An Indian Play in Warsaw

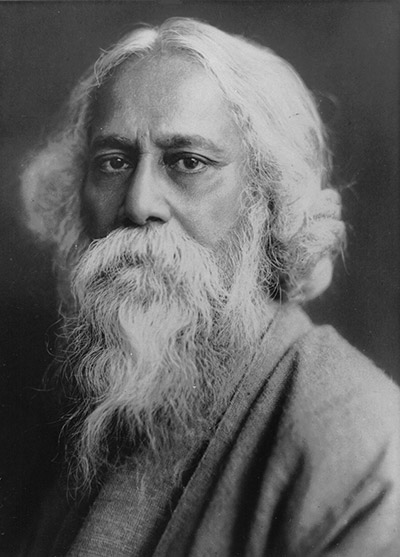

Four days before the beginning of the Great Deportation of Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto, on July 18, 1942, the inhabitants of its orphanage staged a play. Dak Ghar (The Post Office), written by the Bengali poet-philosopher Rabindranath Tagore, was chosen for the children by Janusz Korczak, the orphanage’s famous director. It tells the story of a dying orphan boy who is shut away from the world due to serious illness and must learn to live instead through his imagination. Korczak reportedly hoped the play would help the children learn to face death with equanimity.

No children survived the liquidation of Korczak’s orphanage. Almost two hundred, along with about ten of their caretakers and Korczak himself, were deported to Treblinka. Jai Chakrabarti’s debut novel, A Play for the End of the World, follows a fictional survivor of Korczak’s orphanage who travels to rural India in 1972 to help a group of refugees stage the same Tagore play and rescue their village from destruction.

How exactly this journey unfolds is the main subject of Chakrabarti’s novel, which jumps frenetically between time periods, geographies, and a half-dozen points of view. One chapter examines 1940s Warsaw through the eyes of young Jaryk Smith, the book’s orphan hero, as he prepares to perform the lead role in the Tagore play. Another is set in the New York City of 1972, following the adult Jaryk’s lover, the North Carolina–born Lucy Gardner, through her rounds at the city employment agency. Still others take place that same year in India, which is in political disarray due to a harsh government crackdown on militant Maoist groups and a recent influx of refugees from Bangladesh.

These diverse chapters are supposed to be united by common threads and themes—Jaryk’s geographical and emotional journey from fearful Warsaw orphan to Indian village savior, the twice-staged Tagore play, the tension between ethical duty and personal obligation, and the role of art in a violent world. But really, their most common element is a persistent eschewal of historical, personal, and moral complexity in favor of clichés and sentimentality.

Consider the best parts of this book, the scenes set in 1940s Warsaw, which are reasonably well researched and populated with characters and details—like the children’s court and orphanage newspaper—culled from Korczak biographies and his ghetto diaries. There is Madam Stefa (Stefania Wilczyńska), the orphanage’s strict but beloved mother figure; the apprentice teacher Esterka Winogron, who directed The Post Office; and the orchestrator of it all, Janusz Korczak, known to the children in his care by the uniquely Polish “Pan Doktor.” Chakrabarti neatly dramatizes the children’s struggles, such as a chronic lack of food in the orphanage, which he shows in a scene that has Korczak slicing meat so thin that he accidentally cuts his thumb.

Occasionally, in these sections, as in the book’s opening lines, Chakrabarti’s prose even approaches lyricism:

The set has been assembled. A piece of cawed wood that is to mean window. A watercolor Hanna has painted of the sun that is to mean sun. A bed they’ve borrowed from the boys’ dorm—no easy feat dragging it up and down the stairs for each rehearsal—that is to mean child’s bed. Wooden blocks Misha carved to mean child’s toys. And nine-year-old Jaryk is dressed like a boy from India, at least what they’d imagined a boy from India would look like: a pillowcase fashioned into a turban, a prayer marking on his forehead.

But in a hint of what is to come, even these Warsaw chapters often skim over the surface of the orphanage’s harsher realities. They depict an idealized Pan Doktor, largely devoid of personality and entirely of vice (the historical Korczak, though saintly, was still a man, and he had a taste for vodka and sometimes displayed a temper). And they eschew the most horrible truths about life in the Warsaw Ghetto orphanage, such as the occasional banishment of uncontrollable children and the fact that little beyond Korczak himself prevented those he watched over from joining the emaciated boys and girls who lay frozen to death in the ghetto’s gutters just outside the building’s walls. Even the children’s orphanage diaries are sanitized in Chakrabarti’s version. Here is Jaryk’s:

I am a little sorry I hit Mordechai not a lot just a little.

