Mississippi). Yet he never read the Bible in his youth, had no bar mitzvah, and entered college expecting that religious superstition would someday yield to Enlightenment reason and Kantian morality. By the time he began his teaching career at St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1972, Kass had earned an MD and a PhD and published articles and essays in biochemistry and biomedical ethics. Tutoring “Johnnies” deepened and broadened his knowledge of the Western tradition but left him hungry for something more than science, philosophy, and poetry could provide. What he was looking for fell into his lap when he began to teach Genesis in a common-core freshman course at the University of Chicago. That experience would eventually lead to his influential commentary The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis. “Given where I started out in life,” he muses in the introduction to Founding God’s Nation, “I am amazed to be finishing it so deeply engaged with the Hebrew Bible.”

Kass’s interpretive sensibilities are evident in his account of Moses’s first encounter with God. Having fled Pharaoh’s palace for the fields of Midian after murdering a brutal Egyptian taskmaster, Moses, initially “a stranger in a strange land” (2:22), seems to have settled down. He has married, become a father, and found employment as a shepherd in the service of his father-in-law, Jethro. But he is inwardly unsettled and ready, Kass writes, for “a journey to a numinous experience.” Wandering in the desert, “very likely . . . [feeling] estranged and restless, psychically and physically searching,” he takes his flocks “‘beyond’ (or ‘behind’) the wilderness (or perhaps ‘the pasture’; ’achar hammidbar), and he came to the mountain of God (har ha’elohim), unto Horeb.” (3:1) There he encounters the burning bush.

And an angel (or “messenger”; mal’akh) of the Lord appeared unto him in a flame of fire out of the midst of a thorn bush (sneh); and he looked, and, behold, the thorn bush [was] burning with fire, but the thorn bush was not consumed. And Moses said [to himself]: “I will turn aside now and I will see this great sight, why (maddu‘a) the bush is not burned?” And [when] the Lord saw that he turned aside to see, then God called unto him out of the midst of the bush, and He said: “Moses, Moses”; and he said: “Here am I (hinneni).” And He said: “Do not come closer: put off your shoes from off your feet, for the place upon which you stand [is] holy ground (’admath-qodesh).” And He said: “I [am] the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob”; and Moses hid his face: for he feared to look upon God. (3:2–6; emphasis added)

What sort of fire—what sort of shrub—is this? And what to make of Moses’s wonder—his turning away from shepherding, that is from “a matter of leadership and rule, toward questioning and understanding, a matter of truth, to be sought for its own sake”? Is, Kass asks, his wisdom seeking “a prerequisite for his mission, one that will then be properly elevated and redirected? Or does it reflect a character trait that must be corrected or even squelched?”