If a dog has no food it dies even Old Dog with no food so I see his face all the time.

Last night Madam Stefa comb my hair one hundred times before bed I dream white corn the Old Dog.

Do you think Pan Doktor Old Dog will come back?

Compare this with the following passage from Betty Jean Lifton’s biography of Korczak, The King of Children:

Korczak encouraged all the orphans to keep a diary like his, hoping it would help them master their feelings. . . . Yet the seriousness of their diaries hurt him. Marcel vowed to give fifteen groszy to the poor in thanks for the penknife he had found. Szlama wrote about a widow who sat home weeping as she waited for her smuggler son to bring something home from across the wall; she did not know that a German policeman “had shot him dead.” . . . Mietek wanted a binding for the prayer book that his dead brother had received from Palestine for his bar mitzvah. Sami bought some nails for twenty groszy and was counting his future expenses. Jakob had written a poem about Moses. Abus wrote: “If I sit a bit longer on the toilet, someone says I’m selfish. And I want to be liked by the others.”

The real concerns of children in the orphanage, in other words, were both far darker and more practical than those of Chakrabarti’s imagined orphan child, who confronts death through the mortality of a dog, as if he is not a boy surrounded by it.

In 1972, Jaryk Smith, the child who fretted in his diary about Old Dog’s immortal soul, has long since grown up and settled in New York, where he’s spent thirty or so years trying to forget the past. He’s in a relationship with Lucy, has a steady job as a synagogue bookkeeper, and remains close with the only other person who escaped the fate of Korczak’s orphanage, a junior carpenter named Misha.

But again, there seems to be an odd mismatch between the historical setting and the world as Chakrabarti writes it. In Chakrabarti’s 1970s New York, characters are forever performing kindnesses of the sort one might expect from a Boy Scout—helping elderly women cross the street or returning a lost child to his mother. The city seems inhabited only by men like the dockworkers Jaryk sometimes plays ball with, men so tenderhearted that they spend their free time seeding the field of a public park. Or men, like Jaryk, who weep during the third act of La Bohème.

This New York—or maybe it’s this America—seems like a softer, kinder place than the one with which the rest of us are familiar. Financially, it’s almost frictionless: all the characters painlessly afford dinners out, their own Manhattan apartments, and even answering machines (something of a luxury technology in 1972). And little things like religious differences and prejudice seem foreign to it—it never seems to occur to Lucy, for example, that her Baptist faith might complicate a relationship with Jaryk. Nor, more tellingly perhaps, does it occur to her that her father—a resident of Mebane, North Carolina (a place where “Jews had been a foreign country”), who had warned her about the city, saying, “All that sin can’t keep going on”—would ever object to her Jewish boyfriend. It’s the sort of thing that, in the sweetened world of Chakrabarti’s novel, simply doesn’t come up.

In fact, the characters are all so kind and generally genial and contented with their lives that Chakrabarti has to tie himself in knots to get them to do much of anything. External events and a heavy authorial hand dictate almost every move of this plodding novel, and characters’ explanations of their own motivations often read as slipshod and unpersuasive, or even just confusing.

Consider, for example, why Jaryk goes to India in the first place. Originally, he and Misha had been invited by an Indian professor, who hopes that the publicity generated from a performance of The Post Office may help save a village of Bangladeshi refugees, who are being threatened with displacement by a corrupt government. Misha agrees enthusiastically (“‘We can help,’ Misha said. ‘The play meant so much to us. Finally, we can pass that on.’”), but Jaryk is reluctant to revisit the past.

When he finally makes it to India, it is not because he’s agreed to help stage the play but only because Misha has died, and he needs to collect his remains. But at some point during his visit, the poor people of Gopalpur “become his poor people, a month here just long enough for loyalty to grow in him like a desert plant.” Exactly how this happened, despite what must have been a pretty serious language barrier, is never really explained, let alone dramatized. Meanwhile, he doesn’t call Lucy—setting off yet another painful chain of events—because he “could not bring himself . . . to ask her to interrupt her life for him.” This might make sense, except that he left her a letter before he departed for India, asking her to come and, um, disrupt her life for him.