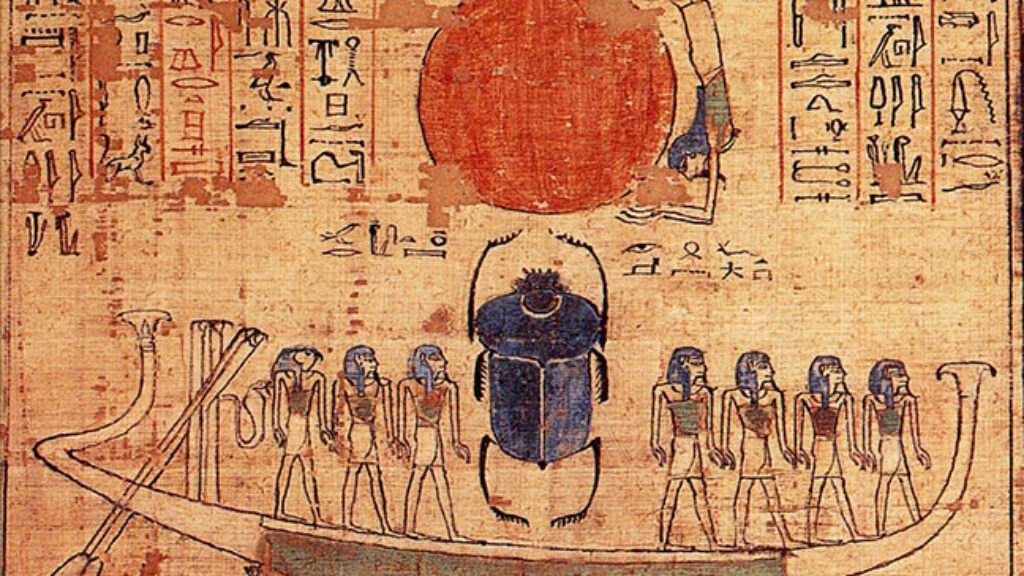

The bush, Kass notes, displays something like the pure energeia or “luminous and seemingly self-sustaining” actuality that the Egyptians associated with the sun god and Aristotle later regarded as essential to divinity. The burning bush seems to be “at least an image, if not an actual terrestrial instance, of the eternal and the divine.” But while this astonishing phenomenon catches Moses’s eye, God, who “generally knows how to appeal to His customers,” uses philosophical wonder to bring Moses into religious awe. The bush speaks, and Moses hearkens to a voice. Adrift in the remotest wasteland, Moses finds himself (“Here am I,” hinneni) on the firm and sacred ground of patriarchal tradition, where Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob took their stand in the presence of their God. “Moses approached wide-eyed to see a natural sight, in Egyptian wonder, but shrinks from seeing his father’s God, in Hebraic awe.”

Kass’s moving description of Hebraic awe (yir’ah) reflects an immersion in Jewish ways of feeling and thinking that seems, if anything, to have deepened in the years since he wrote on Genesis:

Awe-fear-reverence is not a congenial passion: it implies, and insists on maintaining, clear distance from the object that elicits it. It acknowledges our weakness and inadequacy before something much greater than ourselves (“do not come closer”; “put off your shoes”). And yet it does not—like simple fear or terror—lead us to flee. On the contrary, despite the evident inequality, the very fact of our recognizing the superiority of the object builds a connection between us. We are both attracted and repelled; we want both to approach and to stand back; we oscillate in place, bound in relation to the thing that defies our comprehension and makes us feel small. . . . Paradoxically, thanks to awe-fear-reverence and the bond it builds across the unbridgeable divide, we also feel less small. We are, in fact, lifted up, enlarged, magnified.

As Kass reads the episode of the burning bush, piety and obedience do not require one to turn away from philosophical wonder. Indeed, “for leadership in God’s Way, interest in the universal truth of things is every bit as important as fellow feeling, concern for justice, and the love of your own people.” Moses does, after all, commune with God atop Sinai for 40 days—an extended, purely intellectual encounter (signaled by Moses’s complete abstention from food). Yet philosophy is insufficient to know God or to lead His people, as God’s enigmatic name, revealed on the bush’s sacred ground, implies. “I will be what I will be” suggests the “acting in time”—the italics are Kass’s—of an “ongoing, progressing, free, and unpredictable” being. God can be known only by attending to what He reveals of Himself in covenantal partnership with His people; adequate knowledge of God and man alike is achieved not in speculative thought but in the revelatory drama of covenantal history.

In his talmudic commentaries, Emmanuel Levinas sought to translate “Hebrew”—Jewish wisdom—into “Greek,” the common language of the West. Kass undertakes a similar project in his biblical commentaries, which illuminate a vital part of the Jewish tradition that Levinas, for all his ethical and theological depth, neglects: the prophetic political teaching of the Bible.

The stories that unfold in Genesis, Kass writes, “quietly convey an anthropology . . . that shows us why human life, if left to its own devices, leads to disaster.” The patterns and rhythms of untutored human experience are quickly established east of Eden. From Cain on down, the blood-soaked ground of exile cries out for cleansing; reversing the creation, God opens the wellsprings and casements that hold back the perilous waters. Scattered and shaken by distant memories of the great deluge, the protomodern Babylonians build a high tower on low but not-so-solid ground. Whereas God breathed life into the soil (adamah) to fashion the human being (adam), the Babylonians pack and bake the earth into uniform bricks fit for stacking, made and measured according to one human logos. In what Kass aptly calls the capstone of the universal human story, the people of Babel make themselves into bricks; the living image of God, reflected in the speech and deed of human individuals, is buried in the engineered mass of the social edifice.