And it’s not only Jaryk whose actions often seem dictated by the constraints of an overengineered plot. Midway through the novel, after Jaryk has already left for India, Lucy discovers she’s pregnant with his child. Despite her feelings of abandonment and the advice of her obstetrician, Lucy travels to India, spending what must have been an exceedingly large percentage of her employment office salary on the ticket. Why? Well, because “she wanted to tell Jaryk the news herself. She wanted to tell him in person, not over the phone and not by letter.”

And so on and so forth. What passes for internal motivations in Chakrabarti’s narrative are mostly just restatements of the character’s actions: I didn’t call because I couldn’t bear to call. I came because I couldn’t not come. I stayed because, having come, I had to stay.

If the Warsaw Ghetto and New York portions of the novel display a tendency to selective readings of history, it is nothing compared to what happens when we get to India. Take what the professor tells Misha and Jaryk of the political situation: “The problem is that in my home state young men are disappearing. The problem is that police are shooting at protestors at public rallies. I can’t tell you how many students I’ve taught who’ve ended up in jail, or worse.” We get slightly (slightly!) more from Misha, who has done his own research on the matter:

They were taking youths from the city, lads who’d rather be studying economics or writing poetry, or the ones they’d corralled from the villages, who had no money to their name, who fashioned bows and arrows from the wood of their ancestral trees. The problem was familiar: they wanted to live in a world where everyone—even the refugees from Bangladesh—had their share of workable land, but wealth belonged to the old guard.

This is, to put it lightly, a naive account of the militant Maoist movements that waged guerrilla warfare across India, targeting “class enemies” such as landlords, politicians, businesspeople, and police. Although, no doubt, some members of the Naxalite insurgency were would-be poets and economists who fashioned bows and arrows from ancestral trees, Misha’s description is consistent with the pervading sentimentality of Chakrabarti’s novel, which turns on the tragedy of the Warsaw Ghetto while eliding its harshest realities.

If there is an ethic hidden beneath the boundless, often blinding sentimentalities of A Play for the End of the World, it is articulated by Lucy, who, upon boarding a Midtown Manhattan subway car, reflects fleetingly on the chaos and suffering of the world around her:

Scattered on the platform lies the New York Daily News with articles of robberies and acts of violence so seemingly mindless that she can’t believe the printed word. This is her chosen city, where entering a subway car, she feels she must keep her eyes to herself, though she won’t—she doesn’t have it in her to ignore the people with whom she shares space—glancing up to see a businessman, a teenager immersed in his comic book, and a woman without shoes, her bare feet scratching the floor of the car, exposing the cracks. This is the city she has chosen, and she will not look away.

Lucy understands that there is a kind of trade-off in choosing to dwell in a place where tenderness and beauty mingle with degradation and poverty—she must take it all in, even the hardest, most painful facts.

It’s a pity for the novel, in the end, that Chakrabarti couldn’t do the same.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Killer Backdrop

If Auschwitz can have a gift shop, why can’t the Warsaw Ghetto have a love story?

Unquiet Ghosts of the Ghetto

As we mark the 80th anniversary of the fall of Poland to the Germans in World War II, a new documentary gives a glimpse inside the Warsaw Ghetto.

These Heroic Girls

On Christmas Eve, 1941, three young Jewish women spent the evening in the company of Nazis, secretly gathering intelligence on behalf of the underground Jewish resistance.

Du Bois, the Warsaw Ghetto, and a Priestly Blessing

When the editors at Jewish Life asked the venerable civil rights leader W. E. B. Du Bois to speak about the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, they had no idea that it would lead to a priestly blessing.

David L. Spraragen

Mr. Leibowitz: As we say, "kol ha-kavod." Your review of Jai Chakrabarti’s "A Play for the End of the World" could not have been a pleasant task. Unlike many uncritical and superficial book reviews, yours honorably holds this debut novel to the lofty standard that its most sacred subject demands. I visited the Janusz Korczak Association/Beit Lohamei HaGhetaot in Haifa and treasure every chapter of their comprehensive three volume Hebrew set, "Studies in the Heritage of Janusz Korczak." By panning this no doubt well-intended, but seriously flawed attempt at historical fiction you have also demonstrated that any account of the heart wrenching and inspiring story of Korczak must be undertaken with the greatest of care, research and respect.