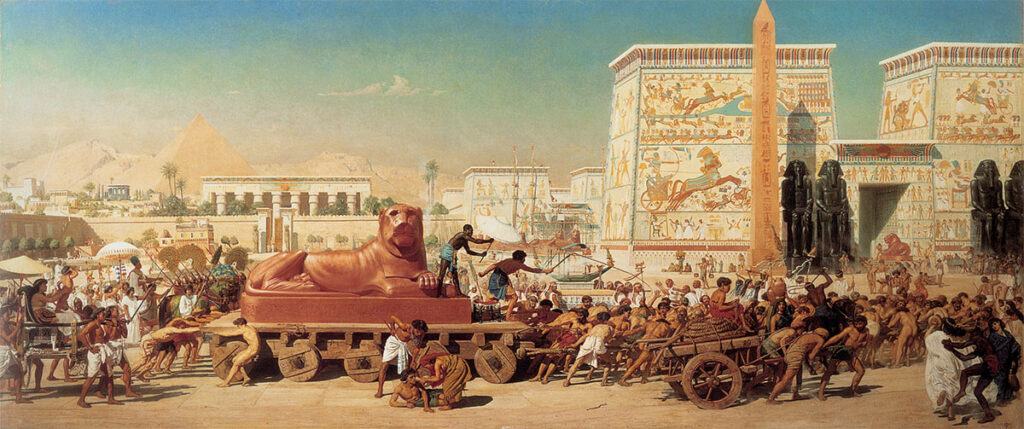

The basic themes in the universal history of Genesis 1–11 are reprised in Exodus. When we meet the Israelites, they are making many bricks under the taskmaster’s lash to build storage cities for grain. The new pharaoh may not know Joseph, but it was under his administration that an old one centralized pharaonic power. By the time of Moses, Egypt has become a scientifically advanced and administratively sophisticated Babel sustained by the labor of slaves. Kass observes that Sobek, the god of crocodiles, symbolized pharaonic strength and military power: Pharaoh masters chaos as the reptile king masters the malarial waters of the Nile. In Egypt, pride and the fear of instability extend beyond the impressive solidity of megalithic tombs to the attempt to control Hebrew birth by infanticide and to overcome Egyptian death by medicine, embalming, and religious magic.

In Babel, political speech is drowned out by one universal tongue; in Egypt, where God’s image is so thoroughly effaced that He and the children of Israel forget about each other for four centuries, it is swallowed up by the dead letter of clever, crocodilian managerialism. In Egypt, a world of total work, there is no pause for restoration and thanksgiving, no sacred time-out-of-time, no Shabbat. From where we stand today, it is perhaps not hard to believe that this really is, as Kass writes, “the peak of civilization and the highest human possibility that knows not the God of the Bible.”

Egyptian despotism deforms bodies as well as souls: Kass observes in his study of Genesis that Pharaoh’s highest servants were eunuchs. In fact, the casual mutilation or deformation of human life—of bodies and souls, families and political communities—is the fundamental problem of Exodus. And it is in thinking through this problem in the light of his earlier study of Genesis that Kass implicitly uncovers a teaching of stunning importance. He suggests that the lands between which the Israelites wander for 40 years are not just places but opposed civilizational extremes, each of which feeds on the other: hyperrational, Apollonian Egypt and the chaotic, Dionysian Canaan exemplified by the stories of Shechem and Sodom.

But Kass also reveals the ground of hope in Exodus. He helps us grasp that the liberation of slaves as a people under the biblical God is more than the founding story of an ancient nation that has endured now for more than three millennia. It is a universal and permanent human possibility. Kass shows how the way of life that emerges in Exodus fashions a society uniquely suited to human beings by preserving the imperfect, much-maligned, and always imperiled image of God in this world.

“Even atheists,” Kass writes, “must have an idea of the God in Whom they do not believe.” In Exodus, there are several gods that do not merit belief. The golden calf is one of them. The impotent and rage-maddened Pharaoh is another. Who could believe in him and his priests after the natural world they worship and seek to control by magic, science, technical skill, and political force—the waters, earth, sky, and all living things; the heavens and “the sun itself”—revert to chaos in the 10 plagues?

But in Exodus, there is also one God in whom mature adults can and do believe. Kass shows that God emerges in the mysterious middle ground between human agency and divine assistance. The hardening of Pharaoh’s heart so that he stays “true to himself to the bitter end” in the face of the plagues is part of God’s plan, but it is also a natural consequence of a nature so puffed up with pride.

Moses learns to trust God, and the people Moses, but Moses trusts the people too little, and they make the same mistake with God. Modeling what is needed, God is the first to lay out His bona fides for all, not just in the high drama of Exodus but also in the law He delivers at Sinai amid smoke and thunder (a logos or “speech with teeth,” as Kass finely puts it) and the plans for the tabernacle and the priesthood He reveals to Moses atop the mountain. In all of this, He aims to educate, elevate, and contain the impulses, including those of Moses, that might otherwise lead His people astray.

Kass’s reflections on Moses’s political strengths and weaknesses significantly extend the insights of Aaron Wildavsky’s classic study The Nursing Father: Moses as Political Leader. He demonstrates, for instance, the signal importance of the prologue to a ceremony of sacrifice designed to ratify the Sinaitic covenant, one that Moses arranges on his own initiative:

And Moses took (vayyiqqach) half of the blood, and put it in basins; and half of the blood he threw (zaraq) against (or “upon”; ‘al) the altar. And he took (vayyiqqach) the book of the covenant (sefer habberith), and read it in the hearing of the people; and they said: “All that the Lord has spoken will we do and we will obey” (or “hear”; na‘aseh venishma‘). And Moses took (vayyiqqach) the blood, and threw (vayyizroq) it on the people, and said: “Behold the blood of the covenant, which the Lord has made [literally, “cut”; karath] with you regarding all these words.” (24:6–8)

Moses’s reading of the book of the covenant (whatever that might be) and the people’s enthusiastic answer are “sandwiched between two deeds of strewing blood.” Kass wonders, along with the traditional commentators, what is meant by the people’s addition of “we will hear” (or obey) to their previous affirmation that “we will do” (24:3). Shouldn’t hearing come first? But he is most interested in what Moses does with the blood and why he does it. He rejects the idea, propounded by squeamish translators, that Moses sprinkled the blood. Rather, “he threw it widely and broadly. . . . We can imagine blood flying in all directions. The scene is anything but decorous.” He also pushes back against Robert Alter’s attempt to connect this episode with the blood of circumcision in Midian and the blood of the lamb on the doorposts in Egypt, both of which warded off death. Kass finds Moses’s behavior “disquieting and weird,” and in this weirdness he finds a hint.

Kass shrewdly intuits that Moses’s blood strewing reflects his distance from and impatience with the people he leads. Moses relates to God on the “high plane of intellect” and has no need for signs, wonders, or sacrifices; He is annoyed by the people’s “corporeal neediness and fickle ways.” What they need is a dramatic gesture. Imagining Moses’s interior dialogue, Kass writes, “Blood . . . that will impress them, that will unite them, that will awe and inspire them.” Kass respects Moses’s instincts but doubts his wisdom in this case. This crude and gory scene is inconsistent with “a covenantal way of life that teaches order and measure, and that opposes exactly this human penchant for wildness and violence.” Moses “overdoes it” in arousing passions that tend toward “wildness and violence” and that previously burst forth in the Dionysian dance of Miriam and the women after the victory at the Sea of Reeds—a judgment supported, Kass notes, by the fact that we next see the people in the episode of the golden calf.

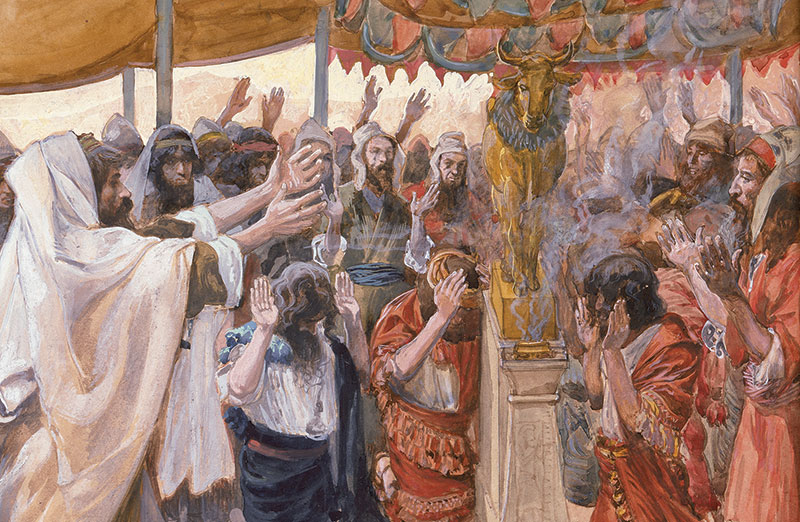

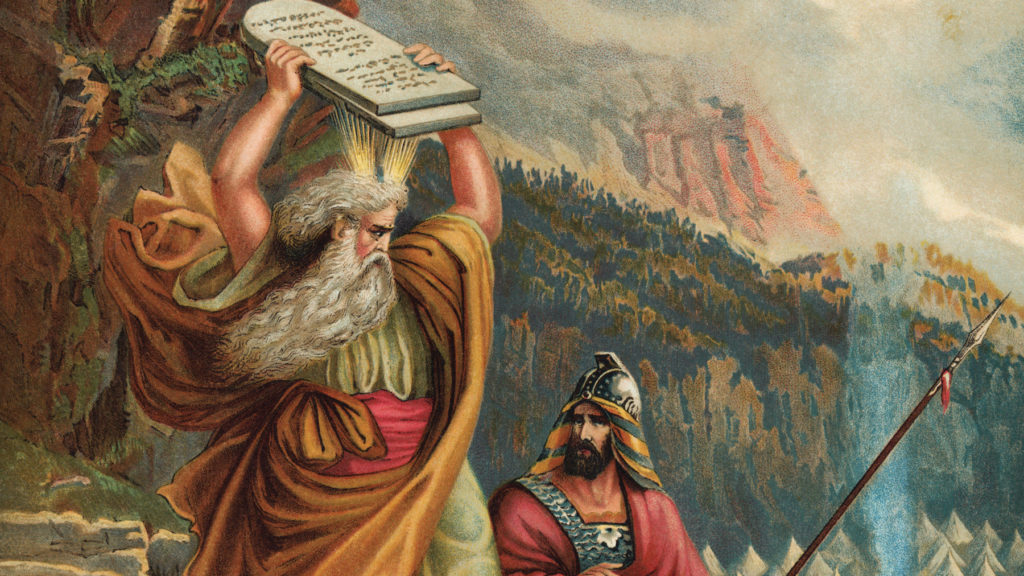

Kass has more to say about the crisis precipitated by the calf than about its making, a few words about which might be in order here. Rashi writes that Aaron shaped the dumb idol, fashioned of gold taken from the Egyptians, and intended for the decoration of the tabernacle, with a tool “like the stylus used by a scribe.” Aaron’s work is a distortion of what is happening high on Sinai, where the living God communes with Moses and writes on stone tablets. Before Moses can publish that divine word, the Israelite mob furnishes a weird, ventriloquized authorization of their amalgamated deity. “These are your gods . . . who brought you up from the land of Egypt” (32:4) twists the pronouncement that introduces the Decalogue, “I am the Lord your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt” (20:2), to make it say, “You delivered yourselves from bondage.” An egel, Kass explains, is a young and vigorous ox, “an image of natural potency and virility.” This point is brought home by God’s description of the Israelites as stiff-necked, “an ox that will not take the yoke.” Unshackled, the people indulge themselves in the next day’s Canaanite bacchanalia.

Moses responds with great physical force, angrily shattering the tablets and spattering more blood—much more. Resorting to physical and political “shock therapy,” he rouses the Levites to slay three thousand of their brothers. Kass notes that this is a political purge, not justice, for the Levites were not free of guilt: “All the people brought their gold earrings to Aaron, and . . . [participated] in the wild festival the next day.” The grisly catharsis—to which God, being a political realist, does not object—restores order but casts “a lingering stain of iniquity” over Moses and the people alike. Still in its infancy, God’s nation has already hit rock bottom.

Could there be divine method in this human madness? Kass proposes something “nearly unbelievable”: that this tremendous moral and political crisis might have been not only inevitable but necessary, even desirable. Previously, he reasons, the “frightened, slavish souls” of the Israelites were incapable of entering into “a properly executed covenant.” Their “first true act of national freedom,” the demand that Aaron make new gods, prepares them to choose God in a more mature, informed way:

Through acting freely on their own, they were able to experience responsibility, sin, and guilt; suffer estrangement from God; and feel the need for repentance and forgiveness. These experiences made them eager for and receptive to a merciful and forgiving God. . . . Only after falling away and being forgiven can the people freely and knowingly return to embrace the (renewed) covenant with the Lord.

God soon reveals to Moses just what he and the nation need to hear: “I will be gracious to whom I will be gracious, and will show mercy on whom I will show mercy.” Chastened and humbled, the people finally show their sincerity by pouring themselves into the construction of the tabernacle.

In Kass’s estimation, the tabernacle occupies “an indispensable place in the definition and national purpose of the Israelites,” equal to the liberation from Egypt and the giving of the law. The tabernacle is, above all, a locus of sacred encounters. The daily sacrifices at the Altar of Burnt Offering are intended to keep alive the people’s association with God—for “if God’s Presence is unnoticed, unknown, or unacknowledged, He is not Present.”

In the ritual of sacrifice, the popular “impulses to bloodshed, wildness, and chaos” that burst forth in the episode of the golden calf are allowed expression “under strict rule and measure.” Other rituals, like the burning of incense that wafts up in a cloud from the golden altar (“an emblem of—and response to—the invisible Presence of the Lord”), contain and elevate the inclinations of the priestly and artistic elite, including “the pride incident to their status and work.” The fully portable tabernacle, a decorously ordered whole where animals are slaughtered and burnt, is both a microcosm and completion of creation. It is the sanctified ground where the Jewish people—now unified in and purified by sin, forgiveness, and collective labor—may encounter the God who transcends both space and time but who accompanies them “throughout all their journeys”: the last, hopeful words of Exodus.

Kass concludes his study by remarking that Exodus deserves the most serious attention of “loyal yet worried” citizens who seek to navigate “these confused and dangerous times.” Yet his book leaves us with a lasting impression not of crisis and apprehension but of grace and gratitude. For he discovers in Exodus an unexpected surplus of “more-than-philosophical answers” that nourish previously unacknowledged “longings of the soul,” and he celebrates these gifts with the quiet confidence of one who has come, in the fullness of time, to appreciate the blessedness of belonging to the chosen people.

Kass shows almost as much as he says about how Exodus forms the sympathies, elevates the sensibilities, cements the community, and graces the days of those who come together to explore its meaning and live in its light. He happily and frequently acknowledges the insights of his students and study partners, including his wife, Amy, and his granddaughter Hannah, whose “offer to study Torah with me,” he movingly writes, “restored me to life in the wake of my dear Amy’s passing.” That is only to be expected. For as Kass so ably reminds us, the Torah is, after all, a tree of life.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Law in the Desert

Studying the weekly portion with Jerome, Nachmanides, and others, the seemingly tedious parts of Exodus become compelling.

Robert Alter’s Bible: A Symposium

In the 14 years since he published the Five Books of Moses, Alter has steadily progressed through the Tanakh, producing translations that aim at something like a 21st-century American equivalent of what he has called the “simple yet grand” English of the King James Version, while attending closely to the literary techniques of the Hebrew text. We asked a learned, eclectic group of six critics to discuss the results.

Exodus and Consciousness

Who left Egypt ? And how did the Israelites experience God? Richard Friedman is a biblical detective, James Kugel is more of a literary anthropologist.

Exodus and Egyptology

The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel shows why the plagues were chosen and how the Israelites sang at the reed sea.

Ronna Burger

Jacob Howland offers a beautiful, informative, and moving reflection, so attuned to the powerful reading of Exodus by Leon Kass